Buffy Conquers the Academy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Edition

2012 Edition Cleveland State Community College ENGLISH DEPARTMENT Editor: Julie Fulbright Assistant Editor: Heather Cline Liner Front cover photography by: Amanda Guffey Graphic Design and Production: CSCC Marketing Department Printer: Dockins Graphics, Cleveland, Tenn. Copyright: 2012 Cleveland State Community College www.clevelandstatecc.edu All Rights Reserved Funding for this publication provided under Title I of the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act of 2006. CSCC HUM/12095/04092012 - Cleveland State Community College is an AA/ EEO employer and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, disability or age in its program and activities. The following department has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the non-discrimination policies: Human Resources P.O. Box 3570 Cleveland, TN 37320-3570 [email protected] Table of Contents Written By Title Photo/Drawing By: Page Frankie Conar After the Storm Julie Fulbright 5 Brittney Glover Weep for Me James Loyless 6 Leaves of the Sea Amanda Guffey 7 Stormy Fisher Mother 8 Savannah Tioaquen I Am the Wind Brandon Perry 9 Tracey Thompson Rose Amanda Guffey 10 Mirror Mirror Megan Payne 11 Tonya Arsenault Siblings Marchelle Wear 12-13 We Can’t Go Back in Time Kimberley Stewart 14-15 Angel Jadoobirsingh Spying Angel Jadoobirsingh 16 My Pay Angel Crawford 17 Cody Thrift Through Solemn Eyes Misti Stoika 18 I Had a Dream I Died Alonzo Bell 19-20 The Hero Tonya Arsenault 21-22 Nicholas Johnson Such Is Life Angel Jadoobirsingh 23 Turn the Lights Out 24 The Window by the Tree Marchelle Wear 25 Chet Guthrie Christmas on the Battlefield Amanda Guffey 26-29 Sweet Kalan Tonya Arsenault 30-34 The 23rd Psalm Marchelle Wear 35-37 Letters through the Fence Marchelle Wear 38-42 Grandfather’s Axe Marchelle Wear 43-44 Her Beauty Daniel Stokes 45 In the Eyes of a Dreamer Megan Payne 46 Rise o’ Rise Dear Wall Street 47 The Old Man Michael Espinoza 48 A Night of Passion Shanna Calfee 49-50 Table of Contents - Cont’d. -

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season 9 Volume 4: Welcome to the Team Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER SEASON 9 VOLUME 4: WELCOME TO THE TEAM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andrew Chambliss,Sierra Hahn,Scott Allie,Karl Moline,Andy Owens,Georges Jeanty,Dexter Vines | 168 pages | 08 Oct 2013 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616551667 | English | Milwaukee, United States Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season 9 Volume 4: Welcome to the Team PDF Book The fourth season averaged 5. January 26, [34]. I should point out, that I don't really care for the Zompires or the side story, featuring the first Male slayer. The moai later fuse into a stone giant which attacks Spike and Morgan. About Andrew Chambliss. Willow falls in love with Tara Maclay , another witch. Maybe allow is the wrong word, but you get what I mean. September 18, [30]. Contner ; and "Restless" by writer and director Joss Whedon. I also feel like his art is regressing some, especially when it comes to drawing characters to a recognizable likeness to the show. Lavinia and Sophronia take credit in front of the media for stopping the crisis. Then again, maybe that's what she wants, no respite. All-in- all, I love this installment of the Buffyverse. How was your experience with this page? Willow, Tara, and Giles perform a spell to stop the spirits. Retrieved July 30, Because vampires are immune to Eyghon's ability to possess the dead and unconscious, with which he plans to build an army of Slayers, Angel recruits Spike to assist him on a mission to kill the demon. Jan 13, Jack rated it it was amazing. Nov 21, Kristine The Writer's Inkwell rated it liked it Shelves: comics , reading-challenge , buffy-the-vampire-slayer. -

Moroni: Angel Or Treasure Guardian? 39

Mark Ashurst-McGee: Moroni: Angel or Treasure Guardian? 39 Moroni: Angel or Treasure Guardian? Mark Ashurst-McGee Over the last two decades, historians have reconsidered the origins of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the context of the early American tradition of treasure hunting. Well into the nineteenth century there were European Americans hunting for buried wealth. Some believed in treasures that were protected by magic spells or guarded by preternatural beings. Joseph Smith, founding prophet of the Church, had participated in several treasure-hunting expeditions in his youth. The church that he later founded rested to a great degree on his claim that an angel named Moroni had appeared to him in 1823 and showed him the location of an ancient scriptural record akin to the Bible, which was inscribed on metal tablets that looked like gold. After four years, Moroni allowed Smith to recover these “golden plates” and translate their characters into English. It was from Smith’s published translation—the Book of Mormon—that members of the fledgling church became known as “Mormons.” For historians of Mormonism who have treated the golden plates as treasure, Moroni has become a treasure guardian. In this essay, I argue for the historical validity of the traditional understanding of Moroni as an angel. In May of 1985, a letter to the editor of the Salt Lake Tribune posed this question: “In keeping with the true spirit (no pun intended) of historical facts, should not the angel Moroni atop the Mormon Temple be replaced with a white salamander?”1 Of course, the pun was intended. -

Read Book Dear Boy, : a Celebration of Cool, Clever, Compassionate You!

DEAR BOY, : A CELEBRATION OF COOL, CLEVER, COMPASSIONATE YOU! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paris Rosenthal | 40 pages | 23 Apr 2019 | HarperCollins | 9780062422514 | English | none Dear Boy, : A Celebration of Cool, Clever, Compassionate You! PDF Book If you order a book by phone or through our website, we will let you know when it is ready for pick-up at the door. Error loading page. Toys for Men Toys for Seniors. Nevertheless, we hope to make your Christmas and Hanukkah shopping as stress-free as possible! Add more details:. Check here for more details. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. This second Big Nate themed activity book is bursting with Parents' Ultimate Guide to Learn how we rate. Add a card Contact support Cancel. We will reach out to you as soon as possible. Your Email. More titles may be available to you. You can vote multiple times per day. See all 29 - All listings for this product. Where are the books for little boys? Related Deals. Books That Teach Empathy. Sign in to see the full collection. Add to Cart - Letters Only. Show More Show Less. Juvenile Fiction Juvenile Literature. Buy It Now. Dear Boy, : A Celebration of Cool, Clever, Compassionate You! Writer See all 29 - All listings for this product. Product categories. Any Condition Any Condition. The OverDrive Read format of this ebook has professional narration that plays while you read in your browser. The parents' guide to what's in this book. Developmental Goals. OverDrive Listen audiobook MP3 audiobook. We will reach out to you as soon as possible. -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

“The Wounded Angel Considers the Uses of So-Called Secular Literature to Convey Illuminations of Mystery, the Unsayable, the Hidden Otherness, the Holy One

“The Wounded Angel considers the uses of so-called secular literature to convey illuminations of mystery, the unsayable, the hidden otherness, the Holy One. Saint Ignatius urged us to find God in all things, and Paul Lakeland demonstrates how that’s theologically possible in fictions whose authors had no spiritual or religious intentions. A fine and much-needed reflection.” — Ron Hansen Santa Clara University “Renowned ecclesiologist Paul Lakeland explores in depth one of his earliest but perduring interests: the impact of reading serious modern fiction. He convincingly argues for an inner link between faith and religious imagination. Drawing on a copious cross section of thoughtful novels (not all of them ‘edifying’), he reasons that the joy of reading is more than entertainment but rather potentially salvific transformation of our capacity to love and be loved. Art may accomplish what religion does not always achieve. The numerous titles discussed here belong on one’s must-read list!” — Michael A. Fahey, SJ Fairfield University “Paul Lakeland claims that ‘the work of the creative artist is always somehow bumping against the transcendent.’ What a lovely thought and what a perfect summary of the subtle and significant argument made in The Wounded Angel. Gracefully moving between theology and literature, religious content and narrative form, Lakeland reminds us both of how imaginative faith is and of how imbued with mystery and grace literature is. Lakeland’s range of interests—Coleridge and Louise Penny, Marilynne Robinson and Shusaku Endo—is wide, and his ability to trace connections between these texts and relate them to large-scale theological questions is impressive. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

S H a P E S O F a P O C a Ly P

Shapes of Apocalypse Arts and Philosophy in Slavic Thought M y t h s a n d ta b o o s i n R u s s i a n C u lt u R e Series Editor: Alyssa DinegA gillespie—University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana Editorial Board: eliot Borenstein—New York University, New York Julia BekmAn ChadagA—Macalester College, St. Paul, Minnesota nancy ConDee—University of Pittsburg, Pittsburg Caryl emerson—Princeton University, Princeton Bernice glAtzer rosenthAl—Fordham University, New York marcus levitt—USC, Los Angeles Alex Martin—University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana irene Masing-DeliC—Ohio State University, Columbus Joe pesChio—University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee irina reyfmAn—Columbia University, New York stephanie SanDler—Harvard University, Cambridge Shapes of Apocalypse Arts and Philosophy in Slavic Thought Edited by Andrea OppO BOSTON / 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A bibliographic record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-61811-174-6 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-618111-968 (electronic) Book design by Ivan Grave On the cover: Konstantin Juon, “The New Planet,” 1921. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. -

The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 2010 "Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Burnett, Tamy, ""Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 by Tamy Burnett A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Specialization: Women‟s and Gender Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Kwakiutl L. Dreher Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Kwakiutl L. Dreher Found in the most recent group of cult heroines on television, community- centered cult heroines share two key characteristics. The first is their youth and the related coming-of-age narratives that result. -

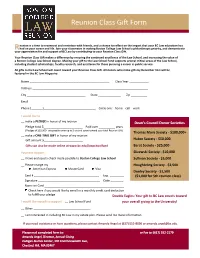

Reunion Class Gift Form

Reunion Class Gift Form eunion is a time to reconnect and reminisce with friends, and a chance to reflect on the impact that your BC Law education has R had on your career and life. Join your classmates in making Boston College Law School a philanthropic priority, and demonstrate your appreciation for and support of BC Law by contributing to your Reunion Class Gift. Your Reunion Class Gift makes a difference by ensuring the continued excellence of the Law School, and increasing the value of a Boston College Law School degree. Making your gift to the Law School Fund supports several critical areas of the Law School, including student scholarships, faculty research, and assistance for those pursuing a career in public service. All gifts to the Law School will count toward your Reunion Class Gift. All donors who make gifts by December 31st will be featured in the BC Law Magazine. Name _________________________________________________ Class Year ____________ Address _______________________________________________________________________ City ____________________________________ State ______________ Zip __________ Email _________________________________________________________________________ Phone (_______)________________________________ Circle one: home cell work I would like to __ make a PLEDGE in honor of my reunion Dean’s Council Donor Societies Pledge total $________________________ Paid over __________ years (Pledges of $10,000+ are payable over up to 5 yrs and count toward your total Reunion Gift) Thomas More Society - $100,000+ __ make a ONE-TIME GIFT in honor of my reunion Huber Society - $50,000 Gift amount $________________________ Gifts can also be made online at www.bc.edu/lawschoolfund Barat Society - $25,000 Payment Options Slizewski Society - $10,000 __ I have enclosed a check made payable to Boston College Law School Sullivan Society - $5,000 __ Please charge my Houghteling Society - $2,500 American Express MasterCard Visa Dooley Society - $1,500 Card # ________________________________________ Exp. -

THE WONDERFUL APPEARANCE of an Angel, Devil & Ghost, to a GENTLEMAN in the Town of Boston, in the Nights of the 14Th, 15Th, and 16Th of October, 1774" (Boston, 1774)

National Humanities Center My Neighbor, My Enemy: How American Colonists Became Patriots and Loyalists "THE WONDERFUL APPEARANCE of an Angel, Devil & Ghost, to a GENTLEMAN in the Town of Boston, In the Nights of the 14th, 15th, and 16th of October, 1774" (Boston, 1774) A little known political document, "The Wonderful Appearance" is sort of a colonial American version of A Christmas Carol in which three apparitions try to convert a sinner. It was published in Boston in the summer of 1774, the moment of greatest popular rage against royal officials in Massachusetts. It asked the ordinary reader to consider carefully what might happen to someone who tried to remain neutral—or worse, gave comfort to the enemy—during a revolutionary crisis. Although the story contains marvelous humor, it reminds us of the pressure a community could bring to bear on enemies and skeptics. The narrator, who sympathizes with the British, returns to his room after a supper with some jovial companions and is struck by terror when he hears an awful sound nearby. The noise continues until a "violent wrap against" his window signals the entrance of an angel, who pulls up a chair and delivers two messages. First, the angel says, if the narrator does not cease to oppress his countrymen, he will end up in hell. Second, the Devil is going to drop by tomorrow night to tell him so in person. Like Scrooge, the narrator tries to convince himself that his first nocturnal visitor was merely a delusion, but he never quite succeeds. The next night, as predicted, the Devil—a rational, cool- headed gentleman—appears and asks the narrator how he became such an enemy to his country. -

Amends Script

Amends (October 31, 1998) Written by: Joss Whedon Teaser EXT. DUBLIN STREET - NIGHT (1838) A Dickensian vista of Christmas. Snow covers the street (though it is not falling now), people and carriages milling about in it. A group of five or so CAROLLERS stand by one corner, singing a traditional Christmas air. A young man (DANIEL) in a dark suit makes his way through the people, quickly and nervously. He looks about him constantly. He passes an alley and he is suddenly GRABBED and pulled inside. He lands in a heap in the corner, the figure that grabbed him standing over him. ANGEL Why, Daniel, wherever are you going? Angel is dressed similarly -- though a bit more elegantly -- to Daniel. He is smiling graciously, and in full vampface. Daniel cowers, scrambling backwards. DANIEL You -- you're not human... ANGEL Not of late, no. DANIEL What do you want? ANGEL Well, it happens that I'm hungry, Daniel, and seeing as you're somewhat in my debt... DANIEL Please... I can't... ANGEL A man playing at cards should have a natural intelligence or a great deal of money and you're sadly lacking in both. So I'll take my winnings my own way. He grabs him, hoists him up. Daniel cannot wrest Angel's grasp from his throat. He Buffy Angel Show babbles quietly: DANIEL The lord is my shepherd, I shall not want... he maketh me to lie down in green pastures... he... ANGEL Daniel. Be of good cheer. (smiling) It's Christmas! He bites. INT. MANSION - ANGEL'S BEDROOM - NIGHT Angel awakens in a start, sweating.