Ice Candy Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Group Housing

LIST OF ALLOTED PROPERTIES DEPARTMENT NAME- GROUP HOUSING S# RID PROPERTY NO. APPLICANT NAME AREA 1 60244956 29/1013 SEEMA KAPUR 2,000 2 60191186 25/K-056 CAPT VINOD KUMAR, SAROJ KUMAR 128 3 60232381 61/E-12/3008/RG DINESH KUMAR GARG & SEEMA GARG 154 4 60117917 21/B-036 SUDESH SINGH 200 5 60036547 25/G-033 SUBHASH CH CHOPRA & SHWETA CHOPRA 124 6 60234038 33/146/RV GEETA RANI & ASHOK KUMAR GARG 200 7 60006053 37/1608 ATEET IMPEX PVT. LTD. 55 8 39000209 93A/1473 ATS VI MADHU BALA 163 9 60233999 93A/01/1983/ATS NAMRATA KAPOOR 163 10 39000200 93A/0672/ATS ASHOK SOOD SOOD 0 11 39000208 93A/1453 /14/AT AMIT CHIBBA 163 12 39000218 93A/2174/ATS ARUN YADAV YADAV YADAV 163 13 39000229 93A/P-251/P2/AT MAMTA SAHNI 260 14 39000203 93A/0781/ATS SHASHANK SINGH SINGH 139 15 39000210 93A/1622/ATS RAJEEV KUMAR 0 16 39000220 93A/6-GF-2/ATS SUNEEL GALGOTIA GALGOTIA 228 17 60232078 93A/P-381/ATS PURNIMA GANDHI & MS SHAFALI GA 200 18 60233531 93A/001-262/ATS ATUULL METHA 260 19 39000207 93A/0984/ATS GR RAVINDRA KUMAR TYAGI 163 20 39000212 93A/1834/ATS GR VIJAY AGARWAL 0 21 39000213 93A/2012/1 ATS KUNWAR ADITYA PRAKASH SINGH 139 22 39000211 93A/1652/01/ATS J R MALHOTRA, MRS TEJI MALHOTRA, ADITYA 139 MALHOTRA 23 39000214 93A/2051/ATS SHASHI MADAN VARTI MADAN 139 24 39000202 93A/0761/ATS GR PAWAN JOSHI 139 25 39000223 93A/F-104/ATS RAJESH CHATURVEDI 113 26 60237850 93A/1952/03 RAJIV TOMAR 139 27 39000215 93A/2074 ATS UMA JAITLY 163 28 60237921 93A/722/01 DINESH JOSHI 139 29 60237832 93A/1762/01 SURESH RAINA & RUHI RAINA 139 30 39000217 93A/2152/ATS CHANDER KANTA -

Unpaid Dividend-16-17-I2 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 737532.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE PLOT NO 10 AIYSSA GARDEN IN301637-41195970- Amount for unclaimed and A BALAN NA LAKSHMINAGAR MAELAMAIYUR INDIA Tamil Nadu 603002 400.00 24-Feb-2024 0000 unpaid dividend -

India Progressive Writers Association; *7:Arxicm

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 124 936 CS 202 742 ccpp-.1a, CsIrlo. Ed. Marxist Influences and South Asaan li-oerazure.South ;:sia Series OcasioLal raper No. 23,Vol. I. Michijar East Lansing. As:,an Studies Center. PUB rAIE -74 NCIE 414. 7ESF ME-$C.8' HC-$11.37 Pius ?cstage. 22SCrIP:0:", *Asian Stud,es; 3engali; *Conference reports; ,,Fiction; Hindi; *Literary Analysis;Literary Genres; = L_tera-y Tnfluences;*Literature; Poetry; Feal,_sm; *Socialism; Urlu All India Progressive Writers Association; *7:arxicm 'ALZT:AL: Ti.'__ locument prasen-ls papers sealing *viithvarious aspects of !',arxi=it 2--= racyinfluence, and more specifically socialisr al sr, ir inlia, Pakistan, "nd Bangladesh.'Included are articles that deal with _Aich subjects a:.the All-India Progressive Associa-lion, creative writers in Urdu,Bengali poets today Inclian poetry iT and socialist realism, socialist real.Lsm anu the Inlion nov-,-1 in English, the novelistMulk raj Anand, the poet Jhaverchan'l Meyhani, aspects of the socialistrealist verse of Sandaram and mash:: }tar Yoshi, *socialistrealism and Hindi novels, socialist realism i: modern pos=y, Mohan Bakesh andsocialist realism, lashpol from tealist to hcmanisc. (72) y..1,**,,A4-1.--*****=*,,,,k**-.4-**--4.*x..******************.=%.****** acg.u.re:1 by 7..-IC include many informalunpublished :Dt ,Ivillable from othr source r.LrIC make::3-4(.--._y effort 'c obtain 1,( ,t c-;;,y ava:lable.fev,?r-rfeless, items of marginal * are oft =.ncolntered and this affects the quality * * -n- a%I rt-irodu::tior:; i:";IC makes availahl 1: not quali-y o: th< original document.reproductiour, ba, made from the original. -

Amrita Pritam: the Revenue Stamp and Harivanshraibachchan: in the Afternoon of Time • Chapter III

Chapter Three Amrita Pritam: The Revenue Stamp and HarivanshRaiBachchan: In the Afternoon of Time • Chapter III (i) AmritaPritam '.The Revenue Stamp (ii) Hariwansh Rai Bachchan: In the Afternoon of Time The present chapter discusses those two writers who have made a mark in the Hterature of their regional languages, and consequently in India and abroad. Amrita Pritam is the first woman writer in the Punjabi literature emerged as a revolutionary poet and novelist who illuminated the predicament of women caused by shackles of traditions and patriarchy. Harvansh Rai Bachchan is the important name in the movement of 'Nayi Kavita'. He created a new wave of poetry among the admirers by his book Madhushala. With the publication of this book, he became one of the most admired poets in Hindi literary world. Amrita Pritam was a prolific writer and a versatile genius. She published more than 100 books of poetry, fiction, biographies, essays, translations of foreign writers' works, such as Bulgarian poets Iran Vazovand Haristobotev, a Hungarian poet Attila Josef etc., as well as a collection of Punjabi folk songs and autobiographies. Apart from The Revenue Stamp, she wrote one more autobiography Aksharon Ke Sayen (Shadows of Words) published in 1999.She was a rebel who lived her life in her own way with utmost intensity. This intensity, this passion is the soul of her writing. Before we plunge into a detailed discussion of her autobiography vis-a-vis her writings, it is useful to understand how she grew as an individual, what forces shaped her character and her mind, which people she learned from and grew as a writer. -

District Disaster Management Plan, (District Amritsar) 2020-2021

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN, (DISTRICT AMRITSAR) 2020-2021 Gurpreet Singh Khaira, IAS Deputy Commissioner, Amritsar 1 Index: S.No. Department name Page no. 1 Animal Husbandry 3-10 2 Civil Defence 11-129 3 Commissioner of Police 130-150 4 DEO(Elementary & Secondary) 151-153 5 DDPO 154-155 6 District Public Relations Officer 156-158 7 Fire Brigade 159-165 8 Municipal Corporation 166-181 9 Punjab State Power Corporation Limited(PSPCL) 182-185 10 General Manager, Roadways, Amritsar-I 186-187 11 General Manager, Roadways, Amritsar-II 188-189 12 Sub Divisional Magistrate, Amritsar-II 190-192 13 Senior Superintendent of Police, Amritsar(Rural) 193-216 14 Sub Divisional Magistrate, Baba Bakala Sahib 217-224 15 Municipal Corporation(Health Branch) 225-229 16 Civil Surgeon 230-254 17 Sub Divisional Magistrate, Ajnala 255-257 2 ANIMAL HUSBANDRY 3 Sr Name of Veterinary VETY. OFFICER NAME PHONE Name of Vety. Inspector/ PHONE PHONE No. Hospital NUMBER RVP NUMBER Name of class IV NUMBER 1 CVH MUDHAL DR. DARSHAN LAL 9814173841 Lakhwinder Singh 9780836312 Devi Dass 9814657904 2 CVH KHALSA COLLEGE DR. HARWINDER SINGH 8968988665 9914538865 SANDHU Bhupinder Singh 3 CVH CHATTIWIND DR. KULDEEP SINGH 9872629960 Vikramjit 8146599751 4 CVH WADALA BHITTEWAD DR. AMANDEEP SINGH PANNU 8146878662 Sukhchain Singh 9417317371 Champa Devi 9501388580 5 CVH BOHRU DR . HARJOT SINGH 9464264237 BALKAR NAYYAR 8427054422 Jaswant Singh 9501676035 6 CVH MANDIALA DR. JATINDER PAL SINGH 9876107789 Paramjit Singh 97792 61008 Tarsem Singh 9855380830 7 CVH MIRAKOT DR. GURDEEP SINGH 9815102003 Sarbjit Singh 8968688669 Amanpreet singh 9855139148 8 CVH GILLWALI DR. MANPREET KAUR 9872664776 Karanbir Singh 9914067649 Dilbag Singh 8728098181 9 CVH ATTARI DR. -

Ahb2017 18112016

iz'kklfud iqfLrdk Administrative Hand Book 2017 Data has been compiled based on the information received from various offices. For any corrections/suggestions kindly intimate at the following address: DIRECTORATE OF INCOME TAX (PR,PP&OL) 6th Floor, Mayur Bhawan, Connaught Circus, New Delhi - 110001 Ph: 011-23413403, 23411267 E-mail : [email protected] Follow us on Twitter @IncomeTaxIndia fo"k; lwph General i`"B la[;k Calendars 5 List of Holidays 7 Personal Information 9 The Organisation Ministry of Finance 11 Central Board of Direct Taxes 15 Pr.CCsIT/Pr.DsGIT and Other CCsIT/DsGIT of the respective regions (India Map) 26 Key to the map showing Pr.CCsIT/Pr.DsGIT and Other CCsIT/DsGIT of the respective regions 27 Directorates General of Income-Tax DsGIT at a glance 28 Administration 29 Systems 32 Logistics 35 Human Resource Development (HRD) 36 Legal & Research 38 Vigilance 39 Risk Assessment 42 Intelligence & Criminal Investigation 42 Training Institutes Directorate General of Training (NADT) 47 Regional Training Institutes 49 Directorate General of Income Tax (Inv.) 53 Field Stations Pr. CCsIT at a glance 77 A - B 79-92 C 93-99 D - I 100-119 J - K 120-135 L - M 135-151 N - P 152-159 R - T 160-167 U - V 167-170 3 Alphabetical List of Pr. CCsIT/Pr. DsGIT & CCsIT/DsGIT 171 Rajbhasha Prabhag 173 Valuation Wing 179 Station Directory 187 List of Guest Houses 205 Other Organisations Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) 217 ITAT 217 Settlement Commission 229 Authority for Advance Rulings 233 Appellate Tribunal for Forfeited Property -

Yashpal (Yaśpāl)

Yashpal (Yaśpāl) Leben: Neben Agyeya und Jainendra Kumar zählt Yashpal (1903-1976) zu den drei „Revoluzzer-Autoren“ der Hindi-Literatur, die in ihren Werken den Kampf um die Unabhängigkeit in den 1930er bis 1950er Jahren verarbeiteten. Yashpal wurde 1903 in Firozpur (Panjab, Nordindien) Briefmarke zum Gedenken an Yashpal (2003) geboren. In seiner Jugend war er überzeugter Gandhi- Anhänger und warb als Aktivist unter der Landbevölkerung für die Non-Cooperation- Bewegung. Später, während seiner Zeit als Student am Punjab National College (Lahore) wandte er sich aus Enttäuschung über die Politik des Indian National Congress der radikale- ren Bewegung der Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) zu, die den gewalt- samen Widerstand als den wirkungsvolleren Weg zur Befreiung Indiens von den Briten pro- klamierte. Auf dem College lernte er Bhagat Singh und Sukhdev Thapar kennen, zwei wichti- ge Mitglieder der HSRA, die später als Märtyrer-Revolutionäre Berühmtheit erlangen sollten. Zwischen 1932 und 1938 saß er wegen eines versuchten Bombenanschlags in Haft. Neben seiner Tätigkeit als Aktivist und vielfach ausgezeichneter Autor war er auch Journalist, Kriti- ker, Herausgeber, Dramatiker und Übersetzer. Werk: Yashpal wird in der Nachfolge Premchands gesehen, weil er über die Ungerechtigkeiten in- nerhalb der indischen Gesellschaft schrieb. Jedoch verband er seinen sozialkritischen Realis- mus stärker mit urbanen Themen und marxistischen Sichtweisen, die das neu erweckte Klas- senbewusstsein, die Aufdeckung religiöser Doppelmoral und Kastenvorurteile ins Zentrum stellten. Seine Sympathien für den Marxismus dürften auch ein Grund dafür sein, warum viele seiner Werke ins Russische übersetzt worden sind. Der Roman Dada Kamred (1941) handelt etwa von indischen Kommunisten in den späten 1930er und frühen 1940er Jahren und setzt sich kritisch mit Fragen des gewaltsamen Widerstands sowie mit dem moralischen Dilemma auseinander, die Familie für die Revolution zu verlassen. -

List of Employees in Bank of Maharashtra As of 31.07.2020

LIST OF EMPLOYEES IN BANK OF MAHARASHTRA AS OF 31.07.2020 PFNO NAME BRANCH_NAME / ZONE_NAME CADRE GROSS PEN_OPT 12581 HANAMSHET SUNIL KAMALAKANT HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 13840 MAHESH G. MAHABALESHWARKAR HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182402.87 PENSION 14227 NADENDLA RAMBABU HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 14680 DATAR PRAMOD RAMCHANDRA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182116.67 PENSION 16436 KABRA MAHENDRAKUMAR AMARCHAND AURANGABAD ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 168872.35 PENSION 16772 KOLHATKAR VALLABH DAMODAR HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182402.87 PENSION 16860 KHATAWKAR PRASHANT RAMAKANT HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 183517.13 PENSION 18018 DESHPANDE NITYANAND SADASHIV NASIK ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 169370.75 PENSION 18348 CHITRA SHIRISH DATAR DELHI ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 166230.23 PENSION 20620 KAMBLE VIJAYKUMAR NIVRUTTI MUMBAI CITY ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 169331.55 PENSION 20933 N MUNI RAJU HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 172329.83 PENSION 21350 UNNAM RAGHAVENDRA RAO KOLKATA ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 21519 VIVEK BHASKARRAO GHATE STRESSED ASSET MANAGEMENT BRANCH GENERAL MANAGER 160728.37 PENSION 21571 SANJAY RUDRA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182204.27 PENSION 22663 VIJAY PRAKASH SRIVASTAVA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 179765.67 PENSION 11631 BAJPAI SUDHIR DEVICHARAN HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13067 KURUP SUBHASH MADHAVAN FORT MUMBAI DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13095 JAT SUBHASHSINGH HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13573 K. ARVIND SHENOY HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 164483.52 PENSION 13825 WAGHCHAVARE N.A. PUNE CITY ZONE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 155576.88 PENSION 13962 BANSWANI MAHESH CHOITHRAM HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 14359 DAS ALOKKUMAR SUDHIR Retail Assets Branch, New Delhi. -

Viswanatha Satyanarayana Ramayana Kalpavruksham Baala Kanda Pdf Download Free Ku Factor

viswanatha satyanarayana ramayana kalpavruksham baala kanda pdf download free Ku Factor. there are important thing, and not important ones. the most important thing for you is to find a website where you can download pdf files for free. the website must be free and without limits. if you don't know a website i can suggest one. VISWANATHA SATYANARAYANA RAMAYANA PDF. Srimadramayana Kalpavruksham (Telugu) Hardcover – by Viswanadha Satyanarayana (Author). out of 5 stars 3 Viswanatha Paperback. Thu, 18 Oct GMT viswanatha satyanarayana ramayana pdf – Some noteworthy examples of these additional renderings of the. Ramayana tale . More Articles Srimadramayana kalpavruksham – Kishkindakanda by Viswanadha · Srimadramayana kalpavruksham-Yuddakanda by Viswanadha · Vedavathi. Author: Voodoogore Kigajin Country: Papua New Guinea Language: English (Spanish) Genre: Photos Published (Last): 5 August 2015 Pages: 135 PDF File Size: 8.23 Mb ePub File Size: 16.64 Mb ISBN: 682-3-54296-835-5 Downloads: 48411 Price: Free* [ *Free Regsitration Required ] Uploader: Tok. His literary works include 30 poems, 20 plays, 60 novels, 10 critical estimates, Khand kavyas, 35 short stories, three playlets, 70 essays, 50 radio plays, 10 essays in English, 10 works is Sanskrit, three translations, introductions and forewords as well as radio talks. Bonding among villagers beyond castes and social barriers, Beauty of village life were also shaped his thought and ideology later. Wagle Prem Nath Wahi Yashpal. Viswanatha Satyanarayana is son of Shobhanadri, a Brahmin Landlord who later impoverished due to his over genourosiry and Charity and his wife Parvathi. Archived from the original on 13 October He went to Veedhi Badi literal tr: During his childhood, Traditional performers of several Street folk art forms attracted and educated Satyanarayana in many ways. -

Part - I Ancient Poetry, Short Stories & Functional Hindi

Part - I Ancient Poetry, Short Stories & Functional Hindi Course Code: 15-18/18101 Credit – 03 Semester - I Hours: 75 Learning Objective: To inculcate social and moral values, national integration and universal brotherhood through the Hindi literature component prescribed in the paper. Students are expected to know the office and business procedure, official terminology and correspondence, Noting & drafting. UNIT 1- Hours: 15 1. KABIR KE DOHE 2. SHARANDATA (AGEYA) 3. BANKING LETTER, TAX & INSURANCE LETTER UNIT -2 Hours: 15 1. SURDAS KE PAD (BRAMARGEET) 2. PARDA (YASHPAL) 3. TECHNICAL WORDS UNIT – 3 Hours: 15 1. TULASIDAS KE PAD (VINAY KE PAD) 2. BHOLARAM KA JEEV ( HARISHANKER PARSAI ) 3. BOOK ORDER & CANCELATION LETTER UNIT -4 Hours: 15 1. RAHIM KE DOHE 2. BIHARI KE DOHE 3. CHIEF KI DAVAT ( BHEESMA SAHNI ) UNIT – 5 Hours: 15 1. BHUSHAN KE PAD 2. THIRUKKURAL 3. VAAPSI (USHA PRIYAMVADA) Prescribed Text: 1. Kavya sourabh (Dr. Hriday Narayan Pandey) 2. Nagar kathayen (Dr. Balendu shekhar Tiwari) 3. Vyavsayik Hindi: (Prof. Saiyad Rahamattullah) Part – I, PROSE, ONE ACT PLAY & LETTER WRITING Course Code: 15-18/18202 Credit – 03 Semester - II Hours: 75 Learning Objective: To give an impact into life and society through Essays and One Act Play to help student understand the contemporary social and national issues. Gain knowledge Through different types of official letters. UNIT 1- Hours: 15 1. YUVAKON KA SAMAJ MEIN STHAN (NARENDRA DEV) 2. DEEPDAAN (DR. RAMKUMAR VERMA) 3. OFFICE ORDER UNIT 2 - Hours: 15 1. SHIKSHA KA UDDESHYA (SHAMPURNA NAND) 2. REEDH KI HADDI (JAGDEESH CHANDRA MATHUR) 3. CIRCULAR UNIT – 3 Hours: 15 1. -

Saurashtra University Library Service

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Etheses - A Saurashtra University Library Service Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93) Shaikh, Firoz A., 2006, “The partition and its versions in Indian English Novels: A Critical Study”, thesis PhD, Saurashtra University http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu/id/829 Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Saurashtra University Theses Service http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu [email protected] © The Author THE PARTITION AND ITS VERSIONS IN INDIAN ENGLISH NOVELS: A CRITICAL STUDY A DISSERTATION TO BE SUBMITTED TO SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY, RAJKOT FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH SUPERVISED BY SUBMITTED BY Dr. Jaydipsinh Dodiya Mr. Firoz A. Shaikh Associate Professor, Senior Lecture & Head, Smt. S.H.Gardi Institute of English Department of English, and Comparative Literary Studies, Late Shri N.R.Boricha Saurashtra University, EducationTrust Sanchalit Rajkot-360005 Arts & Commerce College, Mendarda-362 260 2006 I STATEMENT UNDER UNI. O. Ph.D. 7. I hereby declare that the work embodied in my thesis entitled as “THE PARTITION AND ITS VERSIONS IN INDIAN ENGLISH NOVELS: A CRITICAL STUDY”, prepared for Ph.D. -

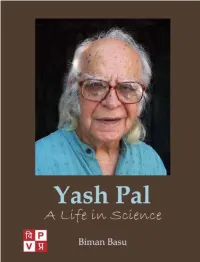

Prof Yash Pal: a Life in Science

Yash Pal A Life in Science Yash Pal A Life in Science Biman Basu VIGYAN PRASAR Published by Vigyan Prasar Department of Science and Technology A-50, Institutional Area, Sector-62 NOIDA 201 307 (Uttar Pradesh), India (Regd. Office: Technology Bhawan, New Delhi 110016) Phones: 0120-2404430-35 Fax: 91-120-2404437 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.vigyanprasar.gov.in Copyright: 2006 by Vigyan Prasar All rights reserved Yash Pal: A Life in Science by Biman Basu Cover photograph by: Biman Basu Cover design and typesetting: Pradeep Kumar Production Supervision: Biman Basu and Subodh Mahanti ISBN: 81-7480-128-6 (Hardbound) 81-7480-129-4 (Paperback) Price : Rs. 225 (Hardbound) Rs. 150 (Paperback) Printed by Rakmo Press Private Limited C-59, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi - 110 020 Content Foreword ...................................................................................................... vii Preface .......................................................................................................... ix Chapter 1 : Early Years......................................................................... 1 Chapter 2 : Turbulent Days ................................................................. 5 Chapter 3 : TIFR and Balloon Flights............................................... 11 Chapter 4 : The MIT Experience ....................................................... 31 Chapter 5 : In Quest of Cosmic Particles ......................................... 45 Chapter 6 : The Magic of SITE .........................................................