Exploring the Decision Making of Immigration Officers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bloomsbury Professional

Immigration Asylum 24_2 cover.qxp:Layout 1 16/6/10 09:42 Page 1 Related Titles from Bloomsbury Professional JOURNAL of Immigration Law and Practice, 4th edition 24 Number 2 2010 Journal of Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Law Volume IMMIGRATION By David Jackson, George Warr, Julia Onslow-Cole & Joseph Middleton Reverting to hardback format, the fourth edition of this clear and practical book has been thoroughly updated by a team of specialist practitioners. It deals comprehensively with ASYLUM AND immigration law procedure and practice, covering European and human rights law, deportation, asylum and onward appeals. In this continually evolving area of law, this fourth edition takes into account all recent NATIONALITY major legislation changes and developments, relevant case law and policies since the last edition. ISBN: 978 1 84592 318 1 Price: £120 Format: Hardback LAW Pub date: Dec 2008 Asylum Law and Practice, 2nd edition Volume 24 Number 2 2010 Pages 113–224 By Mark Symes and Peter Jorro Written by two of the leading authorities on the law relating to asylum, Asylum Law and EDITORIAL Practice, 2nd edition is a detailed exposition of the law relating to asylum and NEWS international protection. ARTICLES Bringing together in one volume, all relevant aspects of asylum law and practice in the The Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 United Kingdom, this book is comprehensive enough to serve as a reliable source of Alison Harvey information and analysis to all asylum practitioners. Its depth, thoroughness, and clarity make it a must have for all practitioners. Victims of Human Trafficking in Ireland – Caught in a Legal Quagmire The book is focused on the position in the UK, but with reference to refugee law cases in Hilkka Becker other jurisdictions; such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the USA. -

The Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 (Jersey) Order 2003

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2003 No. 1252 IMMIGRATION The Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 (Jersey) Order 2003 Made - - - - - 8th May 2003 Coming into force - - 5th June 2003 At the Court at Buckingham Palace, the 8th day of May 2003 Present, The Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty in Council Her Majesty, in exercise of the powers conferred upon Her by section 36 of the Immigration Act 1971(a) and section 170(7) of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999(b), is pleased, by and with the advice of Her Privy Council, to order, and it is hereby ordered, as follows:— 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 (Jersey) Order 2003 and shall come into force on 5th June 2003. (2) In this Order— “the 1971 Act” means the Immigration Act 1971, and “Jersey” means the Bailiwick of Jersey. (3) For the purposes of construing provisions of the 1971 Act as part of the law of Jersey, any reference to an enactment which extends to Jersey shall be construed as a reference to that enactment as it has eVect in Jersey. 2. The provisions of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 which are specified in the left- hand column of the Schedule to this Order shall extend to Jersey subject to the modifications specified in relation to those provisions in the right-hand column of that Schedule, being such modifications as appear to Her Majesty to be appropriate. 3. The Immigration (Jersey) Order 1993(c) shall be varied as follows— (a) at the end of article 4(1), insert “and section 20(2) of the Interpretation Act 1978 shall apply for the interpretation of this Order as it applies for the interpretation of an Act of Parliament.”; (b) for the modification of “Committee” made by paragraph 18(a)(i) of Schedule 1 to that Order, substitute— ““Committee” means the Home AVairs Committee of the States”. -

Information About Becoming a Special Constable

Citizens in Policing #DCpoliceVolunteers Information about becoming a Special Constable If you would like to gain invaluable experience and support Devon & Cornwall Police in making your area safer join us as a Special Constable Contents Page Welcome 4 Benefits of becoming a Special Constable 6 Are you eligible to join? 7 Example recruitment timeline 10 Training programme 11 Frequently asked questions 13 Information about becoming a Special Constable 3 Welcome Becoming a Special Constable (volunteer police officer) is your Becoming a volunteer Special Constable is a great way for you chance to give something back to your community. Everything to make a difference in your community, whilst at the same time you do will be centred on looking after the community, from developing your personal skills. Special Constables come from all businesses and residents to tourists, football supporters and walks of life but whatever your background, you will take pride from motorists. And you’ll be a vital and valued part of making Devon, giving something back to the community of Devon and Cornwall. Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly safer. We are keen to use the skills you can bring. In terms of a volunteering opportunity, there’s simply nothing We have expanded the roles that Special Constables can fulfil, with else like it. Special Constables work on the front line with regular posts for rural officers, roads policing officers and public order police officers as a visible reassuring presence. As a Special officers all coming on line. I am constantly humbled and inspired by Constable you will tackle a range of policing issues, whether that the commitment shown by Special Constables. -

Response by the Immigration Law Practitioners Association 28 July 2006

Response by the Immigration Law Practitioners Association 28 July 2006: Consultation Document: Private freight searching and fingerprinting at Juxtaposed Controls Introduction ILPA is a professional association with some 1200 members, who are barristers, solicitors and advocates practising in all aspects of immigration, asylum and nationality law. Academics, non-government organisations and others working in this field are also members. ILPA exists to promote and improve the giving of advice on immigration and asylum, through teaching, provision of high quality resources and information. ILPA is represented on numerous government and appellate authority stakeholder and advisory groups. We are grateful for this opportunity to express our concerns regarding the proposed extension of UK activities in France and Belgium regarding the detention and fingerprinting of individuals and the extension of UK powers of detention to companies acting in France and Belgium. ILPA provided briefings to parliamentarians and also discussed with Ministers and officials what are now sections 41 and 42 of the Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006 and also the fingerprinting provisions of the 2006 Act and its predecessors. We have drawn attention in this response to comments made by Ministers at the time, which could usefully have been discussed more extensively in the consultation paper itself. We have looked at the questions posed in the consultation paper. Given that many of them are directed at those operating in the ports concerned we have not structured our response around those questions. We have, however, highlighted them where appropriate. Our concerns revolve primarily around two aspects of the legislation and its proposed implementation: (1) Private contractors will be given the power to search vehicles and any person to detect and to detain and escort such persons to the nearest immigration detention facility. -

In the Supreme Court of Tennessee at Nashville

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE AT NASHVILLE _______________________________________ ) DANIEL RENTERIA-VILLEGAS, ) DAVID ERNESTO GUTIERREZ- ) TURCIOS, and ROSA LANDAVERDE, ) ) Plaintiffs-Movants, ) ) v. ) M2011-02423-SC-R23-CQ ) METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT OF ) Trial Court No. 3:11-cv-218 (M.D. Tenn.) NASHVILLE AND DAVIDSON COUNTY, ) and UNITED STATES IMMIGRATION ) AND CUSTOMS ENFORCEMENT, ) ) Defendants-Respondents. ) _______________________________________) PLAINTIFFS’ REPLY BRIEF ON CERTIFICATION FROM THE U.S. DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE Elliott Ozment Trina Realmuto R. Andrew Free NATIONAL IMMIGRATION PROJECT OF THE IMMIGRATION LAW OFFICES NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD OF ELLIOTT OZMENT 14 Beacon Street, Suite 602 1214 Murfreesboro Pike Boston, MA 02108 Nashville, Tennessee 37217 William L. Harbison Thomas Fritzsche Phillip F. Cramer Daniel Werner SHERRARD & ROE, LLC Immigrant Justice Project 150 3rd Avenue S., Suite 1100 SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER Nashville, Tennessee 37201 233 Peachtree St. NE, Suite 2150 Atlanta, GA 30303 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iv I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 II. ARGUMENT ..................................................................................................................... -

Wales-And-Sw.Pdf

THE UK BORDER AGENCY RESPONSE TO THE CHIEF INSPECTOR’S REPORT ON OPERATIONS IN WALES AND THE SOUTH WEST OF ENGLAND THE UK BORDER AGENCY RESPONSE TO RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE CHIEF INSPECTOR’S REPORT ON OPERATIONS IN WALES AND THE SOUTH WEST OF ENGLAND The UK Border Agency thanks the Independent Chief Inspector for this report, and for his comments again about the enthusiasm and commitment of our staff, who deal with the challenges of their roles with professionalism. The Wales and South West of England was the first geographical area to be chosen for this type of inspection, and we valued the opportunity this snapshot in time presented to us as a lever for improvement. Sine the inspection we have been implementing many of the recommendations but there is of course much more to be done and we welcome the opportunity of presenting our proposals here. We are pleased the inspection recognises that we have done a lot since regionalisation and the bringing together of immigration and customs functions at the border. The Agency welcomes the recommendations to further improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the operations in Wales and the South West of England. The recommendations are that the Agency: 1. Ensures targets and priorities are made clear to all staff, and introduces working practices to minimise possible conflicts and maximise cross-functional working. 1.1 The UK Border Agency accepts this recommendation. 1.2 The Chief Inspector has acknowledged that in Immigration Group regional targets are clearly set out in the regional Business Plan which has been issued to all staff. -

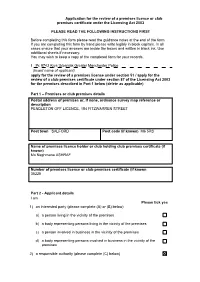

Application for the Review of a Premises Licence Or Club Premises Certificate Under the Licensing Act 2003

Application for the review of a premises licence or club premises certificate under the Licensing Act 2003 PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING INSTRUCTIONS FIRST Before completing this form please read the guidance notes at the end of the form. If you are completing this form by hand please write legibly in block capitals. In all cases ensure that your answers are inside the boxes and written in black ink. Use additional sheets if necessary. You may wish to keep a copy of the completed form for your records. I Pc 8743 Krys Urbaniak Greater Manchester Police (Insert name of applicant) apply for the review of a premises licence under section 51 / apply for the review of a club premises certificate under section 87 of the Licensing Act 2003 for the premises described in Part 1 below (delete as applicable) Part 1 – Premises or club premises details Postal address of premises or, if none, ordnance survey map reference or description PENDLETON OFF LICENCE, 154 FITZWARREN STREET Post town SALFORD Post code (if known) M6 5RS Name of premises licence holder or club holding club premises certificate (if known) Ms Naghmana ASHRAF Number of premises licence or club premises certificate (if known 35225 Part 2 - Applicant details I am Please tick yes 1) an interested party (please complete (A) or (B) below) a) a person living in the vicinity of the premises b) a body representing persons living in the vicinity of the premises c) a person involved in business in the vicinity of the premises d) a body representing persons involved in business in the vicinity of -

Immigration Act

LAWS OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO IMMIGRATION ACT CHAPTER 18:01 Act 41 of 1969 Amended by 7 of 1974 *24 of 1978 *47 of 1980 *19 of 1988 37 of 1 995 *(See Notes on page 2) Current Authorised Pages Pages Authorised (inclusive) by L.R.O. I -2/1 L.R.O. 1/ LAWS OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Index of Subsidiary Legislation Page Immigration Regulations (G.N. 178/1974) 47 Note on Subsidiary Legislation The Classes of Undesirable Immigrants Order 1953 (G.N. 177/1953 as amended), the Immigration Detention Places Regulations (1950 Ed. Vol. Vill page 801) and the Notice fixing Overtime rates for Launch Crews (R.G. 13.1.1921, as amended) made under the Immigration (Restriction) Ordinance. Chapter 20 No.2 (1950 Ed.) (now repealed) continue in force by virtue of section 29(3) of the Interpretation Act (Ch. 3:01). but they have not been published as they are out of date and will soon be revoked or replaced. Similarly, orders made under section 4 of the repealed Ordinance declaring specified persons to be undesirable immigrants have not been published since they are of a personal nature. Note on Act No.19 of 1988 Section 38 of the Trinidad and Tobago Free Zones Act, 1988 (Act No. 19 of 1988) provides as follows: Work permits. 38. (1) A person who is a foreign national or Commonwealth citizen employed by the Company or by an approved enterprise established in any free zone shall not, by virtue only of such employment, be exempt from the Immigration Act, but the Minister responsible for the administration of that Act shall, in considering applications by or on behalf of such a person. -

Border, Immigration & Citizenship System Policy And

Border, Immigration & Tel: 020 7035 4848 Citizenship System Policy Fax: 020 7035 4745 and Strategy Group www.gov.uk/homeoffice ( BICS PSG) 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF By Email: FOI Reference: 41250 Date: 28 April 2017 Dear Thank you for your e-mail of 28 September 2016 in which you ask for a total figure for the amount of money the UK Government has spent since 2010 on deterring illegal immigration in Calais and the surrounding region, including a breakdown on the measures this has been used to fund. I am sorry for the delay in responding. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. Your question and the response to it is outlined below. “I want to know how much the Government has spent since 2010 to deter illegal immigration in Calais and the surrounding region. I would like a total figure in pounds and a detailed breakdown on the measures this has been used to fund.” I can confirm that the total investment in border security at the juxtaposed controls in the Calais area includes day to day activity such as carrying out passport checks on all passengers, searching for illicit goods, as well as stopping and deterring illegal migration. It also includes the recent investment to reinforce security through infrastructure improvements at Border Force’s controls in Northern France as well as wider activity by the Home Office and its partners, including the National Crime Agency, to stop and deter illegal migration in the Calais region. This investment is set out in Annex A. -

2019 Senate Bill 401

2019 - 2020 LEGISLATURE LRB-3782/2 EAW&MES:amn&kjf 2019 SENATE BILL 401 September 16, 2019 - Introduced by Senators LARSON, L. TAYLOR, SMITH and JOHNSON, cosponsored by Representatives CABRERA, BROSTOFF, HAYWOOD and BOWEN. Referred to Committee on Insurance, Financial Services, Government Oversight and Courts. 1 AN ACT to create 59.26 (11), 66.0112 and 165.57 of the statutes; relating to: 2 limiting the cooperation of state and local law enforcement officers with certain 3 federal immigration enforcement activities. Analysis by the Legislative Reference Bureau This bill limits the extent to which the Department of Justice and local law enforcement officers may cooperate with federal immigration enforcement activities. Under the bill, DOJ may not authorize a state or local law enforcement officer to assist a federal immigration officer in immigration enforcement activities, and the department must publish a model policy for local governments to adopt on limiting assistance with such activities. The bill defines “immigration enforcement” as any action taken by federal or state or local law enforcement officers related to the investigation or enforcement of any federal civil immigration law or any federal criminal immigration law that penalizes an individual's presence in, entry or reentry to, or employment in the United States. Also under the bill, no city, village, town, or county (political subdivision) may authorize or permit its law enforcement officers to assist a federal immigration officer in immigration enforcement activities, nor -

The Role of Local Police: Striking a Balance Between Immigration Enforcement and Civil Liberties

The Role of Local Police: Striking a Balance Between Immigration Enforcement and Civil Liberties by Anita Khashu April 2009 Washington, DC The Police Foundation is a national, nonpartisan, nonprofit organization dedicated to support - ing innovation and improvement in policing. Established in 1970, the foundation has conducted seminal research in police behavior, policy, and procedure, and works to transfer to local agen - cies the best information about practices for dealing effectively with a range of important police operational and administrative concerns. Motivating all of the foundation’s efforts is the goal of efficient, humane policing that operates within the framework of democratic principles and the highest ideals of the nation. ©2008 by the Police Foundation. All rights, including translation into other languages, reserved under the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, and the International and Pan American Copyright Conventions. Permission to quote is readily granted. ISBN 1-884614-23-X 978-1-884614-23-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009924868 1201 Connecticut Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036-2636 (202) 833-1460 voice (202) 659-9149 fax [email protected] www.policefoundation.org An executive summary and the full report of The Role of Local Police: Striking a Balance Between Immigration Enforcement and Civil Liberties are available online at http://www.policefoundation.org/strikingabalance/. ii | THE ROLE OF LOCAL POLICE: Striking a Balance Between Immigration Enforcement and Civil Liberties Table of Contents Contributors . vi Foreword . vii Acknowledgments . x Executive Summary . xi About the Project . : History of the Role of Local Police in Immigration Enforcement . -

Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 (Guernsey) Order 2003

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2003 No. 2900 IMMIGRATION The Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 (Guernsey) Order 2003 Made - - - - - 13th November 2003 Coming into force - - 11th December 2003 At the Court at Buckingham Palace, the 13th day of November 2003 Present, The Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty in Council Her Majesty, in exercise of the powers conferred upon her by section 170(7) of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999(a), is pleased, by and with the advice of Her Privy Council, to order, and it is hereby ordered, as follows: 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 (Guernsey) Order 2003 and shall come into force on 11th December 2003. (2) In this Order— “the 1971 Act” means the Immigration Act 1971(b); and “Guernsey” means the Bailiwick of Guernsey. (3) For the purposes of construing provisions of the 1971 Act as part of the law of Guernsey, any reference to an enactment which extends to Guernsey shall be construed as a reference to that enactment as it has eVect in Guernsey. 2. The provisions of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 which are specified in the left- hand column of the Schedule to this Order shall extend to Guernsey subject to the modifications specified in relation to those provisions in the right-hand column of that Schedule, being such modifications as appear to Her Majesty to be appropriate. 3. The Immigration (Guernsey) Order 1993(c) shall be varied by inserting at the end of article 4(1), “and section 20(2) of the Interpretation Act 1978 shall apply for the interpretation of this Order as it applies for the interpretation of an Act of Parliament”.