Distribution of Fish in Portland Tributary Streams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Individual Permit National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems Phase I Individual Permit

a Individual Permit National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems Phase I Individual Permit Oregon Department of Environmental Quality Stormwater Program 700 NE Multnomah St., Suite 600 Portland, OR 97232 Issued pursuant to Oregon Revised Statute 468B.050 and Section 402 of the Federal Clean Water Act Issued to: City of Portland Permit Number: 101314 Port of Portland File Number: 108015 Major Receiving Water Bodies: Basins Willamette River, Columbia River Sub-basins Lower Willamette River, Columbia Slough, Tualatin River Streams Columbia River, Columbia Slough, Fanno Creek, Balch Creek, Johnson Creek, and Tryon Creek Wasteload/Load Allocations (if any): A Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) that includes wasteload allocations for urban stormwater has been established for the Willamette River Basin, Tualatin River Subbasin, and the Columbia Slough. Waste Load Allocations are addressed in Schedule D of this permit. Sources Covered By This Permit This permit covers all existing and new discharges of stormwater from the Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) within the City of Portland Urban Services Boundary, in accordance with the requirements, limitations and conditions set forth. ___________________________________________ ________________________________ Christine Svetkovich Issuance Date: Water Quality Manager ________________________________ Effective Date: MS4 Phase I Individual Permit Portland Group Effective: Expiration: PERMITTED ACTIVITIES Until this permit expires, is modified or revoked, each co-permittee is authorized to discharge municipal stormwater to surface waters of the state only in conformance with the requirements, limitations and conditions set forth in the following schedules. Where conflict exists between specific conditions (found in Schedules A-D) and general conditions (Schedule F), the specific conditions supersede the general conditions. -

Geologic Map of the Sauvie Island Quadrangle, Multnomah and Columbia Counties, Oregon, and Clark County, Washington

Geologic Map of the Sauvie Island Quadrangle, Multnomah and Columbia Counties, Oregon, and Clark County, Washington By Russell C. Evarts, Jim E. O'Connor, and Charles M. Cannon Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3349 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. Suggested citation: Evarts, R.C., O'Connor, J.E., and Cannon, C.M., 2016, Geologic map of the Sauvie Island quadrangle, Multnomah and Columbia Counties, Oregon, and Clark County, Washington: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3349, scale 1:24,000, pamphlet 34 p., http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/sim3349. ISSN 2329-132X (online) Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Timing of In-Water Work to Protect Fish and Wildlife Resources

OREGON GUIDELINES FOR TIMING OF IN-WATER WORK TO PROTECT FISH AND WILDLIFE RESOURCES June, 2008 Purpose of Guidelines - The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, (ODFW), “The guidelines are to assist under its authority to manage Oregon’s fish and wildlife resources has updated the following guidelines for timing of in-water work. The guidelines are to assist the the public in minimizing public in minimizing potential impacts to important fish, wildlife and habitat potential impacts...”. resources. Developing the Guidelines - The guidelines are based on ODFW district fish “The guidelines are based biologists’ recommendations. Primary considerations were given to important fish species including anadromous and other game fish and threatened, endangered, or on ODFW district fish sensitive species (coded list of species included in the guidelines). Time periods were biologists’ established to avoid the vulnerable life stages of these fish including migration, recommendations”. spawning and rearing. The preferred work period applies to the listed streams, unlisted upstream tributaries, and associated reservoirs and lakes. Using the Guidelines - These guidelines provide the public a way of planning in-water “These guidelines provide work during periods of time that would have the least impact on important fish, wildlife, and habitat resources. ODFW will use the guidelines as a basis for the public a way of planning commenting on planning and regulatory processes. There are some circumstances where in-water work during it may be appropriate to perform in-water work outside of the preferred work period periods of time that would indicated in the guidelines. ODFW, on a project by project basis, may consider variations in climate, location, and category of work that would allow more specific have the least impact on in-water work timing recommendations. -

Portland Harbor RI/FS Draft Final Remedial Investigation Report April 27, 2015

Portland Harbor RI/FS Draft Final Remedial Investigation Report April 27, 2015 3.0 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING This section describes the current and historical physical characteristics and human uses of the Portland Harbor Superfund Site. Physical characteristics of the site include meteorology, regional geology and hydrogeology, surface water hydrology, the physical system (which includes bathymetry, sediment characteristics, and hydrodynamics and sediment transport), habitat, and surface features. Human characteristics of the site that are discussed here include historical and current land and river use, the municipal sewer system, and human access and use. In addition to providing context to the RI sampling and analysis, the factors presented in this section are considered in the refinement of the Study Area-wide CSM, which is presented in Section 10. Sections 3.1 through 3.7 focuses primarily on the physical setting within the Study Area (RM 1.9 to 11.8). However, the physical features of the Willamette River from Willamette Falls (RM 26) to the Columbia River (RM 0), as well as the upstream portion of Multnomah Channel, are discussed as needed to place the Study Area’s physical characteristics into a regional context. The Willamette River basin has a drainage area of 11,500 square miles and is bordered by foothills and mountains of the Cascade and Coast ranges up to 10,000 feet high to the south, east, and west (Trimble 1963). The main channel of the Willamette forms in the southern portion of the valley near Eugene, at the convergence of the Middle and Coast forks. It flows through the broad and fertile Willamette Valley region and at Oregon City flows over the Willamette Falls and passes through Portland before joining the Columbia River (Map 3.1-1). -

TMDL Implementation Plan Annual Report

City of Portland, Oregon Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Implementation Plan Fourth Annual Status Report Fiscal Year 2011-2012 (July 1, 2011 – June 30, 2012) Submitted to: Oregon Department of Environmental Quality November 1, 2012 TMDL Implementation Plan Fourth Annual Status Report November 1, 2012 Introduction This Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Implementation Plan Fourth Annual Status Report summarizes key activities and accomplishments for the City of Portland (City) during fiscal year (FY) 2011-2012 (July 1, 2011 to June 30, 2012). This is the fourth annual status report submitted by the City following the approval of the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Implementation Plan (IP) on March 6, 2009, in accordance with the Willamette Basin TMDL Water Quality Management Plan (WQMP). The IP was updated in FY11-12 to reflect the revised National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Stormwater Management Plan (SWMP), and the updated portion was included in the third annual status report. This report does not encompass all elements of the TMDL Implementation Plan, but rather focuses on the most important implementation actions. It also does not quantify the pollutant load reduction of every activity because reliable, consistent, and universally accepted tools are currently not available to assess pollutant load reduction effectiveness of many of the actions (e.g., pollution prevention, education, stream restoration). For parameters with EPA-approved stormwater-related TMDL Waste Load Allocations (WLAs), pollutant load reductions from structural facilities within the City’s MS4 area are estimated as part of NPDES MS4 permit compliance. That evaluation was most recently conducted as part of the 2008 NPDES MS4 Permit Renewal Submittal (http://www.portlandonline.com/bes/index.cfm?c=50333&a=246071). -

3.2 Flood Level of Risk* to Flooding Is a Common Occurrence in Northwest Oregon

PUBLIC COMMENT DRAFT 11/07/2016 3.2 Flood Level of Risk* to Flooding is a common occurrence in Northwest Oregon. All Flood Hazards jurisdictions in the Planning Area have rivers with high flood risk called Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHA), except Wood High Village. Portions of the unincorporated area are particularly exposed to high flood risk from riverine flooding. •Unicorporated Multnomah County Developed areas in Gresham and Troutdale have moderate levels of risk to riverine flooding. Preliminary Flood Insurance Moderate Rate Maps (FIRMs) for the Sandy River developed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in 2016 •Gresham •Troutdale show significant additional risk to residents in Troutdale. Channel migration along the Sandy River poses risk to Low-Moderate hundreds of homes in Troutdale and unincorporated areas. •Fairview Some undeveloped areas of unincorporated Multnomah •Wood Village County are subject to urban flooding, but the impacts are low. Developed areas in the cities have a more moderate risk to Low urban flooding. •None Levee systems protect low-lying areas along the Columbia River, including thousands of residents and billions of dollars *Level of risk is based on the local OEM in assessed property. Though the probability of levee failure is Hazard Analysis scores determined by low, the impacts would be high for the Planning Area. each jurisdiction in the Planning Area. See Appendix C for more information Dam failure, though rare, can causing flooding in downstream on the methodology and scoring. communities in the Planning Area. Depending on the size of the dam, flooding can be localized or extreme and far-reaching. -

Fanno Creek and Tributaries Conservation Plan

Fanno Creek and Tributaries Conservation Plan Volume One: Inventory, Analysis, and Regulations for the Protection and Restoration ofFish and Wildlife Habitats, Natural Areas, Water Bodies, and Wetlands and Volume Four: Revised Zoning Maps Final Plan As Adopted bythe CityCouncil City of Portland, Oregon Bureau of Planning Adopted by Ordinance Number 167293, as Amended, onJanuary 19, 1994 Effective January 19, 1994 If you need a large-print copy of this report, Please call 823-7700 (or TDD 823-6868). Portland City Council Vera Katz, Mayor Earl Blumenauer, Commissioner Charlie Hales, Commissioner Gretchen Kafoury, Commissioner Michael lindberg, Commissioner Portland Planning Commission Richard Cooley, President Richard Michaelson, Vice President Joan Brown-Klein Bruce Fong Margaret Kirkpatrick. Vivian Parker Paul Schuback. Douglas Van Dyk Fanno Creek and Tributaries Conservation Plan Volume One: Inventory, Analysis, and Regulations for the Protection and Restoration of Fish and Wildlife Habitats, Natural Areas, Water Bodies, and Wetlands Bureau of Planning Charlie Hales, Commissioner-In-Charge David Knowles, Interim Planning Director Robert E. Clay, Chief of Long Range Planning and Urban Design Project Manager AI Burns, City Planner Project Jlssistance Charles Beasley, Project Research Jessica Richman, City Planner Damian Syrnyk, City Planner Peter Hurley, Planning Jlssistant Robert Goldie, Information System Analyst Linda Torgeson, Graphic lliustrator Geoff Sauncy, Graphic lllustrator January 19,1994 Substitute Ordinance No. 16 7 293 As Amended ·Protect and Conserve Natural Resources within the Fanno Creek Watershed. (Ordinance: amend Comprehensive Plan, Zoning Maps, and Title 33, Planning and Zonin~) The City of Portland Ordains: Section 1. The Council fmds: General Findings 1. The Fauno Creek Watershed contains many significant natural resources that are worthy of protection or conservation. -

Title 13 – Nature in Neighborhoods R Equest for Metro Determination of Substantial Compliance

TITLE 13 – NATURE IN NEIGHBORHOODS R equest for Metro Determination of Substantial Compliance December 2012 Accepted by Portland City Council November 28, 2012 www.portlandoregon.gov/bps The Bureaus of Planning and Sustainability and Transportation are committed to providing equal access to information and hearings. If you need special accommodation, please call 503-823-7700, the City’s TTY at 503-823-6868, or the Oregon Relay Service at 1-800-735-2900. To obtain a copy of this document or more information about this project, please contact: Roberta Jortner, Senior Environmental Planner Bureau of Planning and Sustainability 1900 SW 4th Avenue, Suite 7100 Portland, OR 97201 Phone: 503-823-7855 | Email: [email protected] II TITLE 13, NATURE IN NEIGHBORHOODS – CITY OF PORTLAND COMPLIANCE REQUEST – DECEMBER 2012 A cknowledgements City Council B ureau of Environmental Services Sam Adams, Mayor and Commissioner in Charge Shannah Anderson Nick Fish Jane Bacchieri Amanda Fritz Susan Barthel Randy Leonard Mitch Bixby Dan Saltzman Eli Callison Amber Clayton Planning and Sustainability Commission Sara Culp Linda Dobson André Baugh, Chair Rhonda Fast Howard Shapiro, Vice Chair Robert Fraley Michelle Rudd, Vice Chair Emily Hauth Karen Gray Dawn Hottenroth Don Hanson Michele Juon Mike Houck Jennifer Karps Lai-Lani Ovalles Paul Ketcham Jill Sherman Kaitlin Lovell Chris Smith Dominic Maze Mike Rosen B ureau of Planning and Sustainability Darian Santner Susan Anderson, Director Marie Johnson Walkiewicz Joe Zehnder, Chief Planner Sallie -

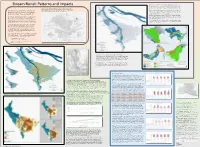

Portland's Delineated Stream Desert

The City of Portland Bureau of Environmental Services collects water quality and habitat data by subwatershed in Stream Burial: Patterns and Impacts multiple capacities. The data represented below was collected in monthly grab samples between 2008 and 2016. Upstream samples were taken from open channels in environmental protection or conservation areas. Downstream samples were taken from pipes, culverts, or outfalls. For each stream in the study, the downstream reaches are considered to be heavily “For more than two hours yesterday Johnson and Tanner Creeks were turned from their beds, and poured their yellow torrents altered by development. The figures below indicate average upstream and downstream values and the difference between through paved streets, filling cellars of some of the fine residents along the foot of the hill, tearing deep ruts in gutter drains, them. Stream burial is a common pattern of urban development that originated in the late 1800s with early overturning wooden sidewalks, and temporarily impeding street traffic in many places. So great was the volume of water that people Tanner Creek is piped from its headwaters in a conservation zone to its confluence at milepost 11 in the Willamette River. urbanization. Over the last 150 years, stream channels across urban areas have been altered, buried, and generally thought that the costly sewers that were built to swallow up the troublesome creeks, had burst, and preparations were in Tanner Creek runs in pipes directly under Portland’s urban core and has cultural importance as one of the city’s most diverted, creating riverless urban centers called urban stream deserts (Napieralski et al., 2015). -

Greater Forest Park Conservation Initiative Mapping the Trail to a Healthy and Sustainable Forest Park

Greater Forest Park Conservation Initiative Mapping the trail to a healthy and sustainable Forest Park. Prepared by: THE FOREST PARK CONSERVANCY IN COLLABORATION WITH THE FOREST PARK ALLIANCE. Greater Forest Park Conservation Initiative | 1 Greater Forest Park Conservation Initiative Prepared by THE FOREST PARK CONSERVANCY IN COLLABORATION WITH THE FOREST PARK ALLIANCE November 2013 Greater Forest Park Conservation Initiative | 2 SUGGESTED CITATION Forest Park Conservancy and Forest Park Alliance. 2013. Greater Forest Park Conservation Initiative. R. Myers, principal author. www.forestparkconservancy.org FOREST PARK ALLIANCE MEMBERS Audubon Society of Portland City of Portland Bureau of Environmental Services Columbia Land Trust Forest Park Conservancy Forest Park Neighborhood Association Friends of Trees Linnton Neighborhood Association Metro Regional Government Portland Parks & Recreation The Intertwine Alliance West Multnomah Soil & Water Conservation District Greater Forest Park Conservation Initiative | 3 Preface In 2008 the Friends of Forest Park became the Forest Park Conservancy. This transition was more than just a change of name. It indicated a maturing of the organization and an intention to be a stronger and more capable part- ner to the park’s owner and operator, Portland Parks & Recreation. It sig- naled a readiness for greater conservation leadership. The new identity brought with it new questions. Where do we stand in our efforts to restore and protect Forest Park? What is our ultimate vision for the park’s ecological health? Are we on course to achieve that vision and if not, how should we respond? How do we best engage residents of the Portland region with the park’s future? What is our responsibility not just to the park but to the greater landscape with which the park is so deeply intertwined? If the Forest Park Conservancy was to live up to its new name, it needed to find its footing among these fundamental questions. -

Fanno Creek Greenway Action Plan Section I

FANNO CREEK GREENWAY TRAIL ACTION PLAN January 2003 Prepared for: Metro Regional Parks and Greenspaces Department Prepared by: Alta Planning + Design METRO COUNCIL FANNO CREEK GREENWAY TRAIL ACTION PLAN WORKING GROUP MEMBERS David Bragdon, President Rex Burkholder Commissioner Dick Schouten, Washington County Carl Hostica Joanne Rice, Washington County Land Use and Transportation Susan McLain Aisha Willits, Washington County Land Use and Transportation Rod Monroe Anna Zirker, Tualatin Hills Park and Recreation District Brian Newman Margaret Middleton, City of Beaverton Transportation Rod Park Roel Lundquist, City of Durham Administrator Duane Roberts, City of Tigard Community Development METRO AUDITOR Justin Patterson, City of Tualatin Parks Jim Sjulin, Portland Parks and Recreation Alexis Dow, CPA Gregg Everhart, Portland Parks and Recreation Courtney Duke, Portland Transportation METRO REGIONAL PARKS AND GREENSPACES DEPARTMENT Don Baack, SWTrails Group of Southwest Neighborhoods, Inc. Bob Bothman, 40-Mile Loop Land Trust Jim Desmond, Director Dave Drescher, Fans of Fanno Creek Heather Kent, Planning and Education Division Manager Sue Abbott, National Park Service Rivers and Trails Program Heather Kent, Metro Planning and Education Division ALTA PLANNING + DESIGN William Eadie, Metro Open Spaces Acquisition Division Bill Barber, Metro Planning George Hudson, Principal Arif Khan, Senior Planner Daniel Lerch, Assistant Planner PROJECT MANAGER Mel Huie, Metro Regional Parks and Greenspaces Department For more information or copies of this report, contact: Mel Huie, Regional Trails Coordinator (503) 797-1731, [email protected] Metro Regional Services Alta Planning + Design 600 NE Grand Ave. 144 NE 28th Ave. Portland, OR 97232 Portland, OR 97232 (503) 797-1700 (503) 230-9862 www.metro-region.org www.altaplanning.com FANNO CREEK GREENWAY TRAIL ACTION PLAN Contents I. -

Stephens Creek Stormwater System Plan

BUREAU OF ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES • CITY OF PORTLAND Stephens Creek Stormwater System Plan n January 2013 Dan Saltzman, Commissioner Dean Marriott, Director DAN SALTZMAN, COMMISSIONER • DEAN MARRIOTT, DIRECTOR January 2013 RE: Stephens Creek Stormwater System Plan Dear Readers, The Bureau of Environmental Services is pleased to publish the Stephens Creek Stormwater System Plan. It is the result of a multi‐year pilot to analyze and put forth recommendations to improve both stormwater infrastructure and watershed health conditions in the Stephens Creek watershed. We are excited to report that the exercise was successful and that the lessons learned will inform the citywide approach to stormwater system planning. While Portland emphasizes managing stormwater at the source, Stephens Creek and conditions in southwest Portland challenge this approach. A system perspective is necessary to characterize overall condition and performance in order to tailor stormwater improvements and requirements to meet system needs. This approach will apply to other parts of the city where different challenges exist, and it will inform the next Stormwater Management Manual update. Understanding that the health and growth of our community depends on infrastructure, our charge is to find ways stormwater infrastructure can serve multiple functions and benefits. Infrastructure that filters, collects, conveys, and discharges stormwater is a visible part of our community, and its appearance contributes to the character of an area. Rather than burying stormwater and sending the problems downstream, we benefit by exposing it to air and plants, allowing it to recharge groundwater, and create spaces that support parks, transportation and other community needs. Broad and complex interests have a stake in the stormwater system.