Electoral Systems in Context: Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transformation of Italian Democracy

Bulletin of Italian Politics Vol. 1, No. 1, 2009, 29-47 The Transformation of Italian Democracy Sergio Fabbrini University of Trento Abstract: The history of post-Second World War Italy may be divided into two distinct periods corresponding to two different modes of democratic functioning. During the period from 1948 to 1993 (commonly referred to as the First Republic), Italy was a consensual democracy; whereas the system (commonly referred to as the Second Republic) that emerged from the dramatic changes brought about by the end of the Cold War functions according to the logic of competitive democracy. The transformation of Italy’s political system has thus been significant. However, there remain important hurdles on the road to a coherent institutionalisation of the competitive model. The article reconstructs the transformation of Italian democracy, highlighting the socio-economic and institutional barriers that continue to obstruct a competitive outcome. Keywords: Italian politics, Models of democracy, Parliamentary government, Party system, Interest groups, Political change. Introduction As a result of the parliamentary elections of 13-14 April 2008, the Italian party system now ranks amongst the least fragmented in Europe. Only four party groups are represented in the Senate and five in the Chamber of Deputies. In comparison, in Spain there are nine party groups in the Congreso de los Diputados and six in the Senado; in France, four in the Assemblée Nationale an d six in the Sénat; and in Germany, six in the Bundestag. Admittedly, as is the case for the United Kingdom, rather fewer parties matter in those democracies in terms of the formation of governments: generally not more than two or three. -

Remaking Italy? Place Configurations and Italian Electoral Politics Under the ‘Second Republic’

Modern Italy Vol. 12, No. 1, February 2007, pp. 17–38 Remaking Italy? Place Configurations and Italian Electoral Politics under the ‘Second Republic’ John Agnew The Italian Second Republic was meant to have led to a bipolar polity with alternation in national government between conservative and progressive blocs. Such a system it has been claimed would undermine the geographical structure of electoral politics that contributed to party system immobilism in the past. However, in this article I argue that dynamic place configurations are central to how the ‘new’ Italian politics is being constructed. The dominant emphasis on either television or the emergence of ‘politics without territory’ has obscured the importance of this geographical restructuring. New dynamic place configurations are apparent particularly in the South which has emerged as a zone of competition between the main party coalitions and a nationally more fragmented geographical pattern of electoral outcomes. These patterns in turn reflect differential trends in support for party positions on governmental centralization and devolution, geographical patterns of local economic development, and the re-emergence of the North–South divide as a focus for ideological and policy differences between parties and social groups across Italy. Introduction One of the high hopes of the early 1990s in Italy was that following the cleansing of the corruption associated with the party regime of the Cold War period, Italy could become a ‘normal country’ in which bipolar politics of electoral competition between clearly defined coalitions formed before elections, rather than perpetual domination by the political centre, would lead to potential alternation of progressive and conservative forces in national political office and would check the systematic corruption of partitocrazia based on the jockeying for government offices (and associated powers) after elections (Gundle & Parker 1996). -

Candidate Ranking Strategies Under Closed List Proportional Representation

The Best at the Top? Candidate Ranking Strategies Under Closed List Proportional Representation Benoit S Y Crutzen Hideo Konishi Erasmus School of Economics Boston College Nicolas Sahuguet HEC Montreal April 21, 2021 Abstract Under closed-list proportional representation, a party’selectoral list determines the order in which legislative seats are allocated to candidates. When candidates differ in their ability, parties face a trade-off between competence and incentives. Ranking candidates in decreasing order of competence ensures that elected politicians are most competent. Yet, party list create incentives for candidates that may push parties not to rank candidates in decreasing competence order. We examine this trade-off in a game- theoretical model in which parties rank their candidate on a list, candidates choose their campaign effort, and the election is a team contest for multiple prizes. We show that the trade-off between competence and incentives depends on candidates’objective and the electoral environment. In particular, parties rank candidates in decreasing order of competence if candidates value enough post-electoral high offi ces or media coverage focuses on candidates at the top of the list. 1 1 Introduction Competent politicians are key for government and democracy to function well. In most democracies, political parties select the candidates who can run for offi ce. Parties’decision on which candidates to let run under their banner is therefore of fundamental importance. When they select candidates, parties have to worry not only about the competence of candidates but also about incentives, about their candidates’motivation to engage with voters and work hard for their party’selectoral success. -

Who Gains from Apparentments Under D'hondt?

CIS Working Paper No 48, 2009 Published by the Center for Comparative and International Studies (ETH Zurich and University of Zurich) Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Dr. Daniel Bochsler University of Zurich Universität Zürich Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Daniel Bochsler post-doctoral research fellow Center for Comparative and International Studies Universität Zürich Seilergraben 53 CH-8001 Zürich Switzerland Centre for the Study of Imperfections in Democracies Central European University Nador utca 9 H-1051 Budapest Hungary [email protected] phone: +41 44 634 50 28 http://www.bochsler.eu Acknowledgements I am in dept to Sebastian Maier, Friedrich Pukelsheim, Peter Leutgäb, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Alex Fischer, who provided very insightful comments on earlier versions of this paper. Manuscript Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Apparentments – or coalitions of several electoral lists – are a widely neglected aspect of the study of proportional electoral systems. This paper proposes a formal model that explains the benefits political parties derive from apparentments, based on their alliance strategies and relative size. In doing so, it reveals that apparentments are most beneficial for highly fractionalised political blocs. However, it also emerges that large parties stand to gain much more from apparentments than small parties do. Because of this, small parties are likely to join in apparentments with other small parties, excluding large parties where possible. These arguments are tested empirically, using a new dataset from the Swiss national parliamentary elections covering a period from 1995 to 2007. Keywords: Electoral systems; apparentments; mechanical effect; PR; D’Hondt. Apparentments, a neglected feature of electoral systems Seat allocation rules in proportional representation (PR) systems have been subject to widespread political debate, and one particularly under-analysed subject in this area is list apparentments. -

A Canadian Model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A

Proportional-first-past-the-post: A Canadian model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador May 2014 ii Abstract For more than a decade a majority of Canadians have consistently supported the idea of proportional representation when asked, yet all attempts at electoral reform thus far have failed. Even though a majority of Canadians support proportional representation, a majority also report they are satisfied with the current electoral system (even indicating support for both in the same survey). The author seeks to reconcile these potentially conflicting desires by designing a uniquely Canadian electoral system that keeps the positive and familiar features of first-past-the- post while creating a proportional election result. The author touches on the theory of representative democracy and its relationship with proportional representation before delving into the mechanics of electoral systems. He surveys some of the major electoral system proposals and options for Canada before finally presenting his made-in-Canada solution that he believes stands a better chance at gaining approval from Canadians than past proposals. iii Acknowledgements First of foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my brilliant supervisor, Dr. Amanda Bittner, whose continuous guidance, support, and advice over the past few years has been invaluable. I am especially grateful to you for encouraging me to pursue my Master’s and write about my electoral system idea. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Civitas - Revista de Ciências Sociais ISSN: 1519-6089 ISSN: 1984-7289 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul Vannucci, Alberto Systemic corruption and disorganized anticorruption in Italy: governance, politicization, and electoral accountability Civitas - Revista de Ciências Sociais, vol. 20, no. 3, 2020, September-December, pp. 408-424 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul DOI: https://doi.org/10.15448/1984-7289.2020.3.37877 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=74266204008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative OPEN ACCESS CIVITAS Revista de Ciências Sociais Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Sociais Civitas 20 (3): 408-424, set.-dez. 2020 e-ISSN: 1984-7289 ISSN-L: 1519-6089 http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1984-7289.2020.3.37877 DOSSIER: FIGHT AGAINST CORRUPTION: STATE OF THE ART AND ANALYSIS PERSPECTIVES Systemic corruption and disorganized anticorruption in Italy: governance, politicization, and electoral accountability Corrupção sistêmica e anticorrupção desorganizada na Itália: governança, politização e accountability eleitoral Corrupción sistémica y anticorrupción desorganizada en Italia: gobernanza, politización y accountability electoral Alberto Vannucci1 Abstract: This paper provides, trough different indicators, empirical evidence on the orcid.org/0000-0003-0434-1323 presumably high relevance of corruption in Italian politics and administration, providing [email protected] an explanation of how this “obscure” side of Italian politics – a pervasive market for corrupt exchanges – has found its way to regulate its hidden activities within an informal institutional framework, i.e. -

ITA Parliamentary 2013

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights THE ITALIAN REPUBLIC EARLY PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 24 and 25 February 2013 OSCE/ODIHR NEEDS ASSESSMENT MISSION REPORT 7-10 January 2013 Warsaw 22 January 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 1 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... 1 III. FINDINGS .............................................................................................................................................. 3 A. BACKGROUND AND POLITICAL CONTEXT ............................................................................................. 3 B. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................................................. 3 C. ELECTORAL SYSTEM ............................................................................................................................. 4 D. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION ................................................................................................................. 5 E. VOTING METHODS ................................................................................................................................ 6 F. VOTER RIGHTS AND REGISTRATION ...................................................................................................... 7 G. CANDIDATE RIGHTS AND REGISTRATION -

The Persistence of Corruption in Italy

The Persistence of Corruption in Italy: Politicians and the Judiciary since Mani Pulite Raffaele Asquer Department of Political Science University of California, Los Angeles Paper prepared for the WPSA 2013 ANNUAL MEETING March 28th, 2013 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR CIRCULATE 1 Abstract Starting in 1992, the Mani Pulite (“Clean Hands”) anti-corruption campaign promised to eradicate corruption from Italian political life. For a brief, yet intense period, the public rallied behind the prosecutors, and punished the allegedly corrupt politicians and parties at the polls. However, twenty years later, Italy is still ranked as highly corrupt by Western standards. Why, then, did the Mani Pulite campaign fail to have a long-lasting effect? Relying on original data on the anti-corruption investigations in Milan, as well as on a variety of datasources from the existing literature, this paper argues, first, that the investigations left essentially untouched entire parts of the country where corruption was widespread. Overall, the Mani Pulite campaign had limited deterring effects because judicial inquiries were obstructed by the statute of limitations, and even in case of conviction the sentences were generally mild. Second, the paper finds that the structures of corruption networks have changed since the Mani Pulite season, becoming less vulnerable to further judicial inquiries. There now seem to be multiple sites for corrupt transactions, somewhat dispersed throughout the political system, whereas in the past such activities were centrally managed by a cartel of parties. We reach this conclusion by combining evidence from the literature with original data on two subnational legislatures, the Regional Council of Campania (1992-94) and the Regional Council of Lombardy (2010-12) in which political malfeasance in general seemed widespread. -

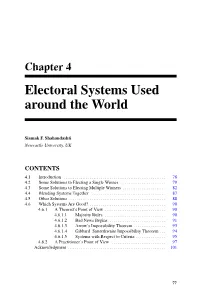

Electoral Systems Used Around the World

Chapter 4 Electoral Systems Used around the World Siamak F. Shahandashti Newcastle University, UK CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 78 4.2 Some Solutions to Electing a Single Winner :::::::::::::::::::::::: 79 4.3 Some Solutions to Electing Multiple Winners ::::::::::::::::::::::: 82 4.4 Blending Systems Together :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 87 4.5 Other Solutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 88 4.6 Which Systems Are Good? ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1 A Theorist’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.1 Majority Rules ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.2 Bad News Begins :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 91 4.6.1.3 Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem ::::::::::::::::: 93 4.6.1.4 Gibbard–Satterthwaite Impossibility Theorem ::: 94 4.6.1.5 Systems with Respect to Criteria :::::::::::::::: 95 4.6.2 A Practitioner’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 97 Acknowledgment ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 101 77 78 Real-World Electronic Voting: Design, Analysis and Deployment 4.1 Introduction An electoral system, or simply a voting method, defines the rules by which the choices or preferences of voters are collected, tallied, aggregated and collectively interpreted to obtain the results of an election [249, 489]. There are many electoral systems. A voter may be allowed to vote for one or multiple candidates, one or multiple predefined lists of candidates, or state their pref- erence among candidates or predefined lists of candidates. Accordingly, tallying may involve a simple count of the number of votes for each candidate or list, or a relatively more complex procedure of multiple rounds of counting and transferring ballots be- tween candidates or lists. Eventually, the outcome of the tallying and aggregation procedures is interpreted to determine which candidate wins which seat. Designing end-to-end verifiable e-voting schemes is challenging. -

Appendix A: Electoral Rules

Appendix A: Electoral Rules Table A.1 Electoral Rules for Italy’s Lower House, 1948–present Time Period 1948–1993 1993–2005 2005–present Plurality PR with seat Valle d’Aosta “Overseas” Tier PR Tier bonus national tier SMD Constituencies No. of seats / 6301 / 32 475/475 155/26 617/1 1/1 12/4 districts Election rule PR2 Plurality PR3 PR with seat Plurality PR (FPTP) bonus4 (FPTP) District Size 1–54 1 1–11 617 1 1–6 (mean = 20) (mean = 6) (mean = 4) Note that the acronym FPTP refers to First Past the Post plurality electoral system. 1The number of seats became 630 after the 1962 constitutional reform. Note the period of office is always 5 years or less if the parliament is dissolved. 2Imperiali quota and LR; preferential vote; threshold: one quota and 300,000 votes at national level. 3Hare Quota and LR; closed list; threshold: 4% of valid votes at national level. 4Hare Quota and LR; closed list; thresholds: 4% for lists running independently; 10% for coalitions; 2% for lists joining a pre-electoral coalition, except for the best loser. Ballot structure • Under the PR system (1948–1993), each voter cast one vote for a party list and could express a variable number of preferential votes among candidates of that list. • Under the MMM system (1993–2005), each voter received two separate ballots (the plurality ballot and the PR one) and cast two votes: one for an individual candidate in a single-member district; one for a party in a multi-member PR district. • Under the PR-with-seat-bonus system (2005–present), each voter cast one vote for a party list. -

Tecniche Normative

tecniche normative Lara Trucco The European Elections in Italy* SUMMARY: 1. The main features of the Italian electoral system for the EU Parliament election. – 2. The electoral campaigns for the EP election. – 3. From Europe towards the Italian results. – 4. The regional effects of the results of the EU elections. – 5. The crises of the “Yellow-Green” Government. 1. The main features of the Italian electoral system for the EU Parliament election In Italy, the elections of the members of the European Parliament were held on the 26th May 2019. Firstly, the decision of the European Council no. 937 of 2018 should be considered. According to this, 76 seats of the EP were allocated to Italy starting from the 2019 legislature (as we know, the MEPs are 751). However, as specified by the Court of Cassation on the 21st May 2019, of these 76 European parliamentarians assigned to Italy, only 73 will take over immediately, while the remaining 3 seats will be given only after the UK has effectively left the EU. This means that if the UK does not leave the EU, Italy will have 73 seats for the entire Legislature. We voted with the electoral system established by law no. 18 of 1979 (law about the “Election of the Italian members of the European Parliament”). The right to vote is exercised by citizens at least 18 years old, while for candidates, the minimum age is 25 years. Let’s look in more detail: 1) The electoral districts The Italian national territory is divided into 5 plurinominal districts, in which the seats are allocated in proportion to the population. -

Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls

Alan Wall and Mohamed Salih Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 1 Indonesia – Voting Station 2005 Index 1 Introduction 5 2 Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 6 2.1 What Is Electoral Engineering? 6 2.2 Basic Terms and Classifications 6 2.3 What Are the Potential Objectives of an Electoral System? 8 3 2.4 What Is the Best Electoral System? 8 2.5 Specific Issues in Split or Post Conflict Societies 10 2.6 The Post Colonial Blues 10 2.7 What Is an Appropriate Electoral System Development or Reform Process? 11 2.8 Stakeholders in Electoral System Reform 13 2.9 Some Key Issues for Political Parties 16 3 Further Reading 18 4 About the Authors 19 5 About NIMD 20 Annex Electoral Systems in NIMD Partner Countries 21 Colophon 24 4 Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 1 Introduction 5 The choice of electoral system is one of the most important decisions that any political party can be involved in. Supporting or choosing an inappropriate system may not only affect the level of representation a party achieves, but may threaten the very existence of the party. But which factors need to be considered in determining an appropriate electoral system? This publication provides an introduction to the different electoral systems which exist around the world, some brief case studies of recent electoral system reforms, and some practical tips to those political parties involved in development or reform of electoral systems. Each electoral system is based on specific values, and while each has some generic advantages and disadvantages, these may not occur consistently in different social and political environments.