The London Gazette of 1 October 1666 Announced That Two Days Previously

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London's Soap Industry and the Development of Global Ghost Acres

London’s Soap Industry and the Development of Global Ghost Acres in the Nineteenth Century John Knight won a prize medal at the Great Exhibition in 1851 for his soaps, which included an ‘excellent Primrose or Pale-yellow-soap, made with tallow, American rosin, and soda’.1 In the decades that followed the prize, John Knight’s Royal Primrose Soap emerged as one of the United Kingdom’s leading laundry soap brands. In 1880, the firm moved down the Thames from Wapping in East London to a significantly larger factory in West Ham’s Silvertown district.2 The new soap works was capable of producing between two hundred and three hundred tons of soap per week, along with a considerable number of candles, and extracting oil from four hundred tons of cotton seeds.3 To put this quantity of soap into context, the factory could manufacture more soap in a year than the whole of London produced in 1832.4 The prize and relocation together represented the industrial and commercial triumph of this nineteenth-century family business. A complimentary article from 1888, argued the firm’s success rested on John Knights’ commitment ‘to make nothing but the very best articles, to sell them at the very lowest possible prices, and on no account to trade beyond his means’.5 The publication further explained that before the 1830s, soap ‘was dark in colour, and the 1 Charles Wentworth Dilke, Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851: Catalogue of a Collection of Works On, Or Having Reference To, the Exhibition of 1851, 1852, 614. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Glaven Historian

the GLAVEN HISTORIAN No 16 2018 Editorial 2 Diana Cooke, John Darby: Land Surveyor in East Anglia in the late Sixteenth 3 Jonathan Hooton Century Nichola Harrison Adrian Marsden Seventeenth Century Tokens at Cley 11 John Wright North Norfolk from the Sea: Marine Charts before 1700 23 Jonathan Hooton William Allen: Weybourne ship owner 45 Serica East The Billyboy Ketch Bluejacket 54 Eric Hotblack The Charities of Christopher Ringer 57 Contributors 60 2 The Glaven Historian No.16 Editorial his issue of the Glaven Historian contains eight haven; Jonathan Hooton looks at the career of William papers and again demonstrates the wide range of Allen, a shipowner from Weybourne in the 19th cen- Tresearch undertaken by members of the Society tury, while Serica East has pulled together some his- and others. toric photographs of the Billyboy ketch Bluejacket, one In three linked articles, Diana Cooke, Jonathan of the last vessels to trade out of Blakeney harbour. Hooton and Nichola Harrison look at the work of John Lastly, Eric Hotblack looks at the charities established Darby, the pioneering Elizabethan land surveyor who by Christopher Ringer, who died in 1678, in several drew the 1586 map of Blakeney harbour, including parishes in the area. a discussion of how accurate his map was and an The next issue of Glaven Historian is planned for examination of the other maps produced by Darby. 2020. If anyone is considering contributing an article, Adrian Marsden discusses the Cley tradesmen who is- please contact the joint editor, Roger Bland sued tokens in the 1650s and 1660s, part of a larger ([email protected]). -

The London Gazette, January 3, 1899, 15

THE LONDON GAZETTE, JANUARY 3, 1899, 15 Commencement. December 29, 1898., • 2. This Order shall come into operation on the AFTER OPEN COMPETITION. tenth day of January, one thousand eight hundred Post Office: Woman Clerk, Ruth Emma Soothill. and ninety-nine. Female Sorter, London, Violette Frances In witness whereof the Board of Agriculture Bishop. have hereunto set their Official Seal this WITHOUT COMPETITION. second day of January, one thousand Prisons Department, England: Assistant Matrons, eight hundred and ninety-nine. Lucy Matilda Limbrick, Elizabeth Ann Thomas. • T. H. Elliott, Prisons Department, Scotland: Female Warder^ Secretary. Lily Gray. Post Office: Postmen, London, Herbert John Clow, Albert Pedder. •-...-. Porter, London, Thomas Park. SCHEDULE. Postman, Edinburgh, Alexander Valentine. Districts to which this Order applies. Postmen, Birmingham, Arthur Henry Hill- County of Kent man, Arthur Russell. - . ' Borough of Canterbury. December 30, 1898. _, Borough of Chatham. Borough of Dover. AFTER OPEN COMPETITION. Borough of Folkestone. Post Office: Male Sorter, London, John Maguire. Borough, of Gravesend. AFTER LIMITED COMPETITION. Borough of Maidstone. Foreign Office: Attache" in Her Majesty's Diplo- Borough of Rochester. matic Service or Clerk on the Establishment^ Borough of Tunbridge WelLs. Godfrey Tennyson Lampson Lockef-Lampson. WITHOUT COMPETITION. Copies of the above Order can be obtained on Inland Revenue: Stamper, John'Cooper. - application to the Secretary, Board of Agriculture, 4, Whitehall Place, London, S.W. Post -

The London Gazette, 3 June, 1924

4504 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 3 JUNE, 1924. BYRNE, Annie ^Married Woman), residing and TETLOW, Harry, residing and carrying ore carrying on business at 749, Stockport-road, business at 142 and 144, Castleton-roadr Longsight. Manchester. LADIES' TAILOR Royton, in the county of Lancaster. and COSTUMIER. BUTCHER. Court—MANCHESTER. Court—OLDHAM. No. of Matter—92 of 1923. No. of Matter—31 of 1923. Trustee's Name, Address and Description— Trustee's Name, Address and Description— Gibson, John Grant, Byrom-street, Man- Gibson, John Grant, Byrom-^street, Man- chester, Official Receiver. chester, Official Receiver. Date of Release—May 26, 1924. Date of Release—.May 26, 1924. DAY, Walter James, residing at 34, Meal-street, SMITH, Fred, Cleavers Lodge, Covington, in the- New Mills, in the county of Derby, and carry- county of Northampton. FARMER. ing on business at 1, Poplar-street, Viaduct- Court—PETERBOROUGH. street, Ardwick, Manchester, in the county of No. of Matter—17 of 1923. Lancaster. Wholesale SWEETS and CHOCO- Trustee's Name, Address and Description— LATE MERCHANT. Morris, J. Osborne, 5, Petty Cury, Cambridge, Court—MANCHESTER. Official Receiver. No. of Matter—79 of 1923. Date of Release—May 26, 1924. Trustee's Name, Address and Description— Gibson, John Grant, Byrom-street, Man- LITCHFIELD, Arthur, residing at 2, Littlewood- chester, Official Receiver. street, Pendleton, Manchester; WARREN, Date of Release—May 26, 1924. Harrv Howarth, residing at 262, Ordsall-lane, Salf ord; and ARMITT, Ernest, residing at 120, Fitzwarren-street, Pendleton, Manchester, and SLATER, Thomas Gascoigne, residing at 47, lately carrying on business in co-partnership^ Greenhill-road, Cheetham Hill, Manchester, together, under the style of SEALED BREAD and carrying on business as SLATER BAKERY, at Elizabeth-street. -

The London Gazette

No. 44995 12867 The London Gazette Registered as a Newspaper CONTENTS PAGE PAGE STATE INTELLIGENCE . 12867 Partnerships ... 12913 PUBLIC NOTICES .... 12876 Changes of Name .... 12913 LEGAL NOTICES Next of Kin None Miscellaneous . ' . 12914 . 12892 Marriage Acts ..... Board of Trade Notices under the Bankruptcy Building Societies Act . None Acts and the Companies Acts . 12914 Friendly Societies Act . 12892 LATE NOTICES . .12926-12928 Industrial and Provident Societies Acts 12892 The Trustee Act, 1925 12929 r Companies Act, 1948 .... 12893 SCALE OF CHARGES ....12946 MONDAY, 22ND DECEMBER 1969 State Intelligence BY THE QUEEN the date 1971, or of a succeeding year, and for the reverse the badge of the Prince of Wales, being A PROCLAMATION three ostrich feathers entiling a coronet of crosses DETERMINING THE SPECIFICATIONS AND DESIGN FOR, pattee and fleurs de lys with the motto " ICH AND GIVING CURRENCY TO, CUPRO-NICKEL AND DIEN", and the inscription "2 NEW PENCE". BRONZE COINS IN GIBRALTAR. The coin shall have a plain edge. (2) New penny—Every new penny shall have the ELIZABETH R. same obverse impression and inscription as the two We, in exercise of the powers conferred by section new pence, and for the reverse a portcullis with 11 of the Coinage Act 1870, as extended by section chains royally crowned, being a badge of King Henry 2 (3) and (4) of the Decimal Currency- Act 1967, VII and his successors, and the inscription " 1 NEW and of all other powers enabling- Us in that behalf, PENNY ". The coin shall have a plain edge. do hereby, by and with the advice of Our Privy (3) New halfpenny—Every new halfpenny shall Council, proclaim, direct and ordain as follows: have the same obverse impression and inscription as 1. -

1660 Supplement to the London Gazette, February. 27, 1878

1660 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, FEBRUARY. 27, 1878. THE NATIONAL BANK OF SCOTLAND—continued. Name, Residence, Occupation. Name, Residence, Occupation. Learmonth, Alexander, Falkirk, Flesher Mai-shall, John D., Edinburgh, Jeweller Leask, John, Burnside, of Chivas, Farmer Marshall, James, and spouse, Edinburgh, Merchant Lee, Mrs. E. Cbiene or, Roxburgh Manse, Kelso Marshall, Mrs. S. PI. Murray or, and children, Lee, Rev. William, Roxburgh Manse, D.I). Trustees of Lee.*, Mrs. M., Trustees of, for Mrs. Stewart, and Martini Benefit Fund Trustees others Mason, Miss Isabella, Glasgow Lees, Mrs. M.; Trustees of, for Miss E. Haig, Mason, Miss A. H., Jedburgh and others Maule, the Lady Christian, Linlithgow. Lees, Robert, Let-brae, Galashiels Maxton, Trustees for behoof of Poor of Parish of Legat, Miss Isabella, Musselburgh- Maxton/J'osiah, Executors of, Edinburgh, Saddler Legat, Miss Margaret, Musselburgh Maxwell, Waller, Langholm, Farmer Leggat, Miss Margaret, Glasgow May, Mrs. B. G. S. Wishart or, Croydon Lennox, Peter, Helensburgh Medical, Royal. Society, Edinburgh Lennox, Mrs. I. M'Alister or. Glasgow Meikle, Rev. Gilbert, Inverary Leslie, Misses C. and E., and survivor, Helens- Meikle, Rev. Gilbert, and Mrs. Ann Stark, in burgh trust, -Inverary Leslie, Miss C., Edinburgh Meldrum, George, Executors of, Kirkcaldy Leslie. Miss J., Edinburgh Meldrum, Mrs. Mary Calder Rymer or, Burntisland Lesslie, Alexander, Kirkcaldy, Farmer Melville, Mrs. M., Executors of, Kirkcudbright Lewis, Miss Janet, Dumfries Mf-nzies, Miss Ann, Crieff Liechtenstein, Georgp, Edinburgh, Music Teacher Menzies, Executrix of Duncan, Glasgow, Baker Liddell, Mrs. G. K. Wishart or, Sheffield Mciizies, Mi*s J., Executrix of, Edinburgh Liddell, John, Edinburgh Meuzies, John, Edinburgh, Bookseller Lidgate, John, Edinburgh Meuzies, Fletcher Norton, Edinburgh Lidgate, John, Edinburgh, S.S.C. -

The London Gazette of TUESDAY, the Itfh of OCTOBER, 1947 by Registered As a Newspaper

38098 4847 SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette Of TUESDAY, the itfh of OCTOBER, 1947 by Registered as a newspaper THURSDAY, 16 OCTOBER, 1947 SINKING OF THE GERMAN BATTLESHIP 3. Early on 2ist May a report was received BISMARCK ON 27™ MAY, 1941. of ii merchant vessels and. 2 heavily-screened large warships -northbound in the Kattegat the The following Despatch was submitted to the day before. Later in the day the warships Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty on the were located at Bergen and identified from air $th July, 1941, by Admiral Sir JOHN C. • photographs as one Bismarck class battleship TOVEY, K.C.B., D.S.O., Commander-in- and one Hipper class cruiser. There were in- Chief, Home Fleet. dications that these two were contemplating a Home Fleet, raid on the ocean trade routes (Admiralty . 3th July, 1941. message 1828/2ist May) though, if this were so, it seemed unlikely that they would stop at a Be pleased to lay before the Lords Commis- place so convenient for air reconnaissance as sioners of the Admiralty the following despatch Bergen. Two other .pointers were a report (un- covering the operations leading to the sinking reliable) of a U-boat, north of Iceland, and an of the German battleship BISMARCK on attack 'by a German aircraft on Thorshaven Tuesday, 27th May, 1941. All times are zone W/T station. minus 2. 4. The following dispositions were made: — First Reports of Enemy. (a] HOOD (Captain Ralph Kerr, C.B.E.), 2. In the second week of May an unusual flying the flag of Vice-Admiral Lancelot E. -

LONDON the DORCHESTER Two Day Itinerary: Old Favourites When It Comes to History, Culture and Architecture, Few Cities Can Compete with London

LONDON THE DORCHESTER Two day itinerary: Old Favourites When it comes to history, culture and architecture, few cities can compete with London. To look out across the Thames is to witness first-hand how effortlessly the city accommodates the modern while holding onto its past. Indeed, with an abundance of history to enjoy within its palaces and museums and stunning architecture to see across the city as a whole, exploring London with this one-day itinerary is an irresistible prospect for visitors and residents alike. Day One Start your day in London with a visit to Buckingham Palace, just 20 minutes’ walk from the hotel or 10 minutes by taxi. BUCKINGHAM PALACE T: 0303 123 7300 | London, SW1A 1AA Buckingham Palace is the 775-room official residence of the Royal Family. During the summer, visitors can take a tour of the State Rooms, the Royal Mews and the Queen’s Gallery, which displays the Royal Collection’s priceless artworks. Changing the Guard takes place every day at 11am in summer (every other day in winter) for those keen to witness some traditional British pageantry. Next, walk to Westminster Abbey, just 15 minutes away from the Palace. WESTMINSTER ABBEY T: 020 7222 5152 | 20 Dean’s Yard, London, SW1P 3PA With over 1,000 years of history, Westminster Abbey is another London icon. Inside its ancient stone walls, 17 monarchs have been laid to rest over the course of the centuries. Beyond its architectural and historical significance, the Abbey continues to be the site in which new monarchs are crowned, making it an integral part of London’s colourful biography. -

The History of London

The History of London STUDENT A The Romans came to England in ____________ ( when? ) and built the town of Londinium on the River Thames. Londinium soon grew bigger and bigger. Ships came there from all over Europe and the Romans built _____________ ( what? ) from Londinium to other parts of Britain. By the year 400, there were 50,000 people in the city. Soon after 400 the Romans left, and we do not know much about London between 400 and 1000. In __________ (when? ) William the Conqueror came to England from Normandy in France. William became King of England and lived in ___________ ( where? ). But William was afraid of the people of London, so he built a big building for himself – the White Tower. Now it is part of the Tower of London and many ____________ ( who? ) visit it to see the Crown Jewels – the Queen’s gold and diamonds. London continued to grow. By 1600 there were ______________ ( how many? ) people in the city and by 1830 the population was one and a half million people. The railways came and there were ___________ ( what? ) all over the city. This was the London that Dickens New and wrote about – a city of very rich and very poor people. At the start of the 20th century, _____________ ( how many? ) people lived in London. Today the population of Greater London is seven and a half million. ______________ ( how many ?) tourists visit London every year and you can her 300 different languages on London’s streets! ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- STUDENT B The Romans came to England in AD43 and built the town of Londinium ____________ (where? ). -

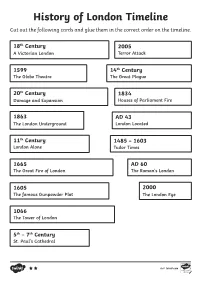

History of London Timeline Cut out the Following Cards and Glue Them in the Correct Order on the Timeline

History of London Timeline Cut out the following cards and glue them in the correct order on the timeline. 18th Century 2005 A Victorian London Terror Attack 1599 14th Century The Globe Theatre The Great Plague 20th Century 1834 Damage and Expansion Houses of Parliament Fire 1863 AD 43 The London Underground London Located 11th Century 1485 – 1603 London Alone Tudor Times 1665 AD 60 The Great Fire of London The Roman’s London 1605 2000 The famous Gunpowder Plot The London Eye 1066 The Tower of London 5th – 7th Century St. Paul’s Cathedral visit twinkl.com This famous theatre is where many Unfortunately, there was lots of damage to of William Shakespeare’s plays were London due to bombings during the Second performed. However, in 1613, it was World War including to St. Paul’s Cathedral. burnt down by a staged cannon fire in London once again expanded and many one of his plays. Today, a new 1990s big department stores such as Harrods and Globe Theatre, close to the original Selfridges were built. building, still holds performances of Shakespeare’s plays. 200 years after Guy Fawkes tried to Due to its trading links, Britain and London blow up the Houses of Parliament, became very powerful with goods from all over an accidental fire spread through the world being imported. the main building leaving only Westminster Hall undamaged. The th During the 18 century and Queen Victoria’s replacement was built ten years reign, the population of London expanded and later and still remains there today. many of the buildings we still see in London today were built during the Victorian times. -

London: Biography of a City

1 SYLLABUS LONDON: BIOGRAPHY OF A CITY Instructor: Dr Keith Surridge Contact Hrs: 45 Language of Instruction: English COURSE DESCRIPTION This course traces the growth and development of the city of London from its founding by the Romans to the end of the twentieth-century, and encompasses nearly 2000 years of history. Beginning with the city’s foundation by the Romans, the course will look at how London developed following the end of the Roman Empire, through its abandonment and revival under the Anglo-Saxons, its growing importance as a manufacturing and trading centre during the long medieval period; the changes wrought by the Reformation and fire during the reigns of the Tudors and Stuarts; the city’s massive growth during the eighteenth and nineteenth-centuries; and lastly, the effects of war, the loss of empire, and the post-war world during the twentieth-century. This course will outline the city’s expansion and its increasing significance in first England’s, and then Britain’s affairs. The themes of economic, social, cultural, political, military and religious life will be considered throughout. To complement the class lectures and discussions field trips will be made almost every week. COURSE OBJECTIVES By the end of the course students are expected to: • Know the main social and political aspects and chronology of London’s history. • Have developed an understanding of how London, its people and government have responded to both internal and external pressures. • Have demonstrated knowledge, analytical skills, and communication through essays, multiple-choice tests, an exam and a presentation. INSTRUCTIONAL METHODOLOGY The course will be taught through informal lectures/seminars during which students are invited to comment on, debate and discuss any aspects of the general lecture as I proceed.