Figure 1: South Richmond Shoreline Study Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution and Abundance

DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE IN RELATION TO HABITAT AND LANDSCAPE FEATURES AND NEST SITE CHARACTERISTICS OF CALIFORNIA BLACK RAIL (Laterallus jamaicensis coturniculus) IN THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY ESTUARY FINAL REPORT To the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service March 2002 Hildie Spautz* and Nadav Nur, PhD Point Reyes Bird Observatory 4990 Shoreline Highway Stinson Beach, CA 94970 *corresponding author contact: [email protected] PRBO Black Rail Report to FWS 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY We conducted surveys for California Black Rails (Laterallus jamaicensis coturniculus) at 34 tidal salt marshes in San Pablo Bay, Suisun Bay, northern San Francisco Bay and western Marin County in 2000 and 2001 with the aims of: 1) providing the best current information on distribution and abundance of Black Rails, marsh by marsh, and total population size per bay region, 2) identifying vegetation, habitat, and landscape features that predict the presence of black rails, and 3) summarizing information on nesting and nest site characteristics. Abundance indices were higher at 8 marshes than in 1996 and earlier surveys, and lower in 4 others; with two showing no overall change. Of 13 marshes surveyed for the first time, Black Rails were detected at 7 sites. The absolute density calculated using the program DISTANCE averaged 2.63 (± 1.05 [S.E.]) birds/ha in San Pablo Bay and 3.44 birds/ha (± 0.73) in Suisun Bay. At each survey point we collected information on vegetation cover and structure, and calculated landscape metrics using ArcView GIS. We analyzed Black Rail presence or absence by first analyzing differences among marshes, and then by analyzing factors that influence detection of rails at each survey station. -

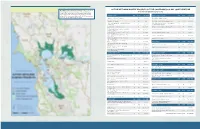

Active Wetland Habitat Projects of the San

ACTIVE WETLAND HABITAT PROJECTS OF THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY JOINT VENTURE The SFBJV tracks and facilitates habitat protection, restoration, and enhancement projects throughout the nine Bay Area Projects listed Alphabetically by County counties. This map shows where a variety of active wetland habitat projects with identified funding needs are currently ALAMEDA COUNTY MAP ACRES FUND. NEED MARIN COUNTY (continued) MAP ACRES FUND. NEED underway. For a more comprehensive list of all the projects we track, visit: www.sfbayjv.org/projects.php Alameda Creek Fisheries Restoration 1 NA $12,000,000 McInnis Marsh Habitat Restoration 33 180 $17,500,000 Alameda Point Restoration 2 660 TBD Novato Deer Island Tidal Wetlands Restoration 34 194 $7,000,000 Coyote Hills Regional Park - Restoration and Public Prey enhancement for sea ducks - a novel approach 3 306 $12,000,000 35 3.8 $300,000 Access Project to subtidal habitat restoration Hayward Shoreline Habitat Restoration 4 324 $5,000,000 Redwood Creek Restoration at Muir Beach, Phase 5 36 46 $8,200,000 Hoffman Marsh Restoration Project - McLaughlin 5 40 $2,500,000 Spinnaker Marsh Restoration 37 17 $3,000,000 Eastshore State Park Intertidal Habitat Improvement Project - McLaughlin 6 4 $1,000,000 Tennessee Valley Wetlands Restoration 38 5 $600,000 Eastshore State Park Martin Luther King Jr. Regional Shoreline - Water 7 200 $3,000,000 Tiscornia Marsh Restoration 39 16 $1,500,000 Quality Project Oakland Gateway Shoreline - Restoration and 8 200 $12,000,000 Tomales Dunes Wetlands 40 2 $0 Public Access Project Off-shore Bird Habitat Project - McLaughlin 9 1 $1,500,000 NAPA COUNTY MAP ACRES FUND. -

Chapter 4.9 Land Use and Planning

Section 4.9 Land Use and Planning 4.9 LAND USE AND PLANNING 4.9.1 Introduction This section evaluates the potential land use and planning impacts of development under the 2014 LRDP. The planned 2014 LRDP land uses are described and assessed for potential conflicts with existing RBC site and surrounding land uses and land use plans. Public and agency NOP comments related to land use and planning are summarized below: The EIR should consider proposed new building heights and massing in terms of compatibility with surrounding uses. The EIR should consider 2014 LRDP compatibility with the Eastshore State Park General Plan goals and policies. The 2014 LRDP should conform to local zoning and approved local land use policies to the maximum extent feasible. These comments are considered in the analysis below. 4.9.2 Environmental Setting Project Site The approximately 134-acre RBC site is in the City of Richmond, approximately 5 miles northwest of the UC Berkeley campus and the LBNL site in Berkeley (see Figure 3-1). The City of Richmond is in Contra Costa County. The RBC site is bounded on the west by a PG&E service station, on the northwest by Regatta Boulevard, on the northeast by Meade Street, on the east by South 46th Street, and on the south by the San Francisco Bay. I-580 runs parallel to Meade Street along the northeastern boundary of the RBC site. Existing On-Site Land Uses The RBC site has been the location of a variety of industrial enterprises dating back to the mid- 19th century. -

Point Isabel

bulldozed as fl at as a pancake, which greatly El Cerrito Historical Society expanded the P O Box 304, El Cerrito, CA 94530 footprint of Pt. Isabel. (This and [email protected] several other projects around the Bay helped Vol. 24 create support for Summer 2008 Shooting trap (l) and an archery “Ham Shoot” (r) at the MacAteer-Pe- No. 3 The Forge the San Pablo Avenue Sportsman’s Club on Pt. Isabel tris Act of 1965, The Offi cial Publication of the El Cerrito Historical Society, Copyright © 2008 which established the BCDC, or Bay Conservation and Development Commission). Santa Fe, of course, built a rail spur to the development to provide a direct connection to their transcontinen- tal mainline. Once these preparations were complete, Santa Fe sat back and waited for the buyers OUR NEXT MEETING: 12 NOON SUNDAY, JULY 20TH to line up. However, the fi rst lot was not sold until 1963, when the old Co-op grocery store chain PICNIC AT HUBER PARK ON TERRACE DRIVE bought a lot for a large warehouse it needed. In the early 1970s the Postal Service chose the site for the huge bulk mail facility that still operates today. A condition of the building permit for the bulk mail facility was that the Federal Government President’s Message had to provide shoreline access for the public. Once the public saw the fantastic vistas available Our next meeting, at Noon on Sunday, July 20th in Huber Park, will be our annual pot- from the shoreline the popularity of the area grew rapidly. -

Vegetation Ofthe Hoffman Marsh

Vegetation of the Hoffman Marsh Post Restoration of 1984 Walter Alexander Introduction Hoffman Marsh is an intertidal salt marsh, located in the southern-most part of the City of Richmond (Figure 1). The 40-acre Marsh is part of the original Bay margin. Such areas as this are rare, because over 85 per cent of the Bay's marshes and tidal flats have been filled In over the last hundred years. Hoffman Marsh has also experienced modifications due to landfilling around its perimeter. Construction of a dike to support a sewer line resulted in the isolation of the southern portion of the Marsh (Figure 2). This southern section, the "study site," is the area on which I will focus my study. The remaining portion of the Marsh, the "main marsh," is connected to San Francisco Bay by a 15-foot wide channel inlet. The channel provides Due to state and federal law requiring legal compensation or "mitigation" for the development of environmentally significant land, the California Department of Transportation (CalTrans) in 1984 did some restoration work in the southern portion (study site) of the Hoffman Marsh, as compensation for the widening of Highway 17 (now 1-580) (Craig, 1985). The restoration was intended to increase water circulation through the study site. Because of unforeseen problems, only portions of the restoration project were completed. Craig (1985) studied the vegetation in the southern part of the Marsh prior to the rehabilitation project. My study will be a follow up to Craig's. By identifying the species present today and calculating their frequency, I hope to identify the changes, if any. -

Control Calendar (PDF

2007 San Francisco Estuary Invasive Spartina Control Program Schedule Updated: 9/14/07 More information on: Treatment methods Imazapyr Site Locations Treatment Location Treatment Method (gray areas denote sites where treatment was not planned this year or was completed) Imazapyr Herbicide Manual Sub-Area Amphibious Aerial: Aerial: Spray Covering with Manual Site # Site Name Sub-Area Name County Treatment date Truck Backpack Boat Excavation Number vehicle Broadcast Ball Geotextile Fabric Digging 01a Channel Mouth Alameda 7/31-8/2/07 XX 01b Lower Channel (not including mouth) Alameda 7/31-8/2/07 XX 01c Upper Channel Alameda 7/31-8/2/07 Alameda Flood Control XX 1 Upper Channel - Union City Blvd to I- Channel 01d Alameda 7/23-7/27/07 XX 880 01e Strip Marsh No. of Channel Mouth Alameda 7/31-8/2/07 X 01f Pond 3-AFCC Alameda 7/31-8/2/07 XX Belmont Slough/Island, North Point, 02a Bird Island, Steinberger Slough/ San Mateo 9/10-9/13/07 XX Redwood Shores Steinberger Slough South, Corkscrew 02b San Mateo 7/31-8/2/07 XXX Slough, Redwood Creek North 02c B2 North Quadrant San Mateo 7/31-8/2/07 XX 02d B2 South Quadrant - Rookery San Mateo 7/31-8/2/07 X 2 Bair/Greco Islands 02e West Point Slough NW San Mateo 7/31-8/2/07 XX 02f Greco Island North San Mateo 7/31-8/2/07 X 02g West Point Slough SW and East San Mateo 8/27- 8/30/07 XX 02h Greco Island South San Mateo 7/31-8/2/07 X 02i Ravenswood Slough & Mouth San Mateo 7/31-8/2/07 XX 02j Ravenswood Open Space Preserve San Mateo 9/10-9/13/07 X 03a Blackie's Creek (above bridge) Marin 8/29/07 X 3 Blackie's -

Restoring the Estuary

1 AA FrameworkFramework forfor CollaborativeCollaborative ActionAction onon WetlandsWetlands US FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE etlands in the San Francisco Bay Area are range of interests—including resource and regulato- Wamong the most important coastal wintering ry agencies, environmental organizations, business, and migratory stopover areas for millions of water- and agriculture—convened the San Francisco Bay fowl and shorebirds traveling along the Pacific Fly- Joint Venture (SFBJV) in June of 1995. In September way, which stretches from Alaska to South America. 1996, 20 parties representing this diverse wetlands These wetlands also provide economic benefits, constituency signed a working agreement that iden- offer a range of recreational opportunities, and con- tified the goals and objectives of the SFBJV, and the tribute to a higher quality of life for residents in the responsibilities of its board and working commit- densely populated San Francisco Bay Area. They are tees. The agreement also stated that the Implemen- essential aspects of the Bay region’s unique charac- tation Strategy would be developed to guide its par- ter and, along with the creeks that flow into the Bay, ties toward the long-term vision of the restored Bay help to define the vibrant and distinctive identities Estuary. The signatory partners recognized and of communities around the Bay. However, despite endorsed the goals of the North American Waterfowl their value, destruction of these precious natural Management Plan. However, they enlarged the goals assets continues. Today’s wetlands are only a rem- and objectives of the Plan to include benefits not nant, perhaps 20 percent of the vast wetlands seen only for waterfowl, but also for the other wildlife by the first European settlers. -

Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals a Report of Habitat Recommendations

Baylands Ecosystem Baylands Ecosystem Teams of Bay Area environmental scientists have assessed abitat Goals the past and present conditions of the baylands ecosystem and recommended ways to improve its ecological health. This report presents the Baylands Ecosystem Goals. Habitat Goals Habitat Goals H A Report of Habitat Recommendations Prepared by the San Francisco Bay Area Wetlands Ecosystem Goals Project Db Deep Bay/Channel Basic Baylands Facts Sb Shallow Bay/Channel The baylands exist around the Bay between the lines of high and Tf Tidal Flat low tide. They are the lands touched by the tides, plus the lands that Tm Tidal Marsh the tides would touch in the absence of any levees or other unnat- Tp Tidal Marsh Pan ural structures. Lg Lagoon There are 73,000 acres of tidal baylands and 139,000 acres of diked Bc Beach/Dune baylands. Ag Agricultural Bayland There used to be 23 miles of sandy beaches. Now there are about Dw Diked Wetland seven miles of beaches. Most of the present beaches occur in differ- Sp Salt Pond ent locations than the historical beaches. St Storage or Treatment Pond There used to be 190,000 acres of tidal marsh with 6,000 miles of Uf Undeveloped Bay Fill channels and 8,000 acres of shallow pans. Now there are 40,000 Df Developed Bay Fill acres of tidal marsh with about 1,000 miles of channels and 250 Pr Perennial Pond acres of pans. Rw Riparian Forest/Willow Grove Only 16,000 acres of the historical tidal marsh remain. The rest of Mg Moist Grassland the present tidal marsh has naturally evolved from tidal flat, been Gr Grassland/Vernal Pool Complex restored from diked baylands, or muted by water control structures. -

Coastal Resilience Assessment of the San Francisco Bay and Outer Coast Watersheds

Coastal Resilience Assessment of the San Francisco Bay and Outer Coast Watersheds Suggested Citation: Crist, P.J., S. Veloz, J. Wood, R. White, M. Chesnutt, C. Scott, P. Cutter, and G. Dobson. Coastal Resilience Assessment of the San Francisco Bay and Outer Coast Watersheds. 2019. National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. IMPORTANT INFORMATION/DISCLAIMER: This report represents a Regional Coastal Resilience Assessment that can be used to identify places on the landscape for resilience-building efforts and conservation actions through understanding coastal flood threats, the exposure of populations and infrastructure have to those threats, and the presence of suitable fish and wildlife habitat. As with all remotely sensed or publicly available data, all features should be verified with a site visit, as the locations of suitable landscapes or areas containing flood hazards and community assets are approximate. The data, maps, and analysis provided should be used only as a screening-level resource to support management decisions. This report should be used strictly as a planning reference tool and not for permitting or other legal purposes. The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government, or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s partners. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation or its funding sources. NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION DISCLAIMER: The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of NOAA or the Department of Commerce. -

California Clapper Rail (Rallus Longirostris Obsoletus) Population Monitoring: 2005-2011 Final Technical Report

California Clapper Rail (Rallus longirostris obsoletus) Population monitoring: 2005-2011 Final Technical Report Leonard Liu, Julian Wood, Nadav Nur, Leo Salas, and Dennis Jongsomjit PRBO Conservation Science 3820 Cypress Drive #11, Petaluma, CA 94954 California Clapper Rail Population Monitoring 2005-2011 Final Report Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 6 METHODS .............................................................................................................. 9 FIELD SURVEYS .................................................................................................................... 9 ANALYSES ......................................................................................................................... 10 MODEL APPROACH ............................................................................................................. 11 ECOLOGICAL MODEL ........................................................................................................... 11 Detection Sub-model. ............................................................................................................................. 11 Abundance Sub-model. ......................................................................................................................... -

Vegetation of the Hoffman Marsh Before the Restoration Project of 1984

r Chapter 2 VEGETATION OF THE HOFFMAN MARSH BEFORE THE RESTORATION PROJECT OF 1984 Darrin Craig Introduction With an increase in automobiles in the Bay Area, our highways must be expanded, often at the expense of open land. To make a stretch of highway 17 in the East Bay more effective by widening it, Caltrans is going to take a portion of natural mud flats in Albany. By law, land that is taken must be compen sated for by some means. As legal compensation or "mitigation" Caltrans has planned to revive an un healthy portion of a nearby salt marsh. The Hoffman Marsh in Richmond (see map, p. viii) is the location for the mitigation. A dike that supports a sewer line has cut off tidal flow to the southern portion of the marsh, which has had many adverse effects on the natural flora. To revive the marsh, Caltrans planned to enlarge the culverts through the dike in an attempt to bring normal tidal flow to the unhealthy section. Caltrans also planned to enlarge the existing channels. My study is a base-line survey of the vegetation before the rehabilitation project. With my work others will later be able to determine if Caltrans has fulfilled its obligation to restore normal tidal flow and consequently, to restore the natural flora. It is my hope that through a follow-up survey the merits of the mitigation process can be evaluated and future mitigation cases can be guided by those assessments. Background The Hoffman Marsh study site is located on the shore of San Francisco Bay (see map on p. -

Richmond Annex Neighborhood Council Founded 1974 PO Box 5436, Richmond, California 94805 *Neighbors Helping Neighbors*

Richmond Annex Neighborhood Council Founded 1974 PO Box 5436, Richmond, California 94805 *Neighbors Helping Neighbors* MONTHLY GENERAL MEETING Board of Directors : Thursday, July 28, 2011 Mary Selva LOCATION: Annex Senior Center, 5801 Huntington @ Santa Clara President STARTING TIME: 7:00 PM SHARP Garland Ellis (Length of time per agenda item is only approximate; more time allotted if necessary.) 1st Vice President 1. Call to order : Pledge of Allegiance; welcome and introductions; announcements – 3 min. Jeff Jones 2nd Vice President 2. Minutes of June 30, 2011 General Monthly Meeting – 2 min. Tom Hoffman Treasurer 3. Finance Report : Tom Hoffman, Treasurer (finance report given quarterly) – 3 min. Gayle Massman 4. Board Officer announcements : Correspondence – 3 min. Recording Secretary Karen Mayers 5. Richmond Police Dept. report : Beat Officer Report: Ofc. Cedric Tagorda – 10 min. Corresponding Secretary 6. Special Guest : Bob Gerner, Owner of The El Cerrito Natural Grocery invites Members at Large : community input on commercial uses and building design of the former Sherwin Doug Bruce Williams Paint building (corner of San Pablo Avenue and Panama), that would compliment the Natural Grocery and benefit the community. Cate Burkhart Pam Challinor Chris Flynn 7. Proposed Building and Planning Projects : 10 min. ea. Linda Grant a) See above. Chip Gribble 8. In brief – Reports; project & committee updates: 5 min. ea. Tom Hannan Dave Harris a) Streets/Traffic Committee Update: I-80 Central Avenue Interchange Improvement Project; Carlson Corridor Upgrade Project, Jeff Jones, chair Pete Keown b) Planning/Zoning Committee Update: Richmond General Plan, Mary Selva, chair Andy Anderson c) Richmond Neighborhood Coordinating Council Update: Garland Ellis and Jerry Yoshida, RNCC Irene Patterson representatives and board members Vicky Propp d) 66th public meeting of the Community Advisory Group (CAG) is Thurs.