An Afrocentric Analysis of Hip-Hop Musical Art Composition and Production: Roles, Themes, Techniques, and Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

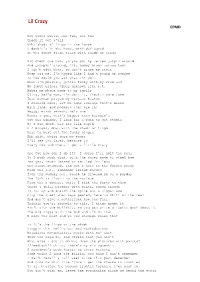

EPMD Lil Crazy

Lil Crazy EPMD Hey young world, one two, one two Check it out y'all Uhh, shadz of lingo in the house E double's in the house with def squad On the funky fresh track with shadz of lingo Mic check one two, yo you got my nerves jumpin around And _humpin' around_ like bobby brown across town I ain't with that, so don't cramp my style Step off me, I'm hyped like I had a pound of coffee Yo how could you ask what I'm doin When I'm pursuin, gettin funky with my crew and My input brings vibes unknown like e.t. Makes me phone home to my family Cling, hello mom, I'm doin it, freakin more fame Than batman played by michael keaton I crossed over, let me name someone that's black With fame, and pockets that are fat Heyyy, erick sermon, he's one Packs a gun, that's bigger than malcolm's Out the window, I look for a punk to get stupid So I can shoot his ass like cupid E 2 bingos, down with the shadz of lingo Here to bust out the funky single Ahh shit, there goes my pager I'll see you later, because yo Every now and then, I get a little crazy One two how can I do it? I guess I'll spit the real Yo I pack much dick, with the cover made of steel hoe Yes yes, never fessed or settled for less One clown stepped, and got a hole in the fuckin chest From the a.k., somebody scream mayday Took the sucker out, cause he clowned me on a payday The funk is flowin to the maximum From the e double, while I kick the facts to them Check a chill brother with class, rough enough To run up and snatch the spine out a niggaz ass Grip the steel when caps peeled, here to chill -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Kaya Hip-Hop in Coastal Kenya: the Urban Poetry of UKOO FLANI

Page 1 of 46 Kaya Hip-Hop in Coastal Kenya: The Urban Poetry of UKOO FLANI By: Divinity LaShelle Barkley [email protected] Academic Director: Athman Lali Omar I.S.P. Advisor: Professor Mohamed Abdulaziz S.I.T. Kenya, Fall 2007 Coastal Cultures & Swahili Studies Kaya Hip Hop in Coastal Kenya Fall 2007 ISP, SIT Kenya By: Divinity L. Barkley Page 2 of 46 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………..………………….page 3 Abstract……………………………………………..…………………………page 4 Introduction…………………………………..……………………………pages 5-8 Hip-Hop & Kenyan Youth Culture Research Problem Status of Hip-Hop in Kenya Hypotheses The Setting……………………………….………………………………pages 9-10 Methodology: Data Collection……………………………………..…pages 10-12 Biases and Assumptions………………………..………...…………...pages 13-14 Discussion & Analysis…………………………………………………pages 14-38 Ukoo Flani ni nani? Kaya Hip-Hop Traditional Role of Music in African Culture Genesis of Rap/Hip-hop in American Ghettoes The Ties That Bind Kenyan Radio The Maskani Ghetto Life Will the real Ukoo Flani please stand up? Urban Poetry: Analyzing Ukoo Flani’s Lyrics Conclusion…………………………..……………………….…………pages 38-42 Conclusion Part I: The Future of Ukoo Flani Conclusion Part II: Hypotheses Results Conclusion Part III: Recommendations for Future SIT Students Bibliography………………………………………………..…………..pages 43-44 Interview/Meeting Schedule………………………………………………page 45 ISP Review Sheet…………….……………………………………….……page 46 Kaya Hip Hop in Coastal Kenya Fall 2007 ISP, SIT Kenya By: Divinity L. Barkley Page 3 of 46 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank the entire Ukoo Flani crew for their contributions to my project. I am fascinated by your amazing talent and dedication to making positive music to inspire future generations. I am amazed at what you have been able to accomplish despite limited access to resources. -

Gender Dimensions in Emerging African Music Genres: a Case of Kenyan Local Hip Hop

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 24, Issue 5, Ser. 9 (May. 2019) 54-61 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Gender Dimensions in Emerging African Music Genres: A Case of Kenyan Local Hip Hop Pamela N.Wanjala Shamberere Technical Training Institute P.o Box 1316, Kakamega, Kenya Abstract: The question of gender bias is now seen as a major challenge in almost every discipline that deals with human behavior, cognition, institutions, society and culture. Therefore, this paper was an attempt to investigate gender dimensions in the emerging African genres; a case study of local hip hop songs in Kenya. It discussed the extent to which hip hop language is gender biased. It focused on the popular local hip hop songs and video images that occur with the songs. The study used the Social Semiotic Theory in the theoretical framework. Ten hip hop songs and ten video excerpts were purposively selected for analysis. The hip hop songs were coded according to the name of the artist and year of production. The data was analyzed under three sections: Linguistic analysis, Image analysis and Gender analysis. The study revealed that indeed there is gender bias in the language of the favourite youth culture. This was revealed in the lexis that distinguishes gender, in the syntactic analysis and also in the image analysis. It was found that in hip hop music, men tend to be regarded higher in terms of roles, occupation and general human traits like strength and control than women. The study therefore recommends that radio and television stations, and other advertising agencies should join the battle for women liberation by using gender sensitive language and focusing on positive and constructive societal changes in terms of gender roles. -

Is Hip Hop Dead?

IS HIP HOP DEAD? IS HIP HOP DEAD? THE PAST,PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF AMERICA’S MOST WANTED MUSIC Mickey Hess Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Mickey, 1975- Is hip hop dead? : the past, present, and future of America’s most wanted music / Mickey Hess. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 (alk. paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3531H47 2007 782.421649—dc22 2007020658 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007020658 ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 ISBN-10: 0-275-99461-9 First published in 2007 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 1THE RAP CAREER 13 2THE RAP LIFE 43 3THE RAP PERSONA 69 4SAMPLING AND STEALING 89 5WHITE RAPPERS 109 6HIP HOP,WHITENESS, AND PARODY 135 CONCLUSION 159 NOTES 167 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 INDEX 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of a Rider University Summer Fellowship helped me com- plete this book. I want to thank my colleagues in the Rider University English Department for their support of my work. -

Global Hip-Hop Class

AAAS 135b: GLOBAL HIP-HOP Wed 6:30-9:20 pm Mandel G03 Spring 2012 Wayne Marshall [email protected] office hours: by appointment DESCRIPTION Examining how hip-hop travels and is embraced, represented, and transformed in various locales around the world, this course approaches hip-hop as itself constituted by international flows and as a product and set of practices that circulate globally in complex ways, cast variously as American, African-American, and/or black, and recast through the cultural logics of the new spaces it enters, the soundscapes it permeates. A host of questions arise when we consider hip-hopʼs global scope and significance: What does the genre in its various forms (audio, video, sartorial, gestural) carry beyond the US? What do people bring to it in new local contexts? How are US notions of race and nation mediated by hip-hop's global reach? Why do some global (which is to say, local) hip-hop scenes fasten onto the genre's well-rehearsed focus on place, community, and righteous opposition to structural and representational forms of violence, while others appear more enamored with slick portrayals of hustler archetypes, cool machismo, and ruggedly individualist, conspicuous consumption? How can hip-hop circulate in such contradictory forms? In what ways do hip-hop scenes differ from North to South America, West to East Africa, Europe to Asia? What threads unite them? In pursuit of such questions, we will read across the emerging literature on global hip- hop as we explore the growing resources available via the internet, where websites and blogs, MySpace and YouTube and the like have facilitated a further efflorescence of international (and peer-to-peer) exchanges around hip-hop. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Tom Jennings

12 | VARIANT 30 | WINTER 2007 Rebel Poets Reloaded Tom Jennings On April 4th this year, nationally-syndicated Notes US radio shock-jock Don Imus had a good laugh 1. Despite the plague of reactionary cockroaches crawling trading misogynist racial slurs about the Rutgers from the woodwork in his support – see the detailed University women’s basketball team – par for the account of the affair given by Ishmael Reed, ‘Imus Said Publicly What Many Media Elites Say Privately: How course, perhaps, for such malicious specimens paid Imus’ Media Collaborators Almost Rescued Their Chief’, to foster ratings through prejudicial hatred at the CounterPunch, 24 April, 2007. expense of the powerless and anyone to the left of 2. Not quite explicitly ‘by any means necessary’, though Genghis Khan. This time, though, a massive outcry censorship was obviously a subtext; whereas dealing spearheaded by the lofty liberal guardians of with the material conditions of dispossessed groups public taste left him fired a week later by CBS.1 So whose cultures include such forms of expression was not – as in the regular UK correlations between youth far, so Jade Goody – except that Imus’ whinge that music and crime in misguided but ominous anti-sociality he only parroted the language and attitudes of bandwagons. Adisa Banjoko succinctly highlights the commercial rap music was taken up and validated perspectival chasm between the US civil rights and by all sides of the argument. In a twinkle of the hip-hop generations, dismissing the focus on the use of language in ‘NAACP: Is That All You Got?’ (www.daveyd. -

NTOZAKE SHANGE, JAMILA WOODS, and NITTY SCOTT by Rachel O

THEORIZING BLACK WOMANHOOD IN ART: NTOZAKE SHANGE, JAMILA WOODS, AND NITTY SCOTT by Rachel O. Smith A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English West Lafayette, Indiana May 2020 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. Marlo David, Chair Department of English Dr. Aparajita Sagar Department of English Dr. Paul Ryan Schneider Department of English Approved by: Dr. Dorsey Armstrong 2 This thesis is dedicated to my mother, Carol Jirik, who may not always understand why I do this work, but who supports me and loves me unconditionally anyway. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to first thank Dr. Marlo David for her guidance and validation throughout this process. Her feedback has pushed me to investigate these ideas with more clarity and direction than I initially thought possible, and her mentorship throughout this first step in my graduate career has been invaluable. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Aparajita Sagar and Dr. Ryan Schneider, for helping me polish this piece of writing and for supporting me throughout this two-year program as I prepared to write this by participating in their seminars and working with them to prepare conference materials. Without these three individuals I would not have the confidence that I now have to continue on in my academic career. Additionally, I would like to thank my friends in the English Department at Purdue University and my friends back home in Minnesota who listened to my jumbled thoughts about popular culture and Black womanhood and asked me challenging questions that helped me to shape the argument that appears in this document. -

Turntablism and Audio Art Study 2009

TURNTABLISM AND AUDIO ART STUDY 2009 May 2009 Radio Policy Broadcasting Directorate CRTC Catalogue No. BC92-71/2009E-PDF ISBN # 978-1-100-13186-3 Contents SUMMARY 1 HISTORY 1.1-Defintion: Turntablism 1.2-A Brief History of DJ Mixing 1.3-Evolution to Turntablism 1.4-Definition: Audio Art 1.5-Continuum: Overlapping definitions for DJs, Turntablists, and Audio Artists 1.6-Popularity of Turntablism and Audio Art 2 BACKGROUND: Campus Radio Policy Reviews, 1999-2000 3 SURVEY 2008 3.1-Method 3.2-Results: Patterns/Trends 3.3-Examples: Pre-recorded music 3.4-Examples: Live performance 4 SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM 4.1-Difficulty with using MAPL System to determine Canadian status 4.2- Canadian Content Regulations and turntablism/audio art CONCLUSION SUMMARY Turntablism and audio art are becoming more common forms of expression on community and campus stations. Turntablism refers to the use of turntables as musical instruments, essentially to alter and manipulate the sound of recorded music. Audio art refers to the arrangement of excerpts of musical selections, fragments of recorded speech, and ‘found sounds’ in unusual and original ways. The following paper outlines past and current difficulties in regulating these newer genres of music. It reports on an examination of programs from 22 community and campus stations across Canada. Given the abstract, experimental, and diverse nature of these programs, it may be difficult to incorporate them into the CRTC’s current music categories and the current MAPL system for Canadian Content. Nonetheless, turntablism and audio art reflect the diversity of Canada’s artistic community. -

A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia by Laura

The Art of the Hustle: A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia by Laura L. Bunting-Hudson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2017 © 2017 Laura L. Bunting-Hudson All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Art of the Hustle: A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia Laura L. Bunting-Hudson How do rap artists in Bogota, Colombia come together to make music? What is the process they take to commodify their culture? Why are some rappers able to become socially mobile in this process, while others are less so? What is technology’s role in all of this? This ethnography explores those questions, as it carefully documents the strategies utilized by various rap groups in Bogota, Colombia to create social mobility, commoditize products and to create a different vision of modernity within the hip-hop community, as an alternative to the ideals set forth by mainstream Colombian society. Resistance Art Poetry (RAP), is said to have originated in the United States but has become a form of international music. In conducting ethnographic research from December of 2012 to October 2014, I was able to discover how rappers organize themselves politically, how they commoditize their products and distribute them to create various types of social mobilities. In this dissertation, I constructed models to typologize rap groups in Bogota, Colombia, which I call polities of rappers to discuss how these groups come together, take shape, make plans and execute them to reach their business goals. -

CORRECTING and REPLACING Infospace Mobile and the Island Def Jam Music Group Produce First Live Ringtone at Hip Hop Sensation Ludacris' "Red Light District" CD

CORRECTING and REPLACING InfoSpace Mobile and The Island Def Jam Music Group Produce First Live Ringtone at Hip Hop Sensation Ludacris' "Red Light District" CD CORRECTION...by InfoSpace Mobile ATLANTA--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Dec. 2, 2004--Please replace the release with the following corrected version due to multiple revisions. The corrected release reads: INFOSPACE MOBILE AND THE ISLAND DEF JAM MUSIC GROUP PRODUCE FIRST LIVE RINGTONE AT HIP HOP SENSATION LUDACRIS' "RED LIGHT DISTRICT" CD RELEASE PARTY InfoSpace Mobile and The Island Def Jam Music Group are embarking on an industry first today as the leading producer of mobile content and top hip hop label will record and publish the first live music ringtone. The recording will take place at the CD release party for the award winning, multi-platinum Def Jam South artist Ludacris and his highly anticipated 4th album Red Light District tonight in Atlanta. "I wish all my fans could come to Atlanta for this party," said Ludacris. "This will be one of the only ways for my fans to hear me live before I tour!" The deal is indicative of how music artists are embracing the mobile medium as a means to extend their brands, interact with their fans on a personal level and create new revenue streams. In addition to recording four exclusive, live ringtones, InfoSpace Mobile will be offering consumers exclusive Ludacris images through its carrier partners. The first ringtone will be a live recording of the album's first single, "Get Back," and the exclusive images will be from the "Get Back" video, directed by renowned director, Spike Jonze.