The Long Island Railroad Milk Car Mystery SOLVED WALTER WOHLEKING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

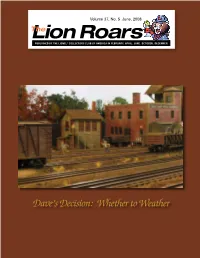

Dave's Decision: Whether to Weather

Volume 37, No. 5 June, 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE LIONEL® COLLECTORS CLUB OF AMERICA IN FEBRUARY, APRIL, JUNE, OCTOBER, DECEMBER Dave’s Decision: Whether to Weather The Lion Roars June, 2008 LAST CHANCE TO ORDER Deadline Imminent The Lionel Collectors Club of America offers these two This limited-edition production run will include these quality distinctive cars of the northeast region — “Susie Q” and Ontario features: Northland RR — to members as the 2008 Convention car. Limit: • produced by Lionel® exclusively for LCCA two sets per member. • die-cast, fully sprung trucks with rotating roller bearing caps; truck sideframes are painted to match the cars The Susquehanna car will include the classic rendering of the • roof hatches actually open and close “Susie Q” character never before presented on a hopper car. This • crisp graphics with SUSIE Q and ONR décor pair will appeal to Susie Q and Canadian model railroaders, niche • added-on (not molded-in) ladders and brake wheels collectors seeking rolling stock of northeastern regional railroads, • detailed undercarriage and collectors of LCCA Convention cars. • discrete LCCA 2008 Convention designation on the underside. Order Form for “Susie Q” and ONR Cars Once submitted, LCCA will consider this a firm, non-refundable order. Deadline for ordering: June 30, 2008. Note: UPS cannot deliver to a post office box. A street address is required. Name: ____________________________________________________________________ LCCA No.: ________________ Address: ____________________________________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________________________________________________ State: ____ Zip + 4: __________________ Phone: (______) ______________________ e-mail: __________________________________________________________ [ ] Check this box if any part of your address is new. Do the Math: [ ] Payment Plan A: My check for the full amount is enclosed made payable to 2008 LCCA Convention Car “LCCA” with “TLR/2008CC” written on the memo line. -

Toy Train Auction 10:00 A.M

TOY TRAIN AUCTION 10:00 A.M. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2015 EXHIBITION 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. Friday and from 8 a.m. to 10 a.m. Saturday The exhibition will close at 10 a.m. when the sale commences. RIDGE FIRE COMPANY PAVILION 480 RIDGE ROAD (Along Rt. 23, Between Phoenixville, PA and Rt. 100) SPRING CITY, PA 19475 A few select pictures for this auction may be viewed on auctionzip.com #1892. MAURER'S AUCTIONS SUCCESSFUL AUCTION MANAGEMENT 1408 CHESTNUT STREET POTTSTOWN, PA 19464 610-970-7588 ALSO PREVIEW & AUCTION DAY AT 610-495-5504 WWW.MAURERAIL.COM Auctionzip.com #1892 6% PA SALES TAX 12% BUYER'S PREMIUM, 2% DISCOUNT FOR CASH OR CHECK DEALERS: WE NEED A COPY OF YOUR TAX ID CERTIFICATION FOR OUR FILES. LOTS 1 THRU 17 ARE LIONEL PREWAR 31. 2333 SF AA Diesels, OB & Master Carton Picture 1. Set 134: 252 Orange Loco w/Two 603, 604 Orange/Terra 32. 2460 Twelve-Whl. Crane, 3451 Opr. Lumber Car, OB Cotta Pass. Cars, Tattered OB & Good Set Box Picture 33. 3459 Green, 2411, 2458, 2357 Frts., 3 OB & 1 Repro. Box 2. Set 294E: 249E, 265T GM /Two 67, 608 TT Green Pass. 34. 671W Loco w/2671W Tender, RB Cars, OB & Set Box Picture 35. 2400, 01, 02 Green/Gray Pass. Cars, Tatt. OB Picture 3. Set 7003: 1688, 1689T Black L&T w/1679, 1680, 1682 36. 2023 UP Anniv. Colors Alco AA Diesels, OB Picture Frts., Instr., OB & Set Box Picture 37. 2481, 82, 83 Anniv. Colors Pass. -

Train Cars and Accessories.Pdf

Manufacturer Model No. Description Price Photos Lionel ZW Transformer $300.00 (Professionally rebuilt and never used after being serviced) Lionel ZW Transformer $300.00 (Professionally rebuilt and never used after being serviced) Lionel 14077 ZW Amp/Volt $249.00 Meter Page 1 of 34 K-Line K6243- U.P. 3-Bay $124.00 2111 Modern Hopper K-Line K613-2113 U.P "Survivor" $86.99 Scale Extended Vision Caboose K-Line K623- U.P. Die-Cast $159.00 2112A Hopper Car Three (3) Pack K-Line K6243- U.P. Aluminum 3 $124.00 2112 Bay Center Floor Modern Hopper – Cab. No. 21505 K-Line K6332- CSX Scale Bay $55.00 1431 Window Caboose K-Line K6333- U.P. Aluminum $55.00 2111 Tank Car Page 2 of 34 K-Line K6333- U.P. Aluminum $189.00 2112A Tank Car Three (3) Pack L-Line K652-2171 Western Pacific $55.00 Gondola K-Line K676- ATSF Classic $92.00 1051A Coil Car w/Coal Load Three (3) Pack K-Line K691-1052 ATSF Die Cast $55.00 Boxcar K-Line K752-2112 U.P. Pacific Fruit $55.00 Express Die-Cast Reefer K-Line K761- U.P. Boxcar $171.00 2111A Three (3) Pack Page 3 of 34 K-LINE L761-9013 K-Line $55.00 Superstore Box Car Page 4 of 34 K-Line K774-1431 CSX Trailer Two $72.00 (2) Pack K-Line K776502 Southern Pacific $54.00 Gunderson DTTX w/Trailer Page 5 of 34 K-Line K691-1051 ATSF Scale $44.00 Classis Flat Car w/3 die cast Chevy Camaros Page 6 of 34 Lionel 17110 U.P. -

NASG S Scale Magazine Index PDF Report

NASG S Scale Magazine Index PDF Report Bldg Article Title Author(s) Scale Page Mgazine Vol Iss Month Yea Dwg Plans "1935 Ridgeway B6" - A Fantasy Crawler in 1:24 Scale Bill Borgen 80 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 2004 "50th Anniversary of S" - 1987 NASG Convention Observations Bob Jackson S 6 Dispatch Dec 1987 "Almost Painless" Cedar Shingles Charles Goodrich 72 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 1994 "Baby Gauge" in the West - An Album of 20-Inch Railroads Mallory Hope Ferrell 47 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Jul - Aug 1998 "Bashing" a Bachmann On30 Gondola into a Quincy & Torch Lake Rock Car Gary Bothe On30 67 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Jul - Aug 2014 "Been There - Done That" (The Personal Journey of Building a Model Railroad) Lex A. Parker On3 26 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 1996 "Boomer" CRS Trust "E" (D&RG) Narrow Gauge Stock Car #5323 -Drawings Robert Stears 50 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz May - Jun 2019 "Brakeman Bill" used AF trains on show C. C. Hutchinson S 35 S Gaugian Sep - Oct 1987 "Cast-Based" Rock Work Phil Hodges 34 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Nov - Dec 1991 "Causey's Coach" Mallory Hope Ferrell 53 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Sep - Oct 2013 "Chama," The PBL Display Layout Bill Peter, Dick Karnes S 26 3/16 'S'cale Railroading 2 1 Oct 1990 "Channel Lock" Bench Work Ty G. Treterlaar 59 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Mar - Apr 2001 "Clinic in a Bag" S 24 S Gaugian Jan - Feb 1996 "Creating" D&RGW C-19 #341 in On3 - Some Tips Glenn Farley On3 20 Narrow Gauge & Short Line Gaz Jan - Feb 2010 "Dirting-In" -

The National Model Railroad Association, Inc

Spring Meet Issue Official Publication of the Northeastern Region SUNRISE TRAIL DIVISION National Model Railroad Association VOLUME 40 ISSUE 1 SPRING 2010 A Big Hello to all our Cannonball readers, and welcome to in Burlington Vermont. Close to home, in April, look forward the first Issue of the year. I hope you're making plans to take to the Sunrise Trail Division's Spring Meet and to the Sunrise advantage of one or more of the NMRA sponsored Conventions Trail Division's Fall Convention in November. this year. Take a look inside for information on some of these Also in this issue you'll find information on an NMRA / UP conventions; first is this years Maritime Federation of Model Photo Contest, the Sunrise Trail Division's 2009 Fall Conven- Railroaders & NMRA Northeastern Region Joint Convention tion Contest Results, Long Island Rail Road Milk Car research "Tides & Trains" Convention in May. This summer, celebrat- results, a Sunrise Trail Division Members’ layout story, a ques- ing the 75th Anniversary of the NMRA, the National Conven- tion from your editor, some pictures of hirail equipment, and an tion will be held in Milwaukee, WI. In September the NMRA article on having fun with model photography. Northeastern Region Convention, The Champlain Flyer, will be Enjoy! *********************************************** SPRING MODEL RAILROAD MEET **************** April 10, 2010*************** Sponsored by SUNRISE TRAIL DIVISION Northeastern Region, NMRA St. David's Lutheran Church z 20 Clark Boulevard z Massapequa Park z 10 AM to 4 PM • Installation of Officers for 2010 • Live Clinics • Model Contest (NMRA Merit Award Judging) • Photo Contest • White Elephant Table • Modular Layouts On Display • REFRESHMENTS (For Sale) ADMISSION: $3.00 non-members z $2.00 NMRA members SPRING 2010 1 of those impressive layouts shown in the model railroading press are old guys (apologies to other old guys — I’m one commentary / WALTER WOHLEKING myself). -

Lot Description 1001 Lionel O Gauge 2657 Caboose 1002 Lionel O

lot Description 1001 Lionel O Gauge 2657 Caboose 1002 Lionel O Gauge 2655 Boxcar, Missing 1 Door 1003 Lionel O Gauge 2654 Sunoco Tank Car, Some Rust 1004 9"T x 15L" Wooden Semi Dupont, Trailer wheels Turn, Truck wheels do not 1005 Ertl NorthLand Kenworth T600A 1/64 1006 Lionel O Gauge 3454 PRR Automatic Merchandise Car 1007 Lionel O Gauge 2420 D.L.&W. Work Caboose w/ Search light 1008 6414 Evans Auto Loader Lionel O Gauge, No Autos 1008A Case IH 135 Maxxum 1/16 1009 Winchester 1975 IH R-190 Truck Bank 1/34 1010 Ertl 7up 1955 Chevy Pickup Bank 1011 PRR 347000, 2454 Gondola, missing 1 brake wheel 1012 NYC 6562 Gondola Lionel O Gauge 1013 Lionel O Gauge 6017 Caboose 1014 Lionel O Gauge 6167 Caboose 1015 3509 Satellite Launching Car, Missing Sat. & Radar Dish 1016 MF 1190 Laf Toy Show Resin 1/32 1017 MF 4800 4WD 1/32 1018 Lionel Southern 8956 Non-Powered Dummy Engine 1019 Lionel MKT 600 Switcher 1020 Lionel Santa Fe 8352 GP-20 Engine 1021 Case 1690 cab 1/32 1022 Case 1690 no cab 1/32 1023 Case Folding Disc 1/32 1024 Lionel 3462 Operating Ref. Milk Car & Platform, Milk Cans 1025 Lionel 63132 AT&SF Operating Box Car 1026 Lionel 3665 Minuteman Missle Launch Car, No Missle 1027 IH 4 Bottom Trailing Plow 1/16 1028 Ertl Red 3pt Die Cast Blade 1/16 1029 (2) Lionel 210 The Texas Special Engines o/27 Gauge 1030 Lionel 2023 Union Pacific Engine o/27 Gauge 1031 Lionel 2023 Union Pacific Engine o/27 Gauge 1032 JD 430 Crawler 1/16 1033 JD 430 Crawler 1/16 1034 JD Plastic 430 Crawler 1/16 1035 Lionel 2654 Sunoco Tank Car 1036 Lionel 657 Caboose 1037 Lionel 2657 Caboose 1037A Ertl Red Disc 1/16 1038 Mayfield Ice Cream Jersey Flange 20"x18" 1039 Lynks Seeds Dealer Sign 27"x18" 1040 Lionel 2555 Sunoco metal Tank Car 1041 Lionel 2555 Sunoco metal Tank Car 1042 Allis Chalmers One-Ninety 1/16 1043 Allis Chalmer 175 "Crop Hustler" 1/16 1044 MF 1155 Spirt of America 1/16 1045 Lionel Penn 477618 Eastern div. -

Strategic List Services 888-848-1215 8 Digit SIC Codes

Strategic List Services 8 Digit SIC Codes 1 of 276 888-848-1215 (Standard Industry Codes) SIC DESCRIPTION 1110000 WHEAT 1120000 RICE 1150000 CORN 1160000 SOYBEANS 1190000 CASH GRAINS, NEC 1190100 PEA AND BEAN FARMS (LEGUMES) 1190101 BEAN (DRY FIELD AND SEED) FARM 1190102 COWPEA FARM 1190103 LENTIL FARM 1190104 MUSTARD SEED FARM 1190105 PEA (DRY FIELD AND SEED) FARM 1190200 FEEDER GRAINS 1190201 EMMER FARM 1190202 MILO FARM 1190203 OAT FARM 1190300 OIL GRAINS 1190301 FLAXSEED FARM 1190302 SAFFLOWER FARM 1190303 SUNFLOWER FARM 1190400 CEREAL CROP FARMS 1190401 BARLEY FARM 1190402 BUCKWHEAT FARM 1190403 RYE FARM 1190404 SORGHUM FARM 1199901 POPCORN FARM 1310000 COTTON 1319901 COTTONSEED FARM 1320000 TOBACCO 1330000 SUGARCANE AND SUGAR BEETS 1339901 SUGAR BEET FARM 1339902 SUGARCANE FARM 1340000 IRISH POTATOES 1390000 FIELD CROPS, EXCEPT CASH GRAIN 1390100 FEEDER CROPS 1390101 ALFALFA FARM 1390102 CLOVER FARM 1390103 GRASS SEED FARM 1390104 HAY FARM 1390105 TIMOTHY FARM 1390200 FOOD CROPS 1390201 PEANUT FARM 1390202 SWEET POTATO FARM 1399901 BROOMCORN FARM 1399902 FLAX FARM 1399903 HOP FARM 1399904 MINT FARM 1399905 HERB OR SPICE FARM 1610000 VEGETABLES AND MELONS 1610100 MELON FARMS 1610101 CANTALOUPE FARM 1610102 CRENSHAW MELON FARM 1610103 HONEYDEW MELON FARM 1610104 WATERMELON FARM 1610200 PEA AND BEAN FARMS 1610201 ENGLISH PEA FARM 1610202 LIMA BEAN FARM, GREEN 1 Strategic List Services 8 Digit SIC Codes 2 of 276 888-848-1215 (Standard Industry Codes) 1610203 PEA FARM, GREEN (EXCEPT DRY PEAS) 1610204 SNAP BEAN FARM (BUSH AND POLE) 1610300 -

Reviews with Bob Keller and the CTT Staff

reviews With Bob Keller and the CTT Staff Product reviews in Classic Toy Trains magazine Inclusive from Fall 1987 through December 2010 issue Manufacturer Issue Product and reviewer 3rd Rail Jan 94 O gauge brass Pennsylvania RR S2 6-8-6 Turbine by 3rd Rail – Dick Christianson 3rd Rail May 94 O gauge brass Pennsylvania RR 2-10-0 by 3rd Rail – Tom Rollo 3rd Rail Jan 96 Update on review of O gauge S2 6-8-6 Turbine by 3rd Rail – Marty McGuirk 3rd Rail May 96 O gauge brass Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 Big Boy by 3rd Rail – Marty McGuirk 3rd Rail Sep 97 O gauge brass Union Pacific 4-6-6-4 Challenger by 3rd Rail – Bob Keller 3rd Rail Jan 98 O gauge brass Pennsylvania RR 2-10-4 by 3rd Rail – Bob Keller 3rd Rail Nov 98 O gauge brass Pennsylvania RR Q2 4-4-6-4 by 3rd Rail – Bob Keller 3rd Rail Jan 99 O gauge Santa Fe Dash 8 by 3rd Rail – Bob Keller 3rd Rail Mar 99 O gauge Southern Pacific 4-8-8-2 cab-forward by 3rd Rail – Bob Keller 3rd Rail Nov 99 O gauge Pennsylvania RR S1 6-4-4-6 by 3rd Rail – Bob Keller 3rd Rail Sep 00 CTT Online review: Pennsylvania RR 2-10-2 – Bob Keller 3rd Rail Jul 01 O gauge brass UP & SP 2-8-0s by 3rd Rail – Bob Keller 3rd Rail Jan 02 O gauge brass Erie 0-8-8-0 by 3rd Rail – Bob Keller 3rd Rail Jul 02 O gauge brass Union Pacific 4-6-6-4 Challenger by 3rd Rail – Bob Keller 3rd Rail Oct 02 O gauge die-cast metal NYC Mercury 4-6-2 Pacific by 3rd Rail – Bob Keller 3rd Rail Nov 02 O gauge brass NYC 4-8-4 Northern by 3rd Rail – Bob Keller 3rd Rail May 04 O gauge brass Pennsylvania RR Q1 4-6-4-4 locomotives – Bob Keller 3rd Rail July 08 O gauge brass C&O 4-8-4 by Third Rail – Bob Keller Academy Models Dec 02 1:48 scale tanks by Academy Models – Bob Keller Ace Trains Sep 00 O gauge 4-4-4T and car set by Ace Trains – Neil Besougloff Ace Trains Jan 01 Southern (UK) Ry. -

S & W Parts Supply 762 Whitney Drive Niskayuna, NY 12309-3018 Parts List X-XXXXX [email protected] (

S & W Parts Supply Parts List [email protected] 762 Whitney Drive www.SandWparts.com Niskayuna, NY 12309-3018 X-XXXXX (518) 280-5197 Stock Number Item Description Price 6-11020 Hogwart's Express $ 299.95 6-11038 Snow/4 Pak Str Trk $ 15.00 6-11067 Lionel Bear $ 24.95 6-11253 NH #3603 0-8-0 Swtch $ 699.99 6-11341 4-12-2 Pilot Loco $ 1,299.95 6-11386 B&M Berkshire/Legacy $ 1,249.99 6-11387 S.F. Berkshire L/T $ 728.74 6-11389 B & A Berkshire $ 1,249.99 6-11715 90TH Ann.Set $ 560.00 6-11734S Erie FF Set $ 725.00 6-11737 TCA ABA F-3 Set $ 600.00 6-11809 Village Trolley Set $ 99.95 6-11844 U.P. Cast Ore Cars/4 $ 265.00 6-11853 B & M PS-2 Hopper $ 95.00 6-11866 Govt. Can. Hopper $ 100.00 6-11912 SS.Exclusive/96 NY82 $ 325.00 6-11993 Cat./1993 Book I $ 2.00 6-12014 Straight Track $ 4.79 6-12019 90 Degree Crossover $ 20.00 6-12023 1/4 Curve Track $ 4.59 6-12033 O-36 Full Curve/Blk $ 4.00 6-12036 Grade Crossing $ 12.75 6-12037 Graduated Trestle $ 74.99 6-12038 Elevated Trestle $ 39.99 6-12040 Transition Track/Fst $ 9.99 6-12041 0-72 Curve $ 6.00 6-12051 45'Crossing/Fastrack $ 27.99 6-12059 Earthen Bumper $ 11.99 6-12062 Grade Crsing W/Gates $ 159.99 6-12180 Sign Set $ 3.00 6-12700 Erie Magnetic Crane $ 225.00 6-12707 Billboards $ 7.95 6-12709 Banjo Signal $ 44.95 6-12715 Bumpers/Lighted $ 12.99 6-12717 Non Ill Bumpers Ny76 $ 7.49 6-12719 Refreshment Stand $ 75.00 6-12722 Road Side Diner $ 53.00 6-12728 Ill.Pass.& Frt.Stat. -

2020 Lionel Catalog Pre-Order Program & Price List

2020 Lionel Catalog Pre-Order Program & Price List PRE-ORDER DEADLINE FEBRUARY 29, 2020 Item Cat Pre-Order Suggested Expect Qty Description Number Page # Price Retail Due CELEBRATING 120 YEARS OF LIONEL 2031400 BTO Lionel Lines VISION GS-4 #120 6-7 $1,799.99 $1,999.99 4th QTR 2026910 NEW Lionel 120 Northeast Caboose 6-7 $86.29 $114.99 3rd QTR 2027630 NEW Lionel Lines VistaVision Dome CHESTERFIELD 6-7 $254.99 $339.99 3rd QTR 2027690 NEW Lionel Lines VISION Baggage Car MADISON 6-7 $262.49 $349.99 3rd QTR 2027750 NEW Lionel Lines 120 21" Passenger 4 Pack 6-7 $547.49 $729.99 3rd QTR 2027760 NEW Lionel Lines StationSounds Diner MOUNT CLEMENS 6-7 $254.99 $339.99 3rd QTR 2022120 BTO Lionel 120th Deluxe LionChief Plus 2.0 F3 Set 8-9 $899.99 $999.99 4th QTR 2029010 NEW 85th Anniversary Gateman 8-9 $82.49 $109.99 3rd QTR 2029270 NEW Lionelville Freight Station 8-9 $93.74 $124.99 3rd QTR 2035050 NEW Lionelville Trolley 8-9 $74.99 $99.99 3rd QTR 2023120 NEW Lionel Lines LionChief® Set 10-11 $239.99 $299.99 3rd QTR 2028310 NEW Best of Lionel - Lionel Milk Car 10-11 $139.99 $179.99 3rd QTR 2028480 NEW Best of Lionel - Angela Trotta Thomas 120th Boxcar 10-11 $56.29 $74.99 3rd QTR VISIONLINE GS-1 HYBRID 2031411 BTO Southern Pacific #4470 16-17 $2,199.99 $2,199.99 4th QTR 2031412 BTO Southern Pacific #4471 16-17 $2,199.99 $2,199.99 4th QTR 2031421 BTO Southern Pacific #708 16-17 $2,199.99 $2,199.99 4th QTR 2031422 BTO Southern Pacific #4403 16-17 $2,199.99 $2,199.99 4th QTR 2031430 BTO Pilot #9999 16-17 $2,199.99 $2,199.99 4th QTR VISION GS-2 2031440 BTO -

Models B&MRR HO-Scale Freight Cars

Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Incorporated File 16. B&M.RR. B&L.RR. CP.RR. Fitchburg RR. MEC.RR. NH.RR. CV.RR. HO-Scale Freight Cars, Hardware Collection Boston & Maine Freight Paint Schemes • In the 1920’s, the B&M standard was the wood sided cars (which apparently included the 1929 steel boxcars) were boxcar red. Hoppers, Gondolas and Flatcars were black, although it is not clear how this was applied to the USRA composite gondolas. Either way, lettering was white. The reporting marks were B&M. • Several variations on heralds were applied at different times. The earliest was a white rectangle with the road name in the white on a black background and a red upwards- facing arrow through the “B” and “AND”. This was used on the USRA double-sheathed cars delivered in 1919. Later a multi-color “map” herald with “Minute Man Service” lettered underneath was tried on a few years. • The 1929/30 boxes and hoppers had a simpler rectangular herald with the same “Minute Man Service” slogan. • After the 1938 change to “BM” reporting marks, the B&M only used two heralds on Hoppers, Gondolas and House cars: The earlier was the simple rectangle containing the road name, with out the slogan. Boston & Lowell Railroad 1880’s Wood Box Cars 36’ Truss Rod Wood Box Cars Boston & Lowell Railroad 36’ Wood Truss-rod Box Car #583 Color: Boxcar red / white lettering. Boston & Lowell Railroad 36’ Wood Truss-rod Box Car #586 Color: Boxcar red / white lettering. B&MRRHS Collection Fitchburg Railroad 36’ Wood Truss Rod Box Cars Fitchburg Railroad 36’ Wood Truss-rod Box Car #8459 Hoosac Tunnel Route Color: Boxcar red / white lettering Fitchburg Railroad 36’ Wood Truss-rod Box Car #3243 Hay Car Color: Boxcar red / white lettering B&MRRHS Collection Boston & Maine Railroad 36’ Wood Truss Rod Box Cars Boston & Maine Railroad 36’ Wood Truss-rod Box Car #12000 Machinery Color: Boxcar red / white lettering. -

Nycentral Modeler

4th Quarter 2019 Volume 9 Number 4 Table of Contents On the Cover of This Issue Custom Rolling Stock Honors Nickel City’s Past by Bob Shaw 32 Finally Modeling the Putman Division by Howie Mann 39 NYC’s Former MC&CS Waycars Part 1 by Seth Lakin Seth Lakin begins a two-part series on NYC’s 45 former MC&CS waycars in this issue. Page 45 Building a Sunshine Models Express Reefer by Bob Chapman NYCSHS Members Models 62 NYCSHS Gift to the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania by Noel Widdifield 71 St. Louis RPM Meet By Dennis Regan 75 From the Cab 5 Extra Board 8 What’s New 12 Stan Madyda modeled a NYC flatcar loaded with NYCSHS RPO 21 Farmall tractors and shared a photo of the finished NYCSHS Models 81 Observation Car 84 model. Page 81 NYCentral Modeler The NYCentral Modeler focuses on providing information about modeling of the railroad in all scales. This issue features articles, photos, and reviews of NYC-related models and layouts. The objective of the publication is to help members improve their ability to model the New York Central and promote modeling interests. Contact us about doing an article for us. mailto:[email protected] NYCentral Modeler 4th Quarter 2019 2 New York Central System Historical Society The New York Central System Central Headlight, the official Historical Society (NYCSHS) was publication of the NYCSHS. The organized in March 1970 by the Central Headlight is only available combined efforts of several to members, and each issue former employees of the New contains a wealth of information Board of Directors Nick Ariemma, J.