The Ideal and the Actual in Procedural Due Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository August 2016 Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E. Morley The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts © Briana E. Morley 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Morley, Briana E., "Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3991. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3991 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Abstract There is a dark mythology surrounding the post-punk band Joy Division that tends to foreground the personal history of lead singer Ian Curtis. However, when evaluating the construction of Joy Division’s public image, the contributions of several other important figures must be addressed. This thesis shifts focus onto the peripheral figures who played key roles in the construction and perpetuation of Joy Division’s image. The roles of graphic designer Peter Saville, of television presenter and Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, and of photographers Kevin Cummins and Anton Corbijn will stand as examples in this discussion of cultural intermediaries and collaborators in popular music. -

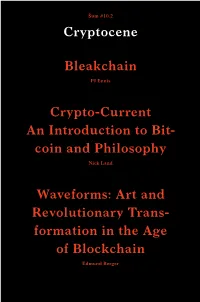

Coin and Philosophy Bleakchain Waveforms

Šum #10.2 Cryptocene Bleakchain PJ Ennis Crypto-Current An Introduction to Bit- coin and Philosophy Nick Land Waveforms: Art and Revolutionary Trans- formation in the Age of Blockchain Edmund Berger Šum #10.2 Cryptocene 1343 Partnerji in koproducenti Publikacija je nastala v okviru projekta State Machines, ki ga izvajajo Aksioma (SI), Drugo more (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) in NeMe (CY). Izvedba tega projekta je financirana Društvo s strani Evropske komisije. Vsebina komunikacije je izključno odgovornost avtorja in v nobenem primeru ne predstavlja stališč Evropske komisije. Galerija BOKS drustvoboks.wordpress.com Društvo Igor Zabel www.igorzabel.org Realized in the framework of State Machines, a joint project by Aksioma (SI), Drugo more (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) and NeMe (CY). Galerija Galerija This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission Kapelica Škuc cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. www.kapelica.org galerija.skuc-drustvo.si PartnerjiŠum in koproducenti#10.2 PartnerjiŠum in koproducenti#10.2 MGLC UGM Mednarodni grafični likovni center Umetnostna galerija Maribor www.ugm.si www.mglc-lj.si Mestna Zavod Celeia Celje galerija Ljubljana Center sodobnih umetnosti www.celeia.info www.mgml.si/ mestna-galerija-ljubljana MG+MSUM Aksioma OSMO/ZA Moderna galerija www.aksioma.org www.osmoza.si www.mg-lj.si 1346 1347 Šum #10.2 Šum #10.2 Bleakchain PJ Ennis 1349 Bleakchain PJ Ennis 1355 Crypto-Current An Introduction to Bitcoin and Philosophy nick Land 1373 Waveforms: Art and Revolutionary Transformation in the Age of Blockchain Edmund BErgEr The following is source material drawn from Tropical by PJ Ennis, a novel about the collapse of a post-cryptocurrency society in the thirty-first century. -

De La Música, Lo Bello Y Las Sombras. La Compleja Relación De Joy Division Con La Estética De Lo Oscuro

149 De la música, lo bello y las sombras. La compleja relación de Joy Division con la estética de lo oscuro Dr. Pompeyo Pérez Díaz Universidad de La Laguna Resumen El papel de Joy Division como uno de los grupos impulsores del rock gótico es difícilmente discutible. Sin embargo, los rasgos sono- ros y estéticos de su propuesta presentan notables diferencias con otras bandas referenciales de dicha corriente, como Siouxsie & The Banshees, The Cure o Bauhaus. Los seguidores de estas, sin embar- go, siempre se mostraron receptivos hacia sus letras, su música y sus austeros conciertos. Hay algo extremo y/o radical en su plantea- miento que es percibido como oscuro por naturaleza. Este vínculo entre Joy Division y una estética gótica más canónica se vio refor- zado por un suceso inesperado, la muerte de Ian Curtis. Su suicidio consolidó el proceso de conversión de Joy Division en una banda de culto al tiempo que otorgó una “credibilidad” excepcional a la carga poética de las letras y al sonido descarnado de su música. I. Shadow at the side of the road Always reminds me of you� Ian Curtis. Komakino (1980) Joy Division 150 151 mentos normalmente asociados a la música de baile), el intercambio de los roles tradicionales del rock entre la guitarra y el bajo, la originalidad en el uso de sintetizadores y cajas de ritmos como un elemento más del sonido del grupo y, claro, la atmósfera global, una producción tan cuidadosa como premeditadamente minimalista, capaz de generar in- sospechados estados anímicos en el oyente1� La emocionalidad contenida a la que me he referido quizá sea una de las señas sonoras del grupo� Hay algo extremo y desesperado en ello, como en el grito que no se oye en el cuadro de Munch, ahí se encuentra parte de la identidad de Joy Division. -

Understanding Joy Division Martin J. Power, Aileen Dillane and Eoin

This is the way, Step inside: Understanding Joy Division Martin J. Power, Aileen Dillane and Eoin Devereux Joy Division On the 30th of July 1980, three musicians - Peter Hook, Steven Morris and Bernard Sumner - took to the small stage of The Beach Club at Oozits Bar in Shudehill, Manchester. With what might be best described as ‘gallows humour’, Sumner introduced the band as being the last surviving members of Crawling Chaos (New Order Net 2018).1 Their short set consisted of five songs. It must have been a particularly difficult gig for the musicians to play, as just eleven week’s earlier their close friend and Joy Division band-mate Ian Curtis had committed suicide on the eve of their first tour of the United States. Curtis’s unexpected death marked the premature end of one of the most important and most influential post-punk bands. Joy Division was no more. Strictly speaking, Joy Division existed for only two and a half years. Formed in Salford, over twenty-nine months the band wrote and recorded forty-three songs and played one hundred and twenty gigs (see Joy Division Official 2018). The 1976 punk explosion served as an initial catalyst for Sumner and Hook to form a band - temporarily called Stiff Kittens. This was soon followed by the adoption of the name Warsaw, inspired by David Bowie’s ‘Warszawa’ and further changes in membership. The final line up of Curtis (vocals); Hook (bass); Sumner (guitar, keys) and Morris (drums) performed and recorded as Warsaw in the second half of 1977. However, the existence of a punk band called Warsaw Pakt convinced them to change their name to avoid any confusion and in January 1978 they played their first ever gig under the name Joy Division. -

Don Dombowsky IAN CURTIS and the GERMAN AUTUMN1

Don Dombowsky IAN CURTIS AND THE GERMAN AUTUMN1 he lyrics of Ian Curtis have typically been interpreted in two ways: either as a somber illustration of his psychological struggles (including his struggle with epilepsy) emphasizing his personal, ‘inner world’ T 2 and recognizing ‘his words as a literal cry for help’; or as a social and political refl ection of Manchester’s desolate, post-industrial spaces and of the economic and political transformations attending the emergence of the Thatcher era and its ‘authoritarian populism’,3 capturing the frustration and despair of the British working class and their ‘winter of discontent’. This concluding perspective is expressed in a most evocative way by Jon Savage who wrote in a Melody Maker review of Unknown Pleasures in 1979— explaining both Joy Division’s sonic idiom and the sensibility infusing the lyrics of Ian Curtis— that Joy Division’s spatial, circular themes’ [were a] ‘perfect refl ection of Manchester’s dark spaces and empty places: endless sodium lights... vacant industrial sites— the endless detritus of the 19th century... [communicating] the reactions of individuals caught in a trap they dimly perceive— anger, paranoia, alienation, feelings of thwarted power... [and] control everywhere. 4 And by Chris Ott as well, by the time of his writing expressing the by then standard view that as personal and emotional as Curtis’s lyrics were, the sense of despair and frustration that they conveyed had broad implications in the England of the late 1970s, where hopelessness was a very real sensation. The economic downturn resulted in labor strikes ranging from garbage workers to nurses to gravediggers.5 1 This essay appeared in the form of a didactic poem in: Epizootics! Online Literary Journal for the Contemporary Animal. -

A Study to Understand Manchester's Emergence As

A STUDY TO UNDERSTAND MANCHESTER’S EMERGENCE AS A CREATIVE CITY. Jordan Strong History BA Honours dissertation Aberystwyth University 9th May 2014 1 Acknowledgements Throughout this piece of work I have had some fantastic support, critiques and feedback, never more so then from Barbara Jones of student support at the university. Her support, motivation and editing of this piece of work has been second to none. The process of writing a dissertation is a hard task as it is without the persistence of dyslexia, but with Barbara’s help, the process has been as smooth as one could hope. It has been a long, hard process with some laughs along the way, I am truly grateful for her help. I would also like to thank Dr. Richard Coopey, his supervision has been excellent, his guidance with source material has been extremely beneficial to this study. Furthermore I would like to thank Suzannah Reeves of Oldham sixth form college for helping me contact Dave Haslem, Also Dave himself for taking time out to email me. Finally those who helped me at the Museum of Science and Industry during in the couple of days I spent at the Rob Gretton Archive. 2 Table of content 1. Introduction p.3 2. Chapter One – ‘The scene is very humdrum’ p.7 3. Chapter Two – ‘Evidently Chickentown’ p.14 4. Chapter Three – ‘The Hacienda must be built’ p.25 5. Chapter Four – ‘I don’t have to see my soul he is already in me’ p.39 6. Conclusion p.44 3 Introduction On the 16th of August, 1819, eighteen people were massacred during a peaceful protest in Manchester’s St. -

White Stripes White Stripes the Hives the Hives

FOE #419 DECEMBER 2007 www.frankfoe.com [email protected] www.myspace.com/foezine WORDS ON MY MIND WORDS ABOUT RECORDED MUSIC 2007 is turning out to be a fantastic year for music. White Stripes There are so many great records out there right “You Don’t Know What Love Is/A Martyr For My now, I know it is going to be ridiculously hard to Love (acoustic)” 7” Warner Bros 2007 come up with a year end Top Ten. By now you know the rock n roll that is the White The great year in music, is definitely helping my Stripes. The A Side is one of the Stripes best mood. Sometimes I forget how connected I am to songs. Great groove, great music, great lyrics, something as simple as music and to deny oneself great hook… great rock n roll. The B-side is the of that can be quite devastating. acoustic version of “A Martyr…” and is truly worth the price I paid at Hot Topic for this 7”. Exceptional, Welcome to FOE. especially with headphones on. No hype, just a great record by a great band. WORDS OTHERS SAID Music expresses that which cannot be said and on which it is impossible to be silent. Victor Hugo Take a music bath once or twice a week for a few seasons, and you will find that it is to the soul what the water-bath is to the body. Oliver Wendell Holmes The Hives “Tick Tick Boom/Hell No” 7” Polydor 2007 Without music, life would be an error. -

Toonzetters Tegendraadse Muziek Uit Een Nieuwe Werkplaats

Toonzetters Tegendraadse muziek uit een nieuwe werkplaats Listen to the silence, let it ring on Eyes, dark grey lenses frightened of the sun We would have a fine time living in the night, Left to blind destruction, Waiting for our sight Robert de Vaan 301111 DT4 KAL2 Toonzetters INHOUD (BLZ/HST/TITEL) 2 0. VOOR 3 1. JONGERENCULTUUR IN DE 20e EEUW:MASSA EN TEGENCULTUUR 4 2. PUNK 6 3. NEW WAVE 6 4. TONY WILSON 7 5 CLUBS 8 6. FACTORY RECORDS 9 7 JOY DIVISION 11 8. NEW ORDER 12 9. ACHTER 13 B1 BIJLAGE 1: ONAFHANKELIJKE LABELS IN DE JAREN 80 14 B2 BIJLAGE 2: FACTORY CATALOGUS 21 B3 BIJLAGE 3: BRONNNEN 0. VOOR Er bestaan in mijn optiek maar twee stromingen binnen de muziek, te weten goede en slechte. De goede is doorgaans authentiek en de gevoelens die Ian Curtis, frontman van Joy Division, bezong leken mij als tiener in de jaren 80 oprecht, hij had er niet voor niets een einde aan gemaakt. De muziek hoorde bij de stroming New Wave, waar ik actief onderdeel van werd . Generatie Nix, de naam die mijn generatie meekreeg, zou toch geen werk vinden en de atoomoorlog zou spoedig beginnen. I wear black on the outside because black is how I feel on the inside zei Morrisey en daar kan ik me tot op de dag van vandaag in vinden... In dit referaat ga ik op zoek naar mijn muzikale en sociale roots en naar de achtergronden van het verhaal van een bijzondere en alternatieve onderneming. New Wave, de stroming voor de subcultuur der alternatieven waarvan Ian Curtis pionier was, vond zijn oorsprong halverwege de jaren 70 in de tegendraadse Punk. -

Michael Bevilacqua

in this about media guide back video gallery artists 101 ISSUE ARTVOICES ADVERTISE COVERS GALLERY GUIDE STORE Reviews MICHAEL BEVILACQUA MICHAEL BEVILACQUA The Magazine October 2012 Written by Chris Bors 0 Comments Art In Architecture Like 33 Tweet 3 1 Art Matters GERING & LOPEZ GALLERY · New York, NY Berlin Art Scene ften finding himself listening to one Joy Division song on repeat for weeks at a time, Michael O Bevilacqua took one year to finish the massive 30-foot-long canvas An Ideal For Living, 2012, Cornerstone letting the music be more than just background entertainment. Immersing himself in the legendary Manchester-based band’s whole output, including rare recordings, Bevilacqua may have found the Cover Story perfect soundtrack for his work and his life. Starting with a stripped-down, punk attitude, as heard in their An Ideal For Living EP, the post-punk pioneers quickly morphed into a moody, shifting, cerebral Editor's Letter band that was hard to pin down. Composed of three panels, Bevilacqua’s tribute to Joy Division, including an image lifted from the first EP of a Hitler Youth drummer boy, uses a wide variety of Features painterly techniques that parallel the band’s diverse sound. Using acrylic, spray paint, and graffiti paint markers, hard-edged sections overlap stains, drips, patterns, textures, and words that function as In The Studio signifiers for the band’s recordings. Inside Out Newcomer 25 Artists to Watch & Collect Poetry in Motion Pulse An Ideal For Living, 2012, acrylic, spray paint & molotow pen on linen, 96” x 360” COURTESY GERING & LÓPEZ GALLERY Reviews If painting An Ideal For Living was a form of catharsis, it may have also further loosened Bevilacqua’s approach to tackling a canvas both formally and conceptually. -

Article Factory Records and the Situationist Influence on Urban Space

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK Article Factory records and the situationist influence on urban space Ingham, James Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/15785/ Ingham, James (2016) Factory records and the situationist influence on urban space. Punk & Post Punk, 5 (2). pp. 163-179. ISSN 2044-1983 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/punk.5.2.163_1 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/policies/ CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk Factory records and the situationist influence on urban space James Ingham, University of Central Lancashire Abstract There has been a substantial amount of literature on Factory Records and Manchester, with some exploring the urban influence on music and its associated local identities. Writing on post-punk has also considered regional and local influences. This article proposes a new approach with a detailed consideration of the Situationist influence and wider European radical theory on Factory Records. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #6: Factory Records

Boo-Hooray Catalog #6: The Factory Catalog Terms: Usual. Not onerous. Boo-Hooray is proud to present our sixth antiquarian catalog, The Factory Catalog. This catalog gathers pieces from the material history of one of the most forward-thinking record labels of the 20th Century. Renowned for inventive and genre-pushing music, innovative design, and a tongue-in-cheek take on themselves and the world, Factory Records helped shape the post-punk era as well as modern design and typography. Reflecting their deep involvement in the creation of not just records but an alternative music subculture, social scene, and aesthetic language, Factory Records gave catalog numbers to virtually anything associated with the label. Accessioning items as seemingly unimportant as stationery and Christmas gifts, along with more serious projects like their club and promotional campaigns, fostered the cheeky and self- aware personality that distinguished Factory from corporate labels and overly self-serious independents. This catalog includes the unreleased and exceptionally rare FAC 1 poster, the hand-drawn original flipbook by Robert Breer and William Wegman for the Blue Monday '88 video, and tons of original poster, flyers, and broadsides made for Factory Records. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger; Dominic Masi Jr., Head Music Archivist; and Daylon Orr, Executive Director. -

Il Musicista Inglese in Concerto Al Quirinetta Di Roma Lo Scorso 7 Aprile

RECENSIONI ANNO VII 2017 lunedì 10 aprile Il musicista inglese in concerto al Quirinetta di Roma lo scorso 7 aprile di DANILA SCOTTON enerdì 7 aprile, sul palco uscì nel 1987 e includeva le ver- ziatori e giri di tastiere avvolgono del Quirinetta si è esibito sioni dodici pollici dei loro singoli, e catturano l’energia dei presenti V Peter Hook, icona del rock più parecchie b-sides con canzoni che, ballando, “condividono” la che ha iniziato il suo tour mondi a- come Temptation. Nel 1988 esce performance dell’artista e del suo le da Roma presentando le due la versione dedicata ai Joy divi- team. Due ore e mezza di musica storiche compilation intitolate Sub- “da sballo”, con un pubblico etero- sion che conteneva singoli memo- stance. Meglio conosciuto come rabili come Love will tear us apart, geneo di tutte le età, animano un bassista della band “Joy division” Tran smission, Komakino, Atmo- evento che ripercorre i trascorsi – in cui ha militato dal 1977 al sph ere, An ideal for living oltre ad musicali rock, pop e perfino dance 1980 e successivamente dei “New altre b-sides. Nella versione ar- con i Joy division, proseguendo order” tra il 1980 e il 2007 –, nel rangiata presentata a Roma, tutta nel post punk più malinconico e 2010 fonda i “Peter Hook and the la potenza e l’energia cruda del tragico dei New order e nella New light”, gruppo con cui suona i mi- punk sono esaltate dalla voce wave. Al di là delle collocazioni di gliori successi del repertorio dei genere, quella di Peter Hook è graffiante e imponente di Hook.