Public Transport System in the Capital of Kyrgyzstan: Current Situation and Analysis of Its Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenth Regional Environmentally Sustainable Transport (EST) Forum in Asia

ISSUED WITHOUT FORMAL EDITING Chair’s Summary Tenth Regional Environmentally Sustainable Transport (EST) Forum in Asia 2030 Road Map for Sustainable Transport ~ Aligning with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 14-16 March 2017 Venue: Don Chan Palace Hotel & Convention, Vientiane, Lao PDR Forum Chair H.E. Dr. Bounchanh Sinthavong, Minister of the Public Works and Transport, Lao People's Democratic Republic I. Introduction 1. The Intergovernmental Tenth Regional Environmentally Sustainable Transport (EST) Forum in Asia co- organized by the Ministry of Public Works and Transport (MPWT) of the Government of Lao PDR, the Ministry of the Environment of the Government of Japan (MOE-Japan), the Partnership on Sustainable, Low Carbon Transport (SLoCaT), the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP), the United Nations Office for Sustainable Development (UNOSD) and the United Nations Centre for Regional Development (UNCRD), from 14 to 16 March 2017 in Vientiane, Lao PDR, with the theme of “2030 Road Map for Sustainable Transport ~ Aligning with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)”. 2. The Forum was officially inaugurated by H.E Mr. Somdy Douangdy, Deputy Prime Minister of the Lao PDR, and chaired by H.E. Dr. Bounchanh Sinthavong, Minister of Public Works and Transport, Lao PDR. The Forum was attended by over three hundred participants comprised of national and city government representatives from thirty-eight countries (Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, People's Republic of China (hereinafter, -

Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’S Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests

JUNE 2015 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 202-887-0200 | www.csis.org Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 4501 Forbes Boulevard Lanham, MD 20706 301- 459- 3366 | www.rowman.com Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’s Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests AUTHORS Andrew C. Kuchins Jeffrey Mankoff Oliver Backes A Report of the CSIS Russia and Eurasia Program ISBN 978-1-4422-4100-8 Ë|xHSLEOCy241008z v*:+:!:+:! Cover photo: Labusova Olga, Shutterstock.com. Blank Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’s Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests AUTHORS Andrew C. Kuchins Jeffrey Mankoff Oliver Backes A Report of the CSIS Rus sia and Eurasia Program June 2015 Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 594-61689_ch00_3P.indd 1 5/7/15 10:33 AM hn hk io il sy SY eh ek About CSIS hn hk io il sy SY eh ek For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to hn hk io il sy SY eh ek develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are hn hk io il sy SY eh ek providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart hn hk io il sy SY eh ek a course toward a better world. hn hk io il sy SY eh ek CSIS is a nonprofit or ga ni za tion headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full- time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analy sis and hn hk io il sy SY eh ek develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. -

Whole-Body Vibration in Bus Drivers: Association with Physical Fitness and Low Back Pain

International Journal for Innovation Education and Research ISSN 2411-2933 01 February 2021 Whole-Body Vibration in Bus Drivers: Association with Physical Fitness and Low Back Pain Bruno Sergio Portela (Corresponding author) Department of Physical Education, Midwest State University of Paraná, (UNICENTRO). E-mail: [email protected] Paulo Henrique Trombetta Zannin Laboratory of Environmental and Industrial Acoustics and Acoustic Comfort, Federal University of Paraná, (UFPR). Abstract The aim of the study was to investigate the relationship between exposure to whole body vibration, prevalence of low back pain and level of physical fitness in bus drivers. The measurement of whole body vibration was in 100 city buses with different characteristics and the prevalence of low back pain was assessed in 200 drivers with a measurement of physical fitness level. Descriptive statistics with mean and standard deviation and inferential statistics were used with the Kurskal-Wallis test, Dunn's multiple comparisons test, Poisson regression and significance level of p <0.05. The results demonstrate significant differences between the vehicle models, characterizing the conventional and articulated buses on the y and z axes with higher levels of vibration. Drivers working with conventional and articulated vehicles had a higher prevalence of low back pain with 57.5 and 60%, respectively. The level of physical fitness was low in most of the sample, however, the drivers of bi-articulated and micro bus had higher levels. Poisson regression with the outcome of low back pain, showed the factors that showed a significant prediction: age, working time, abdominal muscle resistance, lumbar strength, RMSy and RMSz. Keywords: Whole body vibration, bus drivers, low back pain and physical fitness 1. -

Getting Around Effective and Modern Transport Options

GETTING AROUND EFFECTIVE AND MODERN TRANSPORT OPTIONS BY TAXI OR COACH CAR RENTAL Luxury air-conditioned coaches and shuttle buses will move Cape Town offers a wide selection of car rental companies with delegates between the airport, hotels, the CTICC and their good road systems. An international driver’s license is required functions. Metered taxis are also available. and driving will be on the left hand side of the road. MYCITI BUS SERVICE BY TRAIN The MyCiti airport-to-city service runs between the Cape Town Cape Town station is situated within walking distance of the International Airport and the Civic Centre bus stations via the N2 Westin Grand South Africa Arabella Quays Hotel, and the and Nelson Mandela Boulevard. This service will operate between functional Metro Rail system connects the city centre with the 20 and 24 hours a day at a cost of R57,00 one way. It will depart northern suburbs, southern suburbs and Cape Flats. every six to 30 minutes, depending on demand. The MyCiti inner- city bus service provides convenient transport to hotels, TOPLESS TOURS accommodation nodes, restaurants, entertainment areas, parking This service visits the major attractions around the city and is a areas, and places of interest. Each journey costs R10,00 and buses convenient way to experience Cape Town’s many varied depart every 10 to 30 minutes and operate between 20 and 24 attractions. The bright red “Hop-on Hop-off” city sightseeing hours a day. service comes complete with nine multilingual commentary channels, plus a “kiddie’s” channel and is an ideal and convenient BY BUS method of travelling to and viewing the most popular attractions The new Integrated Rapid Transit (IRT) System offers international in and around Cape Town. -

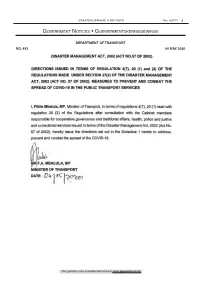

Disaster Management Act: Directions: Measures to Address, Prevent And

STAATSKOERANT, 4 MEI 2020 No. 43272 3 GOVERNMENT NOTICES • GOEWERMENTSKENNISGEWINGS Transport, Department of/ Vervoer, Departement van DEPARTMENTDEPARTMENT OF OF TRANSPORT TRANSPORT NO. 493 04 MAY 2020 493 Disaster Management Act (57/2002): Directions issued in terms of Regulation 4 (7), 20 (1) and (2) of the Regulations made under Section 27 (2) of the Act: Measures to Prevent and Combat the Spread of COVID-19 in the Public Transport Services 43272 DISASTER MANAGEMENT ACT, 2002 (ACT NO,57 OF 2002) DIRECTIONS ISSUED IN TERMS OF REGULATION 4(7), 20 (1) and (2) OF THE REGULATIONS MADE UNDER SECTION 27(2) OF THE DISASTER MANAGEMENT ACT, 2002 (ACT NO. 57 OF 2002): MEASURES TO PREVENT AND COMBAT THE SPREAD OF COVID -19 IN THE PUBLIC TRANSPORT SERVICES I, Mlle Mbalula, MP, Minister of Transport, in terms of regulations 4(7), 20 (1) read with regulation 20 (2) of the Regulations after consultation with the Cabinet members responsible for cooperative governance and traditional affairs, health, police and justice and correctional services issued in terms of the Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act No. 57 of 2002), hereby issue the directions set out in the Schedule 1 hereto to address, prevent and combat the spread of the COVID -19. F.A. MBALULA, MP MINISTER OF TRANSPORT DATE: O (. 01-`20,-a,--) This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 4 No. 43272 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 4 MAY 2020 SCHEDULE 1. DEFINITIONS In these directions, any word or expression bears the meaning assigned to it in the National Land Transport Act, 2009 or -

Truck 45.0.0

IDC5 software update TRUCK 45.0.0 TEXA S.p.A. Via 1 Maggio, 9 31050 Monastier di Treviso Treviso - ITALY Tel. +39 0422 791311 Fax +39 0422 791300 www.texa.com - [email protected] IDC5 TRUCK software update 45.0.0 The new diagnostic features included in the all mechanics the opportunity to use diagnostic IDC5 TRUCK update 45 allow working on a large tools that are always updated and state-of-the- number of vehicles that belong to makes of the art, to operate successfully on the vast majority most popular manufacturers. The work TEXA’s of vehicles on the road. developers carried out on industrial vehicles, The TRUCK update 45 also offers new, very useful light commercial vehicles and buses guarantees Wiring Diagrams and DASHBOARDs. WORLDWIDE MARKET CHEVROLET / ISUZU: • Instrumentation. • The new model D-MAX [02>] 2.5 TD was • The new model Berlingo M59 engine1.6i 16V developed with the following systems: Flex Kat was developed with the • ABS; following systems: • Airbag; • ABS; • Body computer; • Airbag; • Immobiliser; • Anti-theft system; • Diesel injection; • Radio; • Transfer case; • Body computer; • Service warning light. • Door locking; • Multi-function display; CITROËN: • Immobiliser; • The new model Berlingo [14>] (B9e) EV was • Flex Fuel injection; developed with the following systems: • CD multiplayer; • ABS; • Auxiliary heating; • Anti-theft system; • Instrumentation. • Airbag; • Body computer; COBUS: • A/C system; • The new model Series 2000 & 3000 Euro 3 - • Comfort system; EM3 was developed with the following systems: • Emergency call; • Automatic transmission; • Multi-function display; • Diesel injection; • Steering column switch unit; • Network system; • Trailer control unit; • Motor vehicle control; • Hands-free system; • Instrumentation; • CD multiplayer; • Tachograph. -

Ivecobus Range Handbook.Pdf

CREALIS URBANWAY CROSSWAY EVADYS 02 A FULL RANGE OF VEHICLES FOR ALL THE NEEDS OF A MOVING WORLD A whole new world of innovation, performance and safety. Where technological excellence always travels with a true care for people and the environment. In two words, IVECO BUS. CONTENTS OUR HISTORY 4 OUR VALUES 8 SUSTAINABILITY 10 TECHNOLOGY 11 MAGELYS DAILY TOTAL COST OF OWNERSHIP 12 HIGH VALUE 13 PLANTS 14 CREALIS 16 URBANWAY 20 CROSSWAY 28 EVADYS 44 MAGELYS 50 DAILY 56 IVECO BUS CHASSIS 68 IVECO BUS ALWAYS BY YOUR SIDE 70 03 OUR HISTORY ISOBLOC. Presented in 1938 at Salon de Paris, it was the fi rst modern European coach, featuring a self-supporting structure and rear engine. Pictured below the 1947 model. 04 PEOPLE AND VEHICLES THAT TRANSPORTED THE WORLD INTO A NEW ERA GIOVANNI AGNELLI JOSEPH BESSET CONRAD DIETRICH MAGIRUS JOSEF SODOMKA 1866 - 1945 1890 - 1959 1824 - 1895 1865 - 1939 Founder, Fiat Founder, Société Anonyme Founder, Magirus Kommanditist Founder, Sodomka des établissements Besset then Magirus Deutz then Karosa Isobloc, Chausson, Berliet, Saviem, Fiat Veicoli Industriali and Magirus Deutz trademarks and logos are the property of their respective owners. 05 OVER A CENTURY OF EXPERIENCE AND EXPERTISE IVECO BUS is deeply rooted into the history of public transport vehicles, dating back to when the traction motor replaced horse-drawn power. We are proud to carry on the tradition of leadership and the pioneering spirit of famous companies and brands that have shaped the way buses and coaches have to be designed and built: Fiat, OM, Orlandi in Italy, Berliet, Renault, Chausson, Saviem in France, Karosa in the Czech Republic, Magirus-Deutz in Germany and Pegaso in Spain, to name just a few. -

Minibus and People Carrier Operation Guidance

Minibus and People Carrier Operation Guidance Date: July 2014 Document summary Every care has been taken in assembling the information contained in this guidance. It is intended as a source of reference for drivers and those with a management responsibility for Minibus and People Carrier operation. There is a rapid pace of change in both legislation and recognised practice in the operation of these vehicles, and if there is any doubt about the guidance given in this guidance, please use the contact telephone numbers given to check the current position. Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 5 2. What is a minibus and who may drive one? ................................................... 5 2.1. Definition ......................................................................................................... 5 2.2. Licensing and Insurance ................................................................................. 5 2.3. Competence ................................................................................................... 6 2.4. Standards and Safety ..................................................................................... 6 2.5. Guidance for Drivers and Managers ............................................................... 6 2.6. Managers’ Responsibilities ............................................................................. 7 2.7. Drivers’ Responsibilities ................................................................................. -

Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual (Part B)

7UDQVLW&DSDFLW\DQG4XDOLW\RI6HUYLFH0DQXDO PART 2 BUS TRANSIT CAPACITY CONTENTS 1. BUS CAPACITY BASICS ....................................................................................... 2-1 Overview..................................................................................................................... 2-1 Definitions............................................................................................................... 2-1 Types of Bus Facilities and Service ............................................................................ 2-3 Factors Influencing Bus Capacity ............................................................................... 2-5 Vehicle Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-5 Person Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-13 Fundamental Capacity Calculations .......................................................................... 2-15 Vehicle Capacity................................................................................................... 2-15 Person Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-22 Planning Applications ............................................................................................... 2-23 2. OPERATING ISSUES............................................................................................ 2-25 Introduction.............................................................................................................. -

Technical Assistance for Capacity Building in Compilation and Analysis of the Fuel and Energy Balance for the Kyrgyz Republic (AHEF 113.KG) FINAL REPORT

Technical assistance for capacity building in compilation and analysis of the fuel and energy balance for the Kyrgyz Republic (AHEF 113.KG) FINAL REPORT INOGATE Technical Secretariat and Integrated Programme in support of the Baku Initiative and the Eastern Partnership energy objectives Contract No 2011/278827 A project within the INOGATE Programme Implemented by: Ramboll Denmark A/S (lead partner) EIR Development Partners Ltd. The British Standards Institution LDK Consultants S.A. MVV decon GmbH ICF International Statistics Denmark Energy Institute Hrvoje Požar INOGATE Technical Secretariat http://www.inogate.org Document title Technical assistance for capacity building in compilation and analysis of the fuel and energy balance for the Kyrgyz Republic (AHEF 113.KG), Final Report Document status Draft Name Date Prepared by Damir Pešut 01/12/2014 Alenka Kinderman Lončarevid Checked by Approved by This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publica- tion are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. INOGATE Technical Secretariat http://www.inogate.org Contents 1 Executive summary........................................................................................................ 9 2 Data collection and availability .................................................................................... 10 2.1 Input data for short-term energy demand forecast ............................................... 10 2.1.1 Air -

HDRO, Landlocked Report 2003

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics United Nations Development Programme Human Development Report Office OCCASIONAL PAPER Background paper for HDR 2003 Country case studies on the challenges facing landlocked developing countries Thomas Snow, Michael Faye, John McArthur and Jeffrey Sachs 2003 COUNTRY CASE STUDIES ON THE CHALLENGES FACING LANDLOCKED DEVELOPING COUNTRIES BY THOMAS SNOW, MICHAEL FAYE, JOHN MCARTHUR AND JEFFREY SACHS JANUARY 2003 Provisional Draft: Please do not cite without author's permission. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: We would like to acknowledge the valuable input of Guido Schmidt-Traub, Michael Salter and David Wright for their research assistance, of Malanding Jaiteh for his GIS data analysis and map construction, and of Nuño Limao and Anthony Venables for the use of their freight quote data. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1: INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 2 INDICATORS OF DEVELOPMENT................................................................................... 3 Landlocked Countries and Their Maritime Neighbours ......................................... 3 Measures of Relative Human Development Amongst Landlocked States ............. 5 Measures of Relative Landlockedness.................................................................... 6 PART 2: OBSERVATIONS FROM -

A Review of Accidents and Injuries to Road Transport Drivers TE--WE-10-004-EN-N

ISSN 1831-9351 A review of accidents and injuries to road transport drivers TE--WE-10-004-EN-N TE--WE-10-004-EN-N Authors European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) Sarah Copsey (project manager) Members of EU-OSHA Topic Centre – Working Environment Nicola Christie, RCPH, UK Linda Drupsteen, TNO, The Netherlands Jakko van Kampen, TNO, The Netherlands Lottie Kuijt-Evers, TNO, The Netherlands Ellen Schmitz-Felten, KOOP, Germany Marthe Verjans, Prevent, Belgium Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers, or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found on the cover of this publication. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2010 ISBN -13: 978-92-9191-355-8 doi:10.2802/39714 © European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, 2010 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. A REVIEW OF ACCIDENTS AND INJURIES TO ROAD TRANSPORT DRIVERS A review of accidents and injuries to road transport drivers Table of contents 1. Introduction....................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Objective of this report............................................................................................................3 1.2. Methodology ...........................................................................................................................3