Sagebrush Sparrow Artemisiospiza Nevadensis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

A Comprehensive Multilocus Assessment of Sparrow (Aves: Passerellidae) Relationships ⇑ John Klicka A, , F

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 77 (2014) 177–182 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Short Communication A comprehensive multilocus assessment of sparrow (Aves: Passerellidae) relationships ⇑ John Klicka a, , F. Keith Barker b,c, Kevin J. Burns d, Scott M. Lanyon b, Irby J. Lovette e, Jaime A. Chaves f,g, Robert W. Bryson Jr. a a Department of Biology and Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, Box 353010, Seattle, WA 98195-3010, USA b Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior, University of Minnesota, 100 Ecology Building, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA c Bell Museum of Natural History, University of Minnesota, 100 Ecology Building, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA d Department of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182, USA e Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14950, USA f Department of Biology, University of Miami, 1301 Memorial Drive, Coral Gables, FL 33146, USA g Universidad San Francisco de Quito, USFQ, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, y Extensión Galápagos, Campus Cumbayá, Casilla Postal 17-1200-841, Quito, Ecuador article info abstract Article history: The New World sparrows (Emberizidae) are among the best known of songbird groups and have long- Received 6 November 2013 been recognized as one of the prominent components of the New World nine-primaried oscine assem- Revised 16 April 2014 blage. Despite receiving much attention from taxonomists over the years, and only recently using molec- Accepted 21 April 2014 ular methods, was a ‘‘core’’ sparrow clade established allowing the reconstruction of a phylogenetic Available online 30 April 2014 hypothesis that includes the full sampling of sparrow species diversity. -

Artificial Water Catchments Influence Wildlife Distribution in the Mojave

The Journal of Wildlife Management; DOI: 10.1002/jwmg.21654 Research Article Artificial Water Catchments Influence Wildlife Distribution in the Mojave Desert LINDSEY N. RICH,1,2 Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California- Berkeley, 130 Mulford Hall 3114, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA STEVEN R. BEISSINGER, Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California- Berkeley, 130 Mulford Hall 3114, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA JUSTIN S. BRASHARES, Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California- Berkeley, 130 Mulford Hall 3114, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA BRETT J. FURNAS, Wildlife Investigations Laboratory, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Rancho Cordova, CA 95670, USA ABSTRACT Water often limits the distribution and productivity of wildlife in arid environments. Consequently, resource managers have constructed artificial water catchments (AWCs) in deserts of the southwestern United States, assuming that additional free water benefits wildlife. We tested this assumption by using data from acoustic and camera trap surveys to determine whether AWCs influenced the distributions of terrestrial mammals (>0.5 kg), birds, and bats in the Mojave Desert, California, USA. We sampled 200 sites in 2016–2017 using camera traps and acoustic recording units, 52 of which had AWCs. We identified detections to the species-level, and modeled occupancy for each of the 44 species of wildlife photographed or recorded. Artificial water catchments explained spatial variation in occupancy for 8 terrestrial mammals, 4 bats, and 18 bird species. Occupancy of 18 species was strongly and positively associated with AWCs, whereas 1 species (i.e., horned lark [Eremophila alpestris]) was negatively associated. Access to an AWC had a larger influence on species’ distributions than precipitation and slope and was nearly as influential as temperature. -

Guidelines for Finding Nests of Passerine Birds in Tallgrass Prairie

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center US Geological Survey 7-13-2003 Guidelines for Finding Nests of Passerine Birds in Tallgrass Prairie Maiken Winter State University of New York Shawn E. Hawks University of Minnesota - Crookston Jill A. Shaffer USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Douglas H. Johnson USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Winter, Maiken; Hawks, Shawn E.; Shaffer, Jill A.; and Johnson, Douglas H., "Guidelines for Finding Nests of Passerine Birds in Tallgrass Prairie" (2003). USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 160. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc/160 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in The Prairie Naturalist 35(3): September 2003. Published by the Great Plains Natural Science Society http://www.fhsu.edu/biology/pn/prairienat.htm Guidelines for Finding Nests of Passerine Birds in Tallgrass Prairie MAIKEN WINTER!, SHAWN E. HAWKS2, JILL A. SHAFFER, and DOUGLAS H. JOHNSON State University of New York, College of Environmental Sciences and Forestry, 1 Forestry Drive, Syracuse, NY 13210 (MW) University of Minnesota, Crookston, MN 58105 (SEH) U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, 8711 37th St. SE, Jamestown, ND 5840 I (lAS, DHJ) ABSTRACT -- The productivity of birds is one of the most critical components of their natural history affected by habitat quality. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

Integrating Birds Into Sagebrush Management Version 1

Integrating Birds into Sagebrush Management Version 1 Acknowledgements Contributors: Scott Gillihan, Laura Quattrini, Nick VanLanen, David Pavlacky, Gillian Bee. Reviewers: Terrell Rich, Marcella Fremgen, Pat Diebert, Thad Heater, Ashley-Anne Dayer Funding: Natural Resources Conservation Service – Conservation Innovation Grant www.nrcs.usda.gov/technical/cig Western Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education – Professional Development www.westernsare.org National Fish and Wildlife Foundation http://www.nfwf.org/ Purpose The sagebrush sea is a critical landscape in North America in that it provides vital ecological, hydrological, biological, agricultural, and recreational ecosystem services and is managed for equally diverse uses (Homer et al 2015). Several birds (Appendix A) found in this landscape are termed ‘sagebrush obligate’ (i.e. sage-grouse, Sagebrush Sparrow, Sage Thrasher) and rely upon the sagebrush ecosystem for their survival. Integrating birds into land management decisions on public and private land can lead to win-win results for land manager, wildlife and other natural resources. Thus, conservation practitioners should work cooperatively and pro-actively for seamless (cross-boundary), large-scale conservation of birds and their habitats. This manual provides general information about the sagebrush ecosystem, its relationship with bird communities, and habitat requirements and conservation measures for birds typically found within habitats of the eastern range of the sagebrush footprint. While tools to help guide land management decisions to enhance decisions that foster a multi- species approach to conservation are described here, they are not meant to replace site-specific knowledge and goals (Knapp and Fernandez-Gimenez 2008; Davis and Wagner 2003) gained from long- term interactions with the land being managed. -

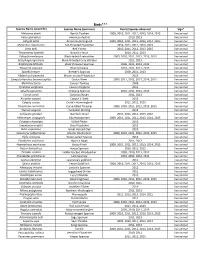

Flora and Fauna List.Xlsx

Birds*** Species Name (scientific) Species Name (common) Year(s) Species observed Sign* Melozone aberti Abert's Towhee 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Falco sparverius American Kestrel 2010, 2013 live animal Calypte anna Anna's Hummingbird 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Myiarchus cinerascens Ash‐throated Flycatcher 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Vireo bellii Bell's Vireo 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Thryomanes bewickii Bewick's Wren 2010, 2011, 2013 live animal Polioptila melanura Black‐tailed Gnatcatcher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Setophaga nigrescens Black‐throated Gray Warbler 2011, 2013 live animal Amphispiza bilineata Black‐throated Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Passerina caerulea Blue Grosbeak 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Spizella breweri Brewer's Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2013 live animal Myiarchus tryannulus Brown‐crested Flycatcher 2013 live animal Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus Cactus Wren 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Melozone fusca Canyon Towhee 2009 live animal Tyrannus vociferans Cassin's Kingbird 2011 live animal Spizella passerina Chipping Sparrow 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Corvus corax Common Raven 2011, 2013 live animal Accipiter cooperii Cooper's Hawk 2013 live animal Calypte costae Costa's Hummingbird 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Toxostoma curvirostre Curve‐billed Thrasher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Sturnus vulgaris European Starling 2012 live animal Callipepla gambelii Gambel's -

The Importance of Floristics to Sagebrush Breeding Birds of the South Okanagan and Similkameen Valleys, British Columbia1

The Importance of Floristics to Sagebrush Breeding Birds of the South Okanagan and Similkameen Valleys, British Columbia1 Susan Paczek2 and Pam Krannitz3 ________________________________________ Abstract Habitat associations were determined for five species species in Canada relative to the 3 percent of area that of songbirds breeding in sagebrush habitat of the South these habitat types occupy (Hooper and Pitt 1995). At Okanagan and Similkameen valleys, British Columbia. the northern extent of the Great Basin, the shrubsteppe We examined the relative importance of plant species habitat of the southern Okanagan and Similkameen versus “total forbs” and “total grasses” at a local level Valleys (fig. 1) supports many species that are at the (<100 m) with point counts and vegetation survey data limit of their range and are unique in Canada. This area collected at 245 points. Logistic regression models contains a high concentration of bird species at risk, showed that individual plant species were often more including provincially red-listed shrubsteppe birds such important than variables that grouped species. Habitat as Brewer's Sparrow (Spizella breweri breweri), Grass- associations varied for each species. Brewer's Sparrow hopper Sparrow (Ammodrammus savannarum) and (Spizella breweri) was associated with parsnip- Lark Sparrow (Chondestes grammacus). In addition, flowered buckwheat (Eriogonum heracleoides) and North American Breeding Bird Survey data compiled lupine (Lupinus sericeus or sulphureus). Lark Sparrow for the period 1966 to 1996 showed significant con- (Chondestes grammacus) was positively associated tinental decreases in populations of Brewer's Sparrow, with sand dropseed grass (Sporobolus cryptandrus), Lark Sparrow, Grasshopper Sparrows and Western Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodrammus savannarum) Meadowlarks (Sturnella neglecta; Peterjohn and Sauer was positively associated with pasture sage (Artemisia 1999), all of which breed in the study area. -

The Great Sagebrush Sparrow Hunt

The Great Sagebrush Sparrow Hunt Kimball L. Garrett Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County With a big assist from Andy Birch, who provided his artwork and in-depth research on the field identification of Sagebrush and Bell’s Sparrows “Sage Sparrow” plate by Allan Brooks from Dawson’s Birds of California General Outline History of the species and subspecies Current taxonomy Phenotypic traits [“field marks”] of the subject taxa Genetic studies of the main groups Vocalizations of the groups Status in Los Angeles County and vicinity Bell’s Sparrow (belli, canescens, clementeae) Sagebrush Sparrow Where, how to search for Sagebrush Sparrows Undiagnosable? A distinct species? Or something inbetween? Piute Ponds, L. A. Co. 10 Nov 2020 Larry Sansone Summary of taxonomic history Emberiza belli J. Cassin, 1850 (near Sonoma, CA) Poospiza bellii var. nevadensis R. Ridgway, 1874 (W. Humboldt Mtns., NV) Amphispiza belli cinerea C. H. Townsend, 1890 (Bahia de Ballenas, Baja CA) Amphispiza belli clementeae R. Ridgway, 1898 (San Clemente I., CA) Amphispiza belli canescens J. Grinnell, 1905 (Mt. Pinos, Ventura Co., CA) Not currently recognized: Amphispiza belli campicola Oberholser (n. range of nevadensis) Amphispiza belli xerophilus (Baja, between ranges of belli and cinerea) Treatment by the AOU Check-lists and Supplements 1st ed. (1886) Amphispiza belli [no trinomials used in this edition] Amphispiza belli nevadensis 2nd ed. (1895) Amphispiza belli [no trinomials used in this edition] Amphispiza belli nevadensis (Great Basin) Amphispiza belli cinerea (Lower CA) 3rd ed. (1910) Amphispiza belli Amphispiza nevadensis nevadensis Amphispiza nevadensis cinerea (Lower CA) Amphispiza nevadensis canescens 4th ed. (1931) Amphispiza belli belli “Bell’s Sparrow” Amphispiza belli cinerea “Gray Sage Sparrow” Amphispiza nevadensis nevadensis “Northern Sage Sparrow” Amphispiza nevadensis canescens “California Sage Sparrow” Treatment by the AOU Check-lists and Supplements 5th ed. -

NEWS and NOTES by Paul Hess

NEWS AND NOTES by Paul Hess “Lilian’s” Meadowlark für Ornithologie 135:28), but no details about the findings have been published. Ornithologist Harry C. Oberholser was intrigued by mead - At last, a large-scale genetic report by F. Keith Barker, Ar - owlarks collected in 1929 near Arizona’s Huachuca Moun - ion J. Vandergon, and Scott M. Lanyon arrived in 2008 tains, because their size, structure, and plumage differed (Auk 125:869–879). They examined two mitochondrial from those of the Western Meadowlark and from known DNA (mtDNA) genes and one nuclear locus in 14 Eastern variations of Eastern Meadowlark. In 1930 he described the Meadowlark subspecies throughout the North American, specimens as a new Eastern Meadowlark subspecies and Central American, and South American range. named it lilianae to honor Lilian Baldwin, who had donat - The results indicate a long history of evolutionary diver - ed the collection ( Scientific Publications of the Cleveland Mu - gence between lilianae and all except one other Eastern seum of Natural History 1:83–124). Meadowlark subspecies, auropectoralis of central and We now know it as “Lilian’s” Meadowlark, of desert grasslands in the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico, where it is distinguishable from Western Meadowlark with careful study by eye and ear. In identification guides, lilianae re - ceived little attention and no illustration until the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America in 1983. Kevin J. Zimmer of - fered tips in Birding (August 1984, pp. 155–156) and in his books The Western Bird Watcher (Prentice-Hall 1985) and Birding in the American West (Cornell University Press 2000). -

Rationales for Animal Species Considered for Designation As Species of Conservation Concern Inyo National Forest

Rationales for Animal Species Considered for Designation as Species of Conservation Concern Inyo National Forest Prepared by: Wildlife Biologists and Natural Resources Specialist Regional Office, Inyo National Forest, and Washington Office Enterprise Program for: Inyo National Forest August 2018 1 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992.