Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wooltru Healthcare Fund Optical Network List Gauteng

WOOLTRU HEALTHCARE FUND OPTICAL NETWORK LIST GAUTENG PRACTICE TELEPHONE AREA PRACTICE NAME PHYSICAL ADDRESS CITY OR TOWN NUMBER NUMBER ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE ACTONVILLE 084 6729235 AKASIA 7033583 MAKGOTLOE SHOP C4 ROSSLYN PLAZA, DE WAAL STREET, ROSSLYN AKASIA 012 5413228 AKASIA 7025653 MNISI SHOP 5, ROSSLYN WEG, ROSSLYN AKASIA 012 5410424 AKASIA 668796 MALOPE SHOP 30B STATION SQUARE, WINTERNEST PHARMACY DAAN DE WET, CLARINA AKASIA 012 7722730 AKASIA 478490 BODENSTEIN SHOP 4 NORTHDALE SHOPPING, CENTRE GRAFENHIEM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 012 5421606 AKASIA 456144 BODENSTEIN SHOP 4 NORTHDALE SHOPPING, CENTRE GRAFENHIEM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 012 5421606 AKASIA 320234 VON ABO & LABUSCHAGNE SHOP 10 KARENPARK CROSSING, CNR HEINRICH & MADELIEF AVENUE, KARENPARK AKASIA 012 5492305 AKASIA 225096 BALOYI P O J - MABOPANE SHOP 13 NINA SQUARE, GRAFENHEIM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 087 8082779 ALBERTON 7031777 GLUCKMAN SHOP 31 NEWMARKET MALL CNR, SWARTKOPPIES & HEIDELBERG ROAD, ALBERTON ALBERTON 011 9072102 ALBERTON 7023995 LYDIA PIETERSE OPTOMETRIST 228 2ND AVENUE, VERWOERDPARK ALBERTON 011 9026687 ALBERTON 7024800 JUDELSON ALBERTON MALL, 23 VOORTREKKER ROAD, ALBERTON ALBERTON 011 9078780 ALBERTON 7017936 ROOS 2 DANIE THERON STREET, ALBERANTE ALBERTON 011 8690056 ALBERTON 7019297 VERSTER $ VOSTER OPTOM INC SHOP 5A JACQUELINE MALL, 1 VENTER STREET, RANDHART ALBERTON 011 8646832 ALBERTON 7012195 VARTY 61 CLINTON ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 011 9079019 ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN 26 VOORTREKKER STREET ALBERTON 011 9078745 -

Designing the South African Nation from Nature to Culture

CHAPTER 3 Designing the South African Nation From Nature to Culture Jacques Lange and Jeanne van Eeden There is to date very little published research and writing about South African design history. One of the main obstacles has been dealing with the legacy of forty years of apartheid censorship (1950 to 1990) that banned and destroyed a vast array of visual culture in the interests of propaganda and national security, according to the Beacon for Freedom of Expression (http://search.beaconforfreedom.org/about_database/south%20africa.html). This paucity of material is aggravated by the general lack of archival and doc- umentary evidence, not just of the struggle against apartheid, but also of the wider domain of design in South Africa. Even mainstream designed mate- rial for the British imperialist and later apartheid government has been lost or neglected in the inadequate archival facilities of the State and influential organizations such as the South African Railways. Efforts to redress this are now appearing as scholars start to piece together fragments, not in order to write a definitive history of South African design, but rather to write histories of design in South Africa that recuperate neglected narratives or revise earlier historiographies. This chapter is accordingly an attempt to document a number of key moments in the creation of South African nationhood between 1910 and 2013 in which communication design played a part. Our point of departure is rooted in Zukin’s (1991: 16) belief that symbolic and material manifestations of power harbour the ideological needs of powerful institutions to manipulate class, gender and race relations, ultimately to serve the needs of capital (and governance). -

Tender Bulletin: 30 October 2009

Government Tender Bulletin REPUBLICREPUBLIC OF OF SOUTH SOUTH AFRICAAFRICA Vol. 532 Pretoria, 30 October 2009 No. 2606 This document is also available on the Internet on the following web sites: 1. http://www.treasury.gov.za 2. http://www.info.gov.za/view/DynamicAction?pageid=578 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINEHELPLINE: 08000800-123-22 123 22 PreventionPrevention is is the the cure cure G09-191808—A 2606—1 2 GOVERNMENT TENDER BULLETIN, 30 OCTOBER 2009 INDEX Page No. Instructions.................................................................................................................................. 8 A. BID INVITED FOR SUPPLIES, SERVICES AND DISPOSALS < SUPPLIES: CLOTHING/TEXTILES .................................................................................. 11 < SUPPLIES: GENERAL...................................................................................................... 11 < SUPPLIES: MEDICAL ....................................................................................................... 18 < SUPPLIES: PERISHABLE PROVISIONS......................................................................... 18 < SERVICES: BUILDING ..................................................................................................... 19 < SERVICES: CIVIL ............................................................................................................. 22 < SERVICES: ELECTRICAL -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

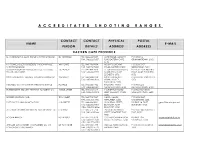

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Hoofstuk 10 Ondersteuning Van Militere

HOOFSTUK 10 ONDERSTEUNING VAN MILITERE AKTIWITEITE DEUR DIE VAALDRIEHOEKSE GEMEENSKAP 10.1 INLEIDING Reeds in die Tweede Wereldoorlog was daar pogings in die Vaaldriehoek om die oorlog te ondersteun.1 Net so is in die era 1974-1994 verskillende pogings deur die gemeenskap van die Vaaldriehoek geloods om die verdedigingspoging van voorgenoemde tydperk te ondersteun. As gevolg van diensplig en grensdiens sedert die sewentige~are, is die gemeenskap toenemend by militere aktiwiteite betrek.2 Veral vroue-organisasies het die verdedigingspoging aktief ondersteun.3 Die bree blanke gemeenskap het geldelik bygedra omdat hulle seuns by die weermag of polisie betrokke was. Daar was pogings om teruggekeerde dienspligtiges weer in die samelewing te laat inskakel. lnsamelingsprojekte is vir die grenssoldate aangepak, vervoerreelings vir dienspligtiges getref en die bonusobligasieveldtog is ook ondersteun. Werkgewers het soldate met salarisse tegemoet gekom. Die weermag het aan die ander kant op verskillende wyses bygedra om die gemeenskap te ondersteun. 1 Vgl. Vaal Teknorama (VTR), Houer stadsraaddokumente, Leer Warfund drives, Brief van die organiseerder van Military Cavalcade: Woman's Section Liberty Cavalcade aan burgemeester van Vereeniging, 02.01.1942. 2 J. Cock, Manpower and militarisation; woman in the SADF in J. Cock & L. Nathan (eds.)., War and society: The m~itarisation of South African politics (Johannesburg, David Phillip, 1989), p. 52; E. Fourie, "Ek praatmy hart uit", Paratus, 29(4), Aparil1978, p. 10. 3 J. Cock, Manpower and militarisation; -

National Liquor Authority Register

NATIONAL LIQUOR AUTHORITY REGISTER - 30 JUNE 2013 Registration Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Transfer & (or) Date of Number Permitted Registration Relocations Cancellation RG 0006 The South African Breweries Limited Sab -(Gauteng) M & D 3 Fransen Str, Chamber GP 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0007 Greytown Liquor Distributors Greytown Liquor Distributors D Lot 813, Greytown, Durban KZN 2005/02/25 N/A N/A RG 0008 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Groblersdal) D 16 Linbri Avenue, Groblersdal, 0470 MPU N/A 28/01/2011 RG 0009 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Ga D Stand 14, South Street, Ga-Rankuwa, 0208 NW N/A 27/09/2011 Rankuwa) RG 0010 The South African Breweries Limited Sab (Port Elizabeth) M & D 47 Kohler Str, Perseverence, Port Elizabeth EC 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0011 Lutzville Vineyards Ko-Op Ltd Lutzville Vineyards Ko-Op Ltd M & D Erf 312 Kuils River, Pinotage Str, WC 2008/02/20 N/A N/A Saxenburg Park, Kuils River RG 0012 Louis Trichardt Beer Wholesalers (Pty) Louis Trichardt Beer Wholesalers D Erf 05-04260, Byles Street, Industrial Area, LMP 2005/06/05 N/A N/A Ltd Louis Trichardt, Western Cape RG 0013 The South African Breweries Limited Sab ( Newlands) M & D 3 Main Road, Newlands WC 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0014 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Rustenburg) D Erf 1833, Cnr Ridder & Bosch Str, NW 2007/10/19 02/03/2011 Rustenburg RG 0015 Madadeni Beer Wholesalers (Pty) Ltd Madadeni Beer Wholesalers (Pty) D Lot 4751 Section 7, Madadeni, Newcastle, KZN -

The Psychological Impact of Guerrilla Warfare on the Boer Forces During the Anglo-Boer War

University of Pretoria etd - McLeod AJ (2004) THE PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT OF GUERRILLA WARFARE ON THE BOER FORCES DURING THE ANGLO-BOER WAR by ANDREW JOHN MCLEOD Submitted as partial requirement for the degree DOCTOR PHILOSOPHIAE (HISTORY) in the Faculty of Human Sciences University of Pretoria Pretoria 2004 Supervisor : Prof. F. Pretorius Co-supervisor : Prof. J.B. Schoeman University of Pretoria etd - McLeod AJ (2004) Abstract of: “The psychological impact of guerrilla warfare on the Boer forces during the Anglo- Boer War” The thesis is based on a multi disciplinary study involving both particulars regarding military history and certain psychological theories. In order to be able to discuss the psychological experiences of Boers during the guerrilla phase of the Anglo-Boer War, the first chapters of the thesis strive to provide the required background. Firstly an overview of the initial conventional phase of the war is furnished, followed by a discussion of certain psychological issues relevant to stress and methods of coping with stress. Subsequently, guerrilla warfare as a global concern is examined. A number of important events during the transitional stage, in other words, the period between conventional warfare and total guerrilla warfare, are considered followed by the regional details concerning the Boers’ plans for guerrilla warfare. These details include the ecological features, the socio-economic issues of that time and military information about the regions illustrating the dissimilarity and variety involved. In the chapters that follow the focus is concentrated on the psychological impact of the guerrilla war on the Boers. The wide range of stressors (factors inducing stress) are arranged according to certain topics: stress caused by military situations; stress caused by the loss of infrastructure in the republics; stress caused by environmental factors; stress arising from daily hardships; stress caused by anguish and finally stressors prompted by an individuals disposition. -

January 2018

National Boer War Memorial Association National Patron: Air Chief Marshal Mark Binskin AC Volume 1, Issue 1 Chief of the Defence Force Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 11, No. 1 Queensland Chairman’s Report Welcome to our first Queensland Newsletter of 2018; in The inaugural meeting of the new committee was held on th fact, the first newsletter of the new committee. Monday, 27 November, 2017, at the Sherwood- Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch. I am Gordon Bold, Chairman of the new Queensland Committee. Just to keep you up to speed, a little back- In Queensland, we are hoping to evolve into some form of ground first, leading up to the appointment of a new a Boer War „Descendants & Supporters‟ Association (a committee… new name is yet to be finalised). The new committee intend meeting quarterly. However, at the moment we Now that the Boer War Memorial in Canberra has been are still under the guidance and advice of previous com- built and dedicated, the role of the Queensland Boer mittee members as the NBWMA still exists, due to a num- War Memorial Association (QBWMA) needed to revisit ber of issues that need resolution, prior to 30th June, its charter. Was it to be disbanded, now that the Mem- 2018. It is envisaged the NBWMA will then step down. orial in Canberra is complete, or continued, with a differ- ent charter? The Committee decided to continue with the previous th financial support arrangements. Members are invited to On Sunday 17 September, a meeting was held at the show their support by continuing their financial contribu- Sherwood-Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch. -

National Liquor Authority Register

National Liquor Register Q1 2021 2022 Registration/Refer Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Registration Transfer & (or) Date of ence Number Permitted Relocations or Cancellation alterations Ref 10 Aphamo (PTY) LTD Aphamo liquor distributor D 00 Mabopane X ,Pretoria GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 12 Michael Material Mabasa Material Investments [Pty] Limited D 729 Matumi Street, Montana Tuine Ext 9, Gauteng GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 14 Megaphase Trading 256 Megaphase Trading 256 D Erf 142 Parkmore, Johannesburg, GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 22 Emosoul (Pty) Ltd Emosoul D Erf 842, 845 Johnnic Boulevard, Halfway House GP 2016-10-07 N/A N/A Ref 24 Fanas Group Msavu Liquor Distribution D 12, Mthuli, Mthuli, Durban KZN 2018-03-01 N/A 2020-10-04 Ref 29 Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd D Erf 19, Vintonia, Nelspruit MP 2017-01-23 N/A N/A Ref 33 Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd D 117 Foresthill, Burgersfort LMP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 34 Media Active cc Media Active cc D Erf 422, 195 Flamming Rock, Northriding GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 52 Ocean Traders International Africa Ocean Traders D Erf 3, 10608, Durban KZN 2016-10-28 N/A N/A Ref 69 Patrick Tshabalala D Bos Joint (PTY) LTD D Erf 7909, 10 Comorant Road, Ivory Park GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 75 Thela Management PTY LTD Thela Management PTY LTD D 538, Glen Austin, Midrand, Johannesburg GP 2016-04-06 N/A 2020-09-04 Ref 78 Kp2m Enterprise (Pty) Ltd Kp2m Enterprise D Erf 3, Cordell -

Black South African History Pdf

Black south african history pdf Continue In South African history, this article may require cleaning up in accordance with Wikipedia quality standards. The specific problem is to reduce the overall quality, especially the lead section. Please help improve this article if you can. (June 2019) (Find out how and when to remove this message template) Part of the series on the history of the weapons of the South African Precolonial Middle Stone Age Late Stone Age Bantu expansion kingdom mapungubwe Mutapa Kaditshwene Dutch colonization of the Dutch Cape Colony zulu Kingdom of Shaka kaSenzangakhona Dingane kaSenzangakhona Mpande kaSenzangakhona Cetshwayo kaMpande Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo 1887 Annexation (British) British Colonization Cape Colony Colonia Natal Transvaal Colony Orange River Colony Bur Republic South African Orange Free Republic Natalia Republic Bur War First Storm War Jameson Reid Second World War Union of South Africa First World War of apartheid Legislation South African Border War Angolan Civil War Bantustans Internal Resistance to apartheid referendum after apartheid Mandela Presidency Motlante Presidency of the Presidency of the President zuma The theme of economic history of invention and the opening of the Military History Political History Religious History Slavery Timeline South Africa portalv Part series on Culture History of South Africa People Languages Afrikaans English Ndebele North Soto Sowazi Swazi Tswana Tsonga Venda Xhosa Zulus Kitchens Festivals Public Holidays Religion Literature Writers Music And Performing Arts