NTOZAKE SHANGE, JAMILA WOODS, and NITTY SCOTT by Rachel O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

Sal Capone – Intro for Schools

Introduction to Sal Capone: The Lamentable Tragedy Of for teachers and students From the playwright, Omari Newton: I hope this story makes you all think, laugh and feel inspired to create your own art. Sal Capone is a story about people your age chasing their dreams and fighting to survive some of the pressure associated with growing up. It's also a love letter to Hip Hop culture. I hope you enjoy our show. From the director, Diane Roberts: Theatre is a tactile medium. You feel things as much as you hear and see them. Sal Capone’s characters are ordinary people caught up in extraordinary circumstances. I hope you will be moved by how all of the elements of drama, music, video and movement come together to make you feel the triumphs and tragedies of these potent characters. What is the play about? Sal Capone: The Lamentable Tragedy Of (let’s call it Sal from here-on for short) is about many things and we hope, in watching the play, you will find meanings and themes that we haven’t yet realized are there. In particular, we hope that you will find something about you in the play. The story follows the journeys of a group of friends and Hip Hop crew who are dealing with the fatal police shooting of their friend; a talented but troubled young DJ (inspired by true events that have occurred in Montreal, Toronto, New York, San Francisco and London, UK in recent years and many others that don’t reach mass media – see links in “Resources” section). -

BROWNOUT Fear of a Brown Planet COOP AVAILABLE SHIPPING with PROMO POSTER

BROWNOUT Fear Of A Brown Planet COOP AVAILABLE SHIPPING WITH PROMO POSTER KEY SELLING POINTS • Billboard premier: Brownout Delivers Funky Cover of Public Enemy’s ‘Fight the Power’ • Fear Of A Brown Planet follows The Elmatic Instrumentals and Enter The 37th Chamber in Fat Beats Records heralded stream of instrumental takes of hip hop classics • Brownout has released past albums with Ubiquity Records (Brown Sabbath) and enjoyed a stint backing the late legend Prince • Tour dates planned for the summer of 2018 DESCRIPTION ARTIST: Brownout Twenty-eight years ago, pissed-off 12-year-olds around the universe discovered TITLE: Fear Of A Brown Planet a new planet, a Black Planet. Public Enemy’s aggressive, Benihana beats and incendiary lyrics instilled fear among parents and teachers everywhere, even CATALOG: L-FB5185 / CD-FB5185 in the border town of Laredo, Texas, home of the future founders of the Latin- Funk-Soul-Breaks super group, Brownout. The band’s sixth full-length album LABEL: Fat Beats Records Fear of a Brown Planet is a musical manifesto inspired by Public Enemy’s GENRE: Psych-Funk/Hip-Hop music and revolutionary spirit. BARCODE: 659123518512 / 659123518529 Chuck D., the Bomb Squad, Flava Flav and the rest of the P.E. posse couldn’t possibly have expected that their golden-era hip hop albums would sow the FORMAT: LP / CD seeds for countless Public Enemy sleeper cells, one that would emerge nearly HOME MARKET: Austin, Texas three decades later in Austin, Texas. Greg Gonzalez (bass) remembers a kid back in junior high hipped him to the fact that Public Enemy’s “Bring the Noise” RELEASE: 5/25/2018 is built on James Brown samples, while a teenaged Beto Martinez (guitar) $17.98 / CH / $9.98 / AH alternated between metal and hip-hop in his walk-man, and Adrian Quesada LIST PRICE: (guitar/keys) remembers falling in love with Public Enemy’s sound at an early CASE QTY: LP 30 / CD 200/1 age. -

Ernie Mcclintock's 127Th Street Repertory Ensemble

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadtjournal.org Subversive Inclusion: Ernie McClintock’s 127th Street Repertory Ensemble by Elizabeth M. Cizmar The Journal of American Drama and Theatre Volume 33, Number 2 (Spring 2021) ISNN 2376-4236 ©2021 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Ernie McClintock (1937–2003), director, acting teacher, and producer, grounded his work in the Black Power concepts of self-determination and community, but in pursuing a more inclusive theatre company, he departed from common practices of the Black Arts Movement. This departure can be attributed to his queer positionality, which has left him on the fringes of Black Arts Movement scholarship. McClintock founded four institutions: in Harlem, the Afro-American Studio for Acting & Speech (est. 1966), the 127th Street Repertory Ensemble (est. 1973), and the Jazz Theatre of Harlem (est. 1986); and in Richmond, Virginia, the Jazz Actors Theatre (est. 1991). A landmark Black theatre institution, the 127th Street Repertory Ensemble ran from 1973 to 1986, demonstrating that the spirit and work of the Black Arts Movement extended well beyond 1975, the generally accepted end date of the movement. Over more than four decades in socially and politically charged environments, McClintock established actor training rooted in Afrocentricity,[1] teaching Jazz Acting in the classroom and the rehearsal hall, which he considered an important training ground for actors. In this article, I argue that McClintock’s theatre subverted two established norms: the English repertory model and the male-dominated, heteronormative representations of the Black Arts Movement. McClintock’s legacy challenges assumptions that the Black Arts Movement was broadly misogynist and homophobic. -

Chai Release New Single/Video, “Maybe

February 24, 2021 For Immediate Release CHAI RELEASE NEW SINGLE/VIDEO, “MAYBE CHOCOLATE CHIPS” (FEAT. RIC WILSON) NEW ALBUM, WINK, OUT MAY 21ST ON SUB POP CHAI by Yoshio Nakaiso, Ric Wilson by Jackie Lee Young Japanese quartet CHAI present a new single/video, “Maybe Chocolate Chips” (Feat. Ric Wilson), from their forthcoming album, WINK, due May 21st on Sub Pop. CHAI’s past albums have been filled with playful references, in the lyrics, to food, and WINK’s intimate single “Maybe Chocolate Chips” offers an evolution of this motif. Bassist/lyricist YUUKI wanted to write a self-love song about her moles: “Things that we want to hold on to, things that we wished went away. A lot of things happen as we age and with that for me, is new moles! But I love them! My moles are like the chocolate chips on a cookie, the more you have, the happier you become! and before you know it, you're an original♡” Chicago rapper Ric Wilson, who they initially connected with at the 2019 Pitchfork Music Festival, brings smooth vocals over a laidback beat and whirring, dreamy synth. A community activist and artist based on the Southside of Chicago, he got his start with the legendary Young Chicago Authors, the Chicago-based storytelling and poetry organization which helped launch the likes of Noname, Saba, Jamila Woods, Chance The Rapper, Vic Mensa, Mick Jenkins, and many others. He’s also featured in the accompanying video, directed by Callum Scott-Dyson, which is made of fun collages and video clips in classic CHAI style. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Human Rights Expressed by Voices of the Characters in Ntozake Shange´S Plays

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature Human Rights Expressed by Voices of the Characters in Ntozake Shange´s Plays Bachelor Thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, Ph.D. Jana Veselá, DiS. Bibliografický záznam Veselá, Jana. Základní lidská práva vyjádřena hlasy postav v divadelních hrách Ntozake Shange: bakalářská práce. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, Fakulta pedagogická, Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury, 2018. 62 s. Vedoucí bakalářské práce Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, Ph.D. Bibliography Veselá, Jana. Human Rights Expressed by Voices of the Characters in Ntozake Shange´s Plays: bachelor thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, Department of English Language and Literature, 2018. 62 pages. The supervisor of the bachelor thesis Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, Ph.D. Anotace Bakalářská práce Základní lidská práva vyjádřena hlasy postav v divadelních hrách Ntozake Shange pojednává o divadelních hrách Ntozake Shange. Práce obsahuje informace o autorce, představuje typické znaky jejích her. Cílem práce je analýza myšlenkových postojů postav v hrách For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf, Spell #7, A Photograph: Lovers in Motion, Boogie Woogie Landscapes a ve hře From Okra to Greens. Součástí rozboru jsou i monology či básně, které slouží také k předvádění na jevišti. Jedná se o The Love Space Demands a I Heard Eric Dolphy in His Eyes. Práce porovnává ženské i mužské kvality postav či jejich charakterové nedostatky zasazené do černošského prostředí s ohledem na kulturní rozdíly mezi černou a bílou komunitou. Závěr práce tvoří zhodnocení oblastí lidských práv, jež jsou obsaženy v názorech postav. Abstract The bachelor thesis Human Rights Expressed by Voices of the Characters in Ntozake Shange´s Plays deals with stage plays by Ntozake Shange. -

Catalyst Vol46 No.12.Pdf

DECEMBER 11, 2015 LYST THE CATATHE INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF COLORADO COLLEGE NEWS 2 Opinion 8 SPORTS 11 LIFE 15 FRIDAY BLOCK 4 Illustration by WEEK 3 Rachel Fischman COME WITH HOCKEY STIFFS REEL TALK: VOL. 46 MIAMI IN THIRD ‘SPOTLIGHT’ ME IF YOU NO. 12 WANT TO LIVE STRAIGHT WIN REVIEW CATALYSTNEWSPAPER.COM MORE: MORE: Page 10 Photo courtesy of CC Athletics MORE: Page 11 Photo by David Andrews Page 15 #COP21 CC students get an inside look at crucial international climate negotiations at the Paris Climate Summit. CLIMATE: Page 7 Photo by Gabriella Palko In light of his new jams, ANNIE ENGEN CommunityStaff Writer healing after Planned Parenthood shooting senior Jack Sweeney mann commented on how she felt Counseling Center Director Bill Dove. sits down with the the day of the shooting. “I didn’t re- Up to six counseling sessions, free ally feel safe on campus and was re- of charge, are available for students Catalyst to discuss In the past year, there have been ally irritated by the mail that said we to take advantage of—an opportunity over 350 mass shootings in the U.S., were out of danger.,” she said. “How that many undergrads never utilize music and his problems one of them being the Planned Par- could we not be in danger when the throughout their careers at CC. You enthood shooting in Colorado Springs shooter was 15 minutes away?” are encouraged to go to the Coun- with ladies. on Nov. 27. MORE: Page 5 A certain level of distress has af- seling Center, located in Boettcher “There have been so many shoot- fected some of the students on cam- Health Center, if you are feeling un- ings, but this was close to home, so pus. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

Parody and Pastiche

Evaluating the Impact of Parody on the Exploitation of Copyright Works: An Empirical Study of Music Video Content on YouTube Parody and Pastiche. Study I. January 2013 Kris Erickson This is an independent report commissioned by the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) Intellectual Property Office is an operating name of the Patent Office © Crown copyright 2013 2013/22 Dr. Kris Erickson is Senior Lecturer in Media Regulation at the Centre ISBN: 978-1-908908-63-6 for Excellence in Media Practice, Bournemouth University Evaluating the impact of parody on the exploitation of copyright works: An empirical study of music (www.cemp.ac.uk). E-mail: [email protected] video content on YouTube Published by The Intellectual Property Office This is the first in a sequence of three reports on Parody & Pastiche, 8th January 2013 commissioned to evaluate policy options in the implementation of the Hargreaves Review of Intellectual Property & Growth (2011). This study 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 presents new empirical data about music video parodies on the online © Crown Copyright 2013 platform YouTube; Study II offers a comparative legal review of the law of parody in seven jurisdictions; Study III provides a summary of the You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the findings of Studies I & II, and analyses their relevance for copyright terms of the Open Government Licence. To view policy. this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov. uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or email: [email protected] The author is grateful for input from Dr. -

The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21St Century Stand-Up

The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21st Century Stand-Up Comedy Stage © 2018 Rachel Eliza Blackburn M.F.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 2013 B.A., Webster University Conservatory of Theatre Arts, 2005 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Theatre and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Nicole Hodges Persley Dr. Katie Batza Dr. Henry Bial Dr. Sherrie Tucker Dr. Peter Zazzali Date Defended: August 23, 2018 ii The dissertation committee for Rachel E. Blackburn certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21st Century Stand-Up Comedy Stage Chair: Dr. Nicole Hodges Persley Date Approved: Aug. 23, 2018 iii Abstract In 2014, Black feminist scholar bell hooks called for humor to be utilized as political weaponry in the current, post-1990s wave of intersectional activism at the National Women’s Studies Association conference in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Her call continues to challenge current stand-up comics to acknowledge intersectionality, particularly the perspectives of women of color, and to encourage comics to actively intervene in unsettling the notion that our U.S. culture is “post-gendered” or “post-racial.” This dissertation examines ways in which comics are heeding bell hooks’s call to action, focusing on the work of stand-up artists who forge a bridge between comedy and political activism by performing intersectional perspectives that expand their work beyond the entertainment value of the stage. Though performers of color and white female performers have always been working to subvert the normalcy of white male-dominated, comic space simply by taking the stage, this dissertation focuses on comics who continue to embody and challenge the current wave of intersectional activism by pushing the socially constructed boundaries of race, gender, sexuality, class, and able-bodiedness. -

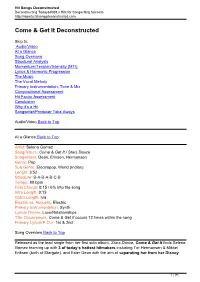

Come & Get It<Span Class="Orangetitle"> Deconstructed

Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com Come & Get It Deconstructed Skip to: Audio/Video At a Glance Song Overview Structural Analysis Momentum/Tension/Intensity (MTI) Lyrics & Harmonic Progression The Music The Vocal Melody Primary Instrumentation, Tone & Mix Compositional Assessment Hit Factor Assessment Conclusion Why it’s a Hit Songwriter/Producer Take Aways Audio/Video Back to Top At a Glance Back to Top Artist: Selena Gomez Song/Album: Come & Get It / Stars Dance Songwriters: Dean, Eriksen, Hermansen Genre: Pop Sub Genre: Electropop, World (Indian) Length: 3:52 Structure: B-A-B-A-B-C-B Tempo: 80 bpm First Chorus: 0:15 / 6% into the song Intro Length: 0:15 Outro Length: n/a Electric vs. Acoustic: Electric Primary Instrumentation: Synth Lyrical Theme: Love/Relationships Title Occurrences: Come & Get It occurs 12 times within the song Primary Lyrical P.O.V: 1st & 2nd Song Overview Back to Top Released as the lead single from her first solo album, Stars Dance, Come & Get It finds Selena Gomez teaming up with 3 of today’s hottest hitmakers including Tor Hermansen & Mikkel Eriksen (both of Stargate), and Ester Dean with the aim of separating her from her Disney 1 / 71 Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com past and to establish her as a major force within the mainstream Pop scene alongside contemporaries including Rihanna, Katy and Britney. As you’ll see within the report, Come & Get It possesses many of the “hit qualities” that are indicative of today’s chart-topping songs, but it also falls short in some key areas that preclude it from realizing its fullest potential.