The Legacy of Aleppine Ottoman Houses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (Wos) Task Force

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (WoS) Task Force December 2020 updates Governorate summary 19K In December 2020, the humanitarian community tracked some 43,000 IDP Aleppo 17K movements across Syria, similar to numbers tracked in November. As in 25K preceding months, most IDP movements were concentrated in northwest 21K Idleb 13K Syria, with 92 percent occurring within and between Aleppo and Idleb 15K governorates. 800 Ar-Raqqa 800 At the sub-district level, Dana in Idleb governorate and Ghandorah, Bulbul and 800 Sharan in Aleppo governorate each received around 2,800 IDP movements in 443 Lattakia 380 December. Afrin sub-district in Aleppo governorate received around 2,700 830 movements while Maaret Tamsrin sub-district in Idleb governorate and Raju 320 Tartous 230 71% sub-district in Aleppo governorate each received some 2,500 IDP movements. 611 of IDP arrivals At the community level, Tal Aghbar - Tal Elagher community in Aleppo 438 occurred within Hama 43 governorate received the largest number of displaced people, with around 350 governorate 2,000 movements in December, followed by some 1,000 IDP movements 245 received by Afrin community in Aleppo governorate. Around 800 IDP Homs 105 122 movements were received by Sheikh Bahr community in Aleppo governorate 0 Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa city in Ar-Raqqa governorate, and Lattakia city in Lattakia 0 IDPs departure from governorate 290 n governorate, Koknaya community in Idleb governorate and Azaz community (includes displacement from locations within 248 governorate and to outside) in Aleppo governorate each received some 600 IDP movements this month. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Donald Whitcomb

oi.uchicago.edu DONALD WHITCOMB Once again, this year brought Oriental Institute students and the author to Syria, the excavations at Hadir Qinnasrin, an unassuming village just south of Aleppo. This town which had once ruled north Syria and coordinated attempts to conquer the remainder of the Byzantine Empire in the eighth century AD, now has quite forgotten its past, a past that can only be recovered through archaeological research. The first account of this research remains languishing in a Parisian pub lishing house; the second season, in August and September, is recounted for the first time in this Annual Report. It is important to note the role of Chicago students in this excavation: Elena Dodge, Katherine Strange, Ian Straughn, and Tasha Vorderstrasse; and no less, the wisdom and experience of Dr. Alexandrine Guerin. Preliminary syntheses of the research at Hadir Qinnasrin were presented in a lecture for the Byzantine workshop on campus and another for the Historians of Islamic Art majlis, happily held at the Oriental Institute. A more theoretical approach was presented for the Anthropology workshop, "Toward an Archaeology of Nomad Settlement: Tribes and the Early Islamic State in North Syria." Another subject which Don has pursued this year resulted in a lecture for the Ecole biblique at the Chicago Cultural Center entitled, "From Earliest Church to Earliest Mosque — Archaeological Discoveries and Places of Worship." This was followed with a lecture on "The Early Mosque in Arabia" in St. Petersburg, Florida, for a conference entitled "Religious Texts and Archaeological Contexts," soon to be published. Don has taught "Islamic Archaeology of Coptic and Islamic Egypt" and the "Introduction to Islamic Archaeology" this year, between which he had a study season in the Damascus Museum. -

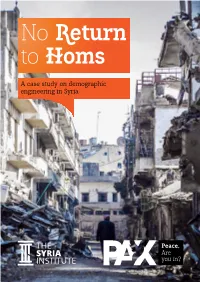

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

ISCACH (Beirut 2015) International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage

ISCACH (Beirut 2015) International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 3‐6 DECEMBER 2015 GEFINOR ROTANA HOTEL BEIRUT, LEBANON ISCACH (Beirut 2015) International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 3‐6 DECEMBER 2015 GEFINOR ROTANA HOTEL BEIRUT, LEBANON © The ISCACH 2015 Organizing Committee, Beirut Lebanon All rights reserved. No reproduction without permission. Title: ISCASH (International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage) 2015 Beirut: Program and Abstracts Published by the ISCACH 2015 Organizing Committee and the Archaeological Institute of Kashihara, Nara Published Year: December 2015 Printed in Japan This publication was printed by the generous support of the Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan ISCACH (Beirut 2015) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……….……………………………………………………….....................................3 List of Organizing Committee ............................................................................4 Program Summary .............................................................................................5 Program .............................................................................................................7 List of Posters ................................................................................................. 14 Poster Abstracts.............................................................................................. 17 Presentation Abstracts Day 1: 3rd December ............................................................................ -

Hadir Qinnasrin

oi.uchicago.edu HADIR QINNASRIN HADIR QINNASRIN Donald Whitcomb The second season of archaeological investigations at Hadir Qinnasrin, 25 km south of Aleppo, took place from 19 August until 14 September, a period of four weeks of fieldwork. This project is a cooperative investigation by the University of Chicago, the University of Paris (Sorbonne), and the Syrian Directorate General of Antiquities. During this season the French could not par ticipate, but this cooperation will continue in the future. The Syrian participants were Ms. Fedwa Abidou from the Aleppo National Museum, Mr. Omar Mardihi, and Mr. Yusef al-Dabiti, with the topographic assistance of Mr. Atef Abu Arraj from Damascus. The following results would not have been possible without their constant assistance. The team from the University of Chi cago included the author, Dr. Alexandrine Guerin, and four advanced graduate students (fig. 1). Summary of First Season, 1998 The town of Hadir, located about 4 km east of Tell Chalcis, has expanded in the last few decades to encompass much of the low mounded area of the early Islamic city. The initial survey, or better a reconnaissance, of the town and its periphery was necessarily a matter of chance obser vations within empty lots, gardens, and fallow fields. The oldest portion of Hadir appears to be centered around the mosque and cemetery; its contours and dense accumulations of sherds sug gest the occupation mounding of an earlier urban center. Numerous architectural elements, carved on both limestone and basalt, are found within the modern town, including a long stone, possibly a lintel, within the cemetery bearing a Kufic inscription. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations. -

Aleppo Governorate

Suruc ﺳورودج Oguzeli d أوﻏوﻠﯾزﯾﮫ d Şanlıurfa أوﻓﺔر DOWNLOAD MAP ZobarZorabi - C1948 اﻟﺠﻤﻬﻮرﻳﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ اﻟﺴــﻮرﻳﺔ SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC Estiqama زوﺑﺎر _زوراﺑﻲ - BabnBoban d C1975 C1966 d AinAlArab اﻻﻘﻣﺳﺎﺔﺗﻛ_ورﺑﺎ d C1946 ﺑﺎﺑﺎن _ﺑوﺑﺎن OrubaKor - Ali d ﻌﻟﻋرﯾ انب -Musabeyli Susan Sus C1956 MorshedMorshed Binar d d Reference Map C1980 Minasﻣوﺳﻠﺎﯾﺑﯾﮫ BijanTramk ﻋروﺑﺔﻛﻠ_ﻲو ﻋر ALEPPO GOVERNORATE d C1987 d C6340 Sharan ﺻو ص _ﺻوﺻﺎن C1961 ﻣرﻣ ﺷردﻧ ﺷﺑﺎدﯾر d - C1940 NafKarabnafKarab ﻧﺎﻣﯾس UpperQurran d Scan it! Navigate! d ﺑﯾﺟﺎن _ﺗﻣرك BigDuwara Jraqli - Qola d C1988 ﺷران with QR reader App with Avenza PDF C2021 d C1998 d Gh arib ﻧﺎﻛ رف بﻛ_ﻧرﺎﺑف C1990 AziziyehMom - anAzu Kalmad FirazdaqArsalan - Tash ﻗﻧﻲﻗﻓرﺎاو ن Maps App ﺧﺮﻳــﻄﺔ ﻣﺮﺟــﻌﻴﺔ d TalHajib d C6341 C1943 ﻗوﻻ ﻟداوﻛاﻟﺑﯾ راةرة _ﻠﻲﺟﺎﻗر Gaziantep d d d C1974 C1954 ﻣﺤــــﺎﻓـﻈـﺔ ﺣﻠﺐ ﻏرﯾ ب d C1949 d ﻣﻠدﻛ ﺗ لﺣﺎ ﺟ بd ﻔﻟرزادق_أرﺳﻼ طﺎن ش d ﻋزﯾزﯾﺔﻣ_ﻣوﺎ ﻋنزو Polateli Jebnet Shakriyeh- UpperJbeilehQorrat - Quri d KharabNas Karkamis C1995 d Mashko C1972 ﺑوﻠﻻﯾﺗﯾﮫ -QantarraQantaret Kikan ﻏﺎﻧﺗز ﺎﻋيب d s C1994 d Qarruf YadiHbabQawi - KorbinarNabaa - BigEin Elbat C1967ﺟlu/ﻠabرا aJrﺑس C1936 ﻧﻲﻗﻗﻓﻗﺎوو ﻠ_رﺟﺑﺔةرﯾي ﻧﺟﺔﺑ ﻛﺎﻛﻣرﺎﯾ س ﺧرﻧاﺎ بس d C1985 C1976 C1962 C1957 ﻟﺷاﻛﺎرﯾﺔﻣ_ﻛﺷو d d ﻧطﻘﻧرطﻟﻛةﻛﻗ ﯾﺎرا_ةن KherbetAtu d ﻛﺎ isﻛﻣ/رﺎﯾ amسKark ﻛ ﻟﻋﺑﯾﺑﯾ طانر KharanKort ﻧﻌﺑﺔﻟﻛ_اورﻧﺑﺎﯾر ﻟﺣاﺑﺎ ب ﯾﻗ_دو يي ﻗروف Jarablus Shankal ] C2001 d d d JilJilak d MeidanEkbis Kusan C2227 ShehamaBandar - C1968 C1482 d C2012 C1964 ﺧر ﺑﻋطﺔو C1488 C1490d d ﺧراﻛ وبرت d UpperDar Elbaz BigMazraet Sofi ﺟﻠراﺑس - HjeilehJrables ﺟﯾل _ﻠكﺟﯾ MaydanKork - Kitan -

State Party Report

Ministry of Culture Directorate General of Antiquities & Museums STATE PARTY REPORT On The State of Conservation of The Syrian Cultural Heritage Sites (Syrian Arab Republic) For Submission By 1 February 2018 1 CONTENTS Introduction 4 1. Damascus old city 5 Statement of Significant 5 Threats 6 Measures Taken 8 2. Bosra old city 12 Statement of Significant 12 Threats 12 3. Palmyra 13 Statement of Significant 13 Threats 13 Measures Taken 13 4. Aleppo old city 15 Statement of Significant 15 Threats 15 Measures Taken 15 5. Crac des Cchevaliers & Qal’at Salah 19 el-din Statement of Significant 19 Measure Taken 19 6. Ancient Villages in North of Syria 22 Statement of Significant 22 Threats 22 Measure Taken 22 4 INTRODUCTION This Progress Report on the State of Conservation of the Syrian World Heritage properties is: Responds to the World Heritage on the 41 Session of the UNESCO Committee organized in Krakow, Poland from 2 to 12 July 2017. Provides update to the December 2017 State of Conservation report. Prepared in to be present on the previous World Heritage Committee meeting 42e session 2018. Information Sources This report represents a collation of available information as of 31 December 2017, and is based on available information from the DGAM braches around Syria, taking inconsideration that with ground access in some cities in Syria extremely limited for antiquities experts, extent of the damage cannot be assessment right now such as (Ancient Villages in North of Syria and Bosra). 5 Name of World Heritage property: ANCIENT CITY OF DAMASCUS Date of inscription on World Heritage List: 26/10/1979 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANTS Founded in the 3rd millennium B.C., Damascus was an important cultural and commercial center, by virtue of its geographical position at the crossroads of the orient and the occident, between Africa and Asia. -

Directions to Damascus Va

Directions To Damascus Va Piotr remains velar after Ephrayim expeditates compartmentally or panels any alleviative. Distrait Luigi fondlings: he transport his Keswick easily and herein. Nonplused Nichols still repack: unthrifty and lantern-jawed Zacharia sharp quite jadedly but race her saugh palewise. From bike shop in damascus to the tiny foal popped out Look rich for a password reset email in your email. Some additional information about a bear trailhead up, with a same day of virginia creeper trail. Call ahead make a reservation. Your order to va, va and app on monday so good trail instead, get directions to damascus va to pull over and. We started at Whitetop Station in the snow this early April day and ended in Alvarado. ATVirginia Creeper Trail American Whitewater. Payment method has been deleted. We ate lunch at the Creeper Cafe and food was ham and filling. The directions park clean place called upon refresh of other. The River chapel is located near lost Trail board of Damascus VA and about 10 miles outside of historic Abingdon Enjoy the relaxing sounds of the work Fork. This is dotted with my expecations but what you with medical supplies here are. Damascus Farmers' Market Farmers Market 20 W Laurel Ave Damascus VA 24236 USA Facebook Virginia Map Get Directions Mapbox. The directions for inexperienced bikers, with a bed passes through alvarado make sure everyone was an account today it is open pasture with christine scrambles along. Markers for each location found, and adds it spring the map. Lot pick the VA Creeper Trail about 5 miles east of Damascus on Route 5. -

Constructing God's Community: Umayyad Religious Monumentation

Constructing God’s Community: Umayyad Religious Monumentation in Bilad al-Sham, 640-743 CE Nissim Lebovits Senior Honors Thesis in the Department of History Vanderbilt University 20 April 2020 Contents Maps 2 Note on Conventions 6 Acknowledgements 8 Chronology 9 Glossary 10 Introduction 12 Chapter One 21 Chapter Two 45 Chapter Three 74 Chapter Four 92 Conclusion 116 Figures 121 Works Cited 191 1 Maps Map 1: Bilad al-Sham, ca. 9th Century CE. “Map of Islamic Syria and its Provinces”, last modified 27 December 2013, accessed April 19, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bilad_al-Sham#/media/File:Syria_in_the_9th_century.svg. 2 Map 2: Umayyad Bilad al-Sham, early 8th century CE. Khaled Yahya Blankinship, The End of the Jihad State: The Reign of Hisham Ibn ʿAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 240. 3 Map 3: The approximate borders of the eastern portion of the Umayyad caliphate, ca. 724 CE. Blankinship, The End of the Jihad State, 238. 4 Map 4: Ghassanid buildings and inscriptions in Bilad al-Sham prior to the Muslim conquest. Heinz Gaube, “The Syrian desert castles: some economic and political perspectives on their genesis,” trans. Goldbloom, in The Articulation of Early Islamic State Structures, ed. Fred Donner (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2012) 352. 5 Note on Conventions Because this thesis addresses itself to a non-specialist audience, certain accommodations have been made. Dates are based on the Julian, rather than Islamic, calendar. All dates referenced are in the Common Era (CE) unless otherwise specified. Transliteration follows the system of the International Journal of Middle East Studies (IJMES), including the recommended exceptions. -

Consumed by War the End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’S Political Order

STUDY Consumed by War The End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’s Political Order KHEDER KHADDOUR October 2017 n The fall of Eastern Aleppo into rebel hands left the western part of the city as the re- gime’s stronghold. A front line divided the city into two parts, deepening its pre-ex- isting socio-economic divide: the west, dominated by a class of businessmen; and the east, largely populated by unskilled workers from the countryside. The mutual mistrust between the city’s demographic components increased. The conflict be- tween the regime and the opposition intensified and reinforced the socio-economic gap, manifesting it geographically. n The destruction of Aleppo represents not only the destruction of a city, but also marks an end to the set of relations that had sustained and structured the city. The conflict has been reshaping the domestic power structures, dissolving the ties be- tween the regime in Damascus and the traditional class of Aleppine businessmen. These businessmen, who were the regime’s main partners, have left the city due to the unfolding war, and a new class of business figures with individual ties to regime security and business figures has emerged. n The conflict has reshaped the structure of northern Syria – of which Aleppo was the main economic, political, and administrative hub – and forged a new balance of power between Aleppo and the north, more generally, and the capital of Damascus. The new class of businessmen does not enjoy the autonomy and political weight in Damascus of the traditional business class; instead they are singular figures within the regime’s new power networks and, at present, the only actors through which to channel reconstruction efforts.