Marvelcomicsinthe70spreview.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Oktober 1968 CM # 005 (20 Seiten) Autor: Arnold Drake, Zeichner: Don Heck, Inker: John Tartaglione Hit Comics Nr. 203 , 1970 Rä

CAPTAIN MARVEL Checkliste (klassische Deutsche Ausgaben 1967-1977) Marvel Super-Heroes (Vol. 1) # 12-13 Oktober 1968 (Dezember 1967 - März 1968) CM # 005“The Mark Of The Metazoid!” (20 Seiten) Captain Marvel (Vol. 1) # 1-14 Autor: Arnold Drake, Zeichner: Don Heck, (Mai 1968 - Juli 1969) Inker: John Tartaglione Hit Comics Nr. 203 Dezember 1967 „Der Angriff des Metazoids“, 1970 MSH # 12“The Coming Of Captain Marvel!” (15 Seiten) Autor: Stan Lee, Zeichner: Gene Colan, Inker: Frank Giacoia Rächer Nr. 12-15„Das Los des Metazoiden!“ , (keine deutsche Veröffentlichung) Dezember 1974-März 1975 Übersetzung: Hartmut Huff, März 1968 Lettering: C. Raschke/U. Mordek/ MSH # 13“Where Stalks The Sentry!” (20 Seiten) M. Gerson/U. Mordek Autor: Roy Thomas, Zeichner: Gene Colan, Inker: Paul Reinman November 1968 (keine deutsche Veröffentlichung) CM # 006“In The Path Of Solam!” (20 Seiten) Autor: Arnold Drake, Zeichner: Don Heck, Mai 1968 Inker: John Tartaglione CM # 001“Out Of The Holocaust - - A Hero!” (21 Seiten) Hit Comics Nr. 203 Autor: Roy Thomas, Zeichner: Gene Colan, „Die Macht des Solams“, 1970 Inker: Vince Colletta Hit Comics Nr. 121 Rächer Nr. 16-18„Auf Solams Spur!“ , „Ein Sieger ohnegleichen“, 1969 April-Juni 1975 Übersetzung: Hartmut Huff, Rächer Nr. 1-3„Der Kampf der Titanen!“ , Lettering: Marlies Gerson, Januar-März 1974 Ursula Mordek (Rächer 16) Lettering: Ursula Mordek (nur Seite 1-7) (Originalseite 15 fehlt) Juli 1968 CM # 002 “From The Void Of Space Comes-- The Super Skrull!” (20 Seiten) Autor: Roy Thomas, Zeichner: Gene Colan, Inker: Vince Colletta Hit Comics Nr. 121 „Der Angriff des Super-Skrull“, 1969 Rächer Nr. -

Representing Heroes, Villains and Anti- Heroes in Comics and Graphic

H-Film CFP: Who’s Bad? Representing Heroes, Villains and Anti- Heroes in Comics and Graphic Narratives – A seminar sponsored by the ICLA Research Committee on Comic Studies and Graphic Narratives Discussion published by Angelo Piepoli on Wednesday, September 7, 2016 This is a Call for Papers for a proposed seminar to be held as part of the American Comparative Literature Association's 2017 Annual Meeting. It will take place at Utrecht University in Utrecht, the Netherlands on July 6-9, 2017. Submitters are required to get a free account on the ACLA's website at http://www.acla.org/user/register . Abstracts are limited to 1500 characters, including spaces. If you wish to submit an astract, visit http://www.acla.org/node/12223 . The deadline for paper submission is September 23, 2016. Since the publication of La vida de Lazarillo de Tormes y de sus fortuna y adversidades in 1554, the figure of the anti-hero, which had originated in Homeric literature, has had great literary fortune over the centuries. Satan as the personification of evil, then, was the most interesting character in Paradise Lost by John Milton and initiated a long series of fascinating literary villains. It is interesting to notice that, in a large part of the narratives of these troubled times we are living in, the protagonist of the story is everything but a hero and the most acclaimed characters cross the moral borders quite frequently. This is a fairly common phenomenon in literature as much as in comics and graphic narratives. The advent of the Modern Age of Comic Books in the U.S. -

Captain Marvel: Earths Mightiest Hero Vol

CAPTAIN MARVEL: EARTHS MIGHTIEST HERO VOL. 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kelly Sue Deconnick | 264 pages | 28 Jun 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9781302901271 | English | New York, United States Captain Marvel: Earths Mightiest Hero Vol. 1 PDF Book But when you are expecting a 5-star-knock-it-out-of-the-park story, it can be a bit of a letdown. May 07, Rebeckah Sypik rated it really liked it. Can they resolve it before a threat from the ocean depths attacks? And it looks like she has the world's worst wedgie. This is business as usual for modern comic book omnibuses. As iconic heroes enjoyed worldwide cinematic success, a diverse array of young champions stole the spotlight! And can both Captain Marvels stop it before they get shipwrecked? Other Editions 1. See all my reviews and more at www. About Kelly Sue DeConnick. Carol goes through some adversity finding she has lesions on her brain, and she can't exert herself therefore she has been 'grounded' There are some decent clashes and action, but overall not as strong as this volume opened up. His early life is largely unknown, but he became a xenobiologist and Pluskommander of the Kree Void Science Navy. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Continental USA only. Pretty excited to read what comes next. Other editions. As Dr. See details. Report item - opens in a new window or tab. You'd have made Thelma and Louise look like the Andrews sisters. As part of a S. Please wait for a combined invoice to pay from. -

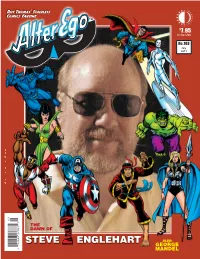

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

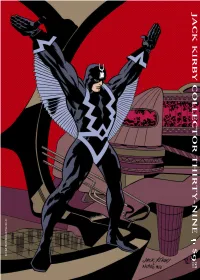

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR THIRTY-NINE $9 95 IN THE US . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M 3 0 0 2 © & M T t l o B k c a l B FAN FAVORITES! THE NEW COPYRIGHTS: Angry Charlie, Batman, Ben Boxer, Big Barda, Darkseid, Dr. Fate, Green Lantern, RETROSPECTIVE . .68 Guardian, Joker, Justice League of America, Kalibak, Kamandi, Lightray, Losers, Manhunter, (the real Silver Surfer—Jack’s, that is) New Gods, Newsboy Legion, OMAC, Orion, Super Powers, Superman, True Divorce, Wonder Woman COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .78 TM & ©2003 DC Comics • 2001 characters, (some very artful letters on #37-38) Ardina, Blastaar, Bucky, Captain America, Dr. Doom, Fantastic Four (Mr. Fantastic, Human #39, FALL 2003 Collector PARTING SHOT . .80 Torch, Thing, Invisible Girl), Frightful Four (Medusa, Wizard, Sandman, Trapster), Galactus, (we’ve got a Thing for you) Gargoyle, hercules, Hulk, Ikaris, Inhumans (Black OPENING SHOT . .2 KIRBY OBSCURA . .21 Bolt, Crystal, Lockjaw, Gorgon, Medusa, Karnak, C Front cover inks: MIKE ALLRED (where the editor lists his favorite things) (Barry Forshaw has more rare Kirby stuff) Triton, Maximus), Iron Man, Leader, Loki, Machine Front cover colors: LAURA ALLRED Man, Nick Fury, Rawhide Kid, Rick Jones, o Sentinels, Sgt. Fury, Shalla Bal, Silver Surfer, Sub- UNDER THE COVERS . .3 GALLERY (GUEST EDITED!) . .22 Back cover inks: P. CRAIG RUSSELL Mariner, Thor, Two-Gun Kid, Tyrannus, Watcher, (Jerry Boyd asks nearly everyone what (congrats Chris Beneke!) Back cover colors: TOM ZIUKO Wyatt Wingfoot, X-Men (Angel, Cyclops, Beast, n their fave Kirby cover is) Iceman, Marvel Girl) TM & ©2003 Marvel Photocopies of Jack’s uninked pencils from Characters, Inc. -

Doctor Strange Epic Collection: a Separate Reality Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DOCTOR STRANGE EPIC COLLECTION: A SEPARATE REALITY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Steve Englehart,Roy Thomas,Gardner F. Fox | 472 pages | 08 Nov 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785194446 | English | New York, United States Doctor Strange Epic Collection: A Separate Reality PDF Book All rights to cover images reserved by the respective copyright holders. Use your keyboard! The art is right up my alley; '70s psychedelia is among my favorite things. The treatment of Wong made me cringe a few too many times to really enjoy it, but I am delighted at the idea that the Vatican has a copy of the Necronomicon. This will not affect the original upload Small Medium How do you want the image positioned around text? Recent searches Clear All. Table of Contents: 29 Dr. You must be logged in to write a review for this comic. Sort order. Table of Contents: 39 Dr. Howard's Unaussprechlichen Kulten and excellent psycedelic artwork. Sorry, but we can't respond to individual comments. Gorgeous art! Not so great is exactly what you'd expect: the corny plotting and dialogue that goes hand in hand in comic works from the 70's. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. May 13, Laura rated it liked it Shelves: cthulhu , death , fanfiction , graphic-novel , gygaxy , necromancy , nyarlothotep. Marvel , Series. What size image should we insert? Still wonderful to visit. Here at Walmart. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. The Return! Oct 14, Tony Romine rated it it was amazing. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Banner is sent to another dimension where he turns into the Hulk and faces the Night-Crawler. -

Simonson's Thor Bronze Age Thor New Gods • Eternals

201 1 December .53 No 5 SIMONSON’S THOR $ 8 . 9 BRONZE AGE THOR NEW GODS • ETERNALS “PRO2PRO” interview with DeFALCO & FRENZ HERCULES • MOONDRAGON exclusive MOORCOCK interview! 1 1 1 82658 27762 8 Volume 1, Number 53 December 2011 Celebrating The Retro Comics Experience! the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks . COVER ARTIST c n I , s Walter Simonson r e t c a r a COVER COLORIST h C l Glenn Whitmore e v r a BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 M COVER DESIGNERS 1 1 0 2 Michael Kronenberg and John Morrow FLASHBACK: The Old Order Changeth! Thor in the Early Bronze Age . .3 © . Stan Lee, Roy Thomas, and Gerry Conway remember their time in Asgard s n o i PROOFREADER t c u OFF MY CHEST: Three Ways to End the New Gods Saga . .11 A Rob Smentek s c The Eternals, Captain Victory, and Hunger Dogs—how Jack Kirby’s gods continued with i m SPECIAL THANKS o C and without the King e g Jack Abramowitz Brian K. Morris a t i r FLASHBACK: Moondragon: Goddess in Her Own Mind . .19 e Matt Adler Luigi Novi H f Getting inside the head of this Avenger/Defender o Roger Ash Alan J. Porter y s e t Bob Budiansky Jason Shayer r FLASHBACK: The Tapestry of Walter Simonson’s Thor . .25 u o C Sal Buscema Walter Simonson Nearly 30 years later, we’re still talking about Simonson’s Thor —and the visionary and . -

Katalog Zur Ausstellung "60 Jahre Marvel

Liebe Kulturfreund*innen, bereits seit Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs befasst sich das Amerikahaus München mit US- amerikanischer Kultur. Als US-amerikanische Behörde war es zunächst für seine Bibliothek und seinen Lesesaal bekannt. Doch schon bald wurde das Programm des Amerikahauses durch Konzerte, Filmvorführungen und Vorträge ergänzt. Im Jahr 1957 zog das Amerika- haus in sein heutiges charakteristisches Gebäude ein und ist dort, nach einer vierjährigen Generalsanierung, seit letztem Jahr wieder zu finden. 2014 gründete sich die Stiftung Bay- erisches Amerikahaus, deren Träger der Freistaat Bayern ist. Heute bietet das Amerikahaus der Münchner Gesellschaft und über die Stadt- und Landesgrenzen hinaus ein vielfältiges Programm zu Themen rund um die transatlantischen Beziehungen – die Vereinigten Staaten, Kanada und Lateinamerika- und dem Schwerpunkt Demokratie an. Unsere einladenden Aus- stellungräume geben uns die Möglichkeit, Werke herausragender Künstler*innen zu zeigen. Mit dem Comicfestival München verbindet das Amerikahaus eine langjährige Partnerschaft. Wir freuen uns sehr, dass wir mit der Ausstellung „60 Jahre Marvel Comics Universe“ bereits die fünfte Ausstellung im Rahmen des Comicfestivals bei uns im Haus zeigen können. In der Vergangenheit haben wir mit unseren Ausstellungen einzelne Comickünstler, wie Tom Bunk, Robert Crumb oder Denis Kitchen gewürdigt. Vor zwei Jahren freute sich unser Publikum über die Ausstellung „80 Jahre Batman“. Dieses Jahr schließen wir mit einem weiteren Jubiläum an und feiern das 60-jährige Bestehen des Marvel-Verlags. Im Mainstream sind die Marvel- Helden durch die in den letzten Jahren immer beliebter gewordenen Blockbuster bekannt geworden, doch Spider-Man & Co. gab es schon lange davor. Das Comic-Heft „Fantastic Four #1“ gab vor 60 Jahren den Startschuss des legendären Marvel-Universums. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

Cons & Confusion

Cons & Confusion The almost accurate convention listing of the B.T.C.! We try to list every WHO event, and any SF event near Buffalo. updated: June 23, 2021 to add an SF/DW/Trek/Anime/etc. event; send information to: [email protected] PLEASE DOUBLECHECK ALL EVENTS, THINGS ARE STILL BE POSTPONED OR CANCELLED. SOMETIMES FACEBOOK WILL SAY CANCELLED YET WEBSITE STILL SHOWS REGULAR EVENT! JUNE 24 NYC BIG APPLE COMIC CON-Summer Event New Yorker Htl, Manhatten, NY NY www.bigapplecc.com JUNE 25 Virt ANIME: NAUSICAA OF THE VALLEY OF THE WIND group watch event (requires Netflix account) https://www.fanexpocanada.com JUNE 25 Virt STAR WARS TRIVIA: ROGUE ONE round one features Rogue One movie trivia game https://www.fanexpocanada.com JUNE 25-27 S.F. CREATION - SUPERNATURAL Hyatt Regency Htl, San Francisco CA TV series tribute https://www.creationent.com/ JUNE 26-27 N.J. CREATION - STRANGER THINGS NJ Conv Ctr, Edison, NJ (NYC) TV series tribute https://www.creationent.com/ JUNE 27 Virt WIZARD WORLD-STAR TREK GUEST STARS Virtual event w/ cast some parts free, else to buy https://wizardworld.com/ Charlie Brill, Jeremey Roberts, John Rubenstein, Gary Frank, Diane Salinger, Kevin Brief JUNE 27 BTC BUFFALO TIME COUNCIL MEETING 49 Greenwood Pl, Buffalo monthly BTC meeting buffalotime council.org YES!! WE WILL HAVE A MEETING! JULY 8-11 MA READERCON Marriott Htl, Quincy, Mass (Boston) Books & Authors http://readercon.org/ Jeffrey Ford, Ursula Vernon, Vonda N McIntyre (in Memorial) JULY 9-11 T.O. TFCON DELAYED UNTIL DEC 10-12, 2021 Transformers fan-run