European Journal of American Studies, 10-2 | 2015 the Mutant Problem: X-Men, Confirmation Bias, and the Methodology of Comics A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust

W E SPOKE OUT COMIC BOOKS W E SPOKE OUT COMIC BOOKS AND THE HOLOCAUST AND NEAL ADAMS RAFAEL MEDOFF CRAIG YOE INTRODUCTION AND THE HOLOCAUST AFTERWORD BY STAN LEE NEAL ADAMS MEDOFF RAFAEL CRAIG YOE LEE STAN “RIVETING!” —Prof. Walter Reich, Former Director, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Long before the Holocaust was widely taught in schools or dramatized in films such asSchindler’s List, America’s youth was learning about the Nazi genocide from Batman, X-Men, and Captain America. Join iconic artist Neal Adams, the legend- ary Stan Lee, Holocaust scholar Dr. Rafael Medoff, and Eisner-winning comics historian Craig Yoe as they take you on an extraordinary journey in We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust. We Spoke Out showcases classic comic book stories about the Holocaust and includes commentaries by some of their pres- tigious creators. Writers whose work is featured include Chris Claremont, Archie Goodwin, Al Feldstein, Robert Kanigher, Harvey Kurtzman, and Roy Thomas. Along with Neal Adams (who also drew the cover of this remarkable volume), artists in- clude Gene Colan, Jack Davis, Carmine Infantino, Gil Kane, Bernie Krigstein, Frank Miller, John Severin, and Wally Wood. In We Spoke Out, you’ll see how these amazing comics creators helped introduce an entire generation to a compelling and important subject—a topic as relevant today as ever. ® Visit ISBN: 978-1-63140-888-5 YoeBooks.com idwpublishing.com $49.99 US/ $65.99 CAN ® ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors are grateful to friends and colleagues who assisted with various aspects of this project: Kris Stone and Peter Stone, of Continuity Studios; Gregory Pan, of Marvel Comics; Thomas Wood, Jay Kogan, and Mandy Noack-Barr, of DC Comics; Dan Braun, of New Comic Company (Warren Publications); Corey Mifsud, Cathy Gaines-Mifsud, and Dorothy Crouch of EC Comics; Robert Carter, Jon Gotthold, Michelle Nolan, Thomas Martin, Steve Fears, Rich Arndt, Kevin Reddy, Steve Bergson, and Jeff Reid, who provided information or scans; Jon B. -

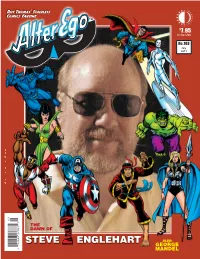

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

Tsr6903.Mu7.Ghotmu.C

[ Official Game Accessory Gamer's Handbook of the Volume 7 Contents Arcanna ................................3 Puck .............. ....................69 Cable ........... .... ....................5 Quantum ...............................71 Calypso .................................7 Rage ..................................73 Crimson and the Raven . ..................9 Red Wolf ...............................75 Crossbones ............................ 11 Rintrah .............. ..................77 Dane, Lorna ............. ...............13 Sefton, Amanda .........................79 Doctor Spectrum ........................15 Sersi ..................................81 Force ................................. 17 Set ................. ...................83 Gambit ................................21 Shadowmasters .... ... ..................85 Ghost Rider ............................23 Sif .................. ..................87 Great Lakes Avengers ....... .............25 Skinhead ...............................89 Guardians of the Galaxy . .................27 Solo ...................................91 Hodge, Cameron ........................33 Spider-Slayers .......... ................93 Kaluu ....... ............. ..............35 Stellaris ................................99 Kid Nova ................... ............37 Stygorr ...............................10 1 Knight and Fogg .........................39 Styx and Stone .........................10 3 Madame Web ...........................41 Sundragon ................... .........10 5 Marvel Boy .............................43 -

Aliens of Marvel Universe

Index DEM's Foreword: 2 GUNA 42 RIGELLIANS 26 AJM’s Foreword: 2 HERMS 42 R'MALK'I 26 TO THE STARS: 4 HIBERS 16 ROCLITES 26 Building a Starship: 5 HORUSIANS 17 R'ZAHNIANS 27 The Milky Way Galaxy: 8 HUJAH 17 SAGITTARIANS 27 The Races of the Milky Way: 9 INTERDITES 17 SARKS 27 The Andromeda Galaxy: 35 JUDANS 17 Saurids 47 Races of the Skrull Empire: 36 KALLUSIANS 39 sidri 47 Races Opposing the Skrulls: 39 KAMADO 18 SIRIANS 27 Neutral/Noncombatant Races: 41 KAWA 42 SIRIS 28 Races from Other Galaxies 45 KLKLX 18 SIRUSITES 28 Reference points on the net 50 KODABAKS 18 SKRULLS 36 AAKON 9 Korbinites 45 SLIGS 28 A'ASKAVARII 9 KOSMOSIANS 18 S'MGGANI 28 ACHERNONIANS 9 KRONANS 19 SNEEPERS 29 A-CHILTARIANS 9 KRYLORIANS 43 SOLONS 29 ALPHA CENTAURIANS 10 KT'KN 19 SSSTH 29 ARCTURANS 10 KYMELLIANS 19 stenth 29 ASTRANS 10 LANDLAKS 20 STONIANS 30 AUTOCRONS 11 LAXIDAZIANS 20 TAURIANS 30 axi-tun 45 LEM 20 technarchy 30 BA-BANI 11 LEVIANS 20 TEKTONS 38 BADOON 11 LUMINA 21 THUVRIANS 31 BETANS 11 MAKLUANS 21 TRIBBITES 31 CENTAURIANS 12 MANDOS 43 tribunals 48 CENTURII 12 MEGANS 21 TSILN 31 CIEGRIMITES 41 MEKKANS 21 tsyrani 48 CHR’YLITES 45 mephitisoids 46 UL'LULA'NS 32 CLAVIANS 12 m'ndavians 22 VEGANS 32 CONTRAXIANS 12 MOBIANS 43 vorms 49 COURGA 13 MORANI 36 VRELLNEXIANS 32 DAKKAMITES 13 MYNDAI 22 WILAMEANIS 40 DEONISTS 13 nanda 22 WOBBS 44 DIRE WRAITHS 39 NYMENIANS 44 XANDARIANS 40 DRUFFS 41 OVOIDS 23 XANTAREANS 33 ELAN 13 PEGASUSIANS 23 XANTHA 33 ENTEMEN 14 PHANTOMS 23 Xartans 49 ERGONS 14 PHERAGOTS 44 XERONIANS 33 FLB'DBI 14 plodex 46 XIXIX 33 FOMALHAUTI 14 POPPUPIANS 24 YIRBEK 38 FONABI 15 PROCYONITES 24 YRDS 49 FORTESQUIANS 15 QUEEGA 36 ZENN-LAVIANS 34 FROMA 15 QUISTS 24 Z'NOX 38 GEGKU 39 QUONS 25 ZN'RX (Snarks) 34 GLX 16 rajaks 47 ZUNDAMITES 34 GRAMOSIANS 16 REPTOIDS 25 Races Reference Table 51 GRUNDS 16 Rhunians 25 Blank Alien Race Sheet 54 1 The Universe of Marvel: Spacecraft and Aliens for the Marvel Super Heroes Game By David Edward Martin & Andrew James McFayden With help by TY_STATES , Aunt P and the crowd from www.classicmarvel.com . -

Carnegie Mellon University Notice

Carnegie Mellon University Notice This video and all related information and materials (“materials”) are owned by Carnegie Mellon University. These materials are provided on an “as-is” “as available” basis without any warranties and solely for your personal viewing and use. You agree that Carnegie Mellon is not liable with respect to any materials received by you as a result of viewing the video, or using referenced websites, and/or for any consequences or the use by you of such materials. By viewing, downloading, and/or using this video and related materials, you agree that you have read and agree to our terms of use (www.sei.cmu.edu/legal/). © 2015 Carnegie Mellon University. CERT® Alignment with Cyber COI Challenges and Gaps SEI Webinar 1 © 2015 Carnegie Mellon University Copyright 2015 Carnegie Mellon University This material is based upon work funded and supported by the Department of Defense under Contract No. FA8721-05-C-0003 with Carnegie Mellon University for the operation of the Software Engineering Institute, a federally funded research and development center. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Department of Defense. NO WARRANTY. THIS CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY AND SOFTWARE ENGINEERING INSTITUTE MATERIAL IS FURNISHED ON AN “AS-IS” BASIS. CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY MAKES NO WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, AS TO ANY MATTER INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, WARRANTY OF FITNESS FOR PURPOSE OR MERCHANTABILITY, EXCLUSIVITY, OR RESULTS OBTAINED FROM USE OF THE MATERIAL. -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

ALEX ROSS' Unrealized

Fantastic Four TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.118 February 2020 $9.95 1 82658 00387 6 ALEX ROSS’ DC: TheLost1970s•FRANK THORNE’sRedSonjaprelims•LARRYHAMA’sFury Force• MIKE GRELL’sBatman/Jon Sable•CLAREMONT&SIM’sX-Men/CerebusCURT SWAN’s Mad Hatter• AUGUSTYN&PAROBECK’s Target•theill-fatedImpact rebootbyPAUL lost pagesfor EDHANNIGAN’sSkulland Bones•ENGLEHART&VON EEDEN’sBatman/ GREATEST STORIESNEVERTOLDISSUE! KUPPERBERG •with unpublished artbyCALNAN, COCKRUM, HA,NETZER &more! Fantastic Four Four Fantastic unrealized reboot! ™ Volume 1, Number 118 February 2020 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Brian Augustyn Alex Ross Mike W. Barr Jim Shooter Dewey Cassell Dave Sim Ed Catto Jim Simon GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Alex Ross and the Fantastic Four That Wasn’t . 2 Chris Claremont Anthony Snyder An exclusive interview with the comics visionary about his pop art Kirby homage Comic Book Artist Bryan Stroud Steve Englehart Roy Thomas ART GALLERY: Marvel Goes Day-Glo. 12 Tim Finn Frank Thorne Inspired by our cover feature, a collection of posters from the House of Psychedelic Ideas Paul Fricke J. C. Vaughn Mike Gold Trevor Von Eeden GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The “Lost” DC Stories of the 1970s . 15 Grand Comics John Wells From All-Out War to Zany, DC’s line was in a state of flux throughout the decade Database Mike Grell ROUGH STUFF: Unseen Sonja . 31 Larry Hama The Red Sonja prelims of Frank Thorne Ed Hannigan Jack C. Harris GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Cancelled Crossover Cavalcade . -

{PDF EPUB} Thrill Book! 50'S Horror and SF Comics by Alex Toth

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Thrill Book! 50's Horror and S.F. Comics by Alex Toth Dick Briefer's Frankenstein: The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics HC (2010 IDW) comic books. This item is not in stock. If you use the "Add to want list" tab to add this issue to your want list, we will email you when it becomes available. The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics: Book 1 - 1st printing. The first volume in Yoe Book's thrilling new series, "The Masters of Horror Comic Book Library," fittingly features the first and foremost maniacal monster of all time. Frankenstein! Dick Briefer is one of the seminal artists who worked with Will Eisner on some of the very first comic books. If you like the comic-book weirdness of cartoonists Fletcher Hanks, Basil Wolverton, and Boody Rogers, you're sure to thrill over Dick Briefer's creation of Frankenstein. The large-format book lovingly reproduces a monstrous number of stories from the original 1940s and '50s comic books. The stories are fascinatingly supplemented by an insightful introduction with rare photos of the artist, original art, letters from Dick Briefer, drawings by Alex Toth inspired by Briefer's Frankenstein-and much more! Hardcover, 112 pages, full color. Cover price $21.99. This item is not in stock. If you use the "Add to want list" tab to add this issue to your want list, we will email you when it becomes available. The Chilling Archives of Horror Comics: Book 1 - 2nd or later printings. The first volume in Yoe Book's thrilling new series, "The Masters of Horror Comic Book Library," fittingly features the first and foremost maniacal monster of all time. -

M AA Teamups.Wps

Marvel : Avengers Alliance team-ups by Team-Up name _ Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. (50 points) = Black Widow / Hawkeye / Mockingbird Ambulancechasers (50 points) = Dare Devil / She Hulk Arachnophobia (50 points) = Spiderman / Black Widow / Spiderwoman Asgard (50 points) = Thor / Sif Assemble (50 points) = Thor / Hulk / Hawkeye / Black Widow / Ironman / Captain America Aviary (50 points) = all Heroes with a Flying ability Best Coast (50 points) = Hawkeye / Mockingbird / War Machine Birds of a Feather (50 points)= Hawkeye / Mockingbird Bloodlust (50 points) = Wolverine / Black Cat / Sif Cat Fight (50 points) = Kitty Pryde / Black Cat Cosplayers (50 points) = Spiderman / Black Cat Defenders (50 points) = Dr.Strange / Hulk Egghead (50 points) = Hulk / Spiderman / Ironman / Mr.Fantastic Fantastic 4 (50 points) = all Fantastic 4 members Frenemies, Assemble (50 points) = Hawkeye / Black Widow Green Giants (50 points) = She-Hulk / Hulk Heroesforhire (50 points) = Luke Cage / Iron Fist Hard and Soft (50 points) = Kitty Pryde / Colossus Hotstuff (50 points) = Phoenix / Human Torch Illuminati (50 points) = Dr.Strange / Mr.Fantastic / Ironman King&Queen (50 points) = Black Panther / Storm Marvelous (50 points) = Phoenix / Ms. Marvel Sibling Rivalry (50 points) = Invisible Woman / Human Torch Tinmen (50 points) = War Machine / Iron Man Tossers (50 points) = Thing / Hulk / She-Hulk / Phoenix X-Force (50 points) = all X-Men members X-lovers (50 points) = Cyclops / Phoenix by Hero name _ Black Cat + Wolverine / Black Cat / Sif = Bloodlust (50 points) Black Cat + Kitty Pryde = Cat Fight (50 points) Black Cat + Spiderman = Cosplayers (50 points) Black Panther + Storm = King&Queen (50 points) Black Widow + Hawkeye / Mockingbird = Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. -

Katalog Zur Ausstellung "60 Jahre Marvel

Liebe Kulturfreund*innen, bereits seit Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs befasst sich das Amerikahaus München mit US- amerikanischer Kultur. Als US-amerikanische Behörde war es zunächst für seine Bibliothek und seinen Lesesaal bekannt. Doch schon bald wurde das Programm des Amerikahauses durch Konzerte, Filmvorführungen und Vorträge ergänzt. Im Jahr 1957 zog das Amerika- haus in sein heutiges charakteristisches Gebäude ein und ist dort, nach einer vierjährigen Generalsanierung, seit letztem Jahr wieder zu finden. 2014 gründete sich die Stiftung Bay- erisches Amerikahaus, deren Träger der Freistaat Bayern ist. Heute bietet das Amerikahaus der Münchner Gesellschaft und über die Stadt- und Landesgrenzen hinaus ein vielfältiges Programm zu Themen rund um die transatlantischen Beziehungen – die Vereinigten Staaten, Kanada und Lateinamerika- und dem Schwerpunkt Demokratie an. Unsere einladenden Aus- stellungräume geben uns die Möglichkeit, Werke herausragender Künstler*innen zu zeigen. Mit dem Comicfestival München verbindet das Amerikahaus eine langjährige Partnerschaft. Wir freuen uns sehr, dass wir mit der Ausstellung „60 Jahre Marvel Comics Universe“ bereits die fünfte Ausstellung im Rahmen des Comicfestivals bei uns im Haus zeigen können. In der Vergangenheit haben wir mit unseren Ausstellungen einzelne Comickünstler, wie Tom Bunk, Robert Crumb oder Denis Kitchen gewürdigt. Vor zwei Jahren freute sich unser Publikum über die Ausstellung „80 Jahre Batman“. Dieses Jahr schließen wir mit einem weiteren Jubiläum an und feiern das 60-jährige Bestehen des Marvel-Verlags. Im Mainstream sind die Marvel- Helden durch die in den letzten Jahren immer beliebter gewordenen Blockbuster bekannt geworden, doch Spider-Man & Co. gab es schon lange davor. Das Comic-Heft „Fantastic Four #1“ gab vor 60 Jahren den Startschuss des legendären Marvel-Universums.