Dust and Stone: Caucasian Sketches in Lermontov, Mandelstam and Grossman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

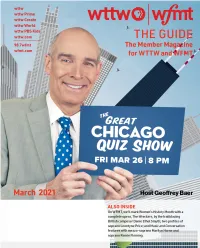

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Since its launch in 1982, the Marco Polo label has for over twenty years sought to draw attention to unexplored repertoire.␣ Its main goals have been to record the best music of unknown composers and the rarely heard works of well-known composers.␣ At the same time it originally aspired, like Marco Polo himself, to bring something of the East to the West and of the West to the East. For many years Marco Polo was the only label dedicated to recording rare repertoire.␣ Most of its releases were world première recordings of works by Romantic, Late Romantic and Early Twentieth Century composers, and of light classical music. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again, particularly those whose careers were affected by political events and composers who refused to follow contemporary fashions.␣ Of particular interest are the operas by Richard Wagner’s son Siegfried, who ran the Bayreuth Festival for so many years, yet wrote music more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck. To Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich, Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan), and Bruder Lustig, which further explores the mysterious medieval world of German legend is now added Der Heidenkönig (The Heathen King).␣ Other German operas included in the catalogue are works by Franz Schreker and Hans Pfitzner. Earlier Romantic opera is represented by Weber’s Peter Schmoll, and by Silvana, the latter notable in that the heroine of the title remains dumb throughout most of the action. -

Cello Concerto (1990)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers A-G RUSTAM ABDULLAYEV (b. 1947, UZBEKISTAN) Born in Khorezm. He studied composition at the Tashkent Conservatory with Rumil Vildanov and Boris Zeidman. He later became a professor of composition and orchestration of the State Conservatory of Uzbekistan as well as chairman of the Composers' Union of Uzbekistan. He has composed prolifically in most genres including opera, orchestral, chamber and vocal works. He has completed 4 additional Concertos for Piano (1991, 1993, 1994, 1995) as well as a Violin Concerto (2009). Piano Concerto No. 1 (1972) Adiba Sharipova (piano)/Z. Khaknazirov/Uzbekistan State Symphony Orchestra ( + Zakirov: Piano Concerto and Yanov-Yanovsky: Piano Concertino) MELODIYA S10 20999 001 (LP) (1984) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where his composition teacher was Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. Piano Concerto in E minor (1976) Alexander Tutunov (piano)/ Marlan Carlson/Corvallis-Oregon State University Symphony Orchestra ( + Piano Trio, Aria for Viola and Piano and 10 Romances) ALTARUS 9058 (2003) Aria for Violin and Chamber Orchestra (1973) Mikhail Shtein (violin)/Alexander Polyanko/Minsk Chamber Orchestra ( + Vagner: Clarinet Concerto and Alkhimovich: Concerto Grosso No. 2) MELODIYA S10 27829 003 (LP) (1988) MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Concertos A-G ISIDOR ACHRON (1891-1948) Piano Concerto No. -

The Concerts at Lewisohn Stadium, 1922-1964

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2009 Music for the (American) People: The Concerts at Lewisohn Stadium, 1922-1964 Jonathan Stern The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2239 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MUSIC FOR THE (AMERICAN) PEOPLE: THE CONCERTS AT LEWISOHN STADIUM, 1922-1964 by JONATHAN STERN VOLUME I A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2009 ©2009 JONATHAN STERN All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor Ora Frishberg Saloman Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor David Olan Date Executive Officer Professor Stephen Blum Professor John Graziano Professor Bruce Saylor Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract MUSIC FOR THE (AMERICAN) PEOPLE: THE LEWISOHN STADIUM CONCERTS, 1922-1964 by Jonathan Stern Adviser: Professor John Graziano Not long after construction began for an athletic field at City College of New York, school officials conceived the idea of that same field serving as an outdoor concert hall during the summer months. The result, Lewisohn Stadium, named after its principal benefactor, Adolph Lewisohn, and modeled much along the lines of an ancient Roman coliseum, became that and much more. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Since its launch in 1982, the Marco Polo label has for twenty years sought to draw attention to unexplored repertoire. Its main goals have been to record the best music of unknown composers and the rarely heard works of well-known composers. At the same time it aspired, like Marco Polo himself, to bring something of the East to the West and of the West to the East. For many years Marco Polo was the only label dedicated to recording rare repertoire. Most of its releases were world première recordings of works by Romantic, Late Romantic and Early Twentieth Century composers, and of light classical music. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again, particularly those whose careers were affected by political events and composers who refused to follow contemporary fashions. Of particular interest are the operas by Richard Wagner’s son Siegfried, who ran the Bayreuth Festival for so many years, yet wrote music more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck. To Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich, and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan), the new catalogue adds Bruder Lustig, which again explores the mysterious medieval world of German legend. Other German operas included in the catalogue are works by Franz Schreker and Hans Pfitzner. Earlier Romantic opera is represented by Weber’s Peter Schmoll, and by Silvana, the latter notable in that the heroine of the title remains dumb throughout most of the action. -

Temporary Assistant Professor in Slavic Studies – from Feb 2020 Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures, University of Verona

Curriculum Vitae Daniele Artoni PERSONAL INFORMATION Daniele Artoni RESEARCH Temporary assistant professor in Slavic Studies – from Feb 2020 Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures, University of Verona Postdoctoral research fellow in Slavic Studies – from Sep 2019 to Jan 2020 Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures, University of Verona • Research project: Accessible and inclusive teaching of Russian FL: An experimental study. Supervisor: Prof Manuel Boschiero Postdoctoral research fellow in Slavic Studies – from May 2018 to Apr 2019 Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures, University of Verona • Research project: Usage, identity and competence of the Russian as a Foreign Language in the Post-Soviet Southern Caucasus. Supervisor: Prof Stefano Aloe Postdoctoral research fellow in Slavic Studies – from Nov 2015 to Oct 2017 Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures, University of Verona • Research project: The construction of the Russian Orient in Carla Serena’s travel writings (1824-1884). Supervisor: Prof Stefano Aloe • Research conducted in the following centres: Civic Library in Verona, Library of Geography at the University of Padua, Archive of the Italian Geographical Society in Rome, National Library of France in Paris, National Parliamentary Library of Georgia in Tbilisi, Photoinstitut Bonartes in Vienna, National State Library in Moscow, Library of Foreign Literature in Moscow, National Archive of Georgia in Tbilisi, National Centre of Manuscripts Korneli Kekelidze in Tbilisi, National Library of Science -

Russian Connection Text Booklet

Three generations of composers, one Russian tradition The most substantial work on this CD, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Quintet in B flat, is entirely in the tradition of the Russia of the Tsars and the divertimento by Paul Juon was also written before the Revolution. The works by Ippolitov-Ivanov and Vasilenko were composed during the first decades of the Soviet Union. The establishment of the Soviet regime was a cultural turning point as well as a political one, so that the four works on this CD might seem to represent two entirely different worlds. But even though Ippolitov-Ivanov and Vasilenko were certainly influenced by cultural and political changes, the level of continuity is greater than one would expect. The main reason for this is to be found in the conservative idiom of these two composers. In addition, we are dealing with a strong tradition, one which was not easy to break with and which later turned out to be politically useful. On the present CD that tradition is represented by three generations of a “family” of composers. Rimsky- Korsakov taught Ippolitov-Ivanov, who in turn was the teacher of Vasilenko. Despite stylistic differences, Paul Juon can be considered a distant musical cousin of Vasilenko. Not only were they precisely the same age –both being born in March 1872– but they were contemporaries at the Moscow Conservatory. The compositions of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) can be divided into four different periods. Prior to 1873 he concentrated mainly on symphonies, but in about 1878 he commenced a series of impressive operas. -

Season 2011-2012

Season 2011-2012 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, June 22, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Stokowski Celebration at the Academy of Music Brahms Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 I. Un poco sostenuto—Allegro II. Andante sostenuto III. Un poco allegretto e grazioso IV. Adagio—Più andante—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio—Più allegro Intermission Ippolitov-Ivanov Caucasian Sketches, Suite No. 1, Op. 10 I. In a Mountain Pass II. In a Village III. In a Mosque IV. Procession of the Sardar Wagner Overture to Tannhäuser This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. Named one of “Tomorrow’s Conducting Icons” by Gramophone magazine, Yannick Nézet-Séguin has become one of today’s most sought-after conductors, widely praised for his musicianship, dedication, and charisma. A native of Montreal, he made his Philadelphia Orchestra debut in 2008 and in June 2010 was named the Orchestra’s next music director, beginning with the 2012-13 season. Artistic director and principal conductor of Montreal’s Orchestre Métropolitain since 2000, he became music director of the Rotterdam Philharmonic and principal guest conductor of the London Philharmonic in 2008. In addition to concerts with The Philadelphia Orchestra, Mr. Nézet-Séguin’s 2011-12 season included his Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, debut; a tour of Germany with the Rotterdam Philharmonic; appearances at the Metropolitan Opera, La Scala, and Netherlands Opera; and return visits to the Vienna and Berlin philharmonics and the Dresden Staatskapelle. Recent engagements have included the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Boston Symphony, and the Orchestre National de France; Vienna Philharmonic projects at the 2011 Salzburg, Montreux, and Lucerne festivals; and debut appearances at the Bavarian Radio Symphony and the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. -

THE NORTH CAUCASUS: T Minorities at a Crossroads • 94/5 the NORTH CAUCASUS : Minorities at a Crossroads an MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT

MINORITY RIGHTS GROUP INTERNATIONAL R E P O R THE NORTH CAUCASUS: T Minorities at a Crossroads • 94/5 THE NORTH CAUCASUS : Minorities at a Crossroads AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT G R M by HELEN KRAG and LARS FUNCH THE NORTH CAUCASUS: Minorities at a Crossroads by Helen Krag and Lars Funch © Minority Rights Group 1994 Acknowledgements British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Minority Rights Group gratefully acknowledges support A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library of the Danish Commission on Security and ISBN 1 897693 70 2 Disarmament, and all organizations and individuals who ISSN 0303 6252 gave financial and other assistance for this report. Published December 1994 Typeset by Brixton Graphics This report has been commissioned and is published by Printed in the UK on chlorine-free paper by Manchester Free Press Minority Rights Group as a contribution to public under- standing of the issue which forms its subject. The text and the views of the individual authors do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in all its aspects, the collective view of Minority Rights Group. THE AUTHORS DR HELEN KRAG is an associate professor and Head of Minority Studies at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, with a particular interest in minority-majority relations in Eastern Europe and the former USSR. Dr Krag is the Chair of MRG’s affiliate in Denmark, and a member of MRG’s Council and Programme Committee. She has written extensively on minority issues in the former USSR and Eastern Europe and acts as an advisor to various international bodies and human rights organi- zations. -

New York Flute Fair 2014

THE NEW YORK FLUTE CLUB: New York Flute Club FOR MORE INFORMATION Wendy Stern, President For more information about the New York Flute Club, please visit our Deirdre McArdle, Program Chair website, www.nyfluteclub.org, or contact one of the officers or presents coordinators listed below. For topics not listed, please email the webmaster at [email protected]. To contact us by postal mail, please write to the appropriate person at: T HE M AGIC F LUTES The New York Flute Club Park West Finance Station P.O. Box 20613 New York, NY 10025-1515 Archives Mailing Labels Nancy Toff, Archivist (Postal mailing lists only; [email protected] we do not rent our email list) Lucille Goeres, Membership Competition Secretary Patricia Wolf Zuber, Coordinator [email protected] [email protected] Membership, Dues, Change of with guest artists Concert information Address Wendy Stern, President Lucille Goeres, Membership THE FLUTISTS OF THE METROPOLITAN OPERA [email protected] Secretary Denis Bouriakov Concert & program proposals [email protected] Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson Wendy Stern, President Newsletter Maron Anis Khoury [email protected] Katherine Saenger, Editor Stephanie Mortimore Contributions & Other [email protected] Financial Matters Social media: Nneka Landrum, Treasurer Nicole Camacho, Coordinator nneka1973 @hotmail.com [email protected] Corporate Sponsors Website Fred Marcusa, Coordinator Joan Adam, Webmaster [email protected] [email protected] Sunday, March 16, 2014 Education & Enrichment Young Musicians Contest Stefani -

Education at Risk in the Northern Caucasus

EDUCATION AT RISK IN THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS: Adygheya, Dagestan, Ingushetiya, Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachai-Cherkessia, North Ossetia-Alania and Chechnya Dr. Irina Molodikova 2008 April ABOUT THE AUTHOR This report was prepared by Irina Molodikova, and funded by the Education Support Program of the Open Society Institute. Dr. Irina Molodikova is a research fellow at Central European University (Budapest) and Director of the Social Inequality and Exclusion seminar program for RESeT OSI (Budapest). She graduated from Moscow State University named after Lomonosov (Russia) and the University of Peace and Conflicts (Austria). Dr. Molodikova currently works as a researcher in the field of population migration and as a trainer in conflict resolution in multiethnic communities in the Northern Caucasus region and the Balkans. She is the author and editor of several books on migration problems and a visiting lecturer at Central European University and Moscow State University. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank the Association, Teachers of Chechnya, the non- governmental organization, Raduga, the teacher-psychologists from Ingushetiya, Dagestan, and North Ossetia-Alania, as well as the lecturers of the Stavropol State University, who helped to organize focus groups and conducted interviews with experts in the remote regions. Sincere gratitude to all others who volunteered their time to participate in the development of this report. LIST OF ACRONYMS ESP Education Support Program IDP Internally Displaced Person IOM International Organization