World-Building, Dangerous Magic and Jane Austen: a Conversation with Sean Williams Gillian Dooley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transgender-Industrial Complex

The Transgender-Industrial Complex THE TRANSGENDER– INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX Scott Howard Antelope Hill Publishing Copyright © 2020 Scott Howard First printing 2020. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, besides select portions for quotation, without the consent of its author. Cover art by sswifty Edited by Margaret Bauer The author can be contacted at [email protected] Twitter: @HottScottHoward The publisher can be contacted at Antelopehillpublishing.com Paperback ISBN: 978-1-953730-41-1 ebook ISBN: 978-1-953730-42-8 “It’s the rush that the cockroaches get at the end of the world.” -Every Time I Die, “Ebolarama” Contents Introduction 1. All My Friends Are Going Trans 2. The Gaslight Anthem 3. Sex (Education) as a Weapon 4. Drag Me to Hell 5. The She-Male Gaze 6. What’s Love Got to Do With It? 7. Climate of Queer 8. Transforming Our World 9. Case Studies: Ireland and South Africa 10. Networks and Frameworks 11. Boas Constrictor 12. The Emperor’s New Penis 13. TERF Wars 14. Case Study: Cruel Britannia 15. Men Are From Mars, Women Have a Penis 16. Transgender, Inc. 17. Gross Domestic Products 18. Trans America: World Police 19. 50 Shades of Gay, Starring the United Nations Conclusion Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Introduction “Men who get their periods are men. Men who get pregnant and give birth are men.” The official American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Twitter account November 19th, 2019 At this point, it is safe to say that we are through the looking glass. The volume at which all things “trans” -

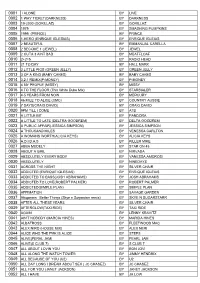

DJ Playlist.Djp

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

Garbage & the Temper Trap Join for Next Winery Series!

Media Release – Thursday July 28 GARBAGE & THE TEMPER TRAP JOIN FOR NEXT WINERY SERIES! With the Preatures, Tash Sultana and Adalita a day on the green has assembled an epic line-up for its next series of winery concerts. Alt-rock pioneers Garbage and Australia’s own multi-platinum chart toppers The Temper Trap will come together as part of their respective national tours for five outdoor events through November/December. The concerts will feature a stellar under-card with special guests The Preatures, Tash Sultana and Adalita. The five band bill kicks off at Victoria’s Rochford Wines on Saturday November 26. These will be the Garbage’s first Australian shows since 2013 and celebrate their acclaimed sixth studio album Strange Little Birds (out now via Liberator Music). To create Strange Little Birds, their first album in four years, Garbage (Shirley Manson, Steve Marker, Duke Erikson and Butch Vig) drew on a variety of influences including the albums they loved growing up. Upon its June release, the album debuted at #9 on the ARIA Album Chart and picked up widespread acclaim: ‘20-plus years after forming, each band member is still fired up to mine new sounds and approaches for inspiration. That willingness to be uncomfortable and look beneath the surface makes Strange Little Birds a rousing success.’ – The A.V. Club ‘The electronic rockers return with a sixth studio album as cool and caustic as their 1995 debut’ – NME ‘Garbage haven’t released an album this immediate, melodically strong and thematically interesting since their self-titled 1995 debut.’ – Mojo In support of the album’s release, Garbage performed a powerful two-song performance on Jimmy Kimmel Live! – watch ‘Empty’ here and ‘Push It’ here. -

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document cannot be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. 1 Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in established music trade publications. Please provide DotMusic with evidence that such criteria is met at [email protected] if you would like your artist name of brand name to be included in the DotMusic GPML. GLOBALLY PROTECTED MARKS LIST (GPML) - MUSIC ARTISTS DOTMUSIC (.MUSIC) ? and the Mysterians 10 Years 10,000 Maniacs © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document 10cc can not be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part 12 Stones without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. Visit 13th Floor Elevators www.music.us 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2 Unlimited Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. 3 Doors Down Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in 30 Seconds to Mars established music trade publications. Please -

Australian Science Fiction: in Search of the 'Feel' Dorotta Guttfeld

65 Australian Science Fiction: in Search of the ‘Feel’ Dorotta Guttfeld, University of Torun, Poland This is our Golden Age – argued Stephen Higgins in his editorial of the 11/1997 issue of Aurealis, Australia’s longest-running magazine devoted to science fiction and fantasy. The magazine’s founder and editor, Higgins optimistically pointed to unprecedented interest in science fiction among Australian publishers. The claim about a “Golden Age” echoed a statement made by Harlan Ellison during a panel discussion “The Australian Renaissance” in Sydney the year before (Ellison 1998, Dann 2000)64. International mechanisms for selection and promotion in this genre seemed to compare favorably with the situation of Australian fiction in general. The Vend-A-Nation project (1998) was to encourage authors to write science fiction stories set in the Republic of Australia, and 1999 was to see the publication of several scholarly studies of Australian science fiction, including Russell Blackford’s and Sean McMullen’s Strange Constellations. Many of these publications were timed to coincide with the 1999 ‘Worldcon’, the most prestigious of all fan conventions, which had been awarded to Melbourne. The ‘Worldcon’ was thus about to become the third ‘Aussiecon’ in history, accessible for the vibrant fan community of Australia, and thus sure to provide even more impetus for the genres’ health. And yet, in the 19/2007 issue of Aurealis, ten years after his announcement of the Golden Age, Stephen Higgins seems to be using a different tone: Rather than talk of a new Golden Age of Australian SF (and there have been plenty of those) I prefer to think of the Australian SF scene as simply continuing to evolve. -

ADJS Top 200 Song Lists.Xlsx

The Top 200 Australian Songs Rank Title Artist 1 Need You Tonight INXS 2 Beds Are Burning Midnight Oil 3 Khe Sanh Cold Chisel 4 Holy Grail Hunter & Collectors 5 Down Under Men at Work 6 These Days Powderfinger 7 Come Said The Boy Mondo Rock 8 You're The Voice John Farnham 9 Eagle Rock Daddy Cool 10 Friday On My Mind The Easybeats 11 Living In The 70's Skyhooks 12 Dumb Things Paul Kelly 13 Sounds of Then (This Is Australia) GANGgajang 14 Baby I Got You On My Mind Powderfinger 15 I Honestly Love You Olivia Newton-John 16 Reckless Australian Crawl 17 Where the Wild Roses Grow (Feat. Kylie Minogue) Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds 18 Great Southern Land Icehouse 19 Heavy Heart You Am I 20 Throw Your Arms Around Me Hunters & Collectors 21 Are You Gonna Be My Girl JET 22 My Happiness Powderfinger 23 Straight Lines Silverchair 24 Black Fingernails, Red Wine Eskimo Joe 25 4ever The Veronicas 26 Can't Get You Out Of My Head Kylie Minogue 27 Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun 28 Sweet Disposition The Temper Trap 29 Somebody That I Used To Know Gotye 30 Zebra John Butler Trio 31 Born To Try Delta Goodrem 32 So Beautiful Pete Murray 33 Love At First Sight Kylie Minogue 34 Never Tear Us Apart INXS 35 Big Jet Plane Angus & Julia Stone 36 All I Want Sarah Blasko 37 Amazing Alex Lloyd 38 Ana's Song (Open Fire) Silverchair 39 Great Wall Boom Crash Opera 40 Woman Wolfmother 41 Black Betty Spiderbait 42 Chemical Heart Grinspoon 43 By My Side INXS 44 One Said To The Other The Living End 45 Plastic Loveless Letters Magic Dirt 46 What's My Scene The Hoodoo Gurus -

Screamfeeder – Kitten Licks Review

Screamfeeder - Kitten Licks in Releases : Mess+Noise http://www.messandnoise.com/releases/2000325 Features Music TV Discussions Events Tickets Log In or Joinscreamfeeder Search RECORD REVIEWS Share This RELATED M+N CONTENT Screamfeeder Screamfeeder Track: Summertime Screamfeeder Kitten Licks The Troubadour, Brisbane, May 9 09 Reviewing this Screamfeeder set should be easy. It's a Hearing Screamfeeder’s 1996 opus ‘Kitten Licks’ is like being transported back to known outcome: a full performance o... an indie-rock golden age, writes DARREN LEVIN. Licks From ’96 Brisbane indie pop heroes Screamfeeder will reprise their 1996 album '... How can one album transcend the zeitgeist and Screamfeeder Reprise ‘Kitten Licks’ yet be utterly of its time? In the vein of ATP’s “Don’t Look Back” concert series, Screamfeeder wi... Hearing Screamfeeder’s Kitten Licks again is a Brisbane Rock Snaps Exposed transportive experience, The work of Brisbane’s leading rock photographers will be showcased at... like watching a film you loved as a kid or flipping through an old album of family photos. It instantly conjures memories of eyebrow rings and bottle dye, of waking up early for Recovery and staying up late to watch Rage. It makes judging a reissue like this on musical merits alone a difficult ask, because it’s wrapped up in the kind of nostalgia that irons out all kinks. TRACKLISTING I first heard Kitten Licks as a teenager in mid-1996, a time when Australian indie – stuck for so long in 1. Static the quagmire of grunge – finally began to develop an identity of its own. -

Media Kit 2012 New Look

VICTORIA’S HIGHEST CIRCULATING STREETPRESS • WEDNESDAY 2 NOVEMBER 2011 ~ ISSUE 1198 ~ FREE WIN: LTD George Lynch GL600V Signature Guitar valued at $2399 ISSUE 68 SUMMER 2011 DAEDELUS LAURA JEAN SNEAKY SOUND SYSTEM DESTRUCTION FAKER THE FLAMING LIPS FLORENCE & THE GEOFFREY MACHINE O'CONNOR MELBOURNE - MORNINGTON PENINSULA - BALLARATAT/BENDIGOGEELONG/SURFC / BENDIGO - GEELONG / SURF COASTOAST 33,253 QUEENSLAND'S HIGHEST CIRCULATING STREET PRESS • 2 NOVEMBER 2011 • 1551 • FREE THE DRONES’ GARETH LIDDIARD MEETS MAGIC DIRT’S ADALITA SIDNEY SAMSON SIDNEY DESTRUCTION CARS CARSICK GROUP CHARGE SHAPESHIFTER NIKKO FOLK UKE PAUL CHINA THE VASCO ERA BRISBANE / GOLD COASTCOAST/SUNSHINECOAST/BYRON / SUNSHINE COAST / BYRONN BAYB AY 20,26220,26 MEET JORDIE LANE WA’S HIGHEST QUALITY STREET PRESS • THURSDAY 15 DECEMBER 2011 • 268 • FREE POWDERFINGER’S COGS MEETS THE GETAWAY PLAN’S AARON THE NEW YORK DOLLS PLUSPLUS •JOEJ SATRIANI TALKST CHICKENFOOT MEET THE MERCY KILLS • HUSKY’SHUSKY’S GIDEONGIDEO PREISS TALKS KEYBOARDS • SYNDICATE ROADRO TEST THE TASCAM DR-100 • CHRISTMASCHRISTMAS MUSICALM GIFT GUIDE • LATEST MUSICMUSIC GEAR ROAD TESTED WHO IS AUSTRALIA’S MOST IMPORTANT MUSICIAN? LYRICS BORN RYAN ADAMS FLEET FOXES Z Z T VVOTE AND GO INTO DRAW TO WIN A BOSS EFFECT PEDAL PACK AM magazine 1 INSIDE: TOTALLY ENORMOUS EXTINCT DINOSAURS • TRENTEMØLLER • STEREO MCS www.themusic.com.au NEW LOOK FROM 1ST ISSUE 2012 MEDIA KIT 2012 ABOUT THE MAGAZINE Australian Musician magazine is Australia’s longest running publication for contemporary musicians. Australian Musician is aimed at musicians of all levels, from those just starting out looking for guidance to professional working players seeking to keep up to date with the latest music gear and trends. -

Doctor of Philosophy

A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences University of Western Sydney March 2007 ii CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................ VIII LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................... VIII LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS ............................................................................ IX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................................................. X STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP .................................................................. XI PRESENTATION OF RESEARCH............................................................... XII SUMMARY ..................................................................................................XIV CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCING MUSIC FESTIVALS AS POSTMODERN SITES OF CONSUMPTION.............................................................................1 1.1 The Aim of the Research ................................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Consumer Society............................................................................................................................. 8 1.3 Consuming ‘Youth’........................................................................................................................ 10 1.4 Defining Youth .............................................................................................................................. -

SS&H Journal Lhg.UG S46 the UNIVERSITY of QUEENSLAND

SS&H Journal THE UNIVERSITY LHg.UG S46 OF QUEENSLAND LIBRARY Semper floreiHr; £003 x^ Received on: 04-11-03 SEMPER FLOREAT ENDGAME EDITION 2003 Contents: Indigenous people have been, often violently, dispossessed of their land EDITORIALS and culture. They remain some of the most marginalised in our society. STUFF There can be no social progress without recognition of the Injustices Dream Job in the Last Stalinist State 6 suffered by Indigenous Australians. A Test not Primarily of Speed 7 Interview with John Birmingham 8 Dude, Where's my haggis? 11 The End 12 SEMPER FLOREAT Inconceivable: A life without music 13 THE UQ UNION NEWSPAPER Whinge for a whinge, More Whinging, and Whinge 14 Aunty Jan: I Need a Man 16 Unleash the Gimp 19 Editors: David Lavercombe Shona Nystrom UNION STUFF Jim Wilson Arts Editor: Sofia Ham What you need to know and do when you vote. 20 What student politicians mean when they say 21 Polling places and times 21 Telephone: 3377 2237 President's report 22 Facsimile: 3377 2220 Resignation 25 [email protected] Annual Budget 26 Paying the Printer _ 26 27 Semper Floreat Offices Red Room Incident 27 Union Complex Idle Threats 'Yes' campaign 28 The University of Queensland On being defamed, and Mojo mumbo jumbo 29 St Lucia, 4067 How to Succeed in the UQ Union 30 Quotes from the year 34 The views expressed in Semper Floreat do not necessarily reflect OTHER STUFF those of the editors, the UQ Union, or The University of Queensland. To my friends in the Ministry of Truth. -

University of Wollongong Union Annual Report 2003 University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Union Annual Reports Corporate Publications Archive 2003 University of Wollongong Union Annual Report 2003 University of Wollongong Recommended Citation University of Wollongong, "University of Wollongong Union Annual Report 2003" (2003). University of Wollongong Union Annual Reports. 35. http://ro.uow.edu.au/uowunionannrep/35 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] University of Wollongong Union Annual Report 2003 This journal article is available at Research Online: http://ro.uow.edu.au/uowunionannrep/35 annual report 03 Your UniBar! Award-winning design Coffee Shop Snack stop Entertainment venue Chill-out zone Mon to Sat. 1 annual report for the year ended 31 december 03 2 introduction 1 • organisational structure board of directors 3-4 major achievements 5-6 • awards • marketing research • OH & S developments adding value to the uow experience 6-14 CSD the centre for student development • employment experience program •directors’ green team report • dj comp • post office • certificate under section 41C(1C) of Introduction •director’s project challenge declaration • poetry comp • conferences & the public finance • training & development functions certificate under • acquisitive art award audit act statement We are an essential workshops section 41C(1C) of other events • shoalhaven campus of financial service to the •theunicrew public finance services • annual dinner performance University and •auditunicentre act student facilities & support • clubs & societies • statement of statementdevelopment of committeefinancial services 21-26 financial position add value to the performance • o week • the university of arizona • enquiries & ticket • statement of cash Wollongong statement‘blue chip’ program of financial • international week counter flows position experience. -

Finalist Catalogue & Voting Slip

Melbourne Finalist Prize for Music Catalogue & 2016 Voting Slip Finalist Exhibition Federation Square 7–21 November 2016 Our 2016 Partners and Patrons 06 About the Finalist Exhibition 08 2016 Prize & Awards 10 Civic Choice Award 2016 Voting Slip 13 Government Partners 15 Judges 16 Melbourne Prize Alumni 20 Melbourne Prize for Music 2016 22 Outstanding Musicians Award 2016 30 Beleura Award for Composition 2016 42 Development Award 2016 50 Distinguished Musicians Fellowship 2016 58 Thank You 60 About the Melbourne Prize Trust 62 What’s What’s Inside 6 Thank you to our 7 2016 Partners A Message from the Executive Director of the and Patrons Melbourne Prize Trust Thank you to our 2016 partners and patrons The Melbourne Prize Trust is I would like to thank our pleased to present the Melbourne esteemed judging panel for their Prize for Music 2016 and Awards, time and dedication to the Prize. offered as part of the annual We are delighted to also have Melbourne Prize cycle. Chong Lim as an advisor. This year we are delighted Our finalists in all categories to provide opportunities for are showcased at the exhibition Diana Gibson AO Victorian musicians across all held between 7 and 21 November music genres. The 2016 program 2016, where a free catalogue is Dr. Ron Benson would not be possible without available. Vote for a finalist to win the generous support of all our the $4,000 Civic Choice Award partners and patrons – thank you 2016 on our website. one and all. The Trust is proud to have The Melbourne Prize for Music the Victorian Government, 2016 and Awards is one of the through Creative Victoria, and most valuable music prizes in the City of Melbourne, through Australia, with a prize and Melbourne Music Week 2016, award pool of over $130,000.