Bodies and Space in Pinter and Kane CHAN, Woon Ki a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced info the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on untii complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Sarah Kane's Post-Christian Spirituality in Cleansed

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Winter 2020 Sarah Kane's Post-Christian Spirituality in Cleansed Elba Sanchez Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Performance Studies Commons, Playwriting Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Sanchez, Elba, "Sarah Kane's Post-Christian Spirituality in Cleansed" (2020). All Master's Theses. 1347. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1347 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SARAH KANE’S POST-CHRISTIAN SPIRITUALITY IN CLEANSED __________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University __________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Theatre Studies __________________________________________ by Elba Marie Sanchez Baez March 2020 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Elba Marie Sanchez Baez Candidate for the degree of Master of Arts APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY _____________ __________________________________________ Dr. Emily Rollie, Committee Chair _____________ _________________________________________ Christina Barrigan M.F.A _____________ _________________________________________ Dr. Lily Vuong _____________ _________________________________________ Dean of Graduate Studies ii ABSTRACT SARAH KANE’S POST-CHRISTIAN SPIRITUALITY IN CLEANSED by Elba Marie Sanchez Baez March 2020 The existing scholarship on the work of British playwright Sarah Kane mostly focuses on exploring the use of extreme acts of violence in her plays. -

In Whose Face?! (Angry Young) Theatre Makers and the Targets of Their Provocation

In whose face?! (Angry young) theatre makers and the targets of their provocation Spencer Hazel Hazel, Spencer (2015) In whose face?! (Angry young) theatre makers and the targets of their provocation. In Susan Blattes and Samuel Cuisinier-Delorme (Eds.) Special Issue «Le théâtre In-Yer-Face aujourd’hui: bilans et perspectives», Coup de Theatre, 29, 45-68 1. Introduction The current article offers a response to Aleks Sierz’ (Sierz, 2007) account of how he produced a particular narrative that revolved around a bounded network of theatre practitioners operating in Britain in the latter half of the 1990s, whose work he subsequently labeled as constituting “In-Yer-Face-Theatre” (Sierz 2001). I will be arguing that in order to evaluate any lasting impact that the particular selection of theatre artists have had on current theatre, a modified narrative may serve as a more relevant map through which to chart the developments in UK theatre during what have been termed the “nasty nineties”, and beyond. The alternative narrative that I am proposing may initially seem to offer these players lesser roles in what makes up the grand design of the end-of-the-century British cultural scene, diminishing them from the prime billing that they have enjoyed to date in the work of Sierz and others who have adopted the framework. That is not, however, what I set out to do here. Rather, this new narrative re-incorporates these playwrights into a larger interdisciplinary endeavour that characterized the times in which they happened to be working, an In-Yer-Face decade which was witness to a broader reconceptualization of the possibilities of cultural engagement across a range of forms of expression, both in the performing arts such as theatre, and in other artistic strands like visual art, television and music. -

A Tanatopoética De Sarah Kane: Escritos Para a Morte

0 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS, LETRAS E ARTES PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM RUMMENIGGE MEDEIROS DE ARAÚJO A Tanatopoética de Sarah Kane: escritos para a morte Natal/RN 2016 1 RUMMENIGGE MEDEIROS DE ARAÚJO A Tanatopoética de Sarah Kane: escritos para a morte Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Estudos da Linguagem da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Linha de Pesquisa: Poéticas da Modernidade e da Pós-Modernidade como requisito parcial para a obtenção do grau de Doutor em Literatura Comparada. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Alex Beigui de Paiva Cavalcante Natal/RN 2016 2 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte - UFRN Sistema de Bibliotecas - SISBI Catalogação de Publicação na Fonte. UFRN - Biblioteca Setorial do Centro de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes - CCHLA Araujo, Rummenigge Medeiros de. A tanatopoética de Sarah Kane: escritos para a morte / Rummenigge Medeiros de Araujo. - 2016. 298f.: il. Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes. Programa de Pós- graduação em Estudos da Linguagem. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Alex Beigui de Paiva Cavalcante. 1. Literatura inglesa. 2. Kane, Sarah, 1971-1999. 3. Tanatopoética. 4. Escrita performática. I. Cavalcante, Alex Beigui de Paiva. II. Título. RN/UF/BS-CCHLA CDU 821.111-1 3 RUMMENIGGE MEDEIROS DE ARAÚJO A Tanatopoética de Sarah Kane: escritos para a morte Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos da Linguagem, no Centro de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do grau de Doutor (a) em Literatura Comparada. -

Sarah Kane's Concern for Humanity: Blasted As an Antiwar Play

DOI: 10.7763/IPEDR. 2012. V51. 20 Sarah Kane’s Concern for Humanity: Blasted as an Antiwar Play + Ayoub Dabiri Islamic Azad University, Abhar Branch Abstract. Although Sarah Kane’s debut play, Blasted, was castigated by so many critics because of its onstage performance of violence, it can be reconsidered as an antiwar play which shows its author’s concern for humanity and her hope for a better world where wars must be avoided. This paper discusses Blasted as an antiwar play which addresses the audience’s indifference toward war as a threat for humanity. Keywords: Sara Kane, Antiwar Drama, Violence. 1. Introduction 1.1. Sarah Kane and Her Oeuvre Sarah Kane, the renowned British playwright, was born in 1971 in Essex. She graduated in Drama with first class honours from Bristol University and then did an M.A in Creative Writing at Birmingham University. Kane suffered from depression and had spells in hospital. After an unsuccessful suicide attempt with sleeping pills, she finally hung herself in the hospital where she was under treatment. Limited to years 1995 to 1999, Kane’s oeuvre comprises five plays and a short television script. After the performance of her debut play, Blasted, in 1995 she wrote Phaedra’s Love in 1996. While Phaedra’s Love contained violent content and language, it did not cause much controversy over its representation of violence and the reception of the play was not as hostile and intense as the reception of her debut play. In 1998 Kane wrote Cleansed, a play with themes of imprisonment, punishment, torture and love. -

Being in Auschwitz: a Study of Sarah Kane's Cleansed As a Vivid Picture

Being in Auschwitz: A Study of Sarah Kane’s Cleansed as a Vivid Picture of Nazi Human Experimentation Sara Setayesh Dr. Alireza Anushiravani Department of Foreign Languages and Linguistics Department of Foreign Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Literature and Humanities Faculty of Literature and Humanities University of Shiraz University of Shiraz Shiraz, IRAN Shiraz, IRAN Introduction: Sarah Kane and Her Oeuvre One of the most influential voices in modern European theatre, Sarah Kane, wrote five plays before her “suicide in 1999, just three days after the completion of her final play, 4:48 Psychosis, [which] virtually guaranteed the visionary playwright a place in theatrical history among the likes of George Buchner, Heinrich von Kleist, and Virginia Woolf” (Earnest 153). Although Kane attracted controversy while alive now “many critics celebrate Kane’s contribution: each of her plays is an experiment in new theatrical form, challenging traditional naturalistic writing” (Hurley 1143). Her first play, Blasted, was produced at the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs in 1995. Her second and third play, Phaedra’s Love and Cleansed were produced at the Gate Theatre in 1996 and at the Royal Court Theatre Downstairs in 1998 respectively and in September 1998, Crave was produced by Paines Plough and Bright Ltd at the Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh. 4.48 Psychosis, Kane’s last play, premiered at the Royal Court Jerwood Theatre Upstairs in June 2000 and her short film, Skin, produced by British Screen, premiered in June 1997. Kane committed suicide in 1999 at the age of 28. Her drama breaks away from the conventions of naturalist theatre using extreme stage action to depict themes of love, death and physical and psychological pain and torture. -

“4.48 Psychosis” As a Suicide Note of Sarah Kane? IVO ČERMÁK, VLADIMÍR CHRZ, KATEŘINA ZÁBRODSKÁ

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Huddersfield Repository 12 “4.48 Psychosis” as a Suicide Note of Sarah Kane? IVO ČERMÁK, VLADIMÍR CHRZ, KATEŘINA ZÁBRODSKÁ Introduction Sarah Kane, the author of several so-called ‘cool’ dramas, committed suicide. She was 28 years old. It is always a tragedy when a young person dies in this way, but we can say that artists often react more sensitively, and sometimes much too sensitively, to the harsh world that surrounds them, a world which is the inspiration for their work, and which sometimes overwhelms them.1 In our paper we strived to respond to the question, what might have hastened the suicidal process of Sarah Kane. We focused on her last play, “4.48 Psychosis,” which seems to provide the key answer to the question included in the title.2 I (Ivo) had previously interpreted Psychosis 4.48 in a paper published in Czech, and later I asked Vladimír and Kateřina (Kate) to interpret the play as well. Thus we have three perspectives, from which we can develop an understanding of the suicide of Sarah Kane. The space for interpretation is limited in this paper so we elaborated two perspectives – “regressive” and “genre” ones – more thoroughly. Kate’s poststructuralistic view is not presented here in detail, but there are many similarities between her interpretation and those presented in this paper. The Life Story of Sarah Kane Her autobiographical details have so far not been made available by her relatives for understandable reasons. The biographical notes of friends and colleagues and the interviews, which she gave to the media, are much too fragmentary and cannot provide a reliable source for reconstructing the relationship between the events of Sarah’s life and her suicide. -

Witnesses Inside/Outside the Stage. the Purpose of Representing Violence in Edward Bond's Saved (1965) and Sarah Kane's Blas

Witnesses Inside/Outside the Stage. The Purpose Of Representing Violence In Edward Bond’s Saved (1965) And Sarah Kane’s Blasted (1995) Testigos Dentro/Fuera Del Escenario. El Objetivo De La Representación De La Violencia En Saved (1965) De Edward Bond Y Blasted (1995) De Sarah Kane Laura López Peña1 Abstract In spite of the thirty years span of time between the two productions, Edward Bond’s Saved and Sarah Kane’s Blasted provoked a similar outburst of reactions when they first opened at the Royal Court Theatre in 1965 and 1995, respectively. Depicting various types of violence onstage, the two plays aim at making spectators connect different forms of cruelty so that they can be moved to react against them in real life. In order to do so, both plays highlight the question of witnessing at two levels: on the one hand, at the level of character, the plays portray individuals who witness, suffer and/or inflict brutality, becoming, thus, participants in the ongoing cycles of violence onstage; whereas, on the other hand, at the level of audience, spectators too become direct –and silent– witnesses to the plays and their depicted cruelties, at the same time that they are called to react against the horrors they have experienced in the theatrical fictional world. The aim of this paper is, therefore, to analyze how Saved and Blasted engage in arising spectators’ awareness of their own passivity in front of several forms of violence, and invite their audience to actively denounce not only wars and conflicts taking place in distant places but also in their own immediate surroundings. -

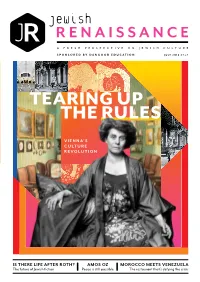

Tearing up the Rules

Jewish RENAISSANCE A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON JEWISH CULTURE SPONSORED BY DANGOOR EDUCATION JULY 2018 £7.25 TEARING UP THE RULES VIENNA’S CULTURE REVOLUTION IS THERE LIFE AFTER ROTH? AMOS OZ MOROCCO MEETS VENEZUELA The future of Jewish fiction Peace is still possible The restaurant that’s defying the crisis JR Pass on your love of Jewish culture for future generations Make a legacy to Jewish Renaissance ADD A LEGACY TO JR TO YOUR WILL WITH THIS SIMPLE FORM WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/CODICIL GO TO: WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/DONATIONS FOR INFORMATION ON ALL WAYS TO SUPPORT JR CHARITY NUMBER 1152871 JULY 2018 CONTENTS WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK JR YOUR SAY… Reader’s rants, raves 4 and views on the April issue of JR. WHAT’S NEW We announce the 6 winner of JR’s new arts award; Mike Witcombe asks: is there life after Roth? FEATURE Amos Oz on Israel at 10 70, the future of peace, and Trump’s controversial embassy move. FEATURE An art installation in 12 French Alsace is breathing new life into an old synagogue. NATALIA BRAND NATALIA © PASSPORT Vienna: The writers, 14 artists, musicians and thinkers who shaped modernism. Plus: we speak to the contemporary arts activists working in Vienna today. MUSIC Composer Na’ama Zisser tells Danielle Goldstein about her 30 CONTENTS opera, Mamzer Bastard. ART A new show explores the 1938 32 exhibition that brought the art the Nazis had banned to London. FILM Masha Shpolberg meets 14 34 the director of a 1968 film, which followed a group of Polish exiles as they found haven on a boat in Copenhagen. -

British Communism and the Politics of Literature, 1928-1939

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses British Communism and the politics of literature, 1928-1939. Bounds, Philip How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Bounds, Philip (2003) British Communism and the politics of literature, 1928-1939.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42543 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ BRITISH COMMUNISM AND THE POLITICS OF LITERATURE, 1928-1939 PHILIP BOUNDS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF WALES IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF WALES SWANSEA 2003 ProQuest Number: 10805292 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

EXISTENTIALIST VIEW of the SELF in SARAH KANE's PLAYS Tuğba AYGAN English Language and Literature Department Master Thesis A

EXISTENTIALIST VIEW OF THE SELF IN SARAH KANE’S PLAYS Tuğba AYGAN English Language And Literature Department Master Thesis Assist. Prof. Yeliz BĠBER 2012 All rights reserved T.C. ATATURK UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT Tuğba AYGAN EXISTENTIALIST VIEW OF THE SELF IN SARAH KANE’S PLAYS MASTER THESIS SUPERVISOR Assist. Prof. Yeliz BĠBER ERZURUM-2012 I TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................... III ÖZET ..............................................................................................................................IV ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... V INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE EXISTENTIALIST SELF 1.1. EXISTENTIALIST SELF ....................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. Sartrean Existentialism and the Existential Self ......................................... 10 1.1.2. The Existential Concept of Individual Freedom.......................................... 16 1.1.3. Authenticity and Inauthenticity (Bad Faith): Existence Modes of the Self .................................................................................................................................... 22 1.1.4. Self as Social Being ........................................................................................ -

Redalyc.Witnesses Inside/Outside the Stage. the Purpose of Representing Violence in Edward Bond's Saved (1965) and Sarah Kane

Revista Folios ISSN: 0123-4870 [email protected] Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Colombia López Peña, Laura Witnesses Inside/Outside the Stage. The Purpose Of Representing Violence In Edward Bond’s Saved (1965) And Sarah Kane’s Blasted (1995) Revista Folios, núm. 29, enero-junio, 2009, pp. 111-118 Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=345941359009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Witnesses Inside/Outside the Stage. The Purpose Of Representing Violence In Edward Bond’s Saved (1965) And Sarah Kane’s Blasted (1995) Testigos Dentro/Fuera Del Escenario. El Objetivo De La Representación De La Violencia En Saved (1965) De Edward Bond Y Blasted (1995) De Sarah Kane Laura López Peña1 Abstract In spite of the thirty years span of time between the two productions, Edward Bond’s Saved and Sarah Kane’s Blasted provoked a similar outburst of reactions when they first opened at the Royal Court Theatre in 1965 and 1995, respectively. Depicting various types of violence onstage, the two plays aim at making spectators connect different forms of cruelty so that they can be moved to react against them in real life. In order to do so, both plays highlight the question of witnessing at two levels: on the one hand, at the level of character, the plays portray individuals who witness, suffer and/or inflict brutality, becoming, thus, participants in the ongoing cycles of violence onstage; whereas, on the other hand, at the level of audience, spectators too become direct –and silent– witnesses to the plays and their depicted cruelties, at the same time that they are called to react against the horrors they have experienced in the theatrical fictional world.