Absolute Kippleization and the Plastosystem: Metaphors to Address Complex Science in the Age of the Anthropocene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 2016 Place in the Land of Israel

14 1 Bible Study and Bon-Fire Nights! Orchard Hill Church Join us this summer for Bible study, volleyball, and bonfires! We will begin with a video based Bible study each week that highlights a different story, event, and June 2016 place in the land of Israel. You can see the sites of some of the greatest events in our Bible as well as begin to understand the historical context behind God’s Word. This is a thrilling month at OHC as we bring a number of After our Bible study we will spend the second part of the night playing volleyball individuals into a new season of leadership at OHC. Can you and eating some s’mores over the fire! think of any greater privilege than to be called to be a leader in the church of Jesus Christ? The church is his Body, his Bride, the Temple of his Spirit, his Flock, his Army, and his Family. High School– Monday Nights, starting June 13, 7:00 - 9:00 PM Can you think of any greater responsibility than leading his church? Middle School– Wednesday Nights, starting June 15, 7:00 - 9:00 PM This is why God's Word has laid before us such challenging requirements for Christian leadership. The standards are rightly high, not only for the sake of the church's vitality but also for the sake of the leader's vitality. As we look into Gods word (1 Timothy 3:1-13, 2 Timothy 2:1-13, Titus 1:5-9, Acts 6:1-6, and Exodus 18:21-22.) the qualifications spelled out for leadership in these Anyone want to passages can be summarized in four words: commitment, conviction, competency, and character. -

May 4, 2020 Council Packet

TENTATIVE AGENDA REGULAR CITY COUNCIL MEETING CLINTON BUILDING 501 CAMPANELLA DRIVE Monday, May 4, 2020 5:00 P.M. I. CALL TO ORDER II. RECORD OF ATTENDANCE III. OPENING PRAYER IV. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE V. APPROVAL OF CITY COUNCIL MINUTES A. Regular Council Minutes February 24, 2020 B. Regular Council Minutes March 9, 2020 C. Regular Council Minutes – Executive Session March 24, 2020 D. Regular Council Minutes April 3, 2020 E. Regular Council Minutes April 29, 2020 VI. PUBLIC HEARING – FY21 BUDGET VII. ITEMS OF BUSINESS A. Consideration of Library Board of Trustee Appointments B. Approve Location for Welcome to Sikeston Monument Sign C. Renewal of DAEOC Homeless Shelter Agreement D. 2nd Reading & Consideration, Bill #6187, Authorization for Alcohol Considered as a Conditional Use in C-1 Zoning E. 2nd Reading & Consideration, Bill #6186, Mowing Right-of-Ways F. 1st Reading, Bill #6188, Re-Adoption of Fair Housing Policy G. Approval of Street Program Projects – Lambert Engineering H. 1st & 2nd Reading, Emergency Bill #6193, Establishing Chapter 650-Firework Sales I. 1st & 2nd Reading, Emergency Bill #6195, Zoning for Firework Stands J. Other Items as May Be Determined During the Course of the Meeting VIII. ADJOURNMENT INTO EXECUTIVE SESSION Property (RSMo 610.021(2)) Personnel (RSMo 610.021(3)) IX. ADJOURNMENT Dated this 29th day of April 2020 Rhonda Council Rhonda Council, Deputy City Clerk The City of Sikeston complies with ADA guidelines. Notify Rhonda Council at 471-2512 (TDD Available) to notify the City of any reasonable accommodation needed to participate in the City Council’s Meeting. REGULAR CITY COUNCIL MEETING FEBRUARY 24, 2020 The regular Sikeston City Council meeting of February 24, 2020 was called to order at 7:30 a.m. -

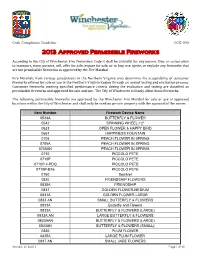

From the City Manager

Code Compliance Guideline CCG-003 2013 APPROVED PERMISSIBLE FIREWORKS According to the City of Winchester Fire Prevention Code it shall be unlawful for any person, firm, or corporation to transport, store, possess, sell, offer for sale, expose for sale, or to buy, use, ignite, or explode any fireworks that are not permissible fireworks as approved by the Fire Marshal. Fire Marshals from various jurisdictions in the Northern Virginia area determine the acceptability of consumer fireworks offered for sale or use in the Northern Virginia Region through an annual testing and evaluation process. Consumer fireworks meeting specified performance criteria during the evaluation and testing are classified as permissible fireworks and approved for sale and use. The City of Winchester will only allow those fireworks. The following permissible fireworks are approved by the Winchester Fire Marshal for sale or use at approved locations within the City of Winchester and shall only be used on private property with the approval of the owner. Item Number Firework Device Name 0534A BUTTERFLY & FLOWER 0542 SPINNING WHEEL-12" 0623 OPEN FLOWER & HAPPY BIRD 0651 HAPPINESS FOUNTAIN 0705 PEACH FLOWER IN SPRING 0705A PEACH FLOWER IN SPRING 0705AN PEACH FLOWER IN SPRING 0710 PICCOLO PETE 0710P PICCOLO PETE 0710P-4-PDQ PICCOLO PETE 0710P-BX6 PICCOLO PETE 0750 Sparkler 0830 FRIENDSHIP FLOWERS 0830A FRIENDSHIP 0831 GOLDEN FLOWER-MEDIUM 0831A GOLDEN FLOWER-LARGE 0833 AN SMALL BUTTERFLY & FLOWERS 0833A Butterfly and Flowers 0833A BUTTERFLY & FLOWERS (LARGE) 0833A AN -

The Highland Lakes Newsette

A publication of Highland Lakes Country Club and Community Association at Highland Lakes, New Jersey © 2021 Volume 2021 | Issue Number 6 | July 3, 2021 Upcoming Summer Activities From the President’s Desk MEG WAHNON, COMMUNICATIONS COMMITTEE MICHAEL GELFAND, PRESIDENT that will require pre-registration, one being our “Kids Can If I learned nothing else throughout the course of Cook” at the Clubhouse; kids of all ages can join as long as the pandemic it’s not to take simple things—like a hug, accompanied by an adult. The second will also be a pre- a handshake, or a meal with a friend—for granted. And registration for our kids. “Pool Tournament” which will be with that in mind that I’m happy to see so much activity for children ages 10+. For your convenience, we have added in and around our community as June rolls over into July. the registration forms on our website as well as hard copies When I hear toddlers squealing with laughter at the Beach available in the clubhouse, be sure to check out the website 1 playground, see teens swimming in big groups off of the Summer! The school bell has rung which means the for our calendar. swim lane docks, and watch seniors doing embroidery work season of fun in the sun and activities in the great outdoors And it’s not all about the kids! As we do every year, together on the Seckler Stage or trash talking over at the has begun. For some parents, the summer can be stressful we have created a list of wonderful events that will be fun bocce courts at the Clubhouse Park lawn, I feel like things simply because your children will be home 24/7. -

Village of Essex Junction Trustees Regular Meeting Agenda

VILLAGE OF ESSEX JUNCTION Online & 2 Lincoln St. TRUSTEES Essex Junction, VT 05452 Tuesday, August 24, 2021 REGULAR MEETING AGENDA 6:30 PM E-mail: [email protected] www.essexjunction.org Phone: (802) 878-6951 This meeting will be held both remotely and in person. Available options to watch or join the meeting: • WATCH: the meeting will be live-streamed on Town Meeting TV. • JOIN ONLINE : Join Microsoft Teams Meeting. Depending on your browser, you may need to call in for audio (below). • JOIN CALLING: Join via conference call (audio only): (802) 377-3784 | Conference ID: 320 357 014# • PROVIDE FULL NAME: For minutes, please provide your full name whenever prompted. • CHAT DURING MEETING: Please use “Chat” to request to speak, only. Please do not use for comments. • RAISE YOUR HAND: Click on the hand in Teams to speak or use the “Chat” feature to request to speak. • MUTE YOUR MIC/TURN OFF VIDEO: When not speaking, please mute your microphone on your computer/phone. 1. CALL TO ORDER [6:30 PM] 2. AGENDA ADDITIONS/CHANGES 3. APPROVE AGENDA 4. PUBLIC TO BE HEARD a. Comments from Public on Items Not on Agenda 5. BUSINESS ITEMS a. *Work Session on Essex Junction Independence Initiative b. Consider approval of warning of first and second public hearings re: Charter for City of Essex Junction c. Consider approval of content from Our Village, Our Voices on the Village of Essex Junction website d. Consider authorizing the Village Clerk to mail out ballots to all active registered voters for the November 2nd election e. -

CLUTTER a Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University

CLUTTER A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Michael Dull May, 2018 CLUTTER Michael Dull Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Dean of Arts and Sciences Varley O’Connor Dr. John Green _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Executive Dean of Graduate School Eric Wasserman Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Date David Giffels _______________________________ Department Chair Dr. Sheldon B Wrice ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. HE’S DEAD………………………………………………………………………….....1 II. FATIGUE …………………………………………………………………………….17 III. NEW NEIGHBORS …………………………………………………………………31 IV. STANLEY AS A CHILD …………………………………………………………...53 V. RAYMOND SEES AN EXHIBIT …………………………………………………...65 VI. BREAKING UP …………………………………………………………………….77 VII. DINNER AT RAYMOND’S ………………………………………………………89 VIII. VIRGINIA’S LAST DAYS ……………………………………………………….94 IX. THE PARTY ………………………………………………………………………109 X. SPIRIT ……………………………………………………………………………..128 XI. TRYING SOMETHING NEW ……………………………………………………132 iii CHAPTER I HE’S DEAD Since it is up to me to remember, I’m afraid to admit that I’ve failed, failed because I can’t quite recall when it was that the sensations, notions, memories, facts, histories both global and personal, all came together to lead me onto pen the words I did that led to my academic disgrace and eventual “deed,” because it might have come over me while on a beach in southern Greece (a flood of black sub-Saharan faces dehydrated from Mediterranean sun), or perhaps I can think of a whiff of that old familiar feeling in Vienna when I heard the most beautiful Brahms concertos ring out from violin strings bowed by Asian hands. What I felt then, but only realize now, is that I was sensing a change in my academic obsession, my area of study, what occupied my entire adult life. -

Zigzags Holiday Program

From ay $12.32 a d child care when 85% plies, if subsidy ap O U T N O W ! eligible SUMMER SCHOOL HOLIDAY PROGRAM www.zigzagsoshc.com.au . 0421 369 516 BELDON SUMMER VACATION CARE PROGRAMME Friday 20th December 2019 – Friday 31st January 2020 Friday 20th December Monday 23rd December Tuesday 24th December Monday 6th January Tuesday 7th January Bubbles Bubbles Bubbles Rockstar for a Day Party Day! Fantasy Kingdom Krispy Kreme Decoration Day Have loads of fun with all sorts of Reveal your inner musical magic with Let’s celebrate the last day of Let your imagination go wild making Everything is better with doughnuts! bubbles. Who can make the drums, electric guitars and keyboards the Zig Zags OSHC year with your own fantasy kingdom. Best of all, you will be decorating and biggest bubbles? to play. a Party! eating them! Bubble Shooter. Geometric Bubble Wand. Rock Photo Frame. Dance like a Party Hat. Party Popper. Fantasy Creation. Doughnut Squishy. Puff Paint Doughnut. Steal the Bubble. Rockstar. Harmonica. Limbo. Dragon Stomp. Human Ring Toss. Incursion $10.00 Incursion $8.50 Incursion $5.00 Incursion $6.00 Wednesday 8th January Thursday 9th January Friday 10th January Monday 13th January Tuesday 14th January Bubble Soccer Lights, Camera, Action! Geometric Day Let’s Go Fishing AQWA Which team will win Bubble Soccer? Bump Choose from Frozen 2 (PG) or Spies in Create your own geometric painting Learn all about fishing for the future and An awesome underwater adventure and roll and play soccer all from inside a Disguise (PG) whilst enjoying some on canvas for your room catch some magnet fish in our Zig Zags awaits you at the Aquarium of giant inflatable bubble. -

Article 54. Sale, Etc., of Pyrotechnics. § 14-410. Manufacture, Sale and Use

Article 54. Sale, etc., of Pyrotechnics. § 14-410. Manufacture, sale and use of pyrotechnics prohibited; exceptions; license required; sale to persons under the age of 16 prohibited. (a) Except as otherwise provided in this section, it shall be unlawful for any individual, firm, partnership or corporation to manufacture, purchase, sell, deal in, transport, possess, receive, advertise, use, handle, exhibit, or discharge any pyrotechnics of any description whatsoever within the State of North Carolina. (a1) It shall be permissible for pyrotechnics to be exhibited, used, handled, manufactured, or discharged within the State, provided all of the following apply: (1) The exhibition, use, or discharge is at a concert or public exhibition. (2) All individuals who exhibit, use, handle, or discharge pyrotechnics in connection with a concert or public exhibition have completed the training and licensing required under Article 82A of Chapter 58 of the General Statutes. The display operator or proximate audience display operator, as required under Article 82A of Chapter 58 of the General Statutes, must be present at the concert or public exhibition and must personally direct all aspects of exhibiting, using, handling, or discharging the pyrotechnics. Notwithstanding this subdivision, the display operator for the University of North Carolina School of the Arts may appoint an on-site representative to supervise any performances that include a proximate audience display subsequent to the opening performance, provided that the representative (i) is a minimum of 21 years of age and (ii) is properly trained in the safe discharge of proximate audience displays. (3) The display operator has secured written authority under G.S. -

This Week in the Susquehanna River Valley December 18-28, 2019 This Is Just a Sampling of Events This Week

This Week in the Susquehanna River Valley December 18-28, 2019 This is just a sampling of events this week. For many more events, go to www.VisitCentralPA.org and click on “Events” ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT December 18-28: Events this Week at Your Campus Theatre JoJo Rabbit (12/19) JoJo Rabbit is about a young boy living during World War II. His only escapism is through his imaginary friend, an ethnically inaccurate version of Adolf Hitler, who pushes the young boy’s naive patriotic beliefs. The Good Liar (12/20-23) A career con man sets his sights on his latest mark: a widow worth millions. And he means to take it all. But as the two draw closer, what should have been another simple swindle takes on the ultimate stakes. The Black Candle (12/26) A documentary about the struggle and triumph of African American family, community, and culture, using Kwanzaa as a vehicle to celebrate the African American experience. Parasite (12/27-29) South Korean black comedy thriller film. Free Holiday Film Series: A Christmas Story (12/21) and It’s a Wonderful Life (12/22). A non-perishable food donation is suggested for each screening. Santa will visit the theatre on Dec. 21 and there will be a Bike Giveaway before the movie. For more information and movie times visit www.CampusTheatre.org Lewisburg December 20: Holiday Jazz with the WCJO at the Community Theatre League The Williamsport City Jazz Orchestra returns to the CTL Mainstage for an evening of holiday tunes with a jazzy spin. www.ctlshows.com Williamsport December 21-22: Buffalo Valley Singers Christmas Concert “Christmas is Coming" The Buffalo Valley Singers will present a Christmas concert on Saturday Dec. -

M a R G a R I T a V Ille

MARGARITAVILLE® COCONUT TELEGRAPH ® VOLUME 29 NO.2 SPRING 2013 WWW.MARGARITAVILLEKEYWEST.COM a b d c a Ladies Tie-dye Tank Top Rib knit ladies tank top, 100% cotton. Colors may vary on this allover print. S #22910, M #22911, L #22912, XL #22913 $25.95 b It’s 5:00 Somewhere Tin Sign Colorful realistic Parrot with tropical background, measures approx. 17.5” x 11.5” #10438 $24.95 c University of Margaritaville Bar & Lounge Cap Colorful detailed design embroidered on front with Parrot overlapping on the brim. Key West embroidered on back over closure. Red #10305 $18.00 d Margaritaville Ladies Tank Iconic Parrot & Sunset logo on 100% smooth ring spun cotton tank top. Double stitched neck, sleeves and waist. Turquoise Blue S #22591, M #22592, L #22593, XL #22594 $21.95 e XXL #22595 $22.95 e Tie-dye bottle skin with a twist It is the PARTY POPPER, the all-in-one Neoprene Koozie Bottle Insulator & opener. Featuring a built-in bottle opener and heavy-duty Neoprene Koozie, this great new item pops your top and keeps your beverage cold. It’s sure to keep your drink cool and make you the life of the party. Peace, Love Margaritaville Key West screened on one side. 1 #1227 $8.95 But there’s this one particular harbour a b FRONT LEFT POCKET c a Just a Son of a Sailor Pocket T’ Pocket tee with sailing design. Garment dyed. Blue M #22667, L #22668, XL #22669 $25.95 XXL #22670 FRONT LEFT CHEST $26.95 3XL #22671 $27.95 b Boat Drinks Camp Shirt Margaritaville Lifestyle Brand - Washed in the ocean, Dried in the Sun. -

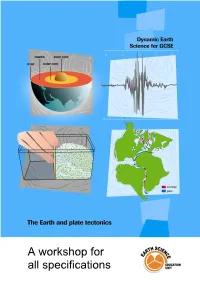

A Workshop for All Specifications

A workshop for all specifications With the support of: Workshop prepared by: Paul Baggaley, Susan Beale, Dee Edwards, Peter Kennett, Phillip Murphy, Dave Turner, Royanne Wilding Edited by: Chris King, Susie Lydon, Cally Oldershaw, Peter Kennett and Hazel Benson © The Earth Science Education Unit Copyright is waived for original material contained in this booklet if it is required for use within the laboratory or classroom. Copyright material contained herein from other publishers rests with them. Every effort has been made to locate and contact copyright holders of materials included in this document in order to obtain their permission to publish them. Please contact us if, however, you believe your copyright is being infringed: we welcome any information that will help us to update our records. If you have any difficulty with the readability of these documents, please contact the Earth Science Education Unit for further help. The Earth Science Education Unit School of Public Policy and Professional Practice, Chancellors Building, Keele University, Keele, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG Tel: 01782 734437 Fax: 01782 734438 Email: [email protected] http://www.earthscienceeducation.com ESEU KS4 Workshops: The Earth and Plate Tectonics Contents Workshop outcomes ....................................................................................................................... 2 The Story for Teachers: Plate Tectonics ......................................................................................... 4 The big picture and the ‘facts’ of plate -

City Council Meeting Agenda Tuesday, November 26, 2019

CITY COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 26, 2019 LOCATION: NOTE: Regular and Special Sessions are City Administration Building open to the public. Executive Sessions City Council Chambers are closed to the public. There is an 107 E. Main Street opportunity for Audience Comments Xenia, OH 45385 during Regular Sessions only. Regular Session 1. CALL TO ORDER 6:00 p.m. 2. INVOCATION Charlie Huff 3. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Councilman Levi Dean 4. ROLL CALL Vice President Edgar Wallace, Councilman Will Urschel, Councilman Dale Louderback, Councilman Wesley Smith, Councilman Levi Dean, Mayor Sarah Mays, and President Michael Engle 5. APPROVAL OF MINUTES November 5, 2019, Special Session November 14, 2019, Regular Session 6. SPECIAL PRESENTATION(S) None. 7. AUDIENCE COMMENTS (Time limit may be imposed by the Chair. Those who wish to speak must sign in and state their names/addresses for the record.) 8. OLD BUSINESS A. ORDINANCE 2019-22 AMENDING CHAPTER 678 AND SECTIONS 448.03, 618.11, (Second Reading) AND 1062.03, AND REPEALING CHAPTER 604, AND ITS RELATED PROVISIONS, OF THE CITY OF XENIA CODIFIED ORDINANCES TO COMPLY WITH OHIO REVISED CODE SECTION 9.68 Introduced by Councilman Dean on 11/14/19 9. PUBLIC HEARING(S) A. ORDINANCE 2019-23 VACATING A SECTION OF A SIX-FOOT WIDE PUBLIC (Introduction) ALLEY RIGHT-OF-WAY PARALLEL TO STELTON ROAD AND ABUTTING LOTS 1, 2, AND 3 OF THE MILLER ADDITION SUBDIVISION AND LOT 1A OF THE SOLS ADDITION REPLAT (City Manager) 10. NEW BUSINESS A. ORDINANCE 2019-24 AMENDING ORDINANCE 2019-20 TO PROVIDE (Emergency) APPROPRIATIONS FOR CURRENT EXPENSES AND OTHER EXPENDITURES FOR THE CITY OF XENIA, OHIO, FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 31, 2019, AND DECLARING AN EMERGENCY (Finance Director) B.