1 Chapter 10 the North and Europe in 24 Hour Party People and Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the High Court of Justice Claim No Hc13 Fo4688 Chancery Division Intellectual Property Between

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE CLAIM NO HC13 FO4688 CHANCERY DIVISION INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY BETWEEN; WARNER RECORDS 90 LIMITED STEPHEN MORRIS GILLIAN GILBERT BERNARD SUMNER DEBORAH WOODRUFF PETER HOOK - and - JULIA ADAMSON D E F E N C E OF JULIA ADAMSON DEFENDANT Clauses 9 (a) and (b), 21, 22, 23, 24 I was an employee at Strawberry Studios from 1984 to 1989. When Strawberry Studios closed down the staff were busy clearing out the building. There were at least 20,000 copy masters from various bands and the artistes or their agents. They were contacted as to whether they wished to buy the tapes from the Strawberry library because they were clearing out. Mostly the artistes already had their own copies and said Strawberry should dispose of them. Some asked for the copy masters and these were handed over. The remaining copy masters were consigned to the skips. A colleague David Drennan was assigned the task of contacting as many of the clients as possible about their tapes. In the case of Factory Records, David Drennan remembers that they only asked for The Happy Mondays tapes and did not want any others. (see copy email ‘Dave Drennan’) Later I discovered that Factory Records had parted company with Joy Division/New Order. I felt that the tapes of Martin Hannett's work i.e. the ones he produced should not be destroyed. That is why I removed them from the skip and rescued them from landfill. When Warners were threatening court action I contacted Nick Turnbull (see copy email ‘Nick Turnbull’) who had been the owner of Strawberry Studios and who closed it down. -

Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository August 2016 Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E. Morley The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts © Briana E. Morley 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Morley, Briana E., "Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3991. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3991 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Abstract There is a dark mythology surrounding the post-punk band Joy Division that tends to foreground the personal history of lead singer Ian Curtis. However, when evaluating the construction of Joy Division’s public image, the contributions of several other important figures must be addressed. This thesis shifts focus onto the peripheral figures who played key roles in the construction and perpetuation of Joy Division’s image. The roles of graphic designer Peter Saville, of television presenter and Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, and of photographers Kevin Cummins and Anton Corbijn will stand as examples in this discussion of cultural intermediaries and collaborators in popular music. -

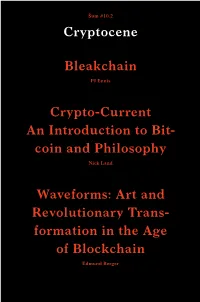

Coin and Philosophy Bleakchain Waveforms

Šum #10.2 Cryptocene Bleakchain PJ Ennis Crypto-Current An Introduction to Bit- coin and Philosophy Nick Land Waveforms: Art and Revolutionary Trans- formation in the Age of Blockchain Edmund Berger Šum #10.2 Cryptocene 1343 Partnerji in koproducenti Publikacija je nastala v okviru projekta State Machines, ki ga izvajajo Aksioma (SI), Drugo more (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) in NeMe (CY). Izvedba tega projekta je financirana Društvo s strani Evropske komisije. Vsebina komunikacije je izključno odgovornost avtorja in v nobenem primeru ne predstavlja stališč Evropske komisije. Galerija BOKS drustvoboks.wordpress.com Društvo Igor Zabel www.igorzabel.org Realized in the framework of State Machines, a joint project by Aksioma (SI), Drugo more (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) and NeMe (CY). Galerija Galerija This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission Kapelica Škuc cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. www.kapelica.org galerija.skuc-drustvo.si PartnerjiŠum in koproducenti#10.2 PartnerjiŠum in koproducenti#10.2 MGLC UGM Mednarodni grafični likovni center Umetnostna galerija Maribor www.ugm.si www.mglc-lj.si Mestna Zavod Celeia Celje galerija Ljubljana Center sodobnih umetnosti www.celeia.info www.mgml.si/ mestna-galerija-ljubljana MG+MSUM Aksioma OSMO/ZA Moderna galerija www.aksioma.org www.osmoza.si www.mg-lj.si 1346 1347 Šum #10.2 Šum #10.2 Bleakchain PJ Ennis 1349 Bleakchain PJ Ennis 1355 Crypto-Current An Introduction to Bitcoin and Philosophy nick Land 1373 Waveforms: Art and Revolutionary Transformation in the Age of Blockchain Edmund BErgEr The following is source material drawn from Tropical by PJ Ennis, a novel about the collapse of a post-cryptocurrency society in the thirty-first century. -

Strumenti Per La Didattica E La Ricerca

strumenti per la didattica e la ricerca – 94 – Brand-building: the creative city a critical look at current concepts and practices edited by serena Vicari Haddock Firenze university press 2010 Brand-building : the creative city : a critical look at current concepts and practices / a cura di serena Vicari Haddock. – Firenze : Firenze university press, 2010. (strumenti per la didattica e la ricerca ; 94) http://digital.casalini.it/9788884535405 isBn 978-88-8453-524-5 (print) isBn 978-88-8453-540-5 (online) cover illustration @ phil Haddock, city of Words, detail. the publication of this book was made possible by a financial contribution coming from the eu research training network: Urban Europe between Identity and Change (UrbEurope); contract nr: HPRN-CT-2002-00227 (01-09-2002 - 31-08-06), and from the EU coordina- tion action: Growing Inequality and Social Innovation: Alternative Knowledge and Practice in Overcoming Social Exclusion in Europe (Katarsis); contract nr: cit5-ct-2006-029044 (05-01- 2006 – 30-11-2009). progetto grafico di alberto pizarro Fernández © 2010 Firenze university press università degli studi di Firenze Firenze university press Borgo albizi, 28, 50122 Firenze, italy http://www.fupress.com/ Printed in Italy ContentsCapitolo Foreword 7 introduction 13 M. d’Ovidio, S. Vicari Haddock chapter 1 Branding the creative city 17 S. Vicari Haddock chapter 2 the creative city imaginary 39 A. Vanolo chapter 3 site-specificity and urban icons in the light of the creative city marketing 61 B. Springer chapter 4 creating a creative city: discussing the discourse that is transforming the city 83 J. Kulonpalo chapter 5 the city that Was creative and did not Know: manchester and popular music 1976-1997 95 G. -

9 SONGS-B+W-TOR

9 SONGS AFILMBYMICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM One summer, two people, eight bands, 9 Songs. Featuring exclusive live footage of Black Rebel Motorcycle Club The Von Bondies Elbow Primal Scream The Dandy Warhols Super Furry Animals Franz Ferdinand Michael Nyman “9 Songs” takes place in London in the autumn of 2003. Lisa, an American student in London for a year, meets Matt at a Black Rebel Motorcycle Club concert in Brixton. They fall in love. Explicit and intimate, 9 SONGS follows the course of their intense, passionate, highly sexual affair, as they make love, talk, go to concerts. And then part forever, when Lisa leaves to return to America. CAST Margo STILLEY AS LISA Kieran O’BRIEN AS MATT CREW DIRECTOR Michael WINTERBOTTOM DP Marcel ZYSKIND SOUND Stuart WILSON EDITORS Mat WHITECROSS / Michael WINTERBOTTOM SOUND EDITOR Joakim SUNDSTROM PRODUCERS Andrew EATON / Michael WINTERBOTTOM EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Andrew EATON ASSOCIATE PRODUCER Melissa PARMENTER PRODUCTION REVOLUTION FILMS ABOUT THE PRODUCTION IDEAS AND INSPIRATION Michael Winterbottom was initially inspired by acclaimed and controversial French author Michel Houellebecq’s sexually explicit novel “Platform” – “It’s a great book, full of explicit sex, and again I was thinking, how come books can do this but film, which is far better disposed to it, can’t?” The film is told in flashback. Matt, who is fascinated by Antarctica, is visiting the white continent and recalling his love affair with Lisa. In voice-over, he compares being in Antarctica to being ‘two people in a bed - claustrophobia and agoraphobia in the same place’. Images of ice and the never-ending Antarctic landscape are effectively cut in to shots of the crowded concerts. -

Peter Hook L’Haçienda La Meilleure Façon De Couler Un Club

PETER HOOK L’HAÇIENDA LA MEILLEURE FAÇON DE COULER UN CLUB LE MOT ET LE RESTE PETER HOOK L’HAÇIENDA la meilleure façon de couler un club traduction de jean-françois caro le mot et le reste 2020 Ce livre est dédié à ma mère, Irene Hook, avec tout mon amour Reposez en paix : Ian Curtis, Martin Hannett, Rob Gretton, Tony Wilson et Ruth Polsky, sans qui l’Haçienda n’aurait jamais été construite LES COUPABLES Bien sûr que ça me poserait problème. Lorsque Claude Flowers m’a suggéré en 2003 d’écrire mes mémoires sur l’Haçienda, la première chose qui me vint à l’esprit est cette célèbre citation au sujet des années soixante : si vous vous en souvenez, c’est que vous n’y étiez pas. Tel était mon sentiment au sujet de l’Haç. J’allais donc avoir besoin d’un peu d’aide, et ce livre est le fruit d’un effort collectif. Claude a lancé les hostilités et m’a invité à me replonger dans de très nombreux souvenirs que je pensais avoir oubliés, tandis qu’Andrew Holmes m’a fourni ces « interludes » essentielles tout en se chargeant des démarches administratives. Je m’attribue le mérite de tout ce qui vous plaira dans ce livre. Si des passages vous déplaisent, c’est à eux qu’il faudra en vouloir. Avant-propos Nous avons vraiment fait n’importe quoi. Vraiment ? À y repenser aujourd’hui, je me le demande. Nous sommes en 2009 et l’Haçienda n’a jamais été aussi célèbre. En revanche, elle ne rapporte toujours pas d’argent ; rien n’a changé de ce côté-là. -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

No Countryin Oscar Country

THE GA T EWAY volume XCVIII number 22 ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT 11 No Country in Oscar country his boots for blood or flips a coin, absolute best. filmreview the film becomes less about temper- If No Country For Old Men needs to ing the despair with a laugh and more be seen for any other reason than being No Country For Old Men about everything in us that is sick an adaptation of the work of a Pulitzer- Now Playing and wrong. The Coen brothers have winning author by a screenwriter/ Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen walked us down this road before, director duo in their absolute prime Starring Tommy Lee Jones, Javier but in this adaptation of the Cormac and with a stellar cast, it’s for Roger Bardem, Josh Brolin, Woody McCarthy novel, the view has never Deakins’ incredible cinematography: Harrelson, and Kelly MacDonald been so mesmerizing or austere. at times both wistfully spare and eerily No Country For Old Men is a re-hash- confined, every frame is essential to MAtt HUBERT ing of the wrong-place-at-the-wrong- developing the explosive interplay of Arts & Entertainment Staff time motif, somewhat displaced from Moss, Chigurh, and Bell. gunslinger times. It’s rural, dustbowl Moss and Chigurh’s country is one There’s something so wry and mer- Texas in 1980, and Llewelyn Moss where moral right and wrong is met rily morose about Anton Chigurh (Josh Brolin) stumbles upon a cache of with a measured indifference; one (Javier Bardem) that hordes of Coen drugs and $2 million after a drug deal does what one does simply because brothers faithful will be getting that gone wrong; like any good and sane he either wishes to or has no other warm, fuzzy feeling of familiarity opportunist, he takes the money and option. -

First Street Manchester One Two Three Four Five Six Seven Eight Nine Ten Contact One Two Three Four Five Six Seven Eight Nine Ten Contact First Street First

FIRST STREET MANCHESTER ONE TWO THREE FOUR FIVE SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE TEN CONTACT ONE TWO THREE FOUR FIVE SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE TEN CONTACT FIRST STREET FIRST Find yourself in First Street. An environment created for happiness and productivity where work and life intertwine. Breaking down boundaries between the personal and the professional, this is a community for contemporary working and living. ONE TWO THREE FOUR FIVE SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE TEN CONTACT FIRST STREET THE PLACE TO BE WHITWORTH STREET WEST FIRST STREET TONY WILSON PLACE MEDLOCK STREET ISABELLA BANKS ST. JAMES GRIGOR SQUARE NO.8 ONE TWO THREE FOUR FIVE SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE TEN CONTACT TONY WILSON PLACE At First Street Tony Wilson Place is named after the maverick Mancunian Tony Wilson, AKA ‘Mr Manchester’. DJ, Journalist, TV Presenter and more, his achievements are too many to mention. Tony famously founded the Hacienda nightclub and co-founded Factory Records. home to acts including Joy Division, New Order, Happy Mondays and James. Inspired by his spirit, Tony Wilson Place breathes new life into an old Manchester site (previously home to a gas works and also the British Council). Like Tony, it’s a place that understands the business benefits of culture, the arts and entertainment. ONE TWO THREE FOUR FIVE SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE TEN CONTACT IMPRESSIVE FIRST IMPRESSIONS Step into the recently refurbished and modernised reception. Along with the full height central atrium, it provides a wonderful welcome. The contemporary mood of your arrival experience is in keeping with the calibre of companies within the building. -

Iceland Airwaves: the Final Countdown B14 #1 and at All Major Tourist Attractions and Tourist Information Centres

Airwaves Special Mínus + Mr. Silla & Mongoose + Bloodgroup + Ben Frost + Þórir The Lonesome Traveller is Out and About • Going Vegan in Svið-land • Ragnar Kjartansson Finds God Awakening the Couch Potatoes • Icelanders and their Elves • Sequences Art Festival + info. A Complete City Guide and Listings: Map, Dining, Music, Arts and Events Issue 16 // Oct 5 - Nov 1 2007 2557 CIN Grapevine jona 330 MBL.ai 10/3/07 12:07:01 PM 02 | Reykjavík Grapevine | Issue 16 2007 | Year 5 | October 05 – November 01 The Reykjavík Grapevine Articles Vesturgata 5, 101 Reykjavík www.grapevine.is Elves in Cultural Vocabulary 06 [email protected] Interview with professor Terry Gunnel www.myspace.com/reykjavikgrapevine Published by Fröken ehf. I am Going For a Cup of Coffee 08 Opinion by Viktor Banke Editorial: +354 540 3600 / [email protected] The Grapevine Guide to the Airwaves Personalities 08 Advertising: Opinion by Sveinn Birkir Björnsson +354 540 3605 / [email protected] Publisher: Vegan Iceland? 10 +354 540 3601 / [email protected] The Difficulties of Being a Vegan in Iceland The Reykjavík Grapevine Staff Can We Do This Indefinately? 12 Publisher: Interview with designer Olof Kolte Hilmar Steinn Grétarsson [email protected] Airwaves Special 14 Editor: Interviews with Ben Frost, Bloodgroup, Þórir and Mr. Silla & Mongoose Sveinn Birkir Björnsson / [email protected] Assistant Editor: Singing Painting at Nylo 20 Steinunn Jakobsdóttir / [email protected] Interview with artist Ragnar Kjartansson Editorial Intern: Valgerður Þóroddsdóttir -

De La Música, Lo Bello Y Las Sombras. La Compleja Relación De Joy Division Con La Estética De Lo Oscuro

149 De la música, lo bello y las sombras. La compleja relación de Joy Division con la estética de lo oscuro Dr. Pompeyo Pérez Díaz Universidad de La Laguna Resumen El papel de Joy Division como uno de los grupos impulsores del rock gótico es difícilmente discutible. Sin embargo, los rasgos sono- ros y estéticos de su propuesta presentan notables diferencias con otras bandas referenciales de dicha corriente, como Siouxsie & The Banshees, The Cure o Bauhaus. Los seguidores de estas, sin embar- go, siempre se mostraron receptivos hacia sus letras, su música y sus austeros conciertos. Hay algo extremo y/o radical en su plantea- miento que es percibido como oscuro por naturaleza. Este vínculo entre Joy Division y una estética gótica más canónica se vio refor- zado por un suceso inesperado, la muerte de Ian Curtis. Su suicidio consolidó el proceso de conversión de Joy Division en una banda de culto al tiempo que otorgó una “credibilidad” excepcional a la carga poética de las letras y al sonido descarnado de su música. I. Shadow at the side of the road Always reminds me of you� Ian Curtis. Komakino (1980) Joy Division 150 151 mentos normalmente asociados a la música de baile), el intercambio de los roles tradicionales del rock entre la guitarra y el bajo, la originalidad en el uso de sintetizadores y cajas de ritmos como un elemento más del sonido del grupo y, claro, la atmósfera global, una producción tan cuidadosa como premeditadamente minimalista, capaz de generar in- sospechados estados anímicos en el oyente1� La emocionalidad contenida a la que me he referido quizá sea una de las señas sonoras del grupo� Hay algo extremo y desesperado en ello, como en el grito que no se oye en el cuadro de Munch, ahí se encuentra parte de la identidad de Joy Division. -

Peter Saville: the Uk's Most Famous Graphic Designer

IDENTICA VISITS: PETER SAVILLE IN CONVERSATION WITH PAUL MORLEY Identica’s CEO Richard Morris, this week visited the V&A for the opening evening of the IDENTICA Global Design Forum. Brand Strategy & Design www.identica.co.uk The headline event saw Britain’s most celebrated graphic designer, Peter Saville in For more information please conversation with design critic and contact Leah Williams on commentator, Paul Morley. +44 (0)20 34519717 or [email protected] The Global Design Forum is an annual event triumphing thought leadership from the world of design. This is an insight into that conversation documented by Richard. A series of key thoughts and stories thrown out from the V&A discussion. A GRAPHIC DESIGNER PETER SAVILLE: the uk’S MOST FAMOUS GRAPHIC DESIGNER Peter Saville is an artist and designer whose contribution to culture, especially in Britain has been unique. Throughout his early art-directing days, Saville accessed a mass audience through the sub-cultures of pop music. This is best exemplified in a series of record sleeve artworks for Joy Division and New Order throughout the eighties. As co-founder of Factory Records, he cites the company’s idealism, rather than any commercial objective allowed him to communicate ideas, aesthetics and ultimately values to an audience he cherished. Saville’s achievements were celebrated in 2003 at London’s Design Museum, at a show entitled, The Peter Saville Show. The show later travelled to Manchester and Tokyo. THE V&A The V&A Museum was just one of the venues for this years Global Design Forum but was the setting for Saville’s and Morley’s forum discussion.