Determining the Extent of the Work for Hire Doctrine and Its Effect on Termination Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

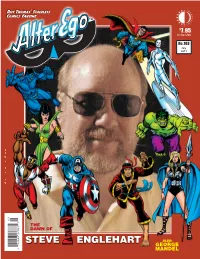

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

By JOHN WELLS a M E R I C a N C H R O N I C L E S

AMERICAN CHRONICLES THE 1965-1969 by JOHN WELLS Table of Contents Introductory Note about the Chronological Structure of American Comic Book Chronicles ................. 4 Note on Comic Book Sales and Circulation Data.......................................... 5 Introduction & Acknowledgements ............ 6 Chapter One: 1965 Perception................................................................8 Chapter Two: 1966 Caped.Crusaders,.Masked.Invaders.............. 69 Chapter Three: 1967 After.The.Gold.Rush.........................................146 Chapter Four: 1968 A.Hazy.Shade.of.Winter.................................190 Chapter Five: 1969 Bad.Moon.Rising..............................................232 Works Cited ...................................................... 276 Index .................................................................. 285 Perception Comics, the March 18, 1965, edition of Newsweek declared, were “no laughing matter.” However trite the headline may have been even then, it wasn’t really wrong. In the span of five years, the balance of power in the comic book field had changed dramatically. Industry leader Dell had fallen out of favor thanks to a 1962 split with client Western Publications that resulted in the latter producing comics for themselves—much of it licensed properties—as the widely-respected Gold Key Comics. The stuffily-named National Periodical Publications—later better known as DC Comics—had seized the number one spot for itself al- though its flagship Superman title could only claim the honor of -

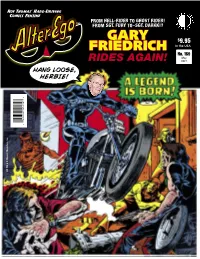

Gary Friedrich

Roy Thomas' Hard-Driving Comics Fanzine FROM HELL-RIDER TO GHOST RIDER! FROM SGT. FURY TO–SGT. DARKK!? GARY $9.95 FRIEDRICH In the USA No. 169 May RIDES AGAIN! 2021 HANG LOOSE, HERBIE! 7 4 3 4 0 0 8 5 6 2 8 1 Art TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 169 / May 2021 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editor Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Don’t STEAL our J.T. Go (Assoc. Editor) Digital Editions! Comic Crypt Editor C’mon citizen, DO THE RIGHT Michael T. Gilbert THING! A Mom & Pop publisher Editorial Honor Roll like us needs every sale just to Jerry G. Bails (founder) survive! DON’T DOWNLOAD Ronn Foss, Biljo White OR READ ILLEGAL COPIES ONLINE! Mike Friedrich, Bill Schelly Buy affordable, legal downloads only at www.twomorrows.com Proofreaders or through our Apple and Google Apps! Rob Smentek William J. Dowlding & DON’T SHARE THEM WITH FRIENDS OR POST THEM ONLINE. Help us keep Cover Artist producing great publications like this one! Mike Ploog Cover Colorist Unknown With Special Thanks to: Heidi Amash Beverly Hahs Contents Richard J. Arndt Kirk Hastings Bob Bailey Robert Higgerson Writer/Editorial: My Best Friend—Gary Friedrich .......... 2 Carol Bierschwal Sean Howe “Gary Friedrich And I Were Part Of Each Other’s Lives Danny Bierschwal Jim Kealy Ray Bottorff, Jr. Troy R. Kinunen For Over 60 Years” ................................. 3 Len Brown Katy Kirn A conversation with Roy Thomas about those six decades, conducted by Richard Arndt. Jean Caccicedo Tyler M. -

Marvelcomicsinthe70spreview.Pdf

Contents Introduction: The Twilight Years . 5 PART I: 1968-1970 . 9 PART II: 1970-1974 . 46 PART III: 1974-1976 . 155 PART IV: 1976-1979 . 203 Creator Spotlights : Roy Thomas . 10 Gene Colan . 16 Neal Adams . 31 Gil Kane . 52 Joe Sinnott . 54 Gerry Conway . 90 Marv Wolfman . 143 Jim Starlin . 150 Jim Shooter . 197 John Byrne . 210 Frank Miller . 218 Key Marvel Moments : Marvel Con . 175 Marvel Comics in the 1970s 3 Introduction: The Twilight Years n volume one, Marvel Comics in the 1960s , it was mix, vaulting Marvel Comics into a pop-culture Ishown how the development of the company’s new movement that threatened to overwhelm established line of super-hero books introduced in that decade notions of art and its role in society. As a result, Lee could be broken up into four distinct phases: the came to be seen as Marvel’s front man, and through a Formative Years, the Years of Consolidation, the combination of speech making, magazine interviews, Grandiose Years, and the Twilight Years. Led by and his often inspiring comic book scripts, he became editor Stan Lee, who was allied with some of the a sort of pop guru to many of his youthful readers. best artists in the business including Jack Kirby, However, by 1968, Marvel Comics had reached its Steve Ditko, Don Heck, John Romita, John Buscema, zenith in terms of its development and sheer creative Jim Steranko, and Gene Colan, Marvel moved quickly power. Soon after came an expansion of the company’s from its early years when concepts involving continuity line of titles and a commensurate dilution of the and characterization were intro - duced to new features with little thought given to their revolu - tionary impact on the industry to the Years of Consolidation when concepts of characteriza - tion, continuity, and realism began to be actively applied. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

$ 8 . 9 5 Dr. Strange and Clea TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.71 Apri l 2014 0 3 1 82658 27762 8 Marvel Premiere Marvel • Premiere Marvel Spotlight • Showcase • 1st Issue Special Showcase • & New more! Talent TRYOUTS, ONE-SHOTS, & ONE-HIT WONDERS! Featuring BRUNNER • COLAN • ENGLEHART • PLOOG • TRIMPE COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND COMICS’ BRONZE AGE BEYOND! Volume 1, Number 71 April 2014 Celebrating the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Arthur Adams (art from the collection of David Mandel) COVER COLORIST ONE-HIT WONDERS: The Bat-Squad . .2 Glenn Whitmore Batman’s small band of British helpers were seen in a single Brave and Bold issue COVER DESIGNER ONE-HIT WONDERS: The Crusader . .4 Michael Kronenberg Hopefully you didn’t grow too attached to the guest hero in Aquaman #56 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: Ready for the Marvel Spotlight . .6 Creators galore look back at the series that launched several important concepts SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz David Kirkpatrick FLASHBACK: Marvel Feature . .14 Arthur Adams Todd Klein Mark Arnold David Anthony Kraft Home to the Defenders, Ant-Man, and Thing team-ups Michael Aushenker Paul Kupperberg Frank Balas Paul Levitz FLASHBACK: Marvel Premiere . .19 Chris Brennaman Steve Lightle A round-up of familiar, freaky, and failed features, with numerous creator anecdotes Norm Breyfogle Dave Lillard Eliot R. Brown David Mandel FLASHBACK: Strange Tales . .33 Cary Burkett Kelvin Mao Jarrod Buttery Marvel Comics The disposable heroes and throwaway characters of Marvel’s weirdest tryout book Nick Cardy David Michelinie Dewey Cassell Allen Milgrom BEYOND CAPES: 221B at DC: Sherlock Holmes at DC Comics . -

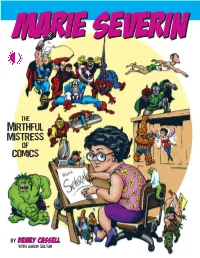

Marie Severinseverin

MarieMarie SeverinSeverin THE MiRTHful MisTREss Of COMiCs bY DEwEy CAssEll WiTH AAROn sulTAn FOREWORD INTRODUCTION .............................. HOME ............................................. Family .............................................................4 ............................................................. Interview with Marie Interview with John Severin 5 Friends ................................ 7 ......................................................... Interview with Marie 7 78 ..................... 7 .............. 80 .............................. 9 80 12 Interview with Jim Mooney 81 12 .................................................... ......................... The Cat .................. 83 nterviewI with Jean Davenport Interview with Marie Interview with Eleanor Hezel Interview with Linda Fite HORROR 83 ................................................................ EC ................................................ Kull 87 ........................................................... ......... REH: Lone Star ............................................ Fictioneer Interview ................... with Interview with Marie ............ 13 87 John Severin Interview with Al Feldstein 17 87 Other Characters ............................................ and Comics I 23 87 nterview with Jack Davis .................... Spider-Man 23 ............................................... Interview with Jack Kamen on Man 88 ............23 Ir ...................................... “The Artists of EC comics” ............... izard -

Marvel Comics Marvel Comics

Roy Tho mas ’Marvel of a ’ $ Comics Fan zine A 1970s BULLPENNER In8 th.e9 U5SA TALKS ABOUT No.108 MARVELL CCOOMMIICCSS April & SSOOMMEE CCOOMMIICC BBOOOOKK LLEEGGEENNDDSS 2012 WARREN REECE ON CLOSE EENNCCOOUUNNTTEERRSS WWIITTHH:: BIILL EVERETT CARL BURGOS STAN LEE JOHN ROMIITA MARIIE SEVERIIN NEAL ADAMS GARY FRIIEDRIICH ALAN KUPPERBERG ROY THOMAS AND OTHERS!! PLUS:: GOLDEN AGE ARTIIST MIKE PEPPE AND MORE!! 4 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 6 2 8 1 Art ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc.; Human Torch & Sub-Mariner logos ™ Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 108 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) AT LAST! Ronn Foss, Biljo White LL IN Mike Friedrich A Proofreader COLOR FOR Rob Smentek .95! Cover Artists $8 Carl Burgos & Bill Everett Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Writer/Editorial: Magnificent Obsession . 2 “With The Fathers Of Our Heroes” . 3 Glenn Ald Barbara Harmon Roy Ald Heritage Comics 1970s Marvel Bullpenner Warren Reece talks about legends Bill Everett & Carl Burgos— Heidi Amash Archives and how he amassed an incomparable collection of early Timelys. Michael Ambrose Roger Hill “I’m Responsible For What I’ve Done” . 35 Dave Armstrong Douglas Jones (“Gaff”) Part III of Jim Amash’s candid conversation with artist Tony Tallarico—re Charlton, this time! Richard Arndt David Karlen [blog] “Being A Cartoonist Didn’t Really Define Him” . 47 Bob Bailey David Anthony Kraft John Benson Alan Kupperberg Dewey Cassell talks with Fern Peppe about her husband, Golden/Silver Age inker Mike Peppe. -

Newfangles 37 1970-07

NEWFANGLES 37 from Don & Jfeggie Thompson, 8786 Hendricks Rd., Mentor, Ohio 44060. 100 a copy- through #40, 200 there after (see inside for an explanation). Back issues (24 29 30 33 35) @100. Our circulation is 437, up 100 from last month, almost entirely due to mention in RBCC. Our title logo this month is by Jim Warren, who is a good man. The Dick Tracy cartoon inside somewhere is bv Mike Britt. 373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737373737 2000/ attend NY Comicon. That was paid attendance as of the first day; most estimates run considerably higher. There were some complaints (traders all over the halls, blocking traffic; hotel goons challenging anyone not wearing convention identification — one goon, really overly officious, challenged Guest of Honor Bill Everett even though Everett was standing by a huge photo of himself at the time) but most seemed to think it was a good convention. We only have a handful of reports so far. Sol Brodsky has quit Marvel to form his own publishing firm (not comics). John Verpoorten is replacing him as Marvel’s production manager. Gary Friedrich has quit Marvel, too, again. He did the first part of a Daredevil 2-parter based on the Chicago 7, quit without notice between installments. Challengers of the Unknown dies with #77, though one report said the Deadman issue did so well the book might be renewed with Deadman on a more-or-less-regular basis. Silver Surfer died with 18, the Kirby issue; Trimpe did the first page, was working on the second for his first issue when the book was killed. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

Justice League of America TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. December 2013 No.69 $ 9 . 9 5 100-PAGE TENTH EDITION ANNIVERSARY 100-PAGE 1 1 1 82658 27762 8 Volume 1, 1994--2013 Number 69 December 2013 Celebrating the Best Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Dan Jurgens and Ray McCarthy COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER FLASHBACK: A Slow Start for Anniversary Editions . .2 Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER FLASHBACK: The House of Ideas’ Herculean 100th Issues!! . .4 Rob Smentek BEYOND CAPES: The “Antiversary” Issue . .14 SPECIAL THANKS FLASHBACK: Adventure Comics #400: Really? . .22 Jack Abramowitz Elliot S. Maggin Frankie Addiego Andy Mangels FLASHBACK: The Brave and the Bold #100, 150, and 200 . .25 David T. Allen Franck Martini Mark Arnold David Michelinie FLASHBACK: Superman #300 . .31 Mike W. Barr Mark Millar Cary Bates Doug Moench OFF MY CHEST: The Siegel/Superman lawsuit by Larry Tye, excerpted from his book, Jerry Boyd Pamela Mullin Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero . .34 KC Carlson Mike Pigott Gerry Conway Charlie Roberts FLASHBACK: Showcase #100 . .38 DC Comics John Romita, Sr. BEYOND CAPES: Casper #200 and Richie Rich #200 . .41 Daniel DeAngelo Steve Rude Tom DeFalco Michael Savene INTERVIEW: Marv Wolfman on Fantastic Four #200 and Amazing Spider-Man #200 . .44 Steve Englehart Alex Segura A.J. Fowlks Marie Severin FLASHBACK: Batman #300 and 400 . .49 Grand Comic-Book Craig Shutt Database Walter Simonson BACKSTAGE PASS: Bob Greenberger’s Memories of Detective Comics #500 . -

ATLAS COMICS / INDEX — Tristan Lapoussière —

ATLAS COMICS / INDEX — Tristan Lapoussière — Pour plus de facilité, la production Seaboard / Atlas a été divisée ici en deux grandes catégories, les comic- books couleurs et les magazines noir et blanc. Nous avons ajouté une troisième catégorie, celle des titres an- noncés mais qui n'ont jamais paru ; la liste en a été dressée en compulsant les colonnes éditoriales rédigées par Larry Lieber, les annonces faites dans les pages de courrier, et les annonces en dernière page du dernier numéro de certaines séries. Cet index est le plus complet jamais paru ; il corrige certaines erreurs ou imprécisions commises dans les bi- bliographies précédentes, et comprend les publications omises dans l'ouvrage Tous les comics Atlas. Ordre des crédits : dessinateur, encreur, scénariste. Abréviations : [c] couverture ; [pc] couverture peinte ; [nt] histoire non titrée ; FR: parution en France. A/ COMIC-BOOKS The Barbarians 1 (06/75) [c] Iron Jaw Rich Buckler Jack Abel Iron Jaw The Mountain of Mutants Pablo Marcos Pablo Marcos Gary Friedrich 10p Andrax [nt] Jordi Bernet Jordi Bernet Miquel Cussó 9p FR: album Andrax [Ed. Peplum, 1990 ; par le biais de la réédition espagnole publiée chez Toutain] 27 Blazing Battle Tales 1 (07/75) [c] Sgt Hawk Frank Thorne Frank Thorne Sgt Hawk The One-Armed Beast Pat Broderick Jack Sparling John Albano 12p [NB: le personnage du Sgt Hawk devait au départ s'appeler Sgt Stone] The Sky Demon Al McWilliams Al McWilliams John Albano 6p BBT Salutes Bronze Star Winner Pvt William Swanson John Severin John Severin John Albano 2p The Brute 1 (02/75) [c] The Brute Dick Giordano Dick Giordano The Brute Night of the Brute Mike Sekowsky Pablo Marcos Mike Fleisher 20p The Brute 2 (04/75) [c] The Brute Dick Giordano Dick Giordano The Brute Attack of the Reptile-Man Mike Sekowsky Pablo Marcos Mike Fleisher 20p The Brute 3 (07/75) [c] The Brute Pablo Marcos Pablo Marcos The Brute Live Or Let Die Alan Weiss Jack Abel Gary Friedrich 20p The Cougar 1 (04/75) [c] The Cougar Frank Thorne Frank Thorne The Cougar Vampires and Cougars Don't Mix Dan Adkins & F.