Peak Music Experiences: a New Perspective on Popular Music, Identity and Scenes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Nature's Wonders

CAMPUS TIMES MARCH 31, 2006 SERVING THE UNIVERSITY OF LA VERNE COMMUNITY SINCE 1919 VOL. 114, NO. 19 Panelists advocate Exploring nature’s wonders for peace Laura Bucio Assistant Editor A panel of renowned peacemakers brought the effects of war home by shar- ing their ideas and experi- ences in an effort to encourage people to fight for peace. Almost 100 people gath- ered at La Fetra Auditorium on March 23 for the peace forum, “Practicing Nonvio- lence Amidst War and Conflict.” “This is a way to honor and bring attention to people who have spent their lives trying to bring people together,” said Tripp Mikich, coordinator of the event. The forum included several keynote speakers including Mark Manning, Sarah Holewinski, Dr. Waquar Al- Kubaisy, Le Ly Hayslip, Michael Nagler, and Claude Anshin Thomas. The audience sat in silence as filmmaker Mark Manning introduced the short film, “Caught in the Crossfire: The Untold Story of Falluja.” Lindsey Gooding Gasps filled the air as Tatyana Kennedy, 3, enjoys blowing bubbles at the seventh annual dren participated in various activities, in an effort to teach children images flashed across the Gardenfest, hosted by La Verne Parks and Community Services how plants grow. The event was held at the Hillcrest Homes screen. The audience covered Department and the Hillcrest Homes community. Parents and chil- Saturday morning. their mouths in shock as and watched intently as they grew as he toured the children the plots, reminding the senior women and children ran in disappeared in the air. around the garden plots. David citizens of the citrus groves that panic as explosions destroyed Gardenfest “She loved planting the Stroup displayed his garden of once inhabited the Hillcrest their homes. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

Nightlife, Djing, and the Rise of Digital DJ Technologies a Dissertatio

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Turning the Tables: Nightlife, DJing, and the Rise of Digital DJ Technologies A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Kate R. Levitt Committee in Charge: Professor Chandra Mukerji, Chair Professor Fernando Dominguez Rubio Professor Kelly Gates Professor Christo Sims Professor Timothy D. Taylor Professor K. Wayne Yang 2016 Copyright Kate R. Levitt, 2016 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Kate R. Levitt is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii DEDICATION For my family iv TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE……………………………………………………………….........iii DEDICATION……………………………………………………………………….......iv TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………...v LIST OF IMAGES………………………………………………………………….......vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………….viii VITA……………………………………………………………………………………...xii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION……………………………………………...xiii Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..1 Methodologies………………………………………………………………….11 On Music, Technology, Culture………………………………………….......17 Overview of Dissertation………………………………………………….......24 Chapter One: The Freaks -

Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.Father of Australian Rock

Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.father of Australian rock Paul Oldham Supervisor: Dr Vicki Crowley A thesis submitted to The University of South Australia Bachelor of Arts (Honours) School of Communication, International Studies and Languages Division of Education, Arts, and Social Science Contents Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.father of Australian rock ................................................. i Contents ................................................................................................................................... ii Table of Figures ................................................................................................................... iv Abstract .................................................................................................................................. ivi Statement of Authorship ............................................................................................... viiiii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. ix Chapter One: Overture ....................................................................................................... 1 Introduction: Lobby Loyde 1941 - 2007 ....................................................................... 2 It is written: The dominant narrative of Australian rock formation...................... 4 Oz Rock, Billy Thorpe and AC/DC ............................................................................... 7 Private eye: Looking for Lobby Loyde ......................................................................... -

The Transgender-Industrial Complex

The Transgender-Industrial Complex THE TRANSGENDER– INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX Scott Howard Antelope Hill Publishing Copyright © 2020 Scott Howard First printing 2020. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, besides select portions for quotation, without the consent of its author. Cover art by sswifty Edited by Margaret Bauer The author can be contacted at [email protected] Twitter: @HottScottHoward The publisher can be contacted at Antelopehillpublishing.com Paperback ISBN: 978-1-953730-41-1 ebook ISBN: 978-1-953730-42-8 “It’s the rush that the cockroaches get at the end of the world.” -Every Time I Die, “Ebolarama” Contents Introduction 1. All My Friends Are Going Trans 2. The Gaslight Anthem 3. Sex (Education) as a Weapon 4. Drag Me to Hell 5. The She-Male Gaze 6. What’s Love Got to Do With It? 7. Climate of Queer 8. Transforming Our World 9. Case Studies: Ireland and South Africa 10. Networks and Frameworks 11. Boas Constrictor 12. The Emperor’s New Penis 13. TERF Wars 14. Case Study: Cruel Britannia 15. Men Are From Mars, Women Have a Penis 16. Transgender, Inc. 17. Gross Domestic Products 18. Trans America: World Police 19. 50 Shades of Gay, Starring the United Nations Conclusion Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Introduction “Men who get their periods are men. Men who get pregnant and give birth are men.” The official American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Twitter account November 19th, 2019 At this point, it is safe to say that we are through the looking glass. The volume at which all things “trans” -

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" Vinyl Single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE in the MOVIES Dr

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" vinyl single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE IN THE MOVIES Dr. Hook EMI 7" vinyl single CP 11706 1978-05-22 P COUNT ON ME Jefferson Starship RCA 7" vinyl single 103070 1978-05-22 P THE STRANGER Billy Joel CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222406 1978-05-22 P YANKEE DOODLE DANDY Paul Jabara AST 7" vinyl single NB 005 1978-05-22 P BABY HOLD ON Eddie Money CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222383 1978-05-22 P RIVERS OF BABYLON Boney M WEA 7" vinyl single 45-1872 1978-05-22 P WEREWOLVES OF LONDON Warren Zevon WEA 7" vinyl single E 45472 1978-05-22 P BAT OUT OF HELL Meat Loaf CBS 7" vinyl single ES 280 1978-05-22 P THIS TIME I'M IN IT FOR LOVE Player POL 7" vinyl single 6078 902 1978-05-22 P TWO DOORS DOWN Dolly Parton RCA 7" vinyl single 103100 1978-05-22 P MR. BLUE SKY Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) FES 7" vinyl single K 7039 1978-05-22 P HEY LORD, DON'T ASK ME QUESTIONS Graham Parker & the Rumour POL 7" vinyl single 6059 199 1978-05-22 P DUST IN THE WIND Kansas CBS 7" vinyl single ES 278 1978-05-22 P SORRY, I'M A LADY Baccara RCA 7" vinyl single 102991 1978-05-22 P WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH Jon English POL 7" vinyl single 2079 121 1978-05-22 P I WAS ONLY JOKING Rod Stewart WEA 7" vinyl single WB 6865 1978-05-22 P MATCHSTALK MEN AND MATCHTALK CATS AND DOGS Brian and Michael AST 7" vinyl single AP 1961 1978-05-22 P IT'S SO EASY Linda Ronstadt WEA 7" vinyl single EF 90042 1978-05-22 P HERE AM I Bonnie Tyler RCA 7" vinyl single 1031126 1978-05-22 P IMAGINATION Marcia Hines POL 7" vinyl single MS 513 1978-05-29 P BBBBBBBBBBBBBOOGIE -

DJ Playlist.Djp

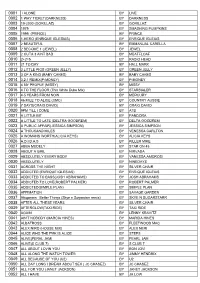

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

Garbage & the Temper Trap Join for Next Winery Series!

Media Release – Thursday July 28 GARBAGE & THE TEMPER TRAP JOIN FOR NEXT WINERY SERIES! With the Preatures, Tash Sultana and Adalita a day on the green has assembled an epic line-up for its next series of winery concerts. Alt-rock pioneers Garbage and Australia’s own multi-platinum chart toppers The Temper Trap will come together as part of their respective national tours for five outdoor events through November/December. The concerts will feature a stellar under-card with special guests The Preatures, Tash Sultana and Adalita. The five band bill kicks off at Victoria’s Rochford Wines on Saturday November 26. These will be the Garbage’s first Australian shows since 2013 and celebrate their acclaimed sixth studio album Strange Little Birds (out now via Liberator Music). To create Strange Little Birds, their first album in four years, Garbage (Shirley Manson, Steve Marker, Duke Erikson and Butch Vig) drew on a variety of influences including the albums they loved growing up. Upon its June release, the album debuted at #9 on the ARIA Album Chart and picked up widespread acclaim: ‘20-plus years after forming, each band member is still fired up to mine new sounds and approaches for inspiration. That willingness to be uncomfortable and look beneath the surface makes Strange Little Birds a rousing success.’ – The A.V. Club ‘The electronic rockers return with a sixth studio album as cool and caustic as their 1995 debut’ – NME ‘Garbage haven’t released an album this immediate, melodically strong and thematically interesting since their self-titled 1995 debut.’ – Mojo In support of the album’s release, Garbage performed a powerful two-song performance on Jimmy Kimmel Live! – watch ‘Empty’ here and ‘Push It’ here. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent. -

![KUCI 88.9 FM [Spring 1991]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0742/kuci-88-9-fm-spring-1991-1230742.webp)

KUCI 88.9 FM [Spring 1991]

· ..... ~ , ·I ••• · . ....... ~,,\, . ) - . \ -' (X) ~ I, (X) ,N • -0/--- co • • • • • - ~ . 1'" ~ I . .,I/:..~ . a:: . .", • •· ·, ·• I ·t'· . .• ·· . ·· . .. •••• i ,,".' . .. /' • Day of Decency has come and' gone. It has been months since a couple of heads got together on the 3rd floor of gateway commons and decided what part they would play in a battle for what they thought was right. And nearly a month (perhaps two as you read this) since the dreams and the plan came together. OUtcome? Well. for one, I'm not really sure. I'dreallylike tothink that maybesome part of Meye opening" or MreactionaryseDiment" ocurred on account ofsomeone standingup and screaming MMy rights as a citizen are in danger." Jlut how can something like that be measured? To tell you the truth, I don't know, either. I wish I had played my part out. AJJ the decision to ban Minde~ency", "profanity", and "obcenity" from public radio stations 24 hours a day is being appealed. we must watch, not wait, and act. How? You can call 866-6868 and find out. Anyone of the folks on staff has' access to the information. any day of the week, at any time. Provided, of course, there is someone here (ahem!). We can give you names and addre~ses. fax and phone numb,..rs of organizations and individuals who need the assistance of people like yourself, or in some cases, would, and do, defy ~our opposition. AJJ someone who values creativity and its limitless bounds, and wonders at the different kinds of reactions it provi-ies. from rage to confusion to recognition, it Is important for me to posess the ability to think freely.