ASTR 2310: Chapter 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REVIEW ARTICLE the NASA Spitzer Space Telescope

REVIEW OF SCIENTIFIC INSTRUMENTS 78, 011302 ͑2007͒ REVIEW ARTICLE The NASA Spitzer Space Telescope ͒ R. D. Gehrza Department of Astronomy, School of Physics and Astronomy, 116 Church Street, S.E., University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455 ͒ T. L. Roelligb NASA Ames Research Center, MS 245-6, Moffett Field, California 94035-1000 ͒ M. W. Wernerc Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, MS 264-767, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, California 91109 ͒ G. G. Faziod Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 ͒ J. R. Houcke Astronomy Department, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853-6801 ͒ F. J. Lowf Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, 933 North Cherry Avenue, Tucson, Arizona 85721 ͒ G. H. Riekeg Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, 933 North Cherry Avenue, Tucson, Arizona 85721 ͒ ͒ B. T. Soiferh and D. A. Levinei Spitzer Science Center, MC 220-6, California Institute of Technology, 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, California 91125 ͒ E. A. Romanaj Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, MS 264-767, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, California 91109 ͑Received 2 June 2006; accepted 17 September 2006; published online 30 January 2007͒ The National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Spitzer Space Telescope ͑formerly the Space Infrared Telescope Facility͒ is the fourth and final facility in the Great Observatories Program, joining Hubble Space Telescope ͑1990͒, the Compton Gamma-Ray Observatory ͑1991–2000͒, and the Chandra X-Ray Observatory ͑1999͒. Spitzer, with a sensitivity that is almost three orders of magnitude greater than that of any previous ground-based and space-based infrared observatory, is expected to revolutionize our understanding of the creation of the universe, the formation and evolution of primitive galaxies, the origin of stars and planets, and the chemical evolution of the universe. -

Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer Launch Press

PRess KIT/DECEMBER 2009 Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer Launch Contents Media Services Information ................................................................................................................. 3 Quick Facts ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Mission Overview .................................................................................................................................. 5 Why Infrared? ....................................................................................................................................... 10 Science Goals and Objectives ......................................................................................................... 12 Spacecraft ............................................................................................................................................. 16 Science Instrument ............................................................................................................................. 19 Infrared Missions: Past and Present ............................................................................................... 23 NASA’s Explorer Program ................................................................................................................. 25 Program/Project Management .......................................................................................................... 27 Media Contacts J.D. Harrington -

UV and Infrared Astronomy

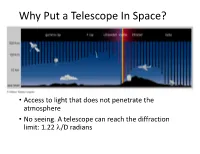

Why Put a Telescope In Space? • Access to light that does not penetrate the atmosphere • No seeing. A telescope can reach the diffraction limit: 1.22 l/D radians Astronomy in Space. I. UV Astronomy Ultraviolet Astronomy 912-3650 Å (Lyman Limit to Balmer jump) • Continuua of hot stars (spectral types O,B,A) • H I Lyman lines (1-n transitions) • Resonance lines of Li-like ions C IV, N V, O VI • H2 Lyman and Werner bands Normal incidence optics • Special UV-reflective coatings The Far Ultraviolet 912 to 1150 Å • Defined by Lyman limit, MgF cutoff at 1150 Å • LiF + Al reflects longward of 1050 Å • SiC reflects at shorter wavelengths The Astronomy Quarterly, Vol. 7, pp. 131-142, 1990 0364-9229f90 $3.00+.00 Printed in the USA. All rights reserved. Copyright (c) 1990 Pergamon Press plc ASTRONOMICAL ADVANTAGES History OFAN • 9/1/1946: Lyman Spitzer EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL OBSERVATORY proposed a Space Telescope in LYMAN SPITZER, Jr. ’ a Report to project Rand This study points out, in a very preliminary way, the results that might be expected from astronomical measurements made with a satellite • 1966: Spitzer (Princeton) vehicle. The discussion is divided into three parts, corresponding to three different assumptions concerning the amount of instrumentation provided. chairs NASA Ad Hoc In the first section it is assumed that no telescope is provided; in the second a 10-&h reflector is assumed; in the third section some of the results Committee on the "Scientific obtainable with a large reflecting telescope, many feet in diameter, and revolving about the earth above the terrestrial atmosphere, are briefly Uses of the Large Space sketched. -

The Spitzer Space Telescope and the IR Astronomy Imaging Chain

Spitzer Space Telescope (A.K.A. The Space Infrared Telescope Facility) The Infrared Imaging Chain Fundamentals of Astronomical Imaging – Spitzer Space Telescope – 8 May 2006 1/38 The infrared imaging chain Generally similar to the optical imaging chain... 1) Source (different from optical astronomy sources) 2) Object (usually the same as the source in astronomy) 3) Collector (Spitzer Space Telescope) 4) Sensor (IR detector) 5) Processing 6) Display 7) Analysis 8) Storage ... but steps 3) and 4) are a bit more difficult! Fundamentals of Astronomical Imaging – Spitzer Space Telescope – 8 May 2006 2/38 The infrared imaging chain Longer wavelength – need a bigger telescope to get the same resolution or put up with lower resolution Fundamentals of Astronomical Imaging – Spitzer Space Telescope – 8 May 2006 3/38 Emission of IR radiation Warm objects emit lots of thermal infrared as well as reflecting it Including telescopes, people, and the Earth – so collection of IR radiation with a telescope is more complicated than an optical telescope Optical image of Spitzer Space Telescope launch: brighter regions are those which reflect more light IR image of Spitzer launch: brighter regions are those which emit more heat Infrared wavelength depends on temperature of object Fundamentals of Astronomical Imaging – Spitzer Space Telescope – 8 May 2006 4/38 Atmospheric absorption The atmosphere blocks most infrared radiation Need a telescope in space to view the IR properly Fundamentals of Astronomical Imaging – Spitzer Space Telescope – 8 May 2006 5/38 -

Paul Hertz NASA Town Hall with Bonus Material

Paul Hertz Dominic Benford Felicia Chou Valerie Connaughton Lucien Cox Jeanne Davis Kristen Erickson Daniel Evans Michael Garcia Ellen Gertsen Shahid Habib Hashima Hasan Douglas Hudgins Patricia Knezek Elizabeth Landau William Latter Michael New Mario Perez Gregory Robinson Rita Sambruna Evan Scannapieco Kartik Sheth Eric Smith Eric Tollestrup NASA Town Hall with bonus material AAS 235th Meeting | January 5, 2020 Paul Hertz Director, Astrophysics Division Science Mission Directorate @PHertzNASA Posted at http://science.nasa.gov/astrophysics/documents 1 2 Spitzer 8/25/2003 Formulation + SMEX/MO (2025), Implementation MIDEX/MO (2028), etc. Primary Ops ] Extended Ops SXG (RSA) 7/13/2019 Webb Euclid (ESA) 2021 WFIRST 2022 Mid 2020s Ariel (ESA) 2028 XMM-Newton Chandra (ESA) TESS 7/23/1999 12/10/1999 4/18/2018 NuSTAR 6/13/2012 Fermi IXPE Swift 6/11/2008 2021 11/20/2004 XRISM (JAXA) SPHEREx 2022 2023 Hubble ISS-NICER GUSTO 4/24/1990 6/3/2017 2021 SOFIA Full Ops 5/2014 + Athena (early 2030s), Revised November 24, 2019 LISA4 (early 2030s) Outline • Celebrate Accomplishments § Mission Milestones • Committed to Improving § Building an Excellent Workforce § Research and Analysis Initiatives • Program Update § Research & Analysis, Technology, Fellowships § ROSES-2020 Preview • Missions Update § Operating Missions and Senior Review § Webb, WFIRST § Other missions • Planning for the Future § FY20 Budget § Project Artemis § Supporting Astro2020 § Creating the Future 5 NASA Astrophysics Celebrate Accomplishments https://www.nasa.gov/2019 7 NASA Astrophysics -

The Space Infrared Interferometric Telescope (SPIRIT): High- Resolution Imaging and Spectroscopy in the Far-Infrared

Leisawitz, D. et al., J. Adv. Space Res., in press (2007), doi:10.1016/j.asr.2007.05.081 The Space Infrared Interferometric Telescope (SPIRIT): High- resolution imaging and spectroscopy in the far-infrared David Leisawitza, Charles Bakera, Amy Bargerb, Dominic Benforda, Andrew Blainc, Rob Boylea, Richard Brodericka, Jason Budinoffa, John Carpenterc, Richard Caverlya, Phil Chena, Steve Cooleya, Christine Cottinghamd, Julie Crookea, Dave DiPietroa, Mike DiPirroa, Michael Femianoa, Art Ferrera, Jacqueline Fischere, Jonathan P. Gardnera, Lou Hallocka, Kenny Harrisa, Kate Hartmana, Martin Harwitf, Lynne Hillenbrandc, Tupper Hydea, Drew Jonesa, Jim Kellogga, Alan Koguta, Marc Kuchnera, Bill Lawsona, Javier Lechaa, Maria Lechaa, Amy Mainzerg, Jim Manniona, Anthony Martinoa, Paul Masona, John Mathera, Gibran McDonalda, Rick Millsa, Lee Mundyh, Stan Ollendorfa, Joe Pellicciottia, Dave Quinna, Kirk Rheea, Stephen Rineharta, Tim Sauerwinea, Robert Silverberga, Terry Smitha, Gordon Staceyf, H. Philip Stahli, Johannes Staguhn j, Steve Tompkinsa, June Tveekrema, Sheila Walla, and Mark Wilsona a NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD b Department of Astronomy, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, USA c California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA d Lockheed Martin Technical Operations, Bethesda, Maryland, USA e Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, DC, USA f Department of Astronomy, Cornell University, Ithaca, USA g Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA h Astronomy Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, USA i NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama, USA j SSAI, Lanham, Maryland, USA ABSTRACT We report results of a recently-completed pre-Formulation Phase study of SPIRIT, a candidate NASA Origins Probe mission. SPIRIT is a spatial and spectral interferometer with an operating wavelength range 25 - 400 µm. -

Special Spitzer Telescope Edition No

INFRARED SCIENCE INTEREST GROUP Special Spitzer Telescope Edition No. 4 | August 2020 Contents From the IR SIG Leadership Council In the time since our last newsletter in January, the world has changed. 1 From the SIG Leadership Travel restrictions and quarantine have necessitated online-conferences, web-based meetings, and working from home. Upturned semesters, constantly shifting deadlines and schedules, and the evolving challenge of Science Highlights keeping our families and communities safe have all taken their toll. We hope this newsletter offers a moment of respite and a reminder that our community 2 Mysteries of Exoplanet continues its work even in the face of great uncertainty and upheaval. Atmospheres In January we said goodbye to the Spitzer Space Telescope, which 4 Relevance of Spitzer in the completed its mission after sixteen years in space. In celebration of Spitzer, Era of Roman, Euclid, and in recognition of the work of so many members of our community, this Rubin & SPHEREx newsletter edition specifically highlights cutting edge science based on and inspired by Spitzer. In the words of Dr. Paul Hertz, Director of Astrophysics 6 Spitzer: The Star-Formation at NASA: Legacy Lives On "Spitzer taught us how important infrared light is to our 8 AKARI Spitzer Survey understanding of our universe, both in our own cosmic 10 Science Impact of SOFIA- neighborhood and as far away as the most distant galaxies. HIRMES Termination The advances we make across many areas in astrophysics in the future will be because of Spitzer's extraordinary legacy." Technical Highlights Though Spitzer is gone, our community remains optimistic and looks forward to the advances that the next generation of IR telescopes will bring. -

Spitzer Space Telescope

Implementing Portals of the Universe: Lessons Learned Spitzer Space Telescope Lisa Storrie-Lombardi Spitzer Science Center, Manager & Asst. Director for Community Affairs Basic Parameters Mission Duration: 8+ years: year 3 of Warm +5.5 yr Cryogenic Mission Userbase: international, thousands Archive Data Volume: > 50 TB, tens of millions of data files Instruments: Warm Mission -- IRAC 3.6 and 4.5 micron imaging Cryogenic Mission: IRAC (3.6 – 8 micron imaging), MIPS (24, 70, 160 micron imaging+ SED mode), IRS (5-40 micron spec. +16 micron imaging) Program Model: 100% GO time for Warm Mission Cryogenic Mission: 80-85% GO, 15-20% GTO + Archive & Theory programs Proposals/Cycle: Warm Mission 150-200 (by design) Cryogenic Mission: 650 – 850 Users: >8,000 PI/CoIs for mission (10% unique), 20% PIs new in Cycle-8 53 Legacy/Exploration Science programs have engaged community in new way Legacy program was pioneered by Spitzer with input from community task force Funding model: Formulaic data analysis funding Warm Mission: $5-10m/cycle GO funding 7000 – 8000 hours/year Cryogenic mission: $20-25m/cycle GO funding 6000 – 6500 hours/year Default proprietary data period: Exploration Science (80% of Warm Mission hrs) – no proprietary period Cryogenic mission – Legacy programs also had zero proprietary period Regular GO programs – 1 year Implementing Portals of the Universe -- 25 April 2012 SPITZER SPACE TELESCOPE 1 Best Practices Implementing Portals of the Universe -- 25 April 2012 SPITZER SPACE TELESCOPE 2 Highlight #1: Major Mission Evolution is Possible* -

Making the Invisible Visible: a History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003)/ by Renee M

MAKING THE INVISIBLE A History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003) MONOGRAPHS IN AEROSPACE HISTORY, NO. 47 Renee M. Rottner MAKING THE INVISIBLE VISIBLE A History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003) MONOGRAPHS IN AEROSPACE HISTORY, NO. 47 Renee M. Rottner National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Communications NASA History Division Washington, DC 20546 NASA SP-2017-4547 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rottner, Renee M., 1967– Title: Making the invisible visible: a history of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003)/ by Renee M. Rottner. Other titles: History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003) Description: | Series: Monographs in aerospace history; #47 | Series: NASA SP; 2017-4547 | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2012013847 Subjects: LCSH: Spitzer Space Telescope (Spacecraft) | Infrared astronomy. | Orbiting astronomical observatories. | Space telescopes. Classification: LCC QB470 .R68 2012 | DDC 522/.2919—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2012013847 ON THE COVER Front: Giant star Zeta Ophiuchi and its effects on the surrounding dust clouds Back (top left to bottom right): Orion, the Whirlpool Galaxy, galaxy NGC 1292, RCW 49 nebula, the center of the Milky Way Galaxy, “yellow balls” in the W33 Star forming region, Helix Nebula, spiral galaxy NGC 2841 This publication is available as a free download at http://www.nasa.gov/ebooks. ISBN 9781626830363 90000 > 9 781626 830363 Contents v Acknowledgments -

NASA Shutting Down Space Telescope, Infrared Eyes to Cosmos 29 January 2020, by Marcia Dunn

NASA shutting down space telescope, infrared eyes to cosmos 29 January 2020, by Marcia Dunn put the aging spacecraft into permanent hibernation. For years, Spitzer peered through dusty clouds at untold stars and galaxies, uncovered a huge, nearly invisible ring around Saturn, and helped discover seven Earth-size planets around a nearby star. Spitzer's last observation was expected Wednesday. Altogether, Spitzer observed 800,000 celestial targets and churned out more than 36 million raw images as part of the $1.4 billion mission. An estimated 4,000 scientists around the world took part in the observations and published nearly 9,000 studies, according to NASA. "You have to be proud ... when you look back and say, 'Look at the team that's operating Spitzer, look at the team that's contributing to having all of this great science,' " said project manager Joseph This composite image made available by NASA shows a Hunt. neutron star, center, left behind by the explosion from the original star's death in the constellation Taurus, Designed to last just 2.5 years to five years, the observed on Earth as the supernova of A.D. 1054. This telescope got increasingly difficult to operate as it image uses data from three of NASA's observatories: drifted farther behind Earth, NASA said. It currently the Chandra X-ray image is shown in blue, the Hubble trails Earth by 165 million miles (265 million Space Telescope optical image is in red and yellow, and the Spitzer Space Telescope's infrared image is in kilometers), while orbiting the sun. -

NASA Budget Update

NASA Astrophysics Update Astronomy and Astrophysics Advisory Committee Telecon Meeting June 3, 2019 Paul Hertz Director, Astrophysics Division Science Mission Directorate @PHertzNASA Astrophysics Strategic Planning To be updated in 2019 Astro2020 Decadal Survey (per GPRAMA) underway 2018 update includes: • Independent reviews of Webb & WFIRST • Planning for 2020 Decadal Survey https://science.nasa.gov/astrophysics/documents 2 NASA Astrophysics Budget Update 3 FY20 Budget Request The FY20 President’s Budget Request requests a decreased level of funding for NASA Astrophysics. Total funding requested for FY20 (Astrophysics including Webb) is ~1.197B, a decrease of $187M (14%) from the FY18 appropriation and a decrease of $299M (20%) from the FY19 appropriation. https://nasa.gov/budget 4 FY20 President’s Budget Request for Astrophysics including Webb Telescope What’s Changed • Webb budget increased consistent with 2018 replan, Webb proceeding toward launch in 2021 • Probe program deferred to fund Webb replan • SPHEREx begun within Explorers program as next Astrophysics MIDEX • SOFIA mission funded beyond end of 5-year prime mission in 2019, details pending 2019 independent reviews • Provides no funding for WFIRST space telescope What’s the Same • Cadence of four Explorer and Mission of Opportunity AOs per decade • Spitzer ends operations January 2020 per 2016 Senior Review • Phase A studies of Small Explorers (SMEX) and Missions of Opportunity from 2019 AO • IXPE, GUSTO, XRISM, and Euclid development remains on track and within budget • Hubble, -

Observatories in Space

OBSERVATORIES IN SPACE Catherine Turon GEPI-UMR CNRS 8111, Observatoire de Paris, Section de Meudon, 92195 Meudon, France Keywords: Astronomy, astrophysics, space, observations, stars, galaxies, interstellar medium, cosmic background. Contents 1. Introduction 2. The impact of the Earth atmosphere on astronomical observations 3. High-energy space observatories 4. Optical-Ultraviolet space observatories 5. Infrared, sub-millimeter and millimeter-space observatories 6. Gravitational waves space observatories 7. Conclusion Summary Space observatories are having major impacts on our knowledge of the Universe, from the Solar neighborhood to the cosmological background, opening many new windows out of reach to ground-based observatories. Celestial objects emit all over the electromagnetic spectrum, and the Earth’s atmosphere blocks a large part of them. Moreover, space offers a very stable environment from where the whole sky can be observed with no (or very little) perturbations, providing new observing possibilities. This chapter presents a few striking examples of astrophysics space observatories and of major results spanning from the Solar neighborhood and our Galaxy to external galaxies, quasars and the cosmological background. 1. Introduction Observing the sky, charting the places, motions and luminosities of celestial objects, elaborating complex models to interpret their apparent positions and their variations, and figure out the position of the Earth – later the Solar System or the Galaxy – in the Universe is a long-standing activity of mankind. It has been made for centuries from the ground and in the optical wavelengths, first measuring the positions, motions and brightness of stars, then analyzing their color and spectra to understand their physical nature, then analyzing the light received from other objects: gas, nebulae, quasars, etc.