The “I” of the Text: a Psychoanalytic Theory Perspective on Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture

Running head: KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 1 Kawaii Boys and Ikemen Girls: Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture Grace Pilgrim University of Florida KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………4 The Construction of Gender…………………………………………………………………...6 Explication of the Concept of Gender…………………………………………………6 Gender in Japan………………………………………………………………………..8 Feminist Movements………………………………………………………………….12 Creating Pop Culture Icons…………………………………………………………………...22 AKB48………………………………………………………………………………..24 K-pop………………………………………………………………………………….30 Johnny & Associates………………………………………………………………….39 Takarazuka Revue…………………………………………………………………….42 Kabuki………………………………………………………………………………...47 Creating the Ideal in Johnny’s and Takarazuka……………………………………………….52 How the Companies and Idols Market Themselves…………………………………...53 How Fans Both Consume and Contribute to This Model……………………………..65 The Ideal and What He Means for Gender Expression………………………………………..70 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..77 References……………………………………………………………………………………..79 KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 3 Abstract This study explores the construction of a uniquely gendered Ideal by idols from Johnny & Associates and actors from the Takarazuka Revue, as well as how fans both consume and contribute to this model. Previous studies have often focused on the gender play by and fan activities of either Johnny & Associates talents or Takarazuka Revue actors, but never has any research -

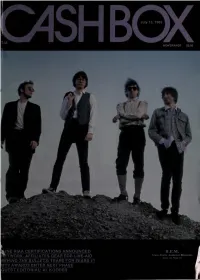

Cashbox Subscription: Please Check Classification;

July 13, 1985 NEWSPAPER $3.00 v.'r '-I -.-^1 ;3i:v l‘••: • •'i *. •- i-s .{' *. » NE RIAA CERTIFICATIONS ANNOUNCED R.E.M. AFFILIATES LIVE-AID Crass Roots Audience Blossoms TWORK, GEAR FOR Story on Page 13 WEHIND THE BULLETS: TEARS FOR FEARS #1 MTV AWARDS ENTER NEXT PHASE GUEST EDITORIAL: AL KOOPER SUBSCRIPTION ORDER: PLEASE ENTER MY CASHBOX SUBSCRIPTION: PLEASE CHECK CLASSIFICATION; RETAILER ARTIST I NAME VIDEO JUKEBOXES DEALER AMUSEMENT GAMES COMPANY TITLE ONE-STOP VENDING MACHINES DISTRIBUTOR RADIO SYNDICATOR ADDRESS BUSINESS HOME APT. NO. RACK JOBBER RADIO CONSULTANT PUBLISHER INDEPENDENT PROMOTION CITY STATE/PROVINCE/COUNTRY ZIP RECORD COMPANY INDEPENDENT MARKETING RADIO OTHER: NATURE OF BUSINESS PAYMENT ENCLOSED SIGNATURE DATE USA OUTSIDE USA FOR 1 YEAR I YEAR (52 ISSUES) $125.00 AIRMAIL $195.00 6 MONTHS (26 ISSUES) S75.00 1 YEAR FIRST CLASS/AIRMAIL SI 80.00 01SHBCK (Including Canada & Mexico) 330 WEST 58TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ' 01SH BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 5 — July 13, 1985 C4SHBO( Guest Editorial : T Taking Care Of Our Own ^ GEORGE ALBERT i. President and Publisher By A I Kooper MARK ALBERT 1 The recent and upcoming gargantuan Ethiopian benefits once In a very true sense. Bob Geldof has helped reawaken our social Vice President and General Manager “ again raise an issue that has troubled me for as long as I’ve been conscience; now we must use it to address problems much closer i SPENCE BERLAND a part of this industry. We, in the American music business do to home. -

Meyer Tech Pak012617.Indd

• Technical Information • Policies & Procedures • Fee Schedule for Rental & Services LOAD-IN AREA The loading dock is located on stage level, directly off upstage right. The dock has one 8’-0” wide x 10’-0” high (2.44m x 3.05m) overhead door. Dock height is 24” (.61m). There is NO leveler, and there is NO truck ramp. The loading area is 16’ wide x 22’ long with 12’ ceilings, in a wedge shape. Access to stage is through a 10’ wide x 11’ high overhead door upstage right. Access to the dressing rooms is by stairs or by elevator. CARPENTRY Seating Capacity Maximum Capacity: 1011 Orchestra 537 Grand Tier: 90 Mezzanine: 384 Handicapped Accessible: 8 Additional on Grand Tier Level Stage Dimensions Proscenium w: 49’-6” (15.09m) h:23’-0” (7.01m) Depth (plaster to back wall) 28’-0” (8.53m) Apron Curved 5’-0” (1.52m) at centerline Wing Space • Stage right 10’-0” (~3.05m) • Stage left 13’-0” (~3.96m) Orchestra Pit none Stage to Audience 4’-0” (1.21m) NFORMATION Stage Floor Material: 1/4” hardboard (Duron) I Color: Black Condition: Good Sub floor: 1 layer of 3/4” plywood 2x4 sleepers (24” O.C.) on resilient pads House Drapery: House Curtain- Scarlet; Manual Fly Item Number Material WxH Legs 8 black velour 10’ x 25’ (3.05m x 7.62m) Borders 4 black velour 60’ x 10’ (18.23m x 3.05m) Full Black 2 black velour 60’ x 25’ (18.23m x 7.62m) Line Set Data: Grid height: 53’-9” (16.38m) High trim: 50’-11” (15.52m) Low trim: 5’-8” (1.72m) Total Line Sets: 26 single purchase Arbor Capacity: 1500 lbs (680kg) ECHNICAL Weight Available: 8702 lbs (3947kg) Weight Size: 19 lbs (8.6 kg) Pipe Length: 60’-0” (18.29m) T Pipe size: 26 @ 1-1/2” Schedule 40 Lock Rail: Stage Left, stage level Line Plot: Enclosed Shop Area: There is NO on-site scenery shop, and there is no off-stage area for working on scenery. -

The Korean Wave As a Localizing Process: Nation As a Global Actor in Cultural Production

THE KOREAN WAVE AS A LOCALIZING PROCESS: NATION AS A GLOBAL ACTOR IN CULTURAL PRODUCTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Ju Oak Kim May 2016 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Department of Journalism Nancy Morris, Professor, Department of Media Studies and Production Patrick Murphy, Associate Professor, Department of Media Studies and Production Dal Yong Jin, Associate Professor, School of Communication, Simon Fraser University © Copyright 2016 by Ju Oak Kim All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation research examines the Korean Wave phenomenon as a social practice of globalization, in which state actors have promoted the transnational expansion of Korean popular culture through creating trans-local hybridization in popular content and intra-regional connections in the production system. This research focused on how three agencies – the government, public broadcasting, and the culture industry – have negotiated their relationships in the process of globalization, and how the power dynamics of these three production sectors have been influenced by Korean society’s politics, economy, geography, and culture. The importance of the national media system was identified in the (re)production of the Korean Wave phenomenon by examining how public broadcasting-centered media ecology has control over the development of the popular music culture within Korean society. The Korean Broadcasting System (KBS)’s weekly show, Music Bank, was the subject of analysis regarding changes in the culture of media production in the phase of globalization. In-depth interviews with media professionals and consumers who became involved in the show production were conducted in order to grasp the patterns that Korean television has generated in the global expansion of local cultural practices. -

Dramatis Pupae: the Special Agency of Puppet Performances

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Theatre & Dance ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-8-2009 Dramatis Pupae: The pS ecial Agency of Puppet Performances Casey Mráz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/thea_etds Recommended Citation Mráz, Casey. "Dramatis Pupae: The peS cial Agency of Puppet Performances." (2009). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/thea_etds/ 35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theatre & Dance ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DRAMATIS PUPAE: THE SPECIAL AGENCY OF PUPPET PERFORMANCES BY CASEY MRÁZ B.U.S., University Studies, University of New Mexico, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Dramatic Writing The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico April 2009 DRAMATIS PUPAE: THE SPECIAL AGENCY OF PUPPET PERFORMANCES BY CASEY MRÁZ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Dramatic Writing The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico April 2009 Dramatis Pupae: The Special Agency of Puppet Performances By Casey Mráz B.U.S., University Studies, University of New Mexico, 2004 M.F.A., Dramatic Writing, University of New Mexico, 2009 ABSTRACT Puppets have been used in performance by many cultures for thousands of years. Their roles in performance are constantly changing and evolving. Throughout the twentieth century there has been much contention between performance theorists over what defines a puppet. -

Disney's the Little Mermaid

Disney’s The Little Mermaid A production by Variety Children’s Theatre October 24 - 26, 2014 Touhill Performing Arts Center University of Missouri - St. Louis Dear Educators, Variety Children’s Theatre is proud to present its sixth annual production, Disney’s The Little Mermaid. Once again under the direction of Tony Award nominee Lara Teeter, this show boasts some of the city’s greatest professional actors and designers. We all eagerly await the results of their craft— bringing the story of Ariel to life. Be sure that you and your students are there to experience the beauty of an opera house with a full orchestra, dazzling sets and brilliant costumes (including a trip under the sea). Musical theatre can enhance learning on so many levels. It builds an appreciation for the arts, brings to life a lesson on the parts of a story (i.e. characters, plot, conflict) and provides the perfect setting to learn a thing or two about fairy tales and why they are important windows into important facets of our lives. Variety takes that learning one step further, however, presenting an inclusive cast where adult equity actors, talented adults from community theatre, and gifted theatrical children, work side-by-side with children who have a wide range of disabilities. The production is truly a lesson in acceptance, perseverance and the “I CAN” spirit that shines through all Variety programs. In the near future, we will have Disney’s The Little Mermaid study guide to help you incorporate the show into your curriculum and to help your students prepare for the show. -

Agriculture Architecture & Construction

FOR LANCASTER COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT PAGE 2 COURSEGUIDE SCHEDULE CHANGES A CHALLENGE AGRICULTURE Prepare to succeed Agricultural mill or lumber company. You’ll build skills in the operation of When changes should be made You’ve heard the question a thou- Mechanics & Technology mechanized harvesting equip- sand times – “What do you want to ment and its maintenance. At the end of this school year, review your choices. Prerequisite: Agricultural Science & You need to change your schedule then only if do after you graduate?” Technology Grades: 10-11 Horticulture u a counselor finds that your selections aren’t ap- If you’re like I was in high school, Credit: 1 unit Introduction propriate Offered: Andrew Jackson, Buford, Prerequisite: Agricultural Science & you really don’t know. Indian Land Technology (at Andrew Jackson and u you have failed a course And the good news is, right now, Buford) You’ll learn about agricul- u tural occupations as you learn Grades: 10-12 you’ve chosen a course that won’t be offered you don’t have to know. Credit: 1 unit more about FFA and how it u you don’t meet prerequisites. But that doesn’t mean you Offered: Andrew Jackson, Buford, supports industries. Indian Land shouldn’t be thinking about it – ex- You’ll get an overview of You’ll study house plants, What a counselor says topics covered in detail in fruit crops, landscaping and ploring careers, discovering your “You need to realize that wanting to be in classes Horticulture and Forestry so greenhouses. strengths and your interests, learn- with friends or with specific teachers or to have you can decide if you want to You’ll learn plant identifica- ing all you can so you’ll have lots of certain periods free are not valid reasons to ask to take any of these courses. -

LHAT 40Th Anniversary National Conference July 17-20, 2016

Summer 2016 Vol. 39 No. 2 IN THE LEAGUE OF HISTORIC AMERICAN THEATRES LEAGUE LHAT 40th Anniversary National Conference 9 Newport Drive, Ste. 200 Forest Hill, MD 21050 July40th 17-20, ANNUAL 2016 (T) 443.640.1058 (F) 443.640.1031 WWW.LHAT.ORG CONFERENCE & THEATRE TOUR ©2016 LEAGUE OF HISTORIC AMERICAN THEATRES. Chicago, IL ~ JULY17-20, 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Greetings from Board Chair, Jeffery Gabel 2016 Board of Directors On behalf of your board of directors, welcome to Chicago and the L Dana Amendola eague of Historic American Theatres’ 40th Annual Conference Disney Theatrical Group and Theatre Tour. Our beautiful conference hotel is located in John Bell the heart of Chicago’s historic theatre district which has seen FROM it all from the rowdy heydays of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show to Tampa Theatre Randy Cohen burlesque and speakeasies to the world-renowned Lyric Opera, Americans for the Arts Steppenwolf Theatre and Second City. John Darby The Shubert Organization, Inc. I want to extend an especially warm welcome to those of you Michael DiBlasi, ASTC who are attending your first LHAT conference. You will observe old PaPantntaggeses Theh attrer , LOL S ANANGGELEL S Schuler Shook Theatre Planners friends embracing as if this were some sort of family reunion. That’s COAST Molly Fortune because, for many, LHAT is a family whose members can’t wait Newberry Opera House to catch up since last time. It is a family that is always welcoming Jeffrey W. Gabel new faces with fresh ideas and even more colorful backstage Majestic Theater stories. -

Carshitsthe Hits Theroad

Contents | Zoom In | Zoom Out For navigation instructions please click here Search Issue | Next Page THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION July 2006 ™ Disney/Pixar's Cars Hits the Road TerrificTerrifi c MTV2 Talent Welcomes Flocks to NewToonNew Toon Annecy Rebellion ww_____________________________________________________w.animationmagazine.ne t Contents | Zoom In | Zoom Out For navigation instructions please click here Search Issue | Next Page A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B !FTERYEARSWEDECIDEDWE³D 8PVMESFDPNNFOE #FMJFWFZPVTIPVME 5IJOL#BSEFMJT #BSEFMUPBGSJFOE CF¿G¿M¿¿F¿YJCMFBOESPMM "SUJTUESJWFOBOEUIBU XJUIUIFQVODIFT UIFZIBWFBDSFBUJWFWPJDF XPVMEMJLFUPTFFNPSFBEWFSUJTJOHQSPNPUJPOGPSUIFTUVEJPEPOF XXXCBSEFMDBKPCT______________________ _________________________!CBSEFMDB A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B ASKWHATOUREMPLOYEESTHOUGHT 'FFM$IBMMFOHFE &OKPZCFJOHIFSF 'FFMZPVOFFEUP BOEUIBU#BSEFMJT UIJOLJUµTBGVO CFQSFQBSFEUP BHPPEDBSFFSNPWF QMBDFUPXPSL XPSLZPVS#VUUPGG /H ANDBYTHEWAY 7ERE(IRING 6ISITUSAT!NNECYSTAND A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B ____________________________ ___________________ A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B A A Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page EF MaGS MAGAZINE B Volume 20, Issue 7, Number 162, July 2006 CONTENTS 6 Frame-by-Frame The Monthly Animation Planner ... Tom Goes to the Mayor Again... Babar Stumps for Ecology ...Strapontin Makes Plans for Sinbad of the Stars. -

Performance, Power & Production

PERFORMANCE, POWER & PRODUCTION A SELECTIVE, CRITICAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE RADIO INTERVIEW Kathryn McDonald Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. II ABSTRACT Title: Performance, Power & Production. A selective, critical and cultural history of the radio interview Author: Kathryn McDonald This thesis charts the historical evolution of the ‘personal’ radio interview, in order to understand its use as a speech device, a social relationship and a communicative genre. Four contrasting styles of interviewing have been chosen to illustrate key moments and to illuminate significant shifts in the history of UK broadcasting: Desert Island Discs (1942-1954), The Radio Ballads (1958-64 & 2006), the confessional style phone interview format on independent local radio (1975) and Prison Radio projects (1993-present). These cases draw together an assortment of live and pre-recorded material, across a variety of genres that encompass over seventy years of production output, granting an opportunity to demonstrate the specificities of each example, whilst also identifying any overarching themes or differences. Primary research has been carried out using an assortment of audio content and written archive, comprising of scripts, memos, letters, diaries, training documents, contracts, policies and guidelines, which give us a further sense of how this method of talk has developed over the decades. -

1 2 June 2016 an Unrivalled Season This Summer and Autumn at The

2 June 2016 An unrivalled season this summer and autumn at the National Theatre Amadeus by Peter Shaffer with Lucian Msamati as Salieri The Red Barn, a new play by David Hare Stuff Happens, a rehearsed reading of David Hare's landmark play, staged to coincide with the publication of the Chilcot report Peter Pan, a Bristol Old Vic co-production directed by Sally Cookson with Sophie Thompson as Captain Hook/Mrs Darling and Paul Hilton as Peter Our Ladies of Perpetual Succour, a National Theatre of Scotland and Live Theatre co-production A Pacifist’s Guide to the War on Cancer, a Complicite Associates co-production with the National Theatre, in association with HOME Manchester River Stage, the National Theatre’s outdoor arts and music festival, returns to present a host of free weekend entertainment from 29 July to 29 August. The festival hosts takeover weekends from Latitude Festival, Rambert Dance Company, Bristol’s Mayfest, East London’s The Glory and the NT. Each weekend will stage the very best in live music, dance, performance, DJs and family workshops Connections 21, celebrating 21 years of the world’s largest youth arts festival. This autumn, Peter Shaffer’s classic play Amadeus makes a long-awaited return to the National after 37 years. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is a rowdy young prodigy who arrives in Vienna determined to make a splash. Awestruck by his genius, Court Composer Antonio Salieri has the power to promote his talent or destroy it. Seized by obsessive jealousy he begins a war with Mozart, with music and, ultimately, with God. -

Grammy® and Oscar® Award-Winning Artist Christopher Cross Sails Into Montalvo at the Lilian Fontaine Garden Theatre August 19

For Immediate Release Contact: Diane Maxwell July 14, 2011 408‐961‐5841 [email protected] Grammy and Oscar Award‐Winning Artist Christopher Cross Sails into Montalvo at the Lilian Fontaine Garden Theatre August 19 Up and Coming Vocalist Jenn Grinels to Open for Christopher Cross Saratoga, CA Contemporary music superstar Christopher Cross sails into Montalvo’s outdoor Lilian Fontaine Garden Theatre Friday, August 19, where he’ll fete fans with his mega‐hit ballads. By far the biggest adult contemporary artist of the 80s, Cross will dazzle audiences with his smooth, sophisticated sounds and timelessly popular hits, as well as songs from his newly released CD, doctor faith. Jenn Grinels, an up‐and‐coming singing sensation from Cupertino, California, will open for the popular crooner. Cross virtually defined adult contemporary radio when his self‐titled debut album with the lead single, “Ride Like the Wind,” rocketed to #2 on the charts, followed by the second single, “Sailing.” With two additional top 20 hits, “Never Be the Same,” and “Say You’ll Be Mine,” he walked off with an unprecedented record‐setting five Grammys in 1981, including Best New Artist and Song of the Year for "Sailing." Cross soon scored a second #1 hit, as well as an Academy Award, with "Arthur's Theme (Best That You Can Do)," which he co‐wrote with Burt Bacharach, Carole Bayer Sager, and Peter Allen for the Dudley Moore smash hit film Arthur. Cross’ much‐anticipated second album Another Page came out in 1983 and produced the hits "All Right," "No Time for Talk," and a top 10 entry for "Think of Laura," a song featured prominently in the daytime drama, General Hospital.