Tone and Syllable in Kagoshima Japanese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delicious Local Cuisine Not to Be Missed!

0 5km Legend 268 National Highway JR Kumamoto Prefecture 117 15 ふくろ 48 Prefectural Road Michi-no-Eki Local Market Delicious local cuisine not to be missed! おこば Kirishima Shinwa Bokke Hotpot Aira AGO Nikuyaki Minamata City This hotpot is prepared using local Kurobuta Meat from the pig’s head is grilled to pork (called “Kirishima Jukusei Shinwa Buta”) perfection on a metal hot plate with and seasonal vegetables. It is available at garlic, seasoned with salt and pepper, hotels and restaurants with the “Kirishima and topped with salty spring onion 118 12● Largest Edohigan cherry tree in Japan Jukusei Shinwa Buta” flag on display. sauce before serving. Jisso ike Kirishimanma Tebaking Jisso Youth Chalet and Camp Facility 268 Chefs from famous restaurants across Kokubu (Kirishima Chicken wings stuffed with the city) gathered to create this rice bowl, which uses the specialty products of Isa city such as やたけ ●14 Isa City famed Kirishima food ingredients such as the Roppaku rice, spring onions, Gobo (Burdock Kurobuta pork, Fukuyama Kurozu Black Vinegar Buri root), etc. are battered before deep (Amberjack fish). There are two versions of this rice bowl, frying. The Tebaking is filled with the いずみ ●10Koriyama Hachiman Jinjya(Shrine) namely “Yama (mountain)” and “Umi (sea)”. charms of Isa city. To Izumi Station 267 Masaki Ebino City 48 447 Ebino P.A 221 447 Tadamoto Park ❽● 447 Ebino I.C 268 Kyoumachi-Onsen JR Kitto Line Ebino Ebino-iino Ebino-uwae 265 48 Tsurumaru Ebino J.C.T Miyazaki Prefecture 湯川内温泉かじか荘 ●18 Sogi Waterfall Yoshimatsu 21● Remains of -

KAGOSHIMA UNIVERSITY Outline 2018

National University Corporation University Emblem KAGOSHIMA UNIVERSITY Outline 2018 The university emblem was established to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the university. The emblem is designed so that the first letter K of KAGOSHIMA is made to look like a phoenix about to take flight. It is a symbol of our graduating students leaving the campus of Kagoshima University, with its rich history and tradition, and soaring high above onto the world stage. Kagoshima University 1-21-24, Korimoto Kagoshima 890-8580, Japan URL : http://www.kagoshima-u.ac.jp/ Official Mascot Character Contents “SATTSUN” Message from the President .............................................. 1 Facts and Figures .............................................................. 2 Organization .................................................................... 3 Kagoshima University Fundamental Values ........................ 4 Strategic Study Fields ........................................................ 5 Courses Offered by Kagoshima University ......................... 6 Undergraduate Faculties ................................................... 8 Graduate Schools ............................................................10 Institutes for Education and Research ...............................12 Joint - Use Facilities .........................................................14 Number of International Students .....................................15 The mascot character was selected by the students through voting. The design was Overseas Partner -

Where Modernization in Japan Began

Where Modernization in Japan Began Shuseikan Reverberatory Furnace Former Foreign Engineer’s Residence( Ijinkan) Former Machinery Factory(now Shokoshuseikan museum) Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution Old Photo of Kagoshima Spinning Mill and the Engineer's Rasidence(1872) Listed as UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site in July 2015! Shokoshuseikan museum Shokoshuseikan museum Takeo Nabeshima Family Archives, Takeo City Collection Shuseikan as depicted in the ‘Pictorial map Nariakira Shimadzu, 11th lord of of Sasshu-Kagoshima’. the Satsuma Clan This painting depicting the Iso area is drawn by a Lord Shimadzu’s initiation of the 1 retainer of the Saga Clan in 1857. It is said that Shuseikan Project had a great as Japan’s first Western-style industrial complex, influence on the modernization of 3 2 Shuseikan employed about 1200 workers at its Japan. peak. 1 The stone foundation of the reverberatory furnace. There were originally two tower furnaces built atop the foundation. 2 The reveratory furnace that manufactured cannons from melted iron was built according to a translated foreign text. 3 There is an opening for ventilation at the center of the remaining stone foundation. Shoko Shuseikan Collection In 1852, full-scale construction of The origins of‘Shuseikan’ the reverberatory furnace began. In the 19th century, as countries such as Britain, France, and the U.S.A. made steady forays into Asia, the Satsuma Clan at the with its brilliant and southernmost tip of Japan was the first to face threats from foreign countries. The move to take caution against foreign advances intensified in the Satsuma Clan after China was defeated in the First Opium War in 1842. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Seasonal Variations of Volcanic Ash and Aerosol Emissions Around Sakurajima Detected by Two Lidars

atmosphere Article Seasonal Variations of Volcanic Ash and Aerosol Emissions around Sakurajima Detected by Two Lidars Atsushi Shimizu 1,* , Masato Iguchi 2 and Haruhisa Nakamichi 2 1 National Institute for Environmental Studies, Tsukuba 305-8506, Japan 2 Sakurajima Volcano Research Center, Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University, Kagoshima 891-1419, Japan; [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (H.N.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-29-850-2489 Abstract: Two polarization-sensitive lidars were operated continuously to monitor the three-dimensional distribution of small volcanic ash particles around Sakurajima volcano, Kagoshima, Japan. Here, we estimated monthly averaged extinction coefficients of particles between the lidar equipment and the vent and compared our results with monthly records of volcanic activity reported by the Japan Meteorological Agency, namely the numbers of eruptions and explosions, the density of ash fall, and the number of days on which ash fall was observed at the Kagoshima observatory. Elevated extinction coefficients were observed when the surface wind direction was toward the lidar. Peaks in extinction coefficient did not always coincide with peaks in ash fall density, and these differences likely indicate differences in particle size. Keywords: volcanic ash; aerosol; lidar; extinction coefficient; horizontal wind Citation: Shimizu, A.; Iguchi, M.; 1. Introduction Nakamichi, H. Seasonal Variations of Volcanic eruptions are a natural source of atmospheric aerosols [1]. In the troposphere Volcanic Ash and Aerosol Emissions and stratosphere, gaseous SO2 is converted to sulfate or sulfuric acid within several around Sakurajima Detected by Two days, which can remain in the atmosphere for more than a week. -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

Spring Summer Autumn Winter

Rent-A-Car und Kagoshi area aro ma airpo Recommended Seasonal Events The rt 092-282-1200 099-261-6706 Kokura Kokura-Higashi I.C. Private Taxi Hakata A wide array of tour courses to choose from. Spring Summer Dazaifu I.C. Jumbo taxi caters to a group of up to maximum 9 passengers available. Shin-Tosu Usa I.C. Tosu Jct. Hatsu-uma Festival Saga-Yamato Hiji Jct. Enquiries Kagoshima Taxi Association 099-222-3255 Spider Fight I.C. Oita The Sunday after the 18th day of the Third Sunday of Jun first month of the lunar calendar Kurume I.C. Kagoshima Jingu (Kirishima City) Kajiki Welfare Centre (Aira City) Spider Fight Sasebo Saga Port I.C. Sightseeing Bus Ryoma Honeymoon Walk Kirishima International Music Festival Mid-Mar Saiki I.C. Hatsu-uma Festival Late Jul Early Aug Makizono / Hayato / Miyama Conseru (Kirishima City) Tokyo Kagoshima Kirishima (Kirishima City) Osaka (Itami) Kagoshima Kumamoto Kumamoto I.C. Kirishima Sightseeing Bus Tenson Korin Kirishima Nagasaki Seoul Kagoshima Festival Nagasaki I.C. The “Kirishima Sightseeing Bus” tours Late Mar Early Apr Late Aug Shanghai Kagoshima Nobeoka I.C. Routes Nobeoka Jct. M O the significant sights of Kirishima City Tadamoto Park (Isa City) (Kirishima City) Taipei Kagoshima Shinyatsushiro from key trans portation hubs. Yatsushiro Jct. Fuji Matsuri Hong Kong Kagoshima Kokubu Station (Start 9:00) Kagoshima Airport The bus is decorated with a compelling Fruit Picking Kirishima International Tanoura I.C. (Start 10:20) design that depicts the natural surroundings (Japanese Wisteria Festival) Music Festival Mid-Apr Early May Fuji (Japanese Wisteria) Grape / Pear harvesting (Kirishima City); Ashikita I.C. -

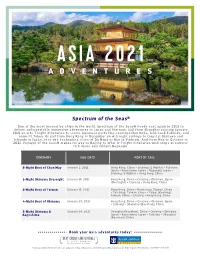

Spectrum of the Seas®

Spectrum of the Seas® One of the most innovative ships in the world, Spectrum of the Seas® heads east again in 2021 to deliver unforgettable immersive adventures to Japan and Vietnam. Sail from Shanghai starting January 2021 on 4 to 7 night itineraries to iconic Japanese ports like cosmopolitan Kobe, laid-back Fukuoka, and neon-lit Tokyo. Or sail from Hong Kong in December on 4-5 night sailings to tropical Okinawa and Ishigaki in Japan, or to the enchanting cities of Da Nang or Hue in Vietnam. And from May to October in 2021, Voyager of the Seas® makes its way to Beijing to offer 4-7 night itineraries with stops at culture- rich Kyoto and vibrant Nagasaki. ITINERARY SAIL DATE PORT OF CALL 8-Night Best of Chan May January 2, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Cruising (2 Nights) • Fukuoka, Japan • Kagoshima, Japan • Nagasaki, Japan • Cruising (2 Nights) • Hong Kong, China 5-Night Okinawa Overnight January 10, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Cruising • Okinawa, Japan (Overnight) • Cruising • Hong Kong, China 5-Night Best of Taiwan January 15, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Kaohsiung, Taiwan, China • Taichung, Taiwan, China • Taipei (Keelung), Taiwan, China • Cruising • Hong Kong, China 4-Night Best of Okinawa January 20, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Cruising • Okinawa, Japan • Cruising • Shanghai (Baoshan), China 5-Night Okinawa & January 24, 2021 Shanghai (Baoshan), China • Cruising • Okinawa, Kagoshima Japan • Kagoshima, Japan • Cruising • Shanghai (Baoshan), China Book your Asia adventures today! Features vary by ship. All itineraries are subject to change without -

Acta Linguistica Asiatica

Acta Linguistica Asiatica Volume 1, Number 3, December 2011 ACTA LINGUISTICA ASIATICA Volume 1, Number 3, December 2011 Editors : Andrej Bekeš, Mateja Petrov čič Editorial Board : Bi Yanli (China), Cao Hongquan (China), Luka Culiberg (Slovenia), Tamara Ditrich (Slovenia), Kristina Hmeljak Sangawa (Slovenia), Ichimiya Yufuko (Japan), Terry Andrew Joyce (Japan), Jens Karlsson (Sweden), Lee Yong (Korea), Arun Prakash Mishra (India), Nagisa Moritoki Škof (Slovenia), Nishina Kikuko (Japan), Sawada Hiroko (Japan), Chikako Shigemori Bu čar (Slovenia), Irena Srdanovi ć (Japan). © University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Arts, 2011 All rights reserved. Published by : Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani (Ljubljana University Press, Faculty of Arts) Issued by: Department of Asian and African Studies For the publisher: Andrej Černe, the dean of the Faculty of Arts Journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0). Journal’s web page : http://revije.ff.uni-lj.si/ala/ Journal is published in the scope of Open Journal Systems ISSN: 2232-3317 Abstracting and Indexing Services : COBISS, Directory of Open Access Journals, Open J-Gate and Google Scholar. Publication is free of charge. Address: University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Arts Department of Asian and African Studies Ašker čeva 2, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .....................................................................................................................5-6 RESEARCH -

Download Download

The Complexity of Modernization: How theGenbunitchi and Kokugo Movements Changed Japanese by Mark Laaninen In 1914, the novelist Natsume Soseki published Of the many linguistic crusades of the Meiji his novel Kokoro. Incorporating themes of isolation Period, the genbunitchi and kokugo movements had and detachment into the tragedy of the main the largest and most vocal following. Genbunitchi character Sensei, Kokoro solidified Soseki as one focuses on unifying written and spoken Japanese of Japan’s earliest and greatest modern Japanese into one easily learnable language.2 Advocates writers.1 Yet more than their themes made Soseki’s of genbunitchi argued that the old Tokugawa novels modern. By 1914, writers like Soseki used a wakankonkobun, kanbun, and sorobun were far simple, colloquial style of writing which radically too complicated for anyone without huge amounts differed from the more complex character-based of time to learn. Instead, they wanted a simplified, system used by writers even thirty years prior. What colloquial style that allowed for greater literacy and ease of communication.3 The desired form of writing fueled this change? Many point to the language varied among genbunitchi advocates, however. Some, reform movements of the Meiji Era, especially the like Fukuzawa Yukichi, simply reduced the number genbunitchi and kokugo movements. These language of kanji, or Chinese-style characters, in their writing, reforms attempted to pioneer a new Japanese, one while others like Nishi Amane wanted a wholesale united and tailored for a modern world. Although adoption of romaji, or a Latin alphabet.4 Yet for many they had a far-reaching effect in their own period, reformers, changing written Japanese could only be the long-term impact of these movements is more useful after spoken Japanese had been united. -

Rail Pass Guide Book(English)

JR KYUSHU RAIL PASS Sanyo-San’in-Northern Kyushu Pass JR KYUSHU TRAINS Details of trains Saga 佐賀県 Fukuoka 福岡県 u Rail Pass Holder B u Rail Pass Holder B Types and Prices Type and Price 7-day Pass: (Purchasing within Japan : ¥25,000) yush enef yush enef ¥23,000 Town of History and Hot Springs! JR K its Hokkaido Town of Gourmet cuisine and JR K its *Children between 6-11 will be charged half price. Where is "KYUSHU"? All Kyushu Area Northern Kyushu Area Southern Kyushu Area FUTABA shopping! JR Hakata City Validity Price Validity Price Validity Price International tourists who, in accordance with Japanese law, are deemed to be visiting on a Temporary Visitor 36+3 (Sanjyu-Roku plus San) Purchasing Prerequisite visa may purchase the pass. 3-day Pass ¥ 16,000 3-day Pass ¥ 9,500 3-day Pass ¥ 8,000 5-day Pass Accessible Areas The latest sightseeing train that started up in 2020! ¥ 18,500 JAPAN 5-day Pass *Children between 6-11 will be charged half price. This train takes you to 7 prefectures in Kyushu along ute Map Shimonoseki 7-day Pass ¥ 11,000 *Children under the age of 5 are free. However, when using a reserved seat, Ro ¥ 20,000 children under five will require a Children's JR Kyushu Rail Pass or ticket. 5 different routes for each day of the week. hu Wakamatsu us Mojiko y Kyoto Tokyo Hiroshima * All seats are Green Car seats (advance reservation required) K With many benefits at each International tourists who, in accordance with Japanese law, are deemed to be visiting on a Temporary Visitor R Kyushu Purchasing Prerequisite * You can board with the JR Kyushu Rail Pass Gift of tabi socks for customers J ⑩ Kokura Osaka shops of JR Hakata city visa may purchase the pass. -

An Analysis of Human Damage Caused by Recent Heavy Rainfall Disasters in Japan

An analysis of human damage caused by recent heavy rainfall disasters in Japan Motoyuki USHIYAMA¹ ¹ Iwate Prefectural University, Iwate, Japan Abstract: The development and analysis of a database that will aid in the mitigation of human damage (that is, deaths or missing persons) caused by natural disasters are very important, and a method to do these tasks has been established in Japan. First, we developed a victim database for the typhoon No. 0423 disaster, the typhoon No. 0514 disaster and the heavy rainfall disaster of July 2006, and the victims were classified based on whether they were dead or missing. In the present study, we estimate whether any loss was mitigated by the use of disaster information. In the case of the typhoon No.0514 disaster, the estimated mitigation percentage of victims is 75%. However, in the case of the typhoon No.0423 disaster, the mitigation is only 36%. Disaster information is a useful disaster mitigation measure, but there is a limit to its effect. Key words: heavy rainfall disaster, deaths or missing persons, disaster information, disaster mitigation. 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODOLOGY Analyzing the causes of death in a natural disaster is Basic data come from the outline of disaster statistics important for disaster prevention efforts. In Japan, there provided by the Fire and Disaster Management Agency have been studies on the causes of death during earthquakes (FDMA). Detailed information of victims was collected (Japan's National Land Agency, 2000, Kobayashi, 1981), from the national newspapers, local newspapers and web and there have been several studies on the human damage pages of the prefectural offices, municipality offices and caused by heavy rainfall disasters, such as the case studies of elsewhere.