Thomson, Matthew Ian Malcolm (2009) Military Computer Games and the New American Militarism: What Computer Games Teach Us About War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Philosophy for Physics 100 at IDBSU Dewey Dykstra Dept

Course Philosophy for Physics 100 at IDBSU Dewey Dykstra Dept. of Physics Boise State University This explanation, written by Dr. Dewey Dykstra of Boise State for a course he teaches, details a philosophy that is very similar to what is behind this course at BHSU. It is offered as “something to think about”. Dr. Dykstra’s original document has been edited to remove course-specific information, but the general ideas that govern the course you are taking are practically the same. - Andy Johnson Welcome to what promises to be one of the more interesting courses you will take at Boise State. It is almost certain to be different than any you have taken in science. The intent of this course is for you to examine and develop with your classmates an understanding of some physical phenomena and to personally experience the process of making sense of the physical world. There will not be lectures in the normal sense. As such the discussion is not easily summarized as you might a normal lecture. It is very important that you participate continuously in the discussion in class. The course is heavily based on experiences in lab, therefore it is also very important that you attend every lab. Since the course is neither based on a textbook nor on standard lectures, if you have not participated in lab, what happens in the class discussion will not make sense or be of any real value to you on exams. A QUOTATION CONSISTENT WITH THE FOUNDATIONS OF THIS COURSE: "[Ian] Malcolm had long been impatient with the arrogance of his scientific colleagues. -

Jurassic Park

DAWN OF THE EXTINCTION: J U R A S S I C P A R K (AN ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY) JUNE 29, 2008 FIRST DRAFT BY: JOSH CLAIR OPEN ON: DARKNESS. FADE TO: A puddle of water lay still in a muddy jungle. We can here the crickets chirp, as well as other animals. Then, they start to fade away until only the crickets are left chirping. Immediately the crickets stop and the puddle becomes active after a loud thump makes rings in the puddle. CUT TO: 1 EXT. COSTA RICA - NIGHT 1 The sky is dark but clear. PAN DOWN To see the top of trees belonging to a jungle. This is the edge of the jungle though and beside it is a grassy field and a small one-story house. SUBTITLE HEREDIA, COSTA RICA Outside, all is quiet as a slight breeze picks up. Suddenly the ferns lightly rustle and a soft snarl can be heard. But is this only tricks of the wind? CUT TO: 2 INT. HOUSE - DARK 2 Inside the house. All is dark, the occupants long asleep. In one bedroom, a man and woman sleep soundlessly. Suddenly, we are so aware of the quietness that we can only notice the sounds that are not supposed to be there. CUT TO: Still inside the house, but looking at the main door. Suddenly the doorknob starts to rattle and slowly turn. CUT BACK TO: Man and Woman sleeping. The sound of the door creaking open is heard, but they still sleep. Something can be heard walking across the floor. -

The Cultural Ambivalences of Family in the Cinema of Steven Spielberg

‘Steven Phone Home’ The Cultural Ambivalences of Family in the Cinema of Steven Spielberg Suzanne Stuart PhD Thesis University of New South Wales 2011 Contents Preface and Acknowledgements iii Introduction: Family Consumption 1 • Spielberg’s Families in the Twilight Zone • Minority Report? Spielberg and the Family in Critical Literature • Close Encounters of the Familial Kind Part One: The Private Sphere of Hearth and Home 1. The Hook within the (Impossible) Family: Standing on the Outside, Looking In – Ideology, Fantasy and Desire 51 • ‘I Fought the Law, and the Law Won’: Catch Me if You Can • ‘Freud’s Robots’: Artificial Intelligence: A.I. • Conclusion: Artificial Resolution 2. The Lost World of ‘Home’: Suburbia, Family Ghosts, and Alienation in Domesticity 106 • Domestic Off-Screen Space in Duel: ‘not the boss in my house’ • Alienation in E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial – The Suburbs Become Home • ‘The grass grows greener on every side’: Avoiding Binaries in the Fantasy Suburb of Poltergeist • ‘They’re here’: The Penetration of the Public/Private Home in Poltergeist • The Gendered Home - ‘Ask Dad’ • Implosion: The Death Drive of the Suburban Home • Conclusion: Not Quite Home Yet Part Two: Rhetorical Families in the Public Sphere 3. A Leap of Faith: What Lies Beneath the Word of the Father? Representing God, Religion and the Family 162 • Close Encounters of the Third Kind: Melodramatic Masculinity in (Domestic) Space – Mashed Potatoes and Spirituality • The Color Purple and the Shadow of Incest – Obscene Fathers and Father-Gods • A Radio to God? Raiders of the Lost Ark and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: Postmodernism, Religious Nostalgia and the (Impossible) Father- God • Conclusion: Chasms and Symbols 4. -

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1Background of Research

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1Background of Research Environment, technology and human have never been separated.They were growing together. Great achievements in the history of humanity would have never existed without them. In literature, this interrelationship can be depicted in thescience fiction genre which displays technology ina new imaginary future or a new technology that may influence new inventions, nowadays. In A Glossary of Literary Term, M.H Abrams stated, “These terms encompass novels and short stories that represent an imagined reality that is radically different in its nature and functioning from the world of our ordinary experience. Often the setting is another planet, or this earthprojected into the 112, or an imagined parallel universe” (Abrams 278) Many authors inserted technology and environment of their work to their writings. One of them is an American famous author, Michael Crichton, a writing name of John Michael Crichton. He was born on October 23rd, 1942, in Chicago, Illinois. Some of his novels were adapted to motion pictures such as Rising Sun in 1993 after it was published in 1992, The Lost World in 1995, filmed in 1997, and Disclosure in 1994. He died in the age of 66 on November 4th, 2008, in Los Angeles, California. He was a student of Harvard Medical School when he wrote a best-seller novel, The Andromeda Strain in 1969. Crichton won Emmy Award, Writer's Guild of America Award and Peabody Award as validation of his achievement. During his life, he wrote 27 fiction novels, 10 short stories, and 4 non-fiction works as social criticism. -

The Lost World

LEVEL 4 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme The Lost World Michael Crichton Lewis Dodgson and George Baselton are corrupt EASYSTARTS scientists who work for Biosyn, a medical company. They are talking to Ed James, whom Dodgson pays to spy for him. James tells them that Levin has disappeared in Costa Rica. Malcolm receives a packet from Costa Rica with skin LEVEL 2 from the animal Levine found—skin that may be from a dinosaur. At a school where Levine teaches, two young students wonder where he is. The students, Kelly and LEVEL 3 Arby, go to the factory of Dr. Thorne, who is preparing the equipment for Levine’s expedition. Thorne tells them he doesn’t know where Levine is. Meanwhile, Levine has LEVEL 4 landed on a Pacific island called Isla Sorna, a “lost world” with giant plants and trees—and dinosaurs. While Kelly and Arby are at Thorne’s factory, Levine calls. He tells LEVEL 5 About the author them that he is on an island, and something wants to kill Born in Chicago, in the United States, in 1942, Michael him—and then the phone goes dead. Crichton was educated at Harvard College and Harvard Chapters 4–6: Thorne, Kelly, and Arby go to Levine’s LEVEL 6 Medical School. At the age of only twenty-three, he was a apartment. They discover that Levine was looking visiting lecturer in anthropology at Cambridge University. for a place called “Site B” that is connected to InGen. While training as a doctor he was also writing thrillers, Arby finds an old InGen computer that is filled with including the science fiction novel, The Andromeda Strain, information. -

The Representation of Femininity and Masculinity in Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park and Colin Trevorrow`S Jurassic World

Gender Hybrids: The Representation of Femininity and Masculinity in Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park and Colin Trevorrow`s Jurassic World Grado en estudios ingleses – 4º Curso Departamento de filología inglesa y alemana y traducción e interpretación Autora: Ainhize Ayerbe Irigoyen Tutora: Amaya Fernández Menicucci Curso Académico 2017/18 Abstract Gender representation in Hollywood action cinema has inevitably become the object of a wide debate among its critics. The history of film can be divided in different periods according to the way in which gender reflected and re-produced what was fashionable in a given sociocultural and historical context. The representation of gender in Hollywood mainstream action cinema from the 1990s to the 2010s seems, indeed, to mirror western standards. This paper aims at examining the representation of gender in two specific action films, Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993) and Colin Trevorrow’s Jurassic World (2015), and at analyzing possible differences in gender representation after a time span of twenty-two years. To that end, the analysis will be approached from a gender perspective, in particular, that of such experts in the cinematic representation of masculinities and femininities as Anne Gjelsvik and Elizabeth Hills, among others. Jurassic Park, the first installment of the franchise, seems to be imbued with the 1990s cinematic standards, which, in turn, are influenced by the politics and technological developments of that era. In the wake of Reagan’s and Bush Sr.’s conservatism, the film still mainly focuses on a male character, thus emphasizing his accomplishments, while leaving his female counterpart in the background. Likewise, and despite the fact that 2015 film Jurassic World is starred by a powerful female character, Trevorrow’s film is not devoid of lingering stereotypical gender representations. -

Jurassic Park Michael Crichton

Jurassic Park Michael Crichton Online Information For the online version of BookRags' Jurassic Park Premium Study Guide, including complete copyright information, please visit: http://www.bookrags.com/studyguide-jurassic-park/ Copyright Information ©2000-2007 BookRags, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. The following sections of this BookRags Premium Study Guide is offprint from Gale's For Students Series: Presenting Analysis, Context, and Criticism on Commonly Studied Works: Introduction, Author Biography, Plot Summary, Characters, Themes, Style, Historical Context, Critical Overview, Criticism and Critical Essays, Media Adaptations, Topics for Further Study, Compare & Contrast, What Do I Read Next?, For Further Study, and Sources. ©1998-2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Encyclopedia of Popular Fiction: "Social Concerns", "Thematic Overview", "Techniques", "Literary Precedents", "Key Questions", "Related Titles", "Adaptations", "Related Web Sites". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Guide to Literature for Young Adults: "About the Author", "Overview", "Setting", "Literary Qualities", "Social Sensitivity", "Topics for Discussion", "Ideas for Reports and Papers". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. All other sections in this Literature Study Guide are owned and copywritten by BookRags, Inc. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. -

Film and Literature Summer Assignment Novel: Jurassic Park By Michael Crichton Film

Film and Literature Summer Assignment Novel: Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton Film: Jurassic Park (1993), directed by Steven Spielberg Welcome to Film and Lit! For your summer assignment, please complete the following for Jurassic Park and its film adaptation. You can read the book or watch the film first -- whichever makes the assignment easier for you to complete. It is due in its entirety on the first day of school. 1. Read the novel. You will need a hard copy that you can write in and bring to school. As you read, annotate the novel (see example below), focusing on characterization. Notes will be checked at the beginning of the year. What qualities and attributes define the characters? What goals drive their actions? How do they interact with each other? What are their roles in the story? 2. Watch the film adaptation. As you do so, take notes, again focusing on characterization. Look at the above questions and consider them again as you watch the film. Pay attention to any changes that are made as the characters are portrayed in the film. You may handwrite or type your notes, but you should have the equivalent of one typed, double-spaced page at least. List your notes in an outline or bullet point form. Notes will be checked at the beginning of the year. 3. Compose a two-page response paper, typed and written in MLA format. In your paper, thoughtfully respond to the following two prompts. 1) Choose a major character in Jurassic Park (Alan Grant, John Hammond, Ellie Satler, Ian Malcolm, etc.). -

Dinosaur Representation in Museums

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State Museum Studies Theses History and Social Studies Education 12-2020 Dinosaur Representation in Museums: How the Struggle Between Scientific Accuracy and Pop Culture Affects the Public Perception of Mesozoic Non-Avian Dinosaurs in Museums Carla A. Feller State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College, [email protected] Advisor Noelle J. Wiedemer, M.A. First Reader Noelle J. Wiedemer, M.A. Second Reader Cynthia A. Conides, Ph.D. Department Chair Andrew D. Nicholls, Ph.D. Recommended Citation Feller, Carla A., "Dinosaur Representation in Museums: How the Struggle Between Scientific Accuracy and Pop Culture Affects the Public Perception of Mesozoic Non-Avian Dinosaurs in Museums" (2020). Museum Studies Theses. 27. https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/museumstudies_theses/27 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/museumstudies_theses Part of the Archival Science Commons, History Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons i Abstract This thesis examines the struggle of museums to keep up with swiftly advancing scientific discoveries relating to the study and display of Mesozoic (approximately 250 million years to 65 million years ago) non-avian dinosaurs. The paper will explore the history of dinosaur discoveries, their display methodologies in museums, and how pop culture, including movies and video games, have influenced museum displays and public perception over time. The lack of updated dinosaur exhibits in smaller local museums leads to disbelief, or an outright denial, of new information such as feathered dinosaurs. Entertainment, such as movies and video games that have non-avian dinosaurs as part of their presentation, are examined over the past thirty years to determine how accurate or inaccurate they are to the understanding of dinosaurs from their respective years. -

Introduction to Complexity Theory

Introduction to Complexity Theory Eric Fleischman March 3, 2017 Background • It is possible that you already know about Complexity Theory as the “butterfly effect” – For example, the Ian Malcolm character in the movie Jurassic Park. • Modern Complexity Theory dates from the work of Edward Lorenz, a MIT mathematician and meteorologist, in the 1960s. – While modeling atmospheric flows he discovered that minute changes in initial conditions resulted in widely different outcomes. – Merely because the precise origin of a specific event cannot be forecast does not mean that the likelihood of such an event cannot be predicted. • Complexity and the related field of chaos theory are two examples within nonlinear mathematics and critical state systems analysis – Climate, biology, solar flares, forest fires, traffic jams, and other natural and man-made behaviors (e.g., financial markets, dating) can all be described using complexity theory. • Complex systems all have behaviors in common, yet have dynamics unique to each domain. – Our textbook explains in the first paragraph on page 288 that most theoretical work in data communications assumes Poisson Traffic Models. This is why that theoretical work is demonstrably inaccurate (i.e., network traffic is self-similar (textbook page 737), not Poisson). This observation is well-recognized in Data Communications. However, it is the instructor’s personal opinion that should network modeling instead leverage complexity theory then that would produce superior results. That is why this topic is in the class notes. Basic Concepts • Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) has created a mathematical methods toolkit for solving complexity theory problems – Humans have always observed the outcome of complex systems but until computing power became large enough, complex dynamic system paths have not been observable in graphical form. -

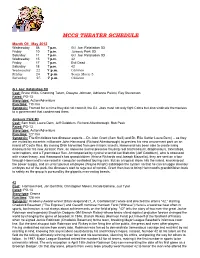

Mccs Theater Schedule

MCCS THEATER SCHEDULE Month Of: May 2013 Wednesday 08 7 p.m. G.I. Joe: Retaliation 3D Friday 10 7 p.m. Jurassic Park 3D Saturday 11 7 p.m. G.I. Joe: Retaliation 3D Wednesday 15 7 p.m. 42 Friday 17 7 p.m. Evil Dead Saturday 18 7 p.m. 42 Wednesday 22 7 p.m. Oblivion Friday 24 7 p.m. Scary Movie 5 Saturday 25 7 p.m. Oblivion G.I. Joe: Retaliation 3D Cast: Bruce Willis, Channing Tatum, Dwayne Johnson, Adrianne Palicki, Ray Stevenson Rated: PG-13 Story type: Action/Adventure Run time: 110 min Synopsis: Framed for a crime they did not commit, the G.I. Joes must not only fight Cobra but also vindicate themselves to a government that condemned them. Jurassic Park 3D Cast: Sam Neill, Laura Dern, Jeff Goldblum, Richard Attenborough, Bob Peck Rated: PG-13 Story type: Action/Adventure Run time: 127 min Synopsis: The film follows two dinosaur experts -- Dr. Alan Grant (Sam Neill) and Dr. Ellie Sattler Laura Dern) -- as they are invited by eccentric millionaire John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) to preview his new amusement park on an island off Costa Rica. By cloning DNA harvested from pre-historic insects, Hammond has been able to create living dinosaurs for his new Jurassic Park, an immense animal preserve housing real brachiosaurs, dilophosaurs, triceratops, velociraptors, and a Tyrannosaur Rex. Accompanied by cynical scientist Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum), who is obsessed with chaos theory, and Hammond's two grandchildren (Ariana Richards and Joseph Mazzello), they are sent on a tour through Hammond's new resort in computer controlled touring cars. -

Food Apocalypse Now: an Epistemological Understanding of the Coming Food Crisis Alexander SK Parker Depauw University

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 2015 Food Apocalypse Now: An Epistemological Understanding of the Coming Food Crisis Alexander SK Parker DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the Agricultural Economics Commons, and the Biosecurity Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Alexander SK, "Food Apocalypse Now: An Epistemological Understanding of the Coming Food Crisis" (2015). Student research. Paper 34. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [TYPE THE COMPANY NAME] Food Apocalypse Now An Epistemological Understanding of the Coming Food Crisis Alexander SK Parker 4/13/2015 Committee: Glen Kuecker, Brett O’Bannon, Christopher Marcoux Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge my parents who supported my all these years. I would like to acknowledge Annie DiBisceglie for her mental support. I would like to acknowledge Rachel Massoud, the greatest honors scholar drop out ever. I would like to acknowledge the Honors Scholar Program for four great years of learning and vibrant discussion. I would like to acknowledge my committee for helping me through this process. Finally, I would like to acknowledge my Sponsor, Glen Kuecker. Without you, this would not have been possible. 1 Introduction: Food Apocalypse Now In early 2007, Mexico experienced a 67% rise in corn prices, which drove up the price of tortillas and limited community access to 10,000 year food staple.