Reducing Youth Exposure to Alcohol Ads: Targeting Public Transit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wine Beverage Alcohol Manual 08-09-2018

Department of the Treasury Alcohol & Tobacco Tax & Trade Bureau THE BEVERAGE ALCOHOL MANUAL (BAM) A Practical Guide Basic Mandatory Labeling Information for WINE TTB-G-2018-7 (8/2018) TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE OF THE BEVERAGE ALCOHOL MANUAL FOR WINE, VOLUME 1 INTRODUCTION, WINE BAM GOVERNING LAWS AND REGULATIONS CHAPTER 1, MANDATORY LABEL INFORMATION Brand Name ................................................................................................................................. 1-1 Class and Type Designation ........................................................................................................ 1-3 Alcohol Content ........................................................................................................................... 1-3 Percentage of Foreign Wine ....................................................................................................... 1-6 Name and Address ..................................................................................................................... 1-7 Net Contents ................................................................................................................................ 1-9 FD&C Yellow #5 Disclosure ........................................................................................................ 1-10 Cochineal Extract or Carmine ...................................................................................................... 1-11 Sulfite Declaration ...................................................................................................................... -

Drink Menu Specialty Drinks

Drink Menu Specialty Drinks Mai Thai………………………………………………………………………………………...…………. 7.5 Bacardi, pineapple & orange juice, grenadine and a dark rum float. Moscow Mule………………………………………………………………………….……...……7 Sobieski Vodka, fresh squeezed lime and Gosling’s ginger beer. (Make it a Dark & Stormy! Substitute the vodka for Dark Rum!) The Kinky Cosmo…………………………………………………………………...…………. 8 Ketel One Vodka, Kinky Liqueur, Triple Sec, cranberry juice and fresh squeezed orange. Shaken and strained. Shucks Bloody Mary………………………………………………………...…………. 8 Garnished with fresh shrimp, pepperoncini, pickle, lime and a green olive. (Lookin’ for a little extra spice? For a $1 more make it a Major Mary!) Pat O’ Brien’s Hurricane…………………………………………...…………. 7 A healthy pour of Dark rum mixed with Pat O’ Brien’s own hurricane mix! Louisiana Sunrise…………………………………………………….…...…………. 6.50 Southern Comfort, house punch, orange juice and sour.. The Oyster Shooter……………………………………………..……………...……….…. 6 Chilled Absolut Peppar Vodka, house made cocktail sauce and a fresh shucked oyster. The Beer On Tap Anchor Steam • Bud Light • Zipline IPA (Lincoln, NE) Goose Island 312 • Stella Artois Domestics Bud Light (20 oz. Aluminum) • Budweiser (20 oz. Aluminum) Busch Light (can) • Coors Light • Coors Light N/A • Michelob Ultra Miller Lite • PBR Tallboy 16oz can Micro Brews 90 Shilling Ale • Ace Pineapple Cider • Ace Perry Hard Cider • Blue Moon Boulevard Wheat • Brickway (Rotating) (Omaha, NE) • Deschutes Black Butte Porter • Deschutes Fresh Squeezed IPA • Founders All Day IPA • Glacial Till Original -

Fortified Wine Production

BEGINNER FORTIFIED WINE PRODUCTION Content contributed by Kimberly Bricker, Imperial Beverage Material contained in this document applies to multiple course levels. Reference your syllabus to determine specific areas of study. Wine was originally fortified, or strengthened, to better sustain itself during the journey to those importing it. The addition of brandy or neutral grape spirit would kill off the yeasts, which are constantly in the process of converting sugars to alcohol. Once the alcohol by volume reaches 16-18%, yeasts die. The remaining sugars are never converted into alcohol, and the natural sugars of the wine persist. Wines can be fortified at various stages in their fermentation, sweetened or colored with a variety of techniques. Different grape varietals can be used. Grapes can be dried. Wines can be boiled and reduced, cooked, aged in a solera, or aged in a boat that travels halfway across the world and back. They can be enjoyed immediately or aged for over 200 years. Port, Sherry, Madeira, Marsala, Malaga, Montilla-Moriles, and Vin Doux Naturels (VDN’s) are all Fortified Wines. Most people think of stuffy British old men drinking out of little glasses in a mahogany Sherry library with their pinkies out when they “Oh I must’ve been a dreamer think of Sherry- if they think of Sherry. And I must’ve been someone else While that image may have relegated Sherry, as an old-fashioned wine, to the And we should’ve been over back of the cool class, that is only part of Oh Sherry, our love the picture. Both Christopher Columbus Holds on, holds on…” and Ferdinand Magellan filled their ships ‘Oh Sherry’ by Steve Perry with Sherry when they set sail to discover the New World. -

WINE INDUSTRY BUSINESS JOURNAL: Who’S Who in Wine Law

pressdemocrat.com printer version http://www.busjrnl.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20090126/BUSINE... northbaybusinessjournal.com This is a printer friendly versio n o f an article fro m www.northbaybusinessjournal.com To print this article open the file menu and choose Print. Back Article published - Jan 26, 2009 WINE INDUSTRY BUSINESS JOURNAL: Who’s Who in Wine Law By D. Ashley Furness, Business Journal Staff Reporter The more than two dozen attorneys chosen for the Business Journal’s first Who’s Who in Wine Law represent a range of specialization and a deep appreciation of wine making, often extending to their own vineyards and vintages. Researchers surveyed attorneys from the largest 20 firms on the Business Journal’s 2008 “Legal Service Providers to the Wine Industry List,” and accepted recommendations from lo cal wineries and vineyards. Others were selected from Wine Institute suggestions, and several were also found through the Napa, Marin and Sonoma County bar associations. (Listed alphabetically by name) Richard Abbey Abbey, Weitzenberg, Warren & Emery, 100 Stony Point Road, Santa Rosa 95401, 707-542-5050, www.abbeylaw.com Abbey, Weitzenberg, Warren & Emery Partner Richard Abbey is considered one of the North Bay’s premier litigators, with close to 40 years in the business and a wide breadth of experience. He’s spent much o f his career representing financial institutio ns in co mmercial, co rpo rate, emplo yment and banking law, but in recent years he has also prioritized representation of those in the wine industry. He has served several years as a judge pro tem for the Sonoma County Superior Court, and he is a member of the Arbitration Panel for Sonoma County Consolidated Courts and fee arbitrator and past president of the Sonoma County Bar Association. -

Imperial Hops: How Beer Traveled the World, Especially to Asia Jeffrey M

Imperial Hops: How Beer Traveled the World, Especially to Asia Jeffrey M. Pilcher This is a very preliminary discussion of a book I hope to write on the globalization of beer. The first section outlines the literature and my research plan as sort of a first draft of a grant proposal intended to convince some funding agency to pay for me to travel the world drinking beer. The rest of the paper illustrates some of these ideas with three Asian case studies. I started with Asia in response to an invitation to participate in a recent SSRC Interasia Workshop in Istanbul and because the languages and meager secondary literature make it the hardest part of the project to research. There are mostly questions where the conclusions should be, and I welcome all suggestions. In June of 2013, Turkish crowds gathered in Istanbul’s Taksim Square to protest the growing authoritarianism of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Refusing to surrender their democratic freedoms, they opened bottles of Efes Pilsner and raised mock toasts to the tee-totaling Islamist politician: “Cheers, Tayyip!”1 The preference for European-style beer, rather than the indigenous, anise-flavored liquor arak, illustrates the complex historical movements that have shaped global consumer culture, and at times, political protests. Turkish entrepreneurs founded the Efes brewery in 1969, less than a decade after guest workers first began traveling to Germany and returning home with a taste for lager beer.2 This brief episode illustrates both the networks of migration, trade, and colonialism that carried European beer around the world in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the new drinking cultures that emerged as a result. -

Defining Cider Styles and Competitions

Exploring the Many Styles of Cider Eric West Founder – Cider Guide Director – Great Lakes International Cider & Perry Competition (GLINTCAP) [email protected] Great Lakes International Cider and Perry Competition (GLINTCAP) First held in 2005 at Great Lakes EXPO. 617 entries in 2015. 800-1000 expected in 2016. Most respected judging in North America. glintcap.org Great Lakes International Cider and Perry Competition (GLINTCAP) Standard Class Specialty Class New World Modern Cider New England Cider New World Heritage Cider Fruit Cider English Cider Applewine French Cider Hopped Cider Spanish Cider Spiced Cider New World Perry Wood-Aged Cider Traditional Perry Specialty Cider & Perry Unlimited Cider & Perry Mead Beer Great Lakes International Cider and Perry Competition (GLINTCAP) Intensified and Distilled Class Ice Cider Pommeau Eau de vie Brandy glintcap.org/styles New World Modern Cider New World broadly refers to the ciders typically made in the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Typically less than 7% ABV. Commonly grown apple varieties such as Winesap, Macintosh, Golden Delicious, Jonathan are used. Often packaged like craft beer: 12oz or 16oz bottles and cans, 22oz bottles, and on draft. New World Heritage Cider Inspired by Old World traditions but with a clean, New World fermentation. Typically 6-9% ABV. Heirloom and dual-purpose varieties like Northern Spy, Baldwin, Winesap, Rhode Island Greening, Newtown Pippin, Gravenstein. English and French apples are also used. Often packaged like wine: 375ml, 500ml, 750ml bottles. English Cider Typically drier and more austere than New World ciders. Often made with tannic varieties known as bittersweets and bittersharps. Natural fermentation often used. -

Chapter 1 – Alcoholic Beverages Definition –– a Potable

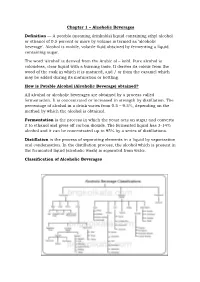

Chapter 1 – Alcoholic Beverages Definition –– A potable (meaning drinkable) liquid containing ethyl alcohol or ethanol of 0.5 percent or more by volume is termed as ‘alcoholic beverage’. Alcohol is mobile, volatile fluid obtained by fermenting a liquid containing sugar. The word ‘alcohol’ is derived from the Arabic al – kohl. Pure alcohol is colourless, clear liquid with a burning taste. It derives its colour from the wood of the cask in which it is matured, and / or from the caramel which may be added during its maturation or bottling. How is Potable Alcohol (Alcoholic Beverage) obtained? All alcohol or alcoholic beverages are obtained by a process called fermentation. It is concentrated or increased in strength by distillation. The percentage of alcohol in a drink varies from 0.5 – 9.5%, depending on the method by which the alcohol is obtained. Fermentation is the process in which the yeast acts on sugar and converts it to ethanol and gives off carbon dioxide. The fermented liquid has 3-14% alcohol and it can be concentrated up to 95% by a series of distillations. Distillation is the process of separating elements in a liquid by vaporization and condensation. In the distillation process, the alcohol which is present in the fermented liquid (alcoholic wash) is separated from water. Classification of Alcoholic Beverages Alcoholic beverages are classified as Fermented beverages, Distilled beverages and Compound beverages. Fermented Beverages Fermented beverages can be divided into two groups, wines and beers, broadly defined. Wines are fermented from various fruit juices containing fermentable sugars. Beers come from starch-containing products, which undergo enzymatic splitting by diastase, malting, and mashing, before the fermentable sugars become available for the yeasts and bacteria. -

Observations on the Microbial Ecology of Traditional Alcoholic Cider Storage Vats

encourage native gray ant populations and reduce southern fire ant abun- dance is needed. K.M. Daane is Associate Specialist, Cen- ter for Biological Control, Division ofln- sect Biology, Department of ESPM, UC Berkeley (stationed at the Kearney Agri- cultural Center in Parlier); and 1.W. Dlott is Senior Researcher, Dlott t3 Associates Consulting, Santa Cruz. We would like to thank Paul Buxman and Dick and Karen Peterson for use of their farms; the Califor- nia Clean Growers Association for help in Commercial production of pear cider the development of grower-collaborative would create an alternative market for research; Andy Gutierrez and Charlie pears. The champagne method results in Summers for helpful suggest ions; Matt the highest quality beverage. Graduate Jones, Ingrid Peterson and Glenn Yokota students Christopher Scarlata and Sally Johnson gradually riddle the bottles to for laboratory and fieldwork; and the Cali- collect the yeast sediment in a small plas- fornia Tree Fruit Agreement, California tic cup behind the crown cap. Cling Peach Board, California Energy Commission, and Switzer Foundation En- vironmental Fellowship for funding. Feasibility of producing pear wine . References Barnett WW, Edstrom JP, Coviello RL, Zalom FG. 1993. Insect pathogen Bt controls peach twig borer on fruits and almonds. Cal Pears produce premium Ag 47(5):4-6. Daane KM, Johnson RS, Michailides TJ, et al. 1995. Nitrogen fertilization affects nec- sparkling wine tarine fruit yield, storage qualities, and sus- ceptibility to brown rot and insect damage. Cal Ag 49(4):13-8. Glenn T. McGourty 0 Christian E. Butzke Daane KM, Yokota GY, Dlott JW. -

International Wine Review Reports on the Wines of Mount

The International Wine Review January/February 2016 Report #54: The Wines of Mount Veeder Introduction In this Issue Introduction ..................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ......................................................... 2 History ............................................................................ 3 Geography, Soils and Climate ....................................... 5 The Mount Veeder Vineyard ........................................ 6 Wines and Winemaking ............................................ 10 View from the Lagier Meredith Vineyard Summary ................................................................................ 11 Winery Profiles & Tasting Notes ................................ 13 The largest of five mountain AVAs in Napa Valley, Mount Veeder is located along the cool southern ridges of the Annex: Mount Veeder Appellation Map .................... 22 Mayacamas Mountains that run between Napa Valley and Sonoma County. Its 25 square miles of rare natural beauty and diversity have attracted a small contingent of indepen- dent spirits, rugged individualist farmers with true passion to produce outstanding wines. Indeed, over the past 175 years, winegrowers of this majestic region have demon- strated unique determination to farm this mountain land- scape where many had thought growing conditions were too difficult. Today, Mount Veeder is the source of some of Napa Valley’s finest wines, and they are getting better and Syrah and Cabernet Sauvignon. However, it -

A Comprehensive History of Beer Brewing 1

1 1 A Comprehensive History of Beer Brewing Franz G. Meussdoerffer 1.1 Introduction Brewing has been a human activity ever since the beginning of urbanization and civilization in the Neolithic period. Beer is a product valued by its physico - chemical properties (i.e. quality) as much as by its entanglement with religious, culinary and ethnic distinctiveness (i.e. tradition). Accordingly, the history of beer brewing is not only one of scientifi c and technological advancement, but also the tale of people themselves: their governance, their economy, their rites and their daily life. It encompasses grain markets as well as alchemy. There exists a vast literature on beer and brewing. Among the most comprehen- sive reviews are the books by Arnold [1] and Hornsey [2] . Some aspects have recently been covered by Unger [3] and Nelson [4] . A major problem is posed by language – there is an abundance of information available in, for instance, English, German, Dutch, French, Danish or Czech, which, due to insuffi cient command of the various languages, is are not acknowledged by other authors. If evaluated in a broader context these publications would yield very interesting insights. There are two fundamental limits to any history of beer brewing. First of all it is the unambiguous defi nition of its object, namely beer. Does ‘ beer ’ broadly refer to fermented beverages based on grain or does it designate the hopped drink obtained from liquefi ed starch after fermentation with specifi c strains of Saccha- romyces yeasts, which is understood to be beer in our times? Although including the history of all grain - based fermented beverages would exceed the scope of this chapter, a consideration of hopped beer only would be too selective, and would ignore the fundamental roots of brewing technology and beer culture. -

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2020) Revision 15 Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2020) Revision 15 Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes CHAPTER 22 BEVERAGES, SPIRITS AND VINEGAR IV 22-1 Notes 1. This chapter does not cover: (a) Products of this chapter (other than those of heading 2209) prepared for culinary purposes and thereby rendered unsuitable for consumption as beverages (generally heading 2103) (b) Sea water (heading 2501); (c) Distilled or conductivity water or water of similar purity (heading 2853); (d) Acetic acid of a concentration exceeding 10 percent by weight of acetic acid (heading 2915); (e) Medicaments of heading 3003 or 3004; or (f) Perfumery or toilet preparations (chapter 33). 2. For the purposes of this chapter and of chapters 20 and 2l, the "alcoholic strength by volume" shall be determined at a temperature of 20°C. 3. For the purposes of heading 2202 the term "nonalcoholic beverages" means beverages of an alcoholic strength by volume not exceeding 0.5 percent vol. Alcoholic beverages are classified in headings 2203 to 2206 or heading 2208 as appropriate. Subheading Note 1. For the purposes of subheading 2204.10 the expression "sparkling wine" means wine which, when kept at a temperature of 20°C in closed containers, has an excess pressure of not less than 3 bars. Additional U.S. Notes 1. The duties prescribed on products covered by this chapter are in addition to the internal-revenue taxes imposed under existing law or any subsequent act. The duties imposed on products covered by this chapter which are subject also to internal-revenue taxes are imposed only on the quantities subject to such taxes; except that, in the case of distilled spirits transferred to the bonded premises of a distilled spirits plant under the provisions of section 5232 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954, the duties are imposed on the quantity withdrawn from customs custody. -

BCH Beverage Menu

CIDER CATCHING Join in the Basque tradition of txotx or cider catching from our 80 year old chestnut barrels from Asturias, Spain. 8 / per catch BROOKLYN CIDER HOUSE DRAFT 8oz pours/bottle KINDA DRY 7/17 Semi-sweet, tart apple, sparkling 5.5% abv HALF SOUR 7/17 Pickled pear, wild flower, honey, sparkling 5.8% abv BONE DR Y 8/22 Super dry, crisp, mineral, sparkling 6.9% abv RAW 7/17 Dry, sour, funky (wild fermented), still 6.9% abv TAKE BROOKLYN CIDER ROSE 7 Fruity, bubbly, off-dry, notes of rose petal, HOUSE HOME wild raspberries and sour cherries 5.8% Save a bottle for later, give the gift of cider, or abv stock up for your next party. Ask your server SOLSTICE *LIMITED RELEASE 8/22 or stop by anytime to grab some Brooklyn Wild fermented & dry, lychee, Cider House hard cider to go. Mix & Match! pineapple, lemon zest 6% abv SINGLE BOTTLE 3-PACK CASE OF 12 MO *LIMITED RELEASE 8/22 MAIN LINE CIDERS 10 29 108 STILL BONE DRY *LIMITED RELEASE 8/22 BONE DRY 39 144 Super dry, still, unfiltered (natural cider). 14 Zesty and racy. SOLSTICE 6.8% abv 14 39 144 THREE 3 OZ POUR FLIGHTS 11 off-dry: Half Sour, Ros, kinda dry STILL BONE DRY 14 39 144 dry: still bone dry, Mo, Raw, build your own: choose any three house ciders OTHER CIDER SOUTH HILL "POMM SUR LIE" 8 KITE & STRING - NORTHERN SPY 29 Still, Dry, barrel aged, tannic, acidic, apple skin, roasted nuts Semi-dry. Charmat method.