The Image of the Journalist and the News Media in the Feature Films Directed by Steven Spielberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF of This Issue

MlT's The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Cloudy, windy, 58°F (14°C) Tonight: Cloudy, drizzle, 52°F (11 0c) Newspaper Tomorrow: Cloudy, rainy, 58°F (14°C) Details, Page 2 Friday, October 20, 199 lIanrard, Duke Official New Dean of Student Life By Christopher L. Failing time to meet the staff of the Dean's tration and finance, strengths that things work here, my knowledge [of ASSOCIA TE NEWS EDITOR Office and prepare for the job. would help in the ongoing re-engi- M IT] makes me want to learn Margaret, R. Bates, an academic Bates said she had no knowledge neering of student services, she said. more," Bates said. and financial planning officer at concerning the amount of student Williams was "hired to provide Bates said her knowledge of the Harvard University and a former contact the job would allow versus leadership on academic issues. It Institute could be described as hav- vice provost of Duke University, the 'amount of administrative work, would be impossible for me to do ing MIT in her "peripheral vision was named to the new position of but she said she was looking for- this unless I had someone I could for most of my life," and is looking dean for student life on Tuesday. ward to the opportunity to work count on" in the dean of student life forward to "joining the community The appointment comes one year with students, faculty members, and position, she said. that Iadmire." She has worked with after former Dean for Undergradu- administrators. Both Williams and Bates MIT administrators in the past, and ate Education and Student Affairs expressed the importance of build- her husband received a doctorate rthur C. -

International Journal of Engineering, Social Justice, and Peace

International Journal of Engineering, Social Justice, and Peace Fall 2012 | Volume 1 | Number 2 ISSN 1927-9434 Editors Jens Kabo, Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden Usman Mushtaq, MSc Queen’s University, Canada Dean Nieusma, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, USA Donna Riley, Smith College, USA Editorial Board Asad Aziz, Colorado State University, USA Sylvat Aziz, Queen's University, Canada Margaret Bailey, Rochester Institute of Technology, USA Caroline Baillie, University of Western Australia, Australia Jenni Case, Cape Town University, South Africa George Catalano, Binghamton University, USA Mariano Fressoli, National University of Quilmes, Argentina Elizabeth Godfrey, University of Technology, Australia Rebekah Green, Western Washington University, USA Katy Haralampides, University of New Brunswick, Canada Jon Leydens, Colorado School of Mines, USA Juan Lucena, Colarado School of Mines, USA Darko Matovic, Queen's University, Canada Alice Pawley, Purdue University, USA Jane Pritchard, London School of Economics, United Kingdom Chris Rose, Rhode Island School of Design, United Kingdom Nasser Saleh, Queen's University, Canada Carmen Schifellite, Ryerson University, Canada Jen Schneider, Colorado School of Mines, USA Amy Slaton, Drexel University, USA Technical Assistance Nasser Saleh, Queen’s University, Canada Martin Wallace, University of Maine, USA International Journal of Engineering, Social Justice, and Peace esjp.org/publications/journal CONTENTS ARTICLES* GUEST INTRODUCTION TO SPECIAL ISSUE ON NAE’S GRAND CHALLENGES FOR ENGINEERING Great Problems of Grand Challenges: Problematizing Engineering’s Understandings of Its Role in Society 85–94 Erin Cech Engineering Improvement: Social and Historical Perspectives on the NAE’s “Grand Challenges” 95–108 Amy E. Slaton I Have Seen the Future! Ethics, Progress, and the Grand Challenges for Engineering 109–122 Joseph R. -

ZOOM- Press Kit.Docx

PRESENTS ZOOM PRODUCTION NOTES A film by Pedro Morelli Starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley Theatrical Release Date: September 2, 2016 Run Time: 96 Minutes Rating: Not Rated Official Website: www.zoomthefilm.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/screenmediafilm Twitter: @screenmediafilm Instagram: @screenmediafilms Theater List: http://screenmediafilms.net/productions/details/1782/Zoom Trailer: www.youtube.com/watch?v=M80fAF0IU3o Publicity Contact: Prodigy PR, 310-857-2020 Alex Klenert, [email protected] Rob Fleming, [email protected] Screen Media Films, Elevation Pictures, Paris Filmes,and WTFilms present a Rhombus Media and O2 Filmes production, directed by Pedro Morelli and starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar, Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley in the feature film ZOOM. ZOOM is a fast-paced, pop-art inspired, multi-plot contemporary comedy. The film consists of three seemingly separate but ultimately interlinked storylines about a comic book artist, a novelist, and a film director. Each character lives in a separate world but authors a story about the life of another. The comic book artist, Emma, works by day at an artificial love doll factory, and is hoping to undergo a secret cosmetic procedure. Emma’s comic tells the story of Edward, a cocky film director with a debilitating secret about his anatomy. The director, Edward, creates a film that features Michelle, an aspiring novelist who escapes to Brazil and abandons her former life as a model. Michelle, pens a novel that tells the tale of Emma, who works at an artificial love doll factory… And so it goes.. -

Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960S and Early 1970S

TV/Series 12 | 2017 Littérature et séries télévisées/Literature and TV series Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.2200 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s », TV/Series [Online], 12 | 2017, Online since 20 September 2017, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.2200 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series o... 1 Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy 1 In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, in a somewhat failed attempt to wrestle some high ratings away from the network leader CBS, ABC would produce a spate of supernatural sitcoms, soap operas and investigative dramas, adapting and borrowing heavily from major works of Gothic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The trend began in 1964, when ABC produced the sitcom The Addams Family (1964-66), based on works of cartoonist Charles Addams, and CBS countered with its own The Munsters (CBS, 1964-66) –both satirical inversions of the American ideal sitcom family in which various monsters and freaks from Gothic literature and classic horror films form a family of misfits that somehow thrive in middle-class, suburban America. -

L3702 LETHAL WEAPON 2 (USA, 1989) (Other Titles: Arma Lethale 2; Arme Fatale 2; Brennpunkt L.A.; Dodbringende Veben 2)

L3702 LETHAL WEAPON 2 (USA, 1989) (Other titles: Arma lethale 2; Arme fatale 2; Brennpunkt L.A.; Dodbringende veben 2) Credits: director, Richard Donner ; writer, Jeffrey Boam. Cast: Mel Gibson, Danny Glover, Joe Pesci, Joss Ackland. Summary: Police thriller set in contemporary Los Angeles. Detectives Riggs (Gibson) and Murtaugh (Glover) must guard a free-wheeling witness (Pesci) in a drug money laundering scheme run by South African diplomats. A comedy of car chases, gun battles, and under-water escapes. Ansen, David. “The arts: Movies: Gibson and Glover return: ‘Lethal weapon 2’ serves up sadism with a smile” 114 Newsweek (Jul 17, 1989), p. 53. [Reprinted in Film review annual 1990] Avins, Mimi. “Shot by shot” Premiere 2/12 (Aug 1989), p. 72-6. Baumann, Paul D. “Screen: Scorching the screen” Commonweal 116 (Oct 6, 1989), p. 529-30. Blair, Iain. “Movies: Mel’s lethal appeal: He’s got killer looks, but shucks, Gibson’s just one of the guys” Chicago tribune (Jul 9, 1989), Arts, p. 4. Blois, Marco de. “Lethal weapon II” 24 images 44-45 (autumn 1989), p. 109. Broeske, Pat H. “A high-caliber Danny Glover” Los Angeles times (Jul 11, 1989), Calendar, p. 1. “Business: Talk about placements” Newsweek 114 (Jul 31, 1989), p. 50. Carr, Jay. “Three stooges with guns” Boston globe (Jul 7, 1989), Arts and film, p. 41. Christensen, Johs H. “Dodbringende veben 2” Levende billeder 5 (Sep 1989), p. 47. Clark, Mike. “‘Lethal 2’ is loaded with bang and blanks” USA today (Jul 7, 1989), p. 1D. Cliff, Paul. “Movie trax” Film monthly 1 (Dec 1989), p. -

THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK Screenplay by David Koepp Based on the Novel "The Lost World" by Michael Crichton

THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK Screenplay by David Koepp Based on The Novel "The Lost World" by Michael Crichton PRODUCTION DRAFT August 22, 1996 1 EXT TROPICAL LAGOON DAY A 135 foot luxury yacht is anchored just offshore in a tropical lagoon. The beach is a stunning crescent of sand at the jungle fringe, utterly deserted. ISLA SORNA 87 miles southwest of Nublar Two SHIP HANDS, dressed in white uniforms, have set up a picnic table with three chairs on the sand and are carefully laying out luncheon service - - fine china, silver, crystal descanters with red and white wine. PAUL BOWMAN, fortyish, sits in a chair off to the side, reading. MRS. BOWMAN, painfully thin, with the perpetually surprised look of a woman who’s had her eyes done more than once, supervises the setting of the table. She looks up and sees a little girl, CATHY, seven or eight years old, wandering off down the beach. MRS. BOWMAN Cathy! Don’t wander off! Cathy keeps wandering. MRS. BOWMAN (CONT’D) Come back! You can look for shells right here! Cathy gestures, pretending she can’t hear. BOWMAN (eyes still in his book) Leave her alone. MRS. BOWMAN What about snakes? BOWMAN There’s no snakes on the beach. Let her have fun, for once. 2 FURTHER DOWN THE BEACH, Cathy keeps wandering away, MUTTERING to herself as her parents’ quarreling voices fade in the distance. (CONTINUED) CONTINUED: (2) 2. CATHY Please be quiet, please be quiet, please be quiet . Rounding a curve in the beach, her parents disappear from view behind her. -

CATCH ME IF YOU CAN Written by Jeff Nathanson

CATCH ME IF YOU CAN Written by Jeff Nathanson 1 INT. - GAME SHOW SET. - DAY 1 BLACK AND WHITE FOOTAGE FROM 1978 MUSIC UP: A simple GAME SHOW SET -- one long desk-that houses four "CELEBRITY PANELISTS," a small pulpit with attached microphone for the host, BUD COLLYER, who walks through the curtain to the delight of the audience. Bud bows and waves to the celebrities -- ORSON BEAN, KITTY CARLISLE, TOM POSTON, and PEGGY CASS. BUD COLLYER Hello, panel, and welcome everyone to another exciting day on "To Tell The Truth." Let's get the show started. THE CURTAIN STARTS TO RISE BRIGHT LIGHTS SHINE on the faces of THREE MEN who walk toward center stage. All thre n wear identical AIRLINE PILOT UNIFORMS, each with m; c ng blue blazers and caps. (cont' d) Gentleman, please state your names. PILOT #1 My name is Frank Abagnale Jr. THE PILOT IN THE MIDDLE steps forward. PILOT #2 My name is Frank Abagnale Jr. THE THIRD PILOT does the same. PILOT #3 My name is Frank Abagnale Jr. Bud smiles, grabs a piece of paper. BUD COLLYER Panel, listen to this one. (he starts to read) My name is Frank Abagnale Jr, and some people consider me the worlds greatest imposter. (CONTINUED) Debbie Zane - 2. 1 CONTINUED: 1 As Bud reads, the CAMERA SLOWLY PANS the faces of the three PILOTS. BUD COLLYER (cont'd) (READING) From 1964 to 1966 I successfully impersonated an airline pilot for Pan Am Airlines, and flew over two million miles for free. During that time I was also the Chief Resident Pediatrician at a Georgia hospital, the Assistant Attorney General for the state of Louisiana, and a Professor of American History at a prestigious University in France. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

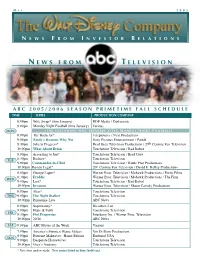

N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N

M A Y 2 0 0 5 N E W S F R O M I N V E S T O R R E L A T I O N S N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N A B C 2 0 0 5 / 2 0 0 6 S E A S O N P R I M E T I M E F A L L S C H E D U L E TIME SERIES PRODUCTION COMPANY 8:00pm Wife Swap* (thru January) RDF Media / Diplomatic 9:00pm Monday Night Football (thru January) Various MON ( T H E F O L L O W I N G W I L L P R E M I E R E A F T E R M O N D A Y N I G H T F O O T B A L L ) 8:00pm The Bachelor* Telepictures / Next Productions 9:00pm Emily’s Reasons Why Not Sony Pictures Entertainment / Pariah 9:30pm Jake in Progress* Brad Grey Television Productions / 20th Century Fox Television 10:00pm What About Brian Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 8:00pm According to Jim* Touchstone Television / Brad Grey 8:30pm Rodney* Touchstone Television TUE 9:00pm Commander-in-Chief Touchstone Television / Battle Plan Productions 10:00pm Boston Legal* 20th Century Fox Television / David E. Kelley Productions 8:00pm George Lopez* Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / Fortis Films 8:30pm Freddie Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / The Firm WED 9:00pm Lost* Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 10:00pm Invasion Warner Bros. -

News Release for Immediate Release

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DISNEY SHOWCASES LIVE ACTION SLATE WITH EXCITING NEWS EXCLUSIVELY FOR FANS AT D23 EXPO 2015 STARS AND FILMMAKERS OF UPCOMING DISNEY, MARVEL STUDIOS AND LUCASFILM MOVIES FEATURED AT TODAY’S LIVE ACTION EVENT Film stills, title treatments and event images will be available at: http://www.image.net/d23_2015. ANAHEIM, Calif. (Aug. 15, 2015) — Disney, Marvel Studios and Lucasfilm presented their live action film slates this morning at the D23 EXPO 2015 at the Anaheim Convention Center in Anaheim, Calif. The presentations, which revealed exclusive news and details about the upcoming live action films, were aided by live and video appearances from talent and filmmakers. Walt Disney Studios Chairman Alan Horn hosted the highly anticipated biennial event. “It’s quite something to be able to have Disney, Marvel and Lucasfilm all on the same stage, and it’s tremendously gratifying to unveil our upcoming projects to our most dedicated fans first,” said Alan Horn, Chairman, The Walt Disney Studios. “We always have an incredible time at the D23 EXPO.” After welcoming the crowd to D23 EXPO 2015, Horn introduced Kevin Feige, President of Marvel Studios, and Sean Bailey, President of Walt Disney Studios Motion Picture Production, to present overviews of the Marvel Studios and Disney live action slates. Later Horn returned to the stage to present the Lucasfilm film slate to the enthusiastic audience. A recap of the presentation follows: · Kevin Feige led off with a glimpse into the world of Marvel’s “Doctor Strange,” featuring a video greeting by Benedict Cumberbatch, who stars as the title character, followed by a pre- production piece that offered fans a taste of the look and feel of the upcoming film, opening in U.S. -

Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului I - 2019 - Straini DACIN SARA

Repartitie aferenta trimestrului I - 2019 - straini DACIN SARA TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Greg Pruss - Gregory Pruss Roland Emmerich - VG Roland Emmerich - VG 2012 2012 2009 US BILD KUNST Harald Kloser BILD KUNST 007: Coordonata Skyfall Skyfall 2012 GB/US Sam Mendes - ALCS Neal Purvis - ALCS Robert Wade - ALCS John Logan - ALCS 007: partea lui de consolare Quantum of Solace 2008 GB/US Marc Forster Neal Purvis - ALCS Robert Wade - ALCS Paul Haggis - ALCS 007: Viitorul e in mainile lui - 007 si Imperiul zilei de maine Tomorrow Never Dies 1997 GB/US Roger Spottiswoode Bruce Feirstein - ALCS Roland Emmerich - VG Roland Emmerich - VG 10 000 HR 10 000 BC 2008 US BILD KUNST Harlad Kloser BILD KUNST 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan Binbir Gece - season 1, episode 1001 de nopti (ep.001) 1 2006 TR Kudret Sabanci - SETEM Yildiz Tunc Murat Lutfu Mehmet Bilal Ethem Yekta Binbir Gece - season 1, episode 1001 de nopti (ep.002) 2 2006 TR Kudret Sabanci - SETEM Yildiz Tunc Murat Lutfu Mehmet Bilal Ethem Yekta Binbir Gece - season 1, episode 1001 de nopti (ep.003) 3 2006 TR Kudret Sabanci - SETEM Yildiz Tunc Murat Lutfu Mehmet Bilal Ethem Yekta Binbir Gece - season 1, episode 1001 de nopti (ep.004) 4 2006 TR Kudret Sabanci - SETEM Yildiz Tunc Murat Lutfu Mehmet Bilal Ethem Yekta Binbir Gece - season 1, episode 1001 de nopti (ep.005) 5 2006 TR Kudret Sabanci - SETEM Yildiz Tunc Murat Lutfu Mehmet Bilal Ethem Yekta -

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: