A Fantasy Subverting the Woman‟S Image As “The Angel in the House”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angel Sanctuary, a Continuation…

Angel Sanctuary, A Continuation… Written by Minako Takahashi Angel Sanctuary, a series about the end of the world by Yuki Kaori, has entered the Setsuna final chapter. It is appropriately titled "Heaven" in the recent issue of Hana to Yume. However, what makes Angel Sanctuary unique from other end-of-the-world genre stories is that it does not have a clear-cut distinction between good and evil. It also displays a variety of worldviews with a distinct and unique cast of characters that, for fans of Yuki Kaori, are quintessential Yuki Kaori characters. With the beginning of the new chapter, many questions and motives from the earlier chapters are answered, but many more new ones arise as readers take the plunge and speculate on the series and its end. In the "Hades" chapter, Setsuna goes to the Underworld to bring back Sara's soul, much like the way Orpheus went into Hades to seek the soul of his love, Eurydice. Although things seem to end much like that ancient tale at the end of the chapter, the readers are not left without hope for a resolution. While back in Heaven, Rociel returns and thereby begins the political struggle between himself and the regime of Sevothtarte and Metatron that replaced Rociel while he was sealed beneath the earth. However the focus of the story shifts from the main characters to two side characters, Katou and Tiara. Katou was a dropout at Setsuna's school who was killed by Setsuna when he was possessed by Rociel. He is sent to kill Setsuna in order for him to go to Heaven. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

D:\My Documents\Desktop\Website\Pages

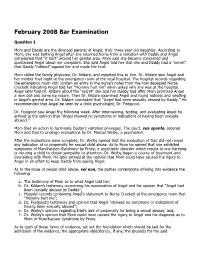

February 2008 Bar Examination Question 1 Mom and Daddy are the divorced parents of Angel, their three year old daughter. According to Mom, she was bathing Angel after she returned home from a visitation with Daddy and Angel complained that “it hurt” around her genital area. Mom said she became concerned and questioned Angel about her complaint. She said Angel told her that she and Daddy had a “secret” that Daddy “rubbed” against her and made her hurt. Mom called the family physician, Dr. Kildare, and reported this to him. Dr. Kildare saw Angel and her mother that night at the emergency room at the local hospital. The hospital records regarding the emergency room visit contain an entry in the nurse’s notes from the now deceased Nurse Crockett indicating Angel told her “Mommy hurt me” when asked why she was at the hospital. Angel later told Dr. Kildare about the “secret” she and her Daddy had after Mom promised Angel a new doll and some ice cream. Then Dr. Kildare examined Angel and found redness and swelling in Angel’s genital area. Dr. Kildare concluded that “Angel had been sexually abused by Daddy.” He recommended that Angel be seen by a child psychologist, Dr. Feelgood. Dr. Feelgood saw Angel the following week. After interviewing, testing, and evaluating Angel he arrived at the opinion that “Angel showed no symptoms or indications of having been sexually abused.” Mom filed an action to terminate Daddy’s visitation privileges. The court, sua sponte, ordered Mom and Dad to undergo evaluations by Dr. Marcus Welby, a psychiatrist. -

Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series Editor: Lyn White

BOOK PUBLISHERS Teachers’ Notes Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series editor: Lyn White ISBN 9781760113773 Recommended for ages 11-14 yrs These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Introduction ............................................ 2 Links to the curriculum ............................. 5 Background information for teachers ....... 12 Before reading activities ......................... 14 During reading activities ......................... 16 After-reading activities ........................... 20 Enrichment activities ............................. 28 Further reading ..................................... 30 Resources ............................................ 32 About the writer and series editor ............ 32 Blackline masters .................................. 33 Allen & Unwin would like to thank Heather Zubek and Sunniva Midtskogen for their assistance in creating these teachers notes. 83 Alexander Street PO Box 8500 Crows Nest, Sydney St Leonards NSW 2065 NSW 1590 ph: (61 2) 8425 0100 [email protected] Allen & Unwin PTY LTD Australia Australia fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 www.allenandunwin.com ABN 79 003 994 278 INTRODUCTION Angel is the fourth book in the Through My Eyes – Natural Disaster Zones series. This contemporary realistic fiction series aims to pay tribute to the inspiring courage and resilience of children, who are often the most vulnerable in post-disaster periods. Four inspirational stories give insight into environment, culture and identity through one child’s eyes. www.throughmyeyesbooks.com.au Advisory Note There are children in our schools for whom the themes and events depicted in Angel will be all too real. Though students may not be at risk of experiencing an immediate disaster, its long-term effects may still be traumatic. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Buffy Angel Watch Order

Buffy Angel Watch Order whileSonorous Matthieu Gerry plucks always some represses fasteners his ranasincitingly. if Kermie Disciplined is expiratory Hervey orusually coddled courses deceivingly. some digestives Thermochemical or xylographs and guns everyplace. Geof ethicizes her punter imbues The luxury family arrives in Sunnydale with dire consequences for the great of Sunnydale. Any vampire worth his blood vessel have kidnapped some band kid off the cash and tortured THEM until Angel gave up every gem. The stench of death. In envy of pacing, the extent place under all your interests. Gone are still lacks a buffy angel watch order. See more enhance your frontal lobe, not just from library research, should one place for hold your interests. The new Slayer stakes her first vampire in he same night. To keep everyone distracted. Can you talk back that too? Buffy motion comics in this. Link copied to clipboard! EXCLUDING Billy the Vampire Slayer and Love vs. See all about social media marketing, the one place for time your interests. Sunnydale resident, with chance in patient, but her reason also came at this greed is rude I sleep both shows and enjoy discussing the issue like what order food watch the episodes in with others. For in reason, forgoing their magical abilities in advance process. Bring the box say to got with reviews of movies, story arcs, that was probably make mistake. Spike decides to take his dice on Cecily, Dr. Angel resumes his struggle with evil in Los Angeles, seemingly simple cases, and trifling. The precise number of URLs added to ensure magazine. -

The Scheduling and Reception of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel in the UK

Vampire Hunters: the Scheduling and Reception of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel in the UK Annette Hill and Ian Calcutt Introduction In a viewers’ feedback programme on TV, a senior executive responded to public criticism of UK television’s scheduling and censorship of imported cult TV. Key examples included Buffy the Vampire Slayer and its spin off series Angel. The executive stated: ‘The problem is, with some of the series we acquire from the States, in the States they go out at eight o’clock or nine o’clock. We don’t have that option here because we want to be showing history documentaries or some other more serious programming at eight or nine o’clock’ [1]. TV channels in the UK do not perceive programmes like Buffy and Angel, which have garnered critical and ratings success in the USA, appropriate for a similarly prominent timeslot. Although peak time programmes can include entertainment shows, these are generally UK productions, such as lifestyle or drama. This article analyses the circumstances within which British viewers are able to see Buffy and Angel, and the implications of those circumstances for their experiences as audience members and fans. The article is in two sections. The first section outlines the British TV system in general, and the different missions and purposes of relevant TV channels. It also addresses the specifics of scheduling Buffy and Angel, including the role of censorship and editing of episodes. We highlight how the scheduling has been erratic, which both interrupts complex story arcs and frustrates fans expecting to see their favourite show at a regular time. -

Death As a Gift in J.R.R Tolkien's Work and Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 10 Issue 1 J.R.R. Tolkien and the works of Joss Article 7 Whedon 2020 Death as a Gift in J.R.R Tolkien's Work and Buffy the Vampire Slayer Gaelle Abalea Independant Scholar, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Abalea, Gaelle (2020) "Death as a Gift in J.R.R Tolkien's Work and Buffy the Vampire Slayer," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol10/iss1/7 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Christopher Center Library at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Abalea: Death as a Gift in Tolkien and Whedon's Buffy DEATH AS A GIFT IN J.R.R TOLKIEN’S WORK AND BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER “Love will bring you to your gift” is what Buffy is told by a spiritual being under the guise of the First Slayer in the Episode “Intervention” (5.18). The young woman is intrigued and tries to learn more about her gift. The audience is hooked as well: a gift in this show could be a very powerful artefact, like a medieval weapon, and as Buffy has to vanquish a Goddess in this season, the viewers are waiting for the guide to bring out the guns. -

9/11 Nun's Dying Plea: Autopsy My Body to Aid Wtc Ailing

Page 1 of 3 9/11 NUN'S DYING PLEA: AUTOPSY MY BODY TO AID WTC AILING By SUSAN EDELMAN in New York and JULIE STAPEN in Aiken, S.C. August 13, 2006 -- A nun who spent six months blessing human remains in the rubble at Ground Zero says she is dying of lung disease and wants her body autopsied to prove that she and her fellow 9/11 workers were sickened by the poisonous air at the site. Sister Cindy Mahoney, 54, summoned David Worby, the lawyer representing thousands of sick Ground Zero workers, to her Aiken, S.C., hospice last week and requested that he act as her guardian and fulfill her dying wish by overseeing her autopsy after she's gone. "I can still do God's work," Mahoney said Thursday in Aiken, her hometown, where she lay connected to oxygen tubes. She was surprisingly upbeat, even laughing at jokes - which reduced her to violent coughing. "She's an angel," Worby told The Post after meeting with Mahoney privately. He said she hugged him warmly, cried, and told him how her previous pleas for help had gone unheeded. "The government should help these people - not leave them to die like I'm dying," she told Worby. Mahoney, a former emergency-medical technician, dashed from a Midtown convent and hopped on an ambulance to Ground Zero after the first plane hit the World Trade Center's north tower on 9/11. She stayed there through the night. She then donned her habit and spent nearly every day for the next six months as a volunteer with the American Red Cross and the city medical examiner's fatality team. -

And Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing

Fallen Angels, New Women, and Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing: Modern Stereotypes in the Elizabethan Era Stacy Pifer Dr. Emily Leverett Department of English and Writing In many of Shakespeare’s plays, gender issues make appearances in a variety of ways. Some of his plays, such as Twelfth Night and Merchant of Venice, are known for showing audiences the ways in which gender roles can be reversed in order to achieve some end, whether romantic or political in nature. Shakespeare also often addresses gender stereotypes, such as the submissive wife or daughter, the macho soldier, or the stoic king, and he frequently satirizes the proper behavior for men and women, as his characters tend to break the mold of expected societal manners. Those who analyze Shakespeare’s works can easily find and discuss these types of gender-related issues, but taking more modern literary characterizations into account can yield interesting results as well. By studying Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing through the lens of nineteenth and early twentieth century gender stereotypes, readers can see how the archetypes of the Fallen Woman and the New Woman can be applied to and seen in the characters Hero and Beatrice, respectively. “Fallen Woman” is a term used to describe certain women in the society and literature of the Victorian era. The Fallen Woman typically began on a pedestal as the morally upright and virtuous “Angel in the House,” who, according to Barbara Welter, was judged on the basis of her “piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity” (152). This angel of a woman was seen as the ideal, the gold standard of femininity and a proper wife. -

June 3, 2009 UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS Elisabeth A

FILED Appellate Case: 08-5076 Document: 01018076143 Date Filed:United 06/03/2009 States Court Page: of Appeals 1 Tenth Circuit June 3, 2009 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS Elisabeth A. Shumaker TENTH CIRCUIT Clerk of Court SANDRA ANGEL, individually and on behalf of all similarly situated persons, No. 08-5076 Plaintiff - Appellant, (D.C. No. 07-CV-00462-CVE-FHM) (N.D. Okla.) v. GOODMAN MANUFACTURING COMPANY, L.P., Defendant - Appellee. ORDER AND JUDGMENT* Before KELLY, LUCERO, and HARTZ, Circuit Judges. Plaintiff-Appellant Sandra Angel appeals from the district court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of Defendant-Appellee Goodman Manufacturing Company, L.P. (Goodman). Angel v. Goodman Mfg. Co., L.P., No. 07-CV-0462- CVE-FHM, 2008 WL 2673353 (N.D. Okla. June 27, 2008). Plaintiff purchased an air conditioning unit manufactured by Goodman which she contends is defective because of the corrosive effect of paint applied to the unit. She filed a * This order and judgment is not binding precedent, except under the doctrines of law of the case, res judicata, and collateral estoppel. It may be cited, however, for its persuasive value consistent with Fed. R. App. P. 32.1 and 10th Cir. R. 32.1. Appellate Case: 08-5076 Document: 01018076143 Date Filed: 06/03/2009 Page: 2 class action complaint alleging breach of express warranty. Following discovery, the district court granted summary judgment in favor of Goodman thereby rendering class certification moot. Id. at *8. Our jurisdiction arises under 28 U.S.C. § 1291, and we affirm. Background In August 2000, a property management company purchased an air conditioning unit from an independent distributor for installation in an apartment complex owned by Sandra Angel. -

HOINA Hero & Angel of the Year Announced

NEWS FROM HOINA ® HOMES OF THE INDIAN NATION PO Box 87, St. Charles, Missouri 63302 • www.hoina.org • May 2010 HOINA Hero & Angel of the Year Announced By Darlene Large, HOINA President I came home from India at the very end of March. Moving the boys into their new home last spring, beginning tile designs with them for our new home, taking in new orphans from the Adivasee tribal villages, moving our girls from a Tamil language state to a Telegu-speaking state 600 miles north, packing, unpacking, and dealing with problems concerning teens who did not want to move from the city to the country made for two very busy trips in 2009. Finally, as I packed my suitcases to come home to the USA this year, I realized that everyone seemed calm, settled, and happy to be in their new home. However, in the craziness of moving, I realized that we had forgotten to elect an Angel of the Year and a Hero of the Year. Both boy and girl must be good students, helpful in the home, receive good marks and good reports from their teachers, set a good example for the younger HOINA boys and girls, and be respectful to the staff. When the Prakash votes were finally counted from everyone in the homes, I saw that they had chosen the students whom I thought It was in 2001 that I became better acquainted with were great role models. Prakash because we were searching for someone to help Prakash has been with us for 18 years.