The Caucasus by Zaur Gasimov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obtaining World Heritage Status and the Impacts of Listing Aa, Bart J.M

University of Groningen Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing Aa, Bart J.M. van der IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Aa, B. J. M. V. D. (2005). Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 23-09-2021 Appendix 4 World heritage site nominations Listed site in May 2004 (year of rejection, year of listing, possible year of extension of the site) Rejected site and not listed until May 2004 (first year of rejection) Afghanistan Península Valdés (1999) Jam, -

Confirmed Soc Reports List 2015-2016

Confirmed State of Conservation Reports for natural and mixed World Heritage sites 2015 - 2016 Nr Region Country Site Natural or Additional information mixed site 1 LAC Argentina Iguazu National Park Natural 2 APA Australia Tasmanian Wilderness Mixed 3 EURNA Belarus / Poland Bialowieza Forest Natural 4 LAC Belize Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System Natural World Heritage in Danger 5 AFR Botswana Okavango Delta Natural 6 LAC Brazil Iguaçu National Park Natural 7 LAC Brazil Cerrado Protected Areas: Chapada dos Veadeiros and Natural Emas National Parks 8 EURNA Bulgaria Pirin National Park Natural 9 AFR Cameroon Dja Faunal Reserve Natural 10 EURNA Canada Gros Morne National Park Natural 11 AFR Central African Republic Manovo-Gounda St Floris National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 12 LAC Costa Rica / Panama Talamanca Range-La Amistad Reserves / La Amistad Natural National Park 13 AFR Côte d'Ivoire Comoé National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 14 AFR Côte d'Ivoire / Guinea Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve Natural World Heritage in Danger 15 AFR Democratic Republic of the Congo Garamba National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 16 AFR Democratic Republic of the Congo Kahuzi-Biega National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 17 AFR Democratic Republic of the Congo Okapi Wildlife Reserve Natural World Heritage in Danger 18 AFR Democratic Republic of the Congo Salonga National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 19 AFR Democratic Republic of the Congo Virunga National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 20 AFR Democratic -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Current Tourism Trends on the Black Sea Coast

CURRENT TOURISM TRENDS ON THE BLACK SEA COAST Minenkova Vera, Kuban State University, Russia Tatiana Volkova, Kuban State University, Russia Anatoly Filobok, Kuban State University, Russia Anna Mamonova, Kuban State University, Russia Sharmatava Asida, Kuban State University, Russia [email protected] The article deals with current trends of development of tourism on the Black Sea coast, related to geographical, economic, geopolitical factors. Key words: Black Sea coast, tourism and recreation complex, tourism, current trends. I. INTRODUCTION Black Sea coast has a number of natural features that define the high tourism and recreation potential of the territory. The unique combination of different resources defines the high tourism and recreation potential of the territory and creates conditions for the development of various forms of tourist activity. In view of the existing tourism industry (accommodation facilities, entertainment companies, etc.) and infrastructure we can talk about conditions for the development of almost all types of tourism: − cultural, educational and historical − health and resort − children − ecological − business − ethnographic − religious − agritourism (rural) − gastronomic and wine − active forms of tourism (diving, kitesurfing, hang-gliding, biking, caving, jeeping, rafting, horse riding, skiing and snowboarding, mountain climbing). II. TOURISM DEVELOPMENT FACTORS In general, current trends in the development of tourism on the Black Sea coast are determined by several factors: 1. The presence of significant historical and cultural potential and the unique culture of the local communities. According to archaeological evidence, the Caucasus is really to be considered one of the main points related to the "Cradle places of human civilization" (a series of sites of ancient human settlements in the Caucasus extends back over 300-350 thousand years). -

COLUMBIA UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL of ART HISTORY Winter 2021

COLUMBIA UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL of ART HISTORY Winter 2021 COLUMBIA UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL of ART HISTORY Winter 2021 The Columbia Undergraduate Journal of Art History January 2021 Volume 3, No. 1 A special thanks to Professor Barry Bergdoll and the Columbia Department of Art History and Archaeology for sponsoring this student publication. New York, New York Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Noah Percy Yasemin Aykan Designers Elizabeth Mullaney Lead Editors Zehra Naqvi Noah Seeman Lilly Cao Editor Kaya Alim Michael Coiro Jackie Chu Drey Carr Yuxin Chen Olivia Doyle Millie Felder Kaleigh McCormick Sophia Fung Sam Needleman Bri Schmidt Claire Wilson Special thanks to visual arts student and lead editor Lilly Cao, CC’22, for cover art, Skin I, 2020. Oil on canvas. An Editor’s Note Dear Reader, In a way, this journal has been a product of the year’s cri- ses—our irst independent Spring Edition was nearly interrupted by the start of the COVID-19 Pandemic and this Winter Edition arrives amidst the irst round of vaccine distribution. he humanities are often characterized as cloistered within the ivory tower, but it seems this year has irreversibly punctured that insulation (or its illusion). As under- graduates, our staf has been displaced, and among our ranks are the frontline workers and economically disadvantaged students who have borne the brunt of this crisis. In this issue, we have decided to confront the moment’s signiicance rather than aspire for escapist normalcy. After months of lockdown and social distancing in New York, we decided for the irst time to include a theme in our call for papers: Art in Conine- ment. -

Place of Myth in Traditional Society

Journal of Education; ISSN 2298-0245 Place of myth in traditional society Ketevan SIKHARULIDZE* Abstract The article deals with the place and function of mythology in traditional society. It is mentioned that mythology has defined the structure and lifestyle of society together with religion. The main universal themes are outlined based on which it became possible to classify myths, i.e. group them by the content. A description of these groups is provided and it is mentioned that a great role in the formation of mythological thinking was played by advancement of farming in agricultural activities. On its part, mythology played a significant role in the development of culture in general and in literature in particular. Key words: mythology, deities, traditional society, culture Mythology is one of the first fruits of human artistic think- The earth and chthonian creatures occupied the first place in his ing, however, it was not considered to be fiction in old times, world vision. So it should be thought that the earth, the mother but it was believed that the story in the myth had actually hap- of place and patron deity of the house were the first objects of pened. Mythology is a picture of the universe perceived by worship for the human being. Accordingly, the earth deities and a human being, which facilitated the development of poetic the mythological stories connected with them belonged to the thinking later. It is the product of collective poetic thinking and first religious systems. One of the main images of emanation we will never be able to identify its author. -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

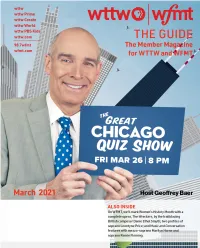

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

Anti-Marriage” in Ancient Georgian Society

“Anti-marriage” in ancient Georgian society. KEVIN TUITE, UNIVERSITÉ DE MONTRÉAL ABSTRACT One of the more striking features of the traditional cultures of the northeastern Georgian provinces of Pshavi and Xevsureti, is the premarital relationship known as c’ac’loba (Pshavi) or sc’orproba (Xevsureti). This relationship was formed between young women and men from the same community, including close relatives. It had a strong emotional, even intimate, component, yet it was not to result in either marriage or the birth of a child. Either outcome would have been considered incestuous. In this paper I will demonstrate that the Svans, who speak a Kartvelian language distantly related to Georgian, preserve a structurally-comparable ritual the designation of which — ch’æch’-il-ær — is formed from a root cognate with that of c’ac’-l-oba. On the basis of a comparative analysis of the Svan and Pshav-Xevsurian practices in the context of traditional Georgian beliefs concerning marriage and relationships between “in-groups” and “out-groups”, I will propose a reconstruction of the significance of *c´’ac´’-al- “anti-marriage” in prehistoric Kartvelian social thought. 0. INTRODUCTION. For over a century, specialists in the study of Indo-European linguistics and history have examined the vocabulary of kinship and alliance of the IE languages for evidence of the familial and social organization of the ancestral speech community (e.g., Benveniste 1969; Friedrich 1966; Bremmer 1976; Szemerényi 1977). The three indigenous language families of the Caucasus have received far less attention in this regard; comparatively few studies have been made of the kinship vocabularies of the Northwest, Northeast or South Caucasian families, save for the inclusion of such terms in etymological dictionaries or inventories of basic lexical items (Shagirov 1977; Klimov 1964; Fähnrich and Sardshweladse 1995; Xajdakov 1973; Kibrik and Kodzasov 1990). -

Review for Igitur (Italy) — Mai 13, 2003 — Pg 1 Review of Mify Narodov Mira (“Myths of the Peoples of the World”), Chief Editor S

Review for Igitur (Italy) — mai 13, 2003 — pg 1 Review of Mify narodov mira (“Myths of the peoples of the world”), chief editor S. A. Tokarev. Moscow: Sovetskaia Entsiklopediia, 1987. Two volumes, 1350 pp. Reviewed by Kevin Tuite, Dépt. d’anthropologie, Univ. de Montréal. 1. Introductory remarks. The encyclopedia under review (henceforth abbreviated MNM) is an alphabetically-arranged two-volume reference work on mythology, compiled by a team of Soviet scholars. Among the eighty or so contributors, two individuals, the celebrated Russian philologists Viacheslav V. Ivanov and Vladimir N. Toporov, wrote most of the longer entries, as well as the shorter articles on Ket, Hittite, Baltic, Slavic and Vedic Hindu mythologies. Other major contributors include Veronika K. Afanas’eva (Sumerian and Akkadian), L. Kh. Akaba and Sh. Kh. Salakaia (Abkhazian), S. B. Arutiunian (Armenian), Sergei S. Averintsev (Judaism and Christianity), Vladimir N. Basilov (Turkic), Mark N. Botvinnik, V. Iarkho and A. A. Takho-Godi (Greek), Mikheil Chikovani and G. A. Ochiauri (Georgian), V. A. Kaloev (Ossetic), Elena S. Kotliar (African), Leonid A. Lelekov (Iranian), A. G. Lundin and Il’ia Sh. Shifman (Semitic), Eleazar M. Meletinskii (Scandinavian, Paleo-Siberian), L. E. Miall (Buddhism), M. I. Mizhaev (Circassian), Mikhail B. Piotrovskii (Islam), Revekka I. Rubinshtein (Egyptian), Elena M. Shtaerman (Roman). Most of the thousands of entries are sketches of deities and other mythological characters, including some relatively obscure ones, from a number of classical and modern traditions. Coverage is especially extensive for the classical Old World and the indigenous populations of the former USSR, but Africa, Asia and the Americas are well represented. -

In Armenia ------5

TOPICAL DIALOGUES N 8 2019 The present electronic bulletin “Topical Dialogues – 2019” was issued with the support of Black Sea Trust for Regional Cooperation (a project by the G. Marshall Fund). Opinions expressed in this bulletin do not necessarily represent those of the Black Sea Trust or its partners. 2 Content ONE TOPIC - TWO AUTHORS SUZANNA BARSEGHYAN (Armenia) The perceptions of the “enemy’s image” in Armenia -------------------------------5 ARIF YUNUSOV (Azerbaijan) Stereotypes and the “image of the enemy” in Azerbaijan--------------------------13 Arif Yunusov’s comment on Suzanna Barseghyan’s article ----------------------25 Suzanna Barseghyan’s comment on Arif Yunusov’s article ----------------------28 3 One topic covered by two authors In this issue of the bulletin we bring to you an Armenian and Azerbaijani authors' views of the origin and functions of the image of the enemy in their respective societies. And in the “Comments to the Articles” section , the Armenian and Azerbaijani authors commented on each other’s articles. Judging by the content of these comments, the discussion at distance could still be continued by a whole series of new comments. But both the articles and these first comments reflect both the attitude to the opposite side in each country, and the perception of this attitude at the moment. The materials were prepared within the framework of the “Public Dialogues for Communication between Armenian and Azerbaijani Specialists” project, implemented by the “Region” Research Center. The project is supported by the Black Sea Trust for Regional Cooperation (BST). The project partner is the Institute for Peace and Democracy (the Netherlands). The "Public Dialogues" website (www.publicdialogues.info) was created in 2012 by the “Region” Research Center and the Institute for Peace and Democracy which operated in Azerbaijan at the time. -

The Election Process of the Regional Representatives to the Parliament of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan

№ 20 ♦ УДК 342 DOI https://doi.org/10.32782/2663-6170/2020.20.7 THE ELECTION PROCESS OF THE REGIONAL REPRESENTATIVES TO THE PARLIAMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN ВИБОРЧИЙ ПРОЦЕС РЕГІОНАЛЬНИХ ПРЕДСТАВНИКІВ У ПАРЛАМЕНТ АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНСЬКОЇ ДЕМОКРАТИЧНОЇ РЕСПУБЛІКИ Malikli Nurlana, PhD Student of the Lankaran State University The mine goal of this article is to investigate the history of the creation of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan par- liament, laws on parliamentary elections, and the regional election process in parliament. In addition, an analysis of the law on elections to the Azerbaijan Assembly of Enterprises. The article covers the periods of 1918–1920. The presented article analyzes historical processes, carefully studied and studied the process of elections of regional representatives to the Parliament of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan. Realities are reflected in an objective approach. A comparative historical study of the election of regional representatives was carried out in the context of the creation of the parliament of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan and the holding of parliamentary elections. The scientific novelty of the article is to summarize the actions of the parliament of the first democratic republic of the Muslim East. Here, attention is drawn to the fact that before the formation of the parliament, the National Assembly, in which the highest executive power, trans- ferred its powers to the legislative body and announced the termination of its activities. It is noted that the Declaration of Independence of Azerbaijan made the Republic of Azerbaijan a democratic state. It is from this point of view that attention is drawn to the fact that the government of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic had to complete the formation of institutions capable of creating a solid legislative base in a short time.