Read the Introduction (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities In

“Go eat a bat, Chang!”: On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the Face of COVID-19 Fatemeh Tahmasbi Leonard Schild Chen Ling Binghamton University CISPA Boston University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jeremy Blackburn Gianluca Stringhini Yang Zhang Binghamton University Boston University CISPA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Savvas Zannettou Max Planck Institute for Informatics [email protected] ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives in COVID-19, Sinophobia, Hate Speech, Twitter, 4chan unprecedented ways. In the face of the projected catastrophic conse- ACM Reference Format: quences, most countries have enacted social distancing measures in Fatemeh Tahmasbi, Leonard Schild, Chen Ling, Jeremy Blackburn, Gianluca an attempt to limit the spread of the virus. Under these conditions, Stringhini, Yang Zhang, and Savvas Zannettou. 2021. “Go eat a bat, Chang!”: the Web has become an indispensable medium for information ac- On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the quisition, communication, and entertainment. At the same time, Face of COVID-19. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021 (WWW ’21), unfortunately, the Web is being exploited for the dissemination April 19–23, 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 12 pages. of potentially harmful and disturbing content, such as the spread https://doi.org/10.1145/3442381.3450024 of conspiracy theories and hateful speech towards specific ethnic groups, in particular towards Chinese people and people of Asian 1 INTRODUCTION descent since COVID-19 is believed to have originated from China. -

The Chinese in Hawaii: an Annotated Bibliography

The Chinese in Hawaii AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY by NANCY FOON YOUNG Social Science Research Institute University of Hawaii Hawaii Series No. 4 THE CHINESE IN HAWAII HAWAII SERIES No. 4 Other publications in the HAWAII SERIES No. 1 The Japanese in Hawaii: 1868-1967 A Bibliography of the First Hundred Years by Mitsugu Matsuda [out of print] No. 2 The Koreans in Hawaii An Annotated Bibliography by Arthur L. Gardner No. 3 Culture and Behavior in Hawaii An Annotated Bibliography by Judith Rubano No. 5 The Japanese in Hawaii by Mitsugu Matsuda A Bibliography of Japanese Americans, revised by Dennis M. O g a w a with Jerry Y. Fujioka [forthcoming] T H E CHINESE IN HAWAII An Annotated Bibliography by N A N C Y F O O N Y O U N G supported by the HAWAII CHINESE HISTORY CENTER Social Science Research Institute • University of Hawaii • Honolulu • Hawaii Cover design by Bruce T. Erickson Kuan Yin Temple, 170 N. Vineyard Boulevard, Honolulu Distributed by: The University Press of Hawaii 535 Ward Avenue Honolulu, Hawaii 96814 International Standard Book Number: 0-8248-0265-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-620231 Social Science Research Institute University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Copyright 1973 by the Social Science Research Institute All rights reserved. Published 1973 Printed in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD vii PREFACE ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi ABBREVIATIONS xii ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY 1 GLOSSARY 135 INDEX 139 v FOREWORD Hawaiians of Chinese ancestry have made and are continuing to make a rich contribution to every aspect of life in the islands. -

Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate

Fordham University DigitalResearch@Fordham Faculty Publications Jewish Studies 2020 Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs Part of the History Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fordham University, "Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate" (2020). Faculty Publications. 2. https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jewish Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Media Technology & The Dissemination of Hate November 15th, 2019-May 31st 2020 O’Hare Special Collections Fordham University & Center for Jewish Studies Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Highlights from the Fordham Collection November 15th, 2019-May 31st, 2020 Curated by Sally Brander FCRH ‘20 Clare McCabe FCRH ‘20 Magda Teter, The Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies with contributions from Students from the class HIST 4308 Antisemitism in the Fall of 2018 and 2019 O’Hare Special Collections Walsh Family Library, Fordham University Table of Contents Preface i Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate 1 Christian (Mis)Interpretation and (Mis)Representation of Judaism 5 The Printing Press and The Cautionary Tale of One Image 13 New Technology and New Opportunities 22 -

Canadian Inclusive Language Glossary the Canadian Cultural Mosaic Foundation Would Like to Honour And

Lan- guage De- Coded Canadian Inclusive Language Glossary The Canadian Cultural Mosaic Foundation would like to honour and acknowledgeTreaty aknoledgment all that reside on the traditional Treaty 7 territory of the Blackfoot confederacy. This includes the Siksika, Kainai, Piikani as well as the Stoney Nakoda and Tsuut’ina nations. We further acknowledge that we are also home to many Métis communities and Region 3 of the Métis Nation. We conclude with honoring the city of Calgary’s Indigenous roots, traditionally known as “Moh’Kinsstis”. i Contents Introduction - The purpose Themes - Stigmatizing and power of language. terminology, gender inclusive 01 02 pronouns, person first language, correct terminology. -ISMS Ableism - discrimination in 03 03 favour of able-bodied people. Ageism - discrimination on Heterosexism - discrimination the basis of a person’s age. in favour of opposite-sex 06 08 sexuality and relationships. Racism - discrimination directed Classism - discrimination against against someone of a different or in favour of people belonging 10 race based on the belief that 14 to a particular social class. one’s own race is superior. Sexism - discrimination Acknowledgements 14 on the basis of sex. 17 ii Language is one of the most powerful tools that keeps us connected with one another. iii Introduction The words that we use open up a world of possibility and opportunity, one that allows us to express, share, and educate. Like many other things, language evolves over time, but sometimes this fluidity can also lead to miscommunication. This project was started by a group of diverse individuals that share a passion for inclusion and justice. -

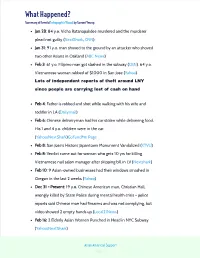

A Timeline of What Has Happened Since

What Happened? Summary of Events/Infographic Visual by Sammi Yeung Jan 28 : 84 y.o. Vicha Ratanapakdee murdered and the murderer plead not guilty (NextShark , CNN ) Jan 31 : 91 y.o. man shoved to the ground by an attacker who shoved two other Asians in Oakland (ABC News ) Feb 3 : 61 y.o. Filipino man got slashed in the subway (CBN). 64 y.o. Vietnamese woman robbed of $1000 in San Jose (Yahoo ) Lots of independent reports of theft around LNY since people are carrying lost of cash on hand Feb 4 : Father is robbed and shot while walking with his wife and toddler in LA (Dailymail ) Feb 6 : Chinese deliveryman had his car stolen while delivering food. His 1 and 4 y.o. children were in the car. ()Yahoo/NextShark GoFundMe Page Feb 8 : San Jose's Historic Japantown Monument Vandalized (KTVU ) Feb 8 : Verdict came out for woman who gets 10 yrs for killing Vietnamese nail salon manager after skipping bill in LV (Nextshark ) Feb 10 : 9 Asian-owned businesses had their windows smashed in Oregon in the last 2 weeks (Yahoo ) Dec 31 - Present : 19 y.o. Chinese American man, Christian Hall, wrongly killed by State Police during mental health crisis - police reports said Chinese man had firearms and was not complying, but video showed 2 empty hands up (Local21News ) Feb 16: 2 Elderly Asian Women Punched in Head in NYC Subway ()Yahoo/NextShark Asian American Support Page 2 Feb 16 : Flushing Asian woman got assaulted - got gashes in her head (ABC7 ) Man was released the next day without bail (Yahoo/NextShark ) Her daughter: https://www.instagram.com/p/CLYarIfDxU6/ -

Asians in Minnesota Oral History Project Minnesota Historical Society

Isabel Suzanne Joe Wong Narrator Sarah Mason Interviewer June 8, 1982 July 13, 1982 Minneapolis, Minnesota Sarah Mason -SM Isabel Suzanne Joe Wong -IW SM: I’m talking to Isie Wong in Minneapolis on June 8, 1982. And this isProject an interview conducted for the Minnesota Historical Society by Sarah Mason. Can we just begin with your parents and your family then? IW: Oh, okay. What I know about my family is basically . my family’s history is basically what I was told by my father and by my mother. So, you know,History that is just from them. Society SM: Yes. Oral IW: My father was born in Canton of a family of nine children, and he was the last one. He was the baby. And apparently they had some money because they were able to raise . I think it was four girls and the five boys. SM: Oh. Historical IW: My father’s mother died when he was about eight years old. And the father . I don’t know if I should say this, was a . .Minnesota . he was . he was addicted to opium as all men of that time were, you know. I mean, menin of money were able to smoke opium. SM: Oh. Yes. Minnesota IW: And so, little by little, he would sell off his son and his children to, you know, maintain that habit. Asians SM: Yes. IW: The mother’s dying words were, “Don’t ever sell my youngest son.” But the father just was so drugged by opium that he . eventually, he did sell my father. -

Chinese at Home : Or, the Man of Tong and His Land

THE CHINESE AT HOME J. DYER BALL M.R.A.S. ^0f Vvc.' APR 9 1912 A. Jt'f, & £#f?r;CAL D'visioo DS72.I Section .e> \% Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/chineseathomeorm00ball_0 THE CHINESE AT HOME >Di TSZ YANC. THE IN ROCK ORPHAN LITTLE THE ) THE CHINESE AT HOME OR THE MAN OF TONG AND HIS LAND l By BALL, i.s.o., m.r.a.s. J. DYER M. CHINA BK.K.A.S., ETC. Hong- Kong Civil Service ( retired AUTHOR OF “THINGS CHINESE,” “THE CELESTIAL AND HIS RELIGION FLEMING H. REYELL COMPANY NEW YORK. CHICAGO. TORONTO 1912 CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE . Xi CHAPTER I. THE MIDDLE KINGDOM . .1 II. THE BLACK-HAIRED RACE . .12 III. THE LIFE OF A DEAD CHINAMAN . 21 “ ” IV. T 2 WIND AND WATER, OR FUNG-SHUI > V. THE MUCH-MARRIED CHINAMAN . -45 VI. JOHN CHINAMAN ABROAD . 6 1 . vii. john chinaman’s little ones . 72 VIII. THE PAST OF JOHN CHINAMAN . .86 IX. THE MANDARIN . -99 X. LAW AND ORDER . Il6 XI. THE DIVERSE TONGUES OF JOHN CHINAMAN . 129 XII. THE DRUG : FOREIGN DIRT . 144 XIII. WHAT JOHN CHINAMAN EATS AND DRINKS . 158 XIV. JOHN CHINAMAN’S DOCTORS . 172 XV. WHAT JOHN CHINAMAN READS . 185 vii Contents CHAPTER PAGE XVI. JOHN CHINAMAN AFLOAT • 199 XVII. HOW JOHN CHINAMAN TRAVELS ON LAND 2X2 XVIII. HOW JOHN CHINAMAN DRESSES 225 XIX. THE CARE OF THE MINUTE 239 XX. THE YELLOW PERIL 252 XXI. JOHN CHINAMAN AT SCHOOL 262 XXII. JOHN CHINAMAN OUT OF DOORS 279 XXIII. JOHN CHINAMAN INDOORS 297 XXIV. -

Hate Lingo: a Target-Based Linguistic Analysis of Hate Speech in Social Media

Hate Lingo: A Target-based Linguistic Analysis of Hate Speech in Social Media Mai ElSherief, Vivek Kulkarni, Dana Nguyen, William Yang Wang, Elizabeth Belding University of California, Santa Barbara fmayelsherif, vvkulkarni, dananguyen, william, [email protected] Abstract However, prior work ignores a crucial aspect of hate speech – the target of hate speech – and only seeks to dis- While social media empowers freedom of expression and in- tinguish hate and non-hate speech. Such a binary distinction dividual voices, it also enables anti-social behavior, online ha- fails to capture the nuances of hate speech – nuances that rassment, cyberbullying, and hate speech. In this paper, we can influence free speech policy. First, hate speech can be deepen our understanding of online hate speech by focus- ing on a largely neglected but crucial aspect of hate speech – directed at a specific individual (Directed) or it can be di- its target: either directed towards a specific person or entity, rected at a group or class of people (Generalized). Figure 1 or generalized towards a group of people sharing a common provides an example of each hate speech type. Second, the protected characteristic. We perform the first linguistic and target of hate speech can have legal implications with re- psycholinguistic analysis of these two forms of hate speech gards to right to free speech (the First Amendment).2 and reveal the presence of interesting markers that distinguish these types of hate speech. Our analysis reveals that Directed hate speech, in addition to being more personal and directed, Directed Hate Generalized Hate is more informal, angrier, and often explicitly attacks the tar- @usr A sh*t s*cking Muslim bigot like Why do so many filthy wetback get (via name calling) with fewer analytic words and more you wouldn't recognize history if it half-breed sp*c savages live in words suggesting authority and influence. -

Civil Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990S. IYSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 343 979 UD 028 599 AUTHOR Chun, Ki-Taek; Zalokar, Nadja TITLE Civil Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. IYSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Feb 92 NOTE 245p. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Access to Education; *Asian Americans; *Civil Rights; Educational Discrimination; Elementary Secondary Education; Equal Educetion; *Equal Opportunities (Jobs); Ethnic Discrimination; Higher Education; Immigrants; Minority Groups; *Policy Formation; Public Policy; Racial Bias; *Racial Discrimination; Violence IDENTIFIERS *Commission on Civil Rights ABSTRACT In 1989, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights held a series of roundtable conferences to learn about the civil rights concerns of Asian Americans within their communities. Using information gathered at these conferences as a point of departure, the Commission undertook this study of the wide-ranging civil rights issues facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. Asian American groups considered in the report are persons having origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. This report presents the results of that investigation. Evidence is presented that Asian Americans face widespread prejudice, discrimination, and barriers to equal opportunity. The following chapters highlight specificareas: (1) "Introduction," an overview of the problems;(2) "Bigotry and Violence Against Asian Americans"; (3) "Police Community Relations"; (4) "Access to Educational Opportunity: Asian American Immigrant Children in Primary and Secondary Schools";(5) "Access to Educational Opportunity: Higher Education"; (6) "Employment Discrimination";(7) "Other Civil Rights Issues Confronting Asian AmericansH; and (8) "Conclusions and Recommendations." More than 40 recommendations for legislative, programmatic, and administrative efforts are made. -

On the Power of Slurring Words and Derogatory Gestures

Charged Expressions: On the Power of Slurring Words and Derogatory Gestures Ralph DiFranco, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2016 Slurs have the striking power to promulgate prejudice. Standard semantic and pragmatic theories fail to explain how this works. Drawing on embodied cognition research, I show that metaphorical slurs, descriptive slurs, and slurs that imitate their targets are effective means of transmitting prejudice because they are vehicles for prompting hearers to form mental images that depict targets in unflattering ways or to simulate experiential states such as negative feelings for targets. However, slurs are a heterogeneous group, and there may be no one mechanism by which slurs harm their targets. Some perpetrate a visceral kind of harm – they shock and offend hearers – while others sully hearers with objectionable imagery. Thus, a pluralistic account is needed. Although recent philosophical work on pejoratives has focused exclusively on words, derogation is a broader phenomenon that often constitutively involves various forms of non- verbal communication. This dissertation leads the way into uncharted territory by offering an account of the rhetorical power of iconic derogatory gestures and other non-verbal pejoratives that derogate by virtue of some iconic resemblance to their targets. Like many slurs, iconic derogatory gestures are designed to sully recipients with objectionable imagery. I also address ethical issues concerning the use of pejoratives. For instance, I show that the use of slurs for a powerful majority -

Race and Cricket: the West Indies and England At

RACE AND CRICKET: THE WEST INDIES AND ENGLAND AT LORD’S, 1963 by HAROLD RICHARD HERBERT HARRIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2011 Copyright © by Harold Harris 2011 All Rights Reserved To Romelee, Chamie and Audie ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My journey began in Antigua, West Indies where I played cricket as a boy on the small acreage owned by my family. I played the game in Elementary and Secondary School, and represented The Leeward Islands’ Teachers’ Training College on its cricket team in contests against various clubs from 1964 to 1966. My playing days ended after I moved away from St Catharines, Ontario, Canada, where I represented Ridley Cricket Club against teams as distant as 100 miles away. The faculty at the University of Texas at Arlington has been a source of inspiration to me during my tenure there. Alusine Jalloh, my Dissertation Committee Chairman, challenged me to look beyond my pre-set Master’s Degree horizon during our initial conversation in 2000. He has been inspirational, conscientious and instructive; qualities that helped set a pattern for my own discipline. I am particularly indebted to him for his unwavering support which was indispensable to the inclusion of a chapter, which I authored, in The United States and West Africa: Interactions and Relations , which was published in 2008; and I am very grateful to Stephen Reinhardt for suggesting the sport of cricket as an area of study for my dissertation. -

The US and the World: Chinese Immigrants

The U.S. and the World: Chinese Immigrants Instructions This module will introduce the history of Chinese immigrants in the nineteenth century. It will also show one of the ways that the U.S. was (and is) connected to the rest of the world. Begin by reading the article “For Further Information.” This will provide you with information about the immigrants, the world they came from and their lives in the United States. A crucial part of this history is the hostility they encountered and the eventual legislation that stopped almost all Chinese immigration. The four documents, which you should read next, show both the hostility toward the Chinese and the viewpoints of two of their defenders. When you have read the article and the documents, take the quiz and participate in the discussion. For Further Information: Chinese Immigrants to America, 1849-1882 In January, 1848 a workman at a mill east of what became Sacramento, California discovered gold. New of this discovery spread rapidly over most of the world, and gold seekers from many nations flooded into California. Among the immigrants were thousands of Chinese farmers from the Pearl River delta in southeastern China. By 1851 25,000 had arrived in California, where they made up one quarter of the total population. Most of the immigrants were young men from farming families in Guangdong province. This area was located close to the port city of Guanzhou, known in the West as Canton. For many years it had been the center of foreign trade in China and until the first Opium War (1839-42) was the only port that allowed Westerners—from the United States, Britain, and other European countries—to enter China.