And Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unmatched: Buffy the Vampire Slayer Rulebook

RULES THE UNMATCHED SYSTEM Unmatched is a miniatures dueling game featuring fighters of all kinds — from the page to the screen to the stuff of legends. Each hero has a unique deck of cards that fits their fighting style. You can mix and match fighters from 03 any Unmatched set. But remember, in the end, there can only be one winner. All of your characters in the battle are HEROES& called your fighters, but your primary CONTENTS fighter is called your hero. Heroes are represented by miniatures that move SIDEKICKS around on the battlefield. 3 BUFFY Your other fighters are called sidekicks. All of the heroes RAPID RECOVERY in this set have a single sidekick. (Some heroes in other sets 3 AFTER COMBAT: ACTION CARDS ACTION 1 health. Buffy recovers have multiple sidekicks, and still other heroes have no sidekick HERO MINIATURES HEALTH DIALS HEALTH BUFFY 25 | x3 4 1 8 at all.) Sidekicks are represented by tokens that move around on the battlefield. HERO BUFFY MELEE ATTACK Each hero has a special ability noted on their character card. START 14 HEALTH Buffy may move through spaces containing opposing This card also lists your fighters’ stats, including the starting fighters (including when 3 she is moved by effects). health of your hero and their sidekick. Fighters’ health is SPECIAL ABILITY ™ & © 20th Century Fox BATTLEFIELDS MOVE 2 SIDEKICK GILES OR XANDER tracked on separate health dials. Fighters cannot gain health CHARACTER CARDS CHARACTER MELEE SIDEKICK TOKENS ATTACK START 6 HEALTH DOUBLE-SIDED BOARD DOUBLE-SIDED 4 4 1 WITH higher than the highest number on their health dial. -

Angel Sanctuary, a Continuation…

Angel Sanctuary, A Continuation… Written by Minako Takahashi Angel Sanctuary, a series about the end of the world by Yuki Kaori, has entered the Setsuna final chapter. It is appropriately titled "Heaven" in the recent issue of Hana to Yume. However, what makes Angel Sanctuary unique from other end-of-the-world genre stories is that it does not have a clear-cut distinction between good and evil. It also displays a variety of worldviews with a distinct and unique cast of characters that, for fans of Yuki Kaori, are quintessential Yuki Kaori characters. With the beginning of the new chapter, many questions and motives from the earlier chapters are answered, but many more new ones arise as readers take the plunge and speculate on the series and its end. In the "Hades" chapter, Setsuna goes to the Underworld to bring back Sara's soul, much like the way Orpheus went into Hades to seek the soul of his love, Eurydice. Although things seem to end much like that ancient tale at the end of the chapter, the readers are not left without hope for a resolution. While back in Heaven, Rociel returns and thereby begins the political struggle between himself and the regime of Sevothtarte and Metatron that replaced Rociel while he was sealed beneath the earth. However the focus of the story shifts from the main characters to two side characters, Katou and Tiara. Katou was a dropout at Setsuna's school who was killed by Setsuna when he was possessed by Rociel. He is sent to kill Setsuna in order for him to go to Heaven. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

“My” Hero Or Epic Fail? Torchwood As Transnational Telefantasy

“My” Hero or Epic Fail? Torchwood as Transnational Telefantasy Melissa Beattie1 Recibido: 2016-09-19 Aprobado por pares: 2017-02-17 Enviado a pares: 2016-09-19 Aceptado: 2017-03-23 DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo Beattie, M. (2017). “My” hero or epic fail? Torchwood as transnational telefantasy. Palabra Clave, 20(3), 722-762. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Abstract Telefantasy series Torchwood (2006–2011, multiple production partners) was industrially and paratextually positioned as being Welsh, despite its frequent status as an international co-production. When, for series 4 (sub- titled Miracle Day, much as the miniseries produced as series 3 was subti- tled Children of Earth), the production (and diegesis) moved primarily to the United States as a co-production between BBC Worldwide and Amer- ican premium cable broadcaster Starz, fan response was negative from the announcement, with the series being termed Americanised in popular and academic discourse. This study, drawn from my doctoral research, which interrogates all of these assumptions via textual, industrial/contextual and audience analysis focusing upon ideological, aesthetic and interpretations of national identity representation, focuses upon the interactions between fan cultural capital and national cultural capital and how those interactions impact others of the myriad of reasons why the (re)glocalisation failed. It finds that, in part due to the competing public service and commercial ide- ologies of the BBC, Torchwood was a glocalised text from the beginning, de- spite its positioning as Welsh, which then became glocalised again in series 4. -

City Officials from Across the State Named “Home Rule Heroes”

301 S. Bronough Street, Suite 300 ● Post Office Box 1757 ● Tallahassee, FL 32302-1757 (850) 222-9684 ● Fax: (850) 222-3806 ● Website: flcities.com City Officials from Across the State Named “Home Rule Heroes” The Florida League of Cities recognizes local officials for their advocacy efforts during legislative session FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 9, 2019 CONTACT: Brittni Johnsen [email protected] / (850) 701-3652 The Florida League of Cities is recognizing more than 100 municipal officials with Home Rule Hero Awards for their work during the 2019 legislative session. These local leaders earned this award for their tireless efforts to protect the Home Rule powers of Florida’s municipalities and advance the League’s legislative agenda. “The dedication and effort of these local officials during the 2019 legislative session was extraordinary,” said FLC Legislative Director Scott Dudley. “These are some of our biggest advocates for municipal issues, and they’re shining examples of local advocacy in action. On behalf of the League and its legislative team, we’re proud to recognize each and every one of them and thank them for their service.” Home Rule is the ability for a city to address local problems with local solutions with minimal state interference. Home Rule Hero Award recipients are local government officials, both elected and nonelected, who consistently responded to the League’s request to reach out to members of the legislature and help give a local perspective to an issue. The 2019 Home Rule Hero Award recipients are: City Title Name City of Altamonte Springs Mayor Pat Bates City of Arcadia Councilmember Judy Wertz-Strickland City of Atlantic Beach Mayor Ellen Glasser City of Bartow Commissioner Leo E. -

A Fantasy Subverting the Woman‟S Image As “The Angel in the House”

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 4, No. 10, pp. 2061-2065, October 2014 © 2014 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.4.10.2061-2065 A Fantasy Subverting the Woman‟s Image as “The Angel in the House” Aihong Ren School of Foreign Languages, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, Shandong, China Abstract—In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll creates a subversive fantasy of females seeking autonomy and independence by means of the fantastic mode. The female characters in the underground include the Duchess, the Cook, the Queen of Red Hearts and Alice. They all display clear features which are atypical of the popular ideal woman image of the Victorian society---“the angel in the house”, like obedience, self-sacrifice, passiveness and gentleness. On the contrary, those adult females show madness and violence in their separate roles, while Alice the little girl displays autonomy, independence and aggression in her fantasy quest. By subverting the ideal woman image, Carroll gives expression to the repressed feelings of the woman in his society. Index Terms—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the angel in the house, Alice, gender role I. INTRODUCTION “The Angel in the House” is the popular Victorian image of the ideal wife/woman. The phrase comes from the title of an immensely popular poem by Coventry Patmore, in which he holds his angel-wife up as a model for all women. Though the poem did not receive much attention when first published in 1854, it became increasingly popular through the rest of the nineteenth century and continued to be influential in the twentieth century. -

D:\My Documents\Desktop\Website\Pages

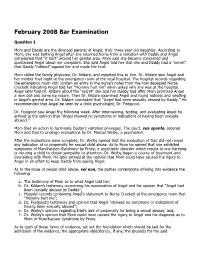

February 2008 Bar Examination Question 1 Mom and Daddy are the divorced parents of Angel, their three year old daughter. According to Mom, she was bathing Angel after she returned home from a visitation with Daddy and Angel complained that “it hurt” around her genital area. Mom said she became concerned and questioned Angel about her complaint. She said Angel told her that she and Daddy had a “secret” that Daddy “rubbed” against her and made her hurt. Mom called the family physician, Dr. Kildare, and reported this to him. Dr. Kildare saw Angel and her mother that night at the emergency room at the local hospital. The hospital records regarding the emergency room visit contain an entry in the nurse’s notes from the now deceased Nurse Crockett indicating Angel told her “Mommy hurt me” when asked why she was at the hospital. Angel later told Dr. Kildare about the “secret” she and her Daddy had after Mom promised Angel a new doll and some ice cream. Then Dr. Kildare examined Angel and found redness and swelling in Angel’s genital area. Dr. Kildare concluded that “Angel had been sexually abused by Daddy.” He recommended that Angel be seen by a child psychologist, Dr. Feelgood. Dr. Feelgood saw Angel the following week. After interviewing, testing, and evaluating Angel he arrived at the opinion that “Angel showed no symptoms or indications of having been sexually abused.” Mom filed an action to terminate Daddy’s visitation privileges. The court, sua sponte, ordered Mom and Dad to undergo evaluations by Dr. Marcus Welby, a psychiatrist. -

Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series Editor: Lyn White

BOOK PUBLISHERS Teachers’ Notes Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series editor: Lyn White ISBN 9781760113773 Recommended for ages 11-14 yrs These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Introduction ............................................ 2 Links to the curriculum ............................. 5 Background information for teachers ....... 12 Before reading activities ......................... 14 During reading activities ......................... 16 After-reading activities ........................... 20 Enrichment activities ............................. 28 Further reading ..................................... 30 Resources ............................................ 32 About the writer and series editor ............ 32 Blackline masters .................................. 33 Allen & Unwin would like to thank Heather Zubek and Sunniva Midtskogen for their assistance in creating these teachers notes. 83 Alexander Street PO Box 8500 Crows Nest, Sydney St Leonards NSW 2065 NSW 1590 ph: (61 2) 8425 0100 [email protected] Allen & Unwin PTY LTD Australia Australia fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 www.allenandunwin.com ABN 79 003 994 278 INTRODUCTION Angel is the fourth book in the Through My Eyes – Natural Disaster Zones series. This contemporary realistic fiction series aims to pay tribute to the inspiring courage and resilience of children, who are often the most vulnerable in post-disaster periods. Four inspirational stories give insight into environment, culture and identity through one child’s eyes. www.throughmyeyesbooks.com.au Advisory Note There are children in our schools for whom the themes and events depicted in Angel will be all too real. Though students may not be at risk of experiencing an immediate disaster, its long-term effects may still be traumatic. -

Much Ado About Nothing, by William Shakespeare

Much Ado About Nothing, by William Shakespeare In A Nutshell Much Ado About Nothing is one of William Shakespeare’s best-loved comedies. Written around 1598, the play is about a young woman wrongly accused of being unchaste who is later reconciled with her accusing lover. It is also about a second couple – two witty, bright individuals who swear they will never fall in love. Stories about young women wrongly accused, brought close to death, and then rejoined with their lovers were really popular during the Renaissance. Shakespeare used that trope (which can be traced all the way back to the Greek romances) to make this light and silly comedy. The play trips along at a steady place as characters invent and pass on totally misleading information; watching this process as it undoes characters is like playing a 16th century game of Telephone. This is a neat chance to watch Shakespeare shake a complex (sometimes unnecessarily complex) plot. Further, it’s a cool "study in progress" of Shakespeare: Beatrice and Benedick’s acidic romance is a more developed version of the hatred-turned-to-love from The Taming of the Shrew; and Don John, the inexplicably evil villain of this play, is a sort of character study for the inexplicably evil Iago of Shakespeare’s later play Othello. Visit Shmoop for much more analysis: • Much Ado About Nothing Themes • Much Ado About Nothing Quotes Visit Shmoop for full coverage of Much Ado About Nothing Shmoop: study guides and teaching resources for literature, US history, and poetry Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 This document may be modified and republished for noncommercial use only. -

Erich Korngold Was One of History's Most

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Much Ado About Nothing Suite, Op. 11 Erich Korngold rich Korngold was one of history’s most was produced to astonished acclaim at the Eextraordinary prodigies, rivaled in the an - Vienna Court Opera. By then he had already nals of child composers only by Felix completed his Piano Trio (Op. 1) and he Mendelssohn and (arguably) Mozart. He was would momentarily finish his Piano Sonata born into a musical family: his father, Julius No. 2, which the pianist Artur Schnabel im - Korngold, was a noted music critic who be - mediately put into his concert repertoire. friended and then succeeded Eduard Two years later Korngold produced his Hanslick on the staff of Vienna’s Neue Freie Sonata for Violin and Piano; again, it was Presse . Music came naturally to him. His Schnabel who took up its cause, program - mother, asked later in life about when her ming it in joint recitals with the eminent vio - son began playing the piano, replied, “Erich linist Carl Flesch. Composers all over Europe always played the piano.” In fact, he never were awed by their young colleague: Richard had more than basic training on the instru - Strauss, Giacomo Puccini, Jean Sibelius, and ment (curiously, since his father could have many others scrambled for superlatives to opened doors to the most renowned studios describe what they heard. By the time Korn - in Vienna), but it’s not clear that regimented gold was 20 his orchestral works had been study would have improved what already played by the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra seemed to be absolute fluency at the key - (Arthur Nikisch conducting) and the Vienna board. -

Much Ado About Nothing” – Lecture/Class

“REVENGE IN SHAKESPEARE’S PLAYS” “MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING” – LECTURE/CLASS WRITTEN: In the second half of 1598 or 99 -- no later because the role of Dogberry was sometimes replaced by the name of “Will Kemp”, the actor who always played the role; Kemp left the Lord Chamberlain’s Men in 1599. AGE: 34-35 Years Old (B.1564-D.1616) CHRONO: Seventh in the line of Comedies after “The Two Gentlemen of Verona”, “The Comedy of Errors”, “Taming of the Shrew”, “Love’s Labours Lost”, “A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream”, “The Merchant of Venice”. QUARTO: A Quarto edition of the play appeared in 1600. GENRE: “Tragicomic” SOURCE: “Completely and entirely unhistorical” VERSION: The play is “Shakespeare’s earliest version of the more serious story of the man who mistakenly believes his partner has been unfaithful to him”. (“Othello” for one.) SUCCESS: There are no records of early performances but there are “allusions to its success.” HIGHLIGHT: The comedy was revived in 1613 for a Court performance at Whitehall before King James, his daughter Princess Elizabeth and her new husband in May 1613. AFTER: Oddly, the play was “performed only sporadically until David Garrick’s acclaimed revival in 1748”. CRITICS: 1891 – A.B. Walkley: “a composite picture of the multifarious, seething, fermenting life, the polychromatic phantasmagoria of the Renaissance.” 1905 – George Bernard Shaw: “a hopeless story, pleasing only to lovers of the illustrated police papers BENEDICTS: Anthony Quayle, John Gielgud, Michael Redgrave, Donald Sinden BEATRICES: Peggy Ashcroft, Margaret Leighton, Judi Dench, Maggie Smith RECENT: There was “a boost in recent fortunes with the well-received 1993 film version directed by Kenneth Branagh and starring Branagh and Emma Thompson.” SETTING: Messina in northeastern Sicily at the narrow strait separating Sicily from Italy. -

'Bite Me': Buffy and the Penetration of the Gendered Warrior-Hero

Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2002 ‘Bite Me’: Buffy and the penetration of the gendered warrior-hero SARA BUTTSWORTH, University of Western Australia Introduction Can the ultimate girl be the ultimate warrior? If warrior identity is simultaneously a quintessentially masculine identi er, and one of the core expressions of ‘innate’ masculinity, then the biggest transgression of warrior iconography posed by Buffy the Vampire Slayer is Buffy’s gender. Buffy is both like and not like ‘other girls’. The social conventions of mainstream femininity, which have so often been used to argue that women cannot be warriors, are often precisely what make Buffy such an effective soldier in her speculative world. The blurred boundaries that are possible in speculative texts open up space necessary to examine the arguments and gendered ideologies which govern what is, and what is not, possible in the ‘real’ world. Such texts can often make explicit what is implied in more ‘realistic’ representations, and can either destabilize or reinforce gendered cultural conventions.1 Established as the ‘chosen one’ in the 1992 lm, and then in the television series which debuted mid-season in 1997, Buffy has slashed her way not only through the ctional constraints placed upon her predecessors in vampire carnage, but through the conventions governing gendered constructions of the warrior.2 Warrior tradition con- structs a coherent masculinity, including impenetrable male bodies, as the key to warrior identity, and renders ‘slay-gal’3 not only paradoxical but, arguably, impossible. It is this (im)possibility, and the ways in which Buffy the Vampire Slayer fractures and reinvents the gendered identity of the warrior-hero, which are explored in this article.