1 Doris Miller: Messboy, Steward, Cook, Hero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Wilkey Journal on Board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey

Thomas Wilkey journal on board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 22, 2014 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Library Company of Philadelphia 2012 March 10 Thomas Wilkey journal on board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 - Page 2 - Thomas Wilkey journal on board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey Summary Information Repository Library Company of Philadelphia Creator Wilkey, Thomas Title Thomas Wilkey journal -

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport The Last Battle of the Revolution Less than a quarter of a century after the close of the American Revolution, Great Britain and the United States were again in conflict. Britain and her allies were engaged in a long war with Napoleonic France. The shipping-related industries of the neutral United States benefited hugely, conducting trade with both sides. Hundreds of ships, built in yards on America’s Atlantic coast and manned by American sailors, carried goods, including foodstuffs and raw materials, to Europe and the West Indies. Merchants and farmers alike reaped the profits. In Cambridge, men made plans to profit from this brisk trade. “[T]he soaring hopes of expansionist-minded promoters and speculators in Cambridge were based solidly on the assumption that the economic future of Cambridge rested on its potential as a shipping center.” The very name, Cambridgeport, reflected “the expectation that several miles of waterfront could be developed into a port with an intricate system of canals.” In January 1805, Congress designated Cambridge as a “port of delivery” and “canal dredging began [and] prices of dock lots soared." [1] Judge Francis Dana, a lawyer, diplomat, and Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, was one of the primary investors in the development of Cambridgeport. He and his large family lived in a handsome mansion on what is now Dana Hill. Dana lost heavily when Jefferson declared an embargo in 1807. Britain and France objected to America’s commercial relationship with their respective enemies and took steps to curtail trade with the United States. -

K a L E N D E R- B L Ä T T E R

- Simon Beckert - K A L E N D E R- B L Ä T T E R „Nichts ist so sehr für die „gute alte Zeit“ verantwortlich wie das schlechte Gedächtnis.“ (Anatole France ) Stand: Januar 2016 H I N W E I S E Eckig [umklammerte] Jahresdaten bedeuten, dass der genaue Tag des Ereignisses unbekannt ist. SEITE 2 J A N U A R 1. JANUAR [um 2100 v. Chr.]: Die erste überlieferte große Flottenexpedition der Geschichte findet im Per- sischen Golf unter Führung von König Manishtusu von Akkad gegen ein nicht bekanntes Volk statt. 1908: Der britische Polarforscher Ernest Shackleton verlässt mit dem Schoner Nimrod den Ha- fen Lyttelton (Neuseeland), um mit einer Expedition den magnetischen Südpol zu erkunden (Nimrod-Expedition). 1915: Die HMS Formidable wird in einem Nachtangriff durch das deutsche U-Boot SM U 24 im Ärmelkanal versenkt. Sie ist das erste britische Linienschiff, welches im Ersten Weltkrieg durch Feindeinwirkung verloren geht. 1917: Das deutsche U-Boot SM UB 47 versenkt den britischen Truppentransporter HMT In- vernia etwa 58 Seemeilen südöstlich von Kap Matapan. 1943: Der amerikanische Frachter Arthur Middleton wird vor dem Hafen von Casablanca von dem deutschen U-Boot U 73 durch zwei Torpedos getroffen. Das zu einem Konvoi gehörende Schiff ist mit Munition und Sprengstoff beladen und versinkt innerhalb einer Minute nach einer Explosion der Ladung. 1995: Die automatische Wellenmessanlage der norwegischen Ölbohrplattform Draupner-E meldet in einem Sturm eine Welle mit einer Höhe von 26 Metern. Damit wurde die Existenz von Monsterwellen erstmals eindeutig wissenschaftlich bewiesen. —————————————————————————————————— 2. JANUAR [um 1990 v. Chr.]: Der ägyptische Pharao Amenemhet I. -

Legacy of the Pacific War: 75 Years Later August 2020

LEGACY OF THE PACIFIC WAR: 75 YEARS LATER August 2020 World War II in the Pacific and the Impact on the U.S. Navy By Rear Admiral Samuel J. Cox, U.S. Navy (Retired) uring World War II, the U.S. Navy fought the Pacific. World War II also saw significant social in every ocean of the world, but it was change within the U.S. Navy that carried forward the war in the Pacific against the Empire into the Navy of today. of Japan that would have the greatest impact on As it was at the end of World War II, the premier Dshaping the future of the U.S. Navy. The impact was type of ship in the U.S. Navy today is the aircraft so profound, that in many ways the U.S. Navy of carrier, protected by cruiser and destroyer escorts, today has more in common with the Navy in 1945 with the primary weapon system being the aircraft than the Navy at the end of World War II had with embarked on the carrier. (Command of the sea first the Navy in December 1941. With the exception and foremost requires command of the air over the of strategic ballistic missile submarines, virtually Asia sea, otherwise ships are very vulnerable to aircraft, every type of ship and command organization today Program as they were during World War II.) The carriers and is descended from those that were invented or escorts of today are bigger, more technologically matured in the crucible of World War II combat in sophisticated, and more capable than those of World Asia Program War II, although there are fewer of them. -

An Incomplete History of the USS FISKE (DD/DDR 842)

An Incomplete History of the USS FISKE (DD/DDR 842) For The Fiske Association Prepared by R. C. Mabe – Association Historian October 1999 Edited & revised by G. E. Beyer – Association Historian September 2007 Introduction The USS FISKE was a Gearing Class destroyer, the last of the World War II design destroyers. She served in the US Navy from 1945 until 1980 and was subsequently transferred to the Turkish Navy where she served as the TCG Piyale Pasa (D350). The former FISKE was heavily damaged in 1996 when she ran aground and was scrapped in early 1999. Altogether the FISKE served two navies for over 54 years. I am titling this report as an „Incomplete History of the USS Fiske DD/DDR 842‟ for the simple reason that it not complete. I am continuing to try and fill the gaps and inconsistencies to the best of my ability. Any help in this effort will be appreciated. The Soul of a Ship Now, some say that men make a ship and her fame As she goes on her way down the sea: That the crew which first man her will give her a name – Good, bad, or whatever may be. Those coming after fall in line And carry the tradition along – If the spirit was good, it will always be fine – If bad, it will always be wrong/ The soul of a ship is a marvelous thing. Not made of its wood or its steel, But fashioned of mem‟ries and songs that men sing, And fed by the passions men feel. -

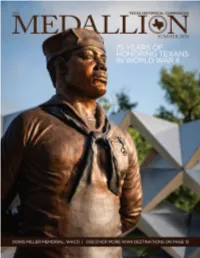

Texans Have Always Contributed a Surplus of Soldiers and Resources to the Nation’S Military

ISSN 0890-7595 Vol. 58, No. III thc.texas.gov [email protected] TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION John L. Nau, III Chair John W. Crain Vice Chair Gilbert E. “Pete” Peterson Secretary Earl Broussard, Jr. David A. Gravelle James “Jim” Bruseth Chief Justice Wallace B. Jefferson (ret.) Monica P. Burdette Laurie E. Limbacher Garrett Kieran Donnelly Catherine McKnight Renee Rupa Dutia Tom Perini Lilia Marisa Garcia Daisy Sloan White Mark Wolfe Executive Director Medallion STAFF Chris Florance Division Director Andy Rhodes Managing Editor Judy Jensen Sr. Graphic Design Coordinator TEXAS HISTORICAL thc.texas.gov Real places telling the real stories of Texas COMMISSION texastimetravel.com The Texas Heritage Trails LEADERSHIP LETTER Program’s travel resource texashistoricsites.com The THC’s 32 state historic properties thcfriends.org Friends of the Texas Historical Commission As veterans of the armed services, we’re honored to Learn about him at the modernized Nimitz Our Mission introduce The Medallion magazine issue commemo- Museum, part of the THC’s National Museum To protect and preserve the state’s historic and prehistoric of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, his hometown. resources for the use, education, enjoyment, and economic rating the roles played by Texas and Texans in World benefit of present and future generations. War II on the 75th anniversary of the end of the The Eisenhower Birthplace State Historic Site in global conflict. The Medallion is published quarterly by the Texas Historical Denison offers visitors background on General Commission. Address correspondence to: Managing Editor, The Medallion, P.O. Box 12276, Austin, TX 78711-2276. Portions While the war was horrific in every sense, the Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in of the newsletter that are not copyrighted or reprinted from other following articles help us understand the sacrifices Europe and future President of the United States. -

Marshall U. Beebe, Captain, USN No Picture Available

Officer of Fighter Squadron 17, a squadron of F6F Hellcats of Air Group 17, based on the USS Hornet, in the Pacific. He remained in that command until June 1945, during which period he participated in the first Navy raids on Tokyo in February 1945 and was personally credited with 10 1/2 Japanese planes. He was awarded the Navy Cross for "extraordinary heroism as a Pilot and Flight Loader in Fighting Squadron 17 ...in the vicinity of Southern Kyushu, No picture available Japan, on March 18, 1945...where he shot down five planes of twenty-five destroyed by his flight of 16 aircraft... also accounted for two aircraft destroyed on the ground, probably destroyed another in the air and damaged two others...” From June 1945 until June 1946 he again served in the Navy Department, this time in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations, where he was assigned to Military Requirements, Armament Desk, and for a year thereafter he was a student at the General Line School, Newport, Rhode Island. In July 1947 he reported to the USS Badoeng Marshall U. Beebe, Captain, USN Strait, in which he served as Air Officer until March 1948. (Naval Aviator Number 5534) He then became Aide and Flag Lieutenant on the Staff of Admiral Arthur W. Radford, USN, then Vice Chief of Naval Marshall Ulrich Beebe was born in Anaheim, California, Operations, and later Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet on August 6, 1913, son of Marshall E. and Anna M, (Ulrich) Beebe. He attended Occidental College, majoring in math- In July 1950 he reported to Commander Air Force, ematics and physics, and graduated with a degree of Bachelor Pacific as Prospective Commander of Carrier Air Group 5, of Arts in 1935. -

World War Ii Wall of Honor

WORLD WAR II WALL OF HONOR WINCHESTER WALL OF HONOR – Participating in the national effort of the Spirit of ’45 to photo-document the veterans of WWII, Winchester’s World War II 75th Anniversary Committee has compiled a Winchester Wall of Honor. Shown below is the collection to date. Residents and veterans’ families are invited and encouraged to contribute photos of veterans who enlisted from Winchester for both the local and national walls. On parade 1949 On parade 1950 An early version of the project displayed in Winchester Town Hall. The “wall” will be kept as Although the Wall of Honor does not include all who a digital supplement to the enlisted from Winchester, new photos may be contributed WWII veterans database. to photo-document further service men and women. Information about the people pictured is also welcome. The photos below have come from yearbooks, archival photo collections, newspapers, the Internet, and families. Although photographs of service men and women in uniform were preferred, many school photographs and a few of men in the uniforms of the Fire Department have been used with an effort to show the men and women as close to the age of enlistment as possible. The project, though designed for the 75th Anniversary of WWII, is still open to the contribution of further photographs, all to be kept in the Winchester Archival Center, which also has a database of all known veterans who enlisted from Winchester. TO CONTRIBUTE PHOTOGRAPHS: please e-mail scans to [email protected] or bring in photos during Archival Center open hours for copying. -

Appendix As Too Inclusive

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Appendix I A Chronological List of Cases Involving the Landing of United States Forces to Protect the Lives and Property of Nationals Abroad Prior to World War II* This Appendix contains a chronological list of pre-World War II cases in which the United States landed troops in foreign countries to pro- tect the lives and property of its nationals.1 Inclusion of a case does not nec- essarily imply that the exercise of forcible self-help was motivated solely, or even primarily, out of concern for US nationals.2 In many instances there is room for disagreement as to what motive predominated, but in all cases in- cluded herein the US forces involved afforded some measure of protection to US nationals or their property. The cases are listed according to the date of the first use of US forces. A case is included only where there was an actual physical landing to protect nationals who were the subject of, or were threatened by, immediate or po- tential danger. Thus, for example, cases involving the landing of troops to punish past transgressions, or for the ostensible purpose of protecting na- tionals at some remote time in the future, have been omitted. While an ef- fort to isolate individual fact situations has been made, there are a good number of situations involving multiple landings closely related in time or context which, for the sake of convenience, have been treated herein as sin- gle episodes. The list of cases is based primarily upon the sources cited following this paragraph. -

The United States Navy Looks at Its African American Crewmen, 1755-1955

“MANY OF THEM ARE AMONG MY BEST MEN”: THE UNITED STATES NAVY LOOKS AT ITS AFRICAN AMERICAN CREWMEN, 1755-1955 by MICHAEL SHAWN DAVIS B.A., Brooklyn College, City University of New York, 1991 M.A., Kansas State University, 1995 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2011 Abstract Historians of the integration of the American military and African American military participation have argued that the post-World War II period was the critical period for the integration of the U.S. Navy. This dissertation argues that World War II was “the” critical period for the integration of the Navy because, in addition to forcing the Navy to change its racial policy, the war altered the Navy’s attitudes towards its African American personnel. African Americans have a long history in the U.S. Navy. In the period between the French and Indian War and the Civil War, African Americans served in the Navy because whites would not. This is especially true of the peacetime service, where conditions, pay, and discipline dissuaded most whites from enlisting. During the Civil War, a substantial number of escaped slaves and other African Americans served. Reliance on racially integrated crews survived beyond the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, only to succumb to the principle of “separate but equal,” validated by the Supreme Court in the Plessy case (1896). As racial segregation took hold and the era of “Jim Crow” began, the Navy separated the races, a task completed by the time America entered World War I. -

Norfolk's Nauticus: USS Wisconsin BB‐64

Norfolk’s Nauticus: USS Wisconsin BB‐64 The history of the U.S. Navy’s use of battleships is quite interesting. Some say the first battleship was the USS Monitor, used against the CSS Virginia (Monitor) in Hampton Roads in 1862. Others say it was the USS Michigan, commissioned in 1844. It was the first iron‐ hulled warship for the defense of Lake Erie. In any case, battleships, or as some have nicknamed them “Rolling Thunder,” have made the United States the ruler of the high seas for over one century. A history of those famous ships can be found in the source using the term bbhistory. By the way, BB‐64 stands for the category battleship and the number assigned. This photo program deals with the USS Wisconsin, which is moored in Norfolk and part of the Hampton Road Naval Museum and Nauticus. Though the ship has been decommissioned, it can be recalled into duty, if necessary. On July 6, 1939, the US Congress authorized the construction of the USS Wisconsin. It was built at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Its keel was laid in 1941, launched in 1943 and commissioned on April 15, 1944. The USS Wisconsin displaces 52,000 tons at full load, length 880 fee, beam 108 feet and draft at 36 feet. The artillery includes 16‐inch guns that fire shells weighing one‐ton apiece. Other weapons include antiaircraft guns and later added on missile launchers. The ship can reach a speed of 30 nautical miles (knots) per hour or 34 miles mph. The USS Wisconsin’s first battle star came at Leyte Operation, Luzon attacks in the Pacific in December 1944. -

Black Sailors, White Dominion in the New Navy, 1893-1942 A

“WE HAVE…KEPT THE NEGROES’ GOODWILL AND SENT THEM AWAY”: BLACK SAILORS, WHITE DOMINION IN THE NEW NAVY, 1893-1942 A Thesis by CHARLES HUGHES WILLIAMS, III Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2008 Major Subject: History “WE HAVE . KEPT THE NEGROES’ GOODWILL AND SENT THEM AWAY”: BLACK SAILORS, WHITE DOMINION IN THE NEW NAVY, 1893-1942 A Thesis by CHARLES HUGHES WILLIAMS, III Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, James C. Bradford Committee Members, Julia Kirk Blackwelder Albert Broussard David Woodcock Head of Department, Walter Buenger August 2008 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “We have . kept the negroes’ goodwill and sent them away”: Black Sailors, White Dominion in the New Navy, 1893-1942. (August 2008) Charles Hughes Williams, III, B.A., University of Virginia Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. James C. Bradford Between 1893 and 1920 the rising tide of racial antagonism and discrimination that swept America fundamentally altered racial relations in the United States Navy. African Americans, an integral part of the enlisted force since the Revolutionary War, found their labor devalued and opportunities for participation and promotion curtailed as civilian leaders and white naval personnel made repeated attempts to exclude blacks from the service. Between 1920 and 1942 the few black sailors who remained in the navy found few opportunities. The development of Jim Crow in the U.S.