Tales of the Bay Shore -- Pt. Isabel-Stege Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2011 510 520 3876

BPWA Walks Walks take place rain or shine and last 2-3 hours unless otherwise noted. They are free and Berkeley’s open to all. Walks are divided into four types: Theme Friendly Power Self Guided Questions about the walks? Contact Keith Skinner: [email protected] Vol. 14 No. 3 BerkeleyPaths Path Wanderers Association Fall 2011 510 520 3876. October 9, Sunday - 2nd An- BPWA Annual Meeting Oct. 20 nual Long Walk - 9 a.m. Leaders: Keith Skinner, Colleen Neff, To Feature Greenbelt Alliance — Sandy Friedland Sandy Friedland Can the Bay Area continue to gain way people live.” A graduate of Stanford Meeting Place: El Cerrito BART station, University, Matt worked for an envi- main entrance near Central population without sacrificing precious Transit: BART - Richmond line farmland, losing open space and harm- ronmental group in Sacramento before All day walk that includes portions of Al- ing the environment? The members of he joined Greenbelt. His responsibilities bany Hill, Pt. Isabel, Bay Trail, Albany Bulb, Greenbelt Alliance are doing everything include meeting with city council members East Shore Park, Aquatic Park, Sisterna they can to answer those questions with District, and Santa Fe Right-of-Way, ending a resounding “Yes.” Berkeley Path at North Berkeley BART. See further details Wanderers Asso- in the article on page 2. Be sure to bring a ciation is proud to water bottle and bag lunch. No dogs, please. feature Greenbelt October 22, Saturday - Bay Alliance at our Trail Exploration on New Landfill Annual Meeting Thursday, October Loop - 9:30 a.m. 20, at the Hillside Club (2286 Cedar Leaders: Sandra & Bruce Beyaert. -

Priority Conservation Area Grant Program

COASTAL CONSERVANCY Staff Recommendation October 17, 2019 PRIORITY CONSERVATION AREA GRANT PROGRAM ROUND 2 Project Manager: Brenda Buxton RECOMMENDED ACTION: Recommend to the Metropolitan Transportation Commission that sixteen resource protection and public access projects be included in the Priority Conservation Area Grant Program. LOCATION: Counties of Alameda, Contra Costa, Santa Clara, San Mateo, and San Francisco PROGRAM CATEGORY: San Francisco Bay Area Conservancy EXHIBITS Exhibit 1: Project Location Map Exhibit 2: Priority Conservation Area Grant Program Call for Proposals RESOLUTION AND FINDINGS: Staff recommends that the State Coastal Conservancy adopt the following resolution pursuant to Section 31160-31165 of the Public Resources Code: “The State Coastal Conservancy hereby recommends to the Metropolitan Transportation Commission that the following projects (in geographic order) and recommended grant amounts totaling $7,397,000 be included in the Priority Conservation Area Grant Program: 1. One million dollars ($1,000,000) to the City of Richmond to construct a 1.25-mile, Class 1 segment of the San Francisco Bay Trail connecting Point Molate Beach Park to the Winehaven Historic District in Contra Costa County. 2. One million dollars ($1,000,000) to East Bay Regional Park District to construct a 1.25- mile, Class 1 segment of the San Francisco Bay Trail connecting the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge to Point Molate Beach Park in Contra Costa County. 3. Nine hundred fifty thousand dollars ($950,000) to the John Muir Land Trust for construction of trails, bridges, overlooks and other public access amenities as part of the Pacheco Marsh (Lower Walnut Creek) Restoration Project in Contra Costa County. -

Lepidoptera of Albany Hill, Alameda Co., California

LEPIDOPTERA OF ALBANY HILL, ALAMEDA CO., CALIFORNIA Jerry A. Powell Essig Museum of Entomology University of California, Berkeley and Robert L. Langston Kensington, CA November 1999; edited 2009 The following list summarizes observations of Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) at Albany Hill, Alameda Co., California, during 1995-1999. Data originate from about 75 daytime and crepuscular visits of 0.5 to 3.5 hrs, in all months of the year. All of the butterfly species and some of the moths were recorded by RLL, most of the moth species and their larval host plants by JAP. A total of 145 species is recorded (30 butterflies, 115 moths), a modest number considering the extent and diversity of the flora. However, many of the potential larval host plants may be present in too small patches to support populations of larger moths or butterflies. Nonetheless, we were surprised that colonies of some of the species survive in a small area that has been surrounded by urban development for many decades, including some rare ones in the East Bay region, as annotated below. Moreover, the inventory is incomplete. A more comprehensive census would be accomplished by trapping moths attracted to ultraviolet lights. In a habitat of this size, however, such survey would attract an unknown proportion of species from surrounding areas. Larval collections are indicated by date-based JAP lot numbers (e.g. 95C37 = 1995, March, 37th collection). Larval foods of most of the other species are documented in other populations. Host plants are recorded at Albany Hill for 75 species (65% of the moths, 52% of the total); the rest were observed as adults only. -

Distribution and Abundance

DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE IN RELATION TO HABITAT AND LANDSCAPE FEATURES AND NEST SITE CHARACTERISTICS OF CALIFORNIA BLACK RAIL (Laterallus jamaicensis coturniculus) IN THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY ESTUARY FINAL REPORT To the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service March 2002 Hildie Spautz* and Nadav Nur, PhD Point Reyes Bird Observatory 4990 Shoreline Highway Stinson Beach, CA 94970 *corresponding author contact: [email protected] PRBO Black Rail Report to FWS 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY We conducted surveys for California Black Rails (Laterallus jamaicensis coturniculus) at 34 tidal salt marshes in San Pablo Bay, Suisun Bay, northern San Francisco Bay and western Marin County in 2000 and 2001 with the aims of: 1) providing the best current information on distribution and abundance of Black Rails, marsh by marsh, and total population size per bay region, 2) identifying vegetation, habitat, and landscape features that predict the presence of black rails, and 3) summarizing information on nesting and nest site characteristics. Abundance indices were higher at 8 marshes than in 1996 and earlier surveys, and lower in 4 others; with two showing no overall change. Of 13 marshes surveyed for the first time, Black Rails were detected at 7 sites. The absolute density calculated using the program DISTANCE averaged 2.63 (± 1.05 [S.E.]) birds/ha in San Pablo Bay and 3.44 birds/ha (± 0.73) in Suisun Bay. At each survey point we collected information on vegetation cover and structure, and calculated landscape metrics using ArcView GIS. We analyzed Black Rail presence or absence by first analyzing differences among marshes, and then by analyzing factors that influence detection of rails at each survey station. -

Contra Costa County

Historical Distribution and Current Status of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California Robert A. Leidy, Environmental Protection Agency, San Francisco, CA Gordon S. Becker, Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA Brett N. Harvey, John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, CA This report should be cited as: Leidy, R.A., G.S. Becker, B.N. Harvey. 2005. Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration CONTRA COSTA COUNTY Marsh Creek Watershed Marsh Creek flows approximately 30 miles from the eastern slopes of Mt. Diablo to Suisun Bay in the northern San Francisco Estuary. Its watershed consists of about 100 square miles. The headwaters of Marsh Creek consist of numerous small, intermittent and perennial tributaries within the Black Hills. The creek drains to the northwest before abruptly turning east near Marsh Creek Springs. From Marsh Creek Springs, Marsh Creek flows in an easterly direction entering Marsh Creek Reservoir, constructed in the 1960s. The creek is largely channelized in the lower watershed, and includes a drop structure near the city of Brentwood that appears to be a complete passage barrier. Marsh Creek enters the Big Break area of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta northeast of the city of Oakley. Marsh Creek No salmonids were observed by DFG during an April 1942 visual survey of Marsh Creek at two locations: 0.25 miles upstream from the mouth in a tidal reach, and in close proximity to a bridge four miles east of Byron (Curtis 1942). -

4 Infrastructure Systems Infrastructure Analysis Contents 4.01 INTRODUCTION 04-1

4 Infrastructure Systems Infrastructure Analysis Contents 4.01 INTRODUCTION 04-1 4.02 STORM DRAINAGE SYSTEM 04-2 4.02.01 GENERAL 04-2 4.02.02 SUPPLY AND CAPACITY 04-2 4.02.03 RUNOFF PATTERNS 04-2 4.02.04 RATIO OF PERVIOUS TO IMPERVIOUS AREA 04-3 4.02.05 DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS 04-3 4.02.06 RECOMMENDED IMPROVEMENTS 04-4 4.03 WATER SYSTEM 04-6 4.03.01 EXISTING CONDITIONS 04-6 4.03.02 RECOMMENDED IMPROVEMENTS 04-6 4.04 SANITARY SEWER SYSTEM 04-8 4.04.01 EXISTING CONDITIONS 04-8 4.04.02 RECOMMENDED IMPROVEMENTS 04-8 4.05 DRY UTILITIES 04-11 4.05.01 PG&E GAS LINE LOCATION 04-11 4.05.02 PG&E ELECTRIC LINE LOCATION 04-11 4.05.03 CABLE, INTERNET, AND TELECOM ACCESS 04-11 4.06 REFERENCES 04-12 04.ii - San Pablo Avenue Specific Plan - August, 2014 - Corrected Infrastructure Analysis Table of Figures Infrastructure Figure 01. Impermeable surfaces are widespread in the study area 04-5 Infrastructure Figure 04. Low impact development features may serve as community amenities. 04-5 Infrastructure Figure 02. Award wining low impact streetscape improvements along San Pablo Ave 04-5 Infrastructure Figure 03. Green roof is a good stormwater best management practise. 04-5 Infrastructure Figure 05. Permeable paving, used for the parking spaces at right, is an example of LID 04-5 San Pablo Avenue Specific Plan - August, 2014 - Corrected - 04.iii Infrastructure Analysis List of Tables Infrastructure Table 01. Buildout Planning Horizon: Additional Water Demands and Associated Distribution System Improvements 04-7 Infrastructure Table 02. -

Board Meeting Packet

June 1, 2021 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Board Meeting Packet SPECIAL NOTICE REGARDING PUBLIC PARTICIPATION AT THE EAST BAY REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING SCHEDULED FOR TUESDAY, JUNE 1, 2021 at 1:00 pm Pursuant to Governor Newsom’s Executive Order No. N-29-20 and the Alameda County Health Officer’s Shelter in Place Orders, the East Bay Regional Park District Headquarters will not be open to the public and the Board of Directors and staff will be participating in the Board meetings via phone/video conferencing. Members of the public can listen and view the meeting in the following way: Via the Park District’s live video stream which can be found at https://youtu.be/md2gdzkkvVg Public comments may be submitted one of three ways: 1. Via email to Yolande Barial Knight, Clerk of the Board, at [email protected]. Email must contain in the subject line public comments – not on the agenda or public comments – agenda item #. It is preferred that these written comments be submitted by Monday, May 31, 2021 at 3:00 pm. 2. Via voicemail at (510) 544-2016. The caller must start the message by stating public comments – not on the agenda or public comments – agenda item # followed by their name and place of residence, followed by their comments. It is preferred that these voicemail comments be submitted by Monday, May 31, 2021 at 3:00 pm. 3. Live via zoom. If you would like to make a live public comment during the meeting this option is available through the virtual meeting platform: *Note: this virtual meeting platform link will let you into the https://zoom.us/j/94773173402 virtual meeting for the purpose of providing a public comment. -

Baxter Creek Gateway Park Restoration a Post-Project Appraisal

Baxter Creek Gateway Park Restoration A Post-project appraisal University of California, Berkeley LD ARCH 227 - Restoration of Rivers and Streams By: Yiwen Chen Yuanshuo Pi Dec 16, 2019 1 Abstract This paper is seeking to evaluate the results of the Baxter Creek Gateway Restoration Project located in an urbanized section of Baxter Creek, northern El Cerrito, California, and figure out how the channel transforms and how it impacts the site and its surroundings. We appraisal the project by the condition of the creek bed and bank, vegetation, water management and public accessibility. Making a comparison of 2006 and 2019 status of the creek to figure out how the stream performed and transformed in the last 13 years. Moreover, depending on the analysis of the water catchment area, planting evolvement, space quality to study the impact of the project for the surrounding area. In the end, we devote to discuss the possibilities of improvement of the site by studying other similar precedents, trying to explore the future design directions of river restoration projects. 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Site location & History Baxter Creek Gateway Restoration project is located in El Cerrito (Figure 1.1.1). The site is located on 1.6 acres of land and is 700 feet long, consisting of a branch of one of the three tributaries of Baxter Creek (Figures 1.1.2 and 1.1.3). [1] The City of El Cerrito hired Hanford Applied Restoration Conservation contractors in 2005 to restore the creek and construct a new civic gathering area facing San Pablo Ave. -

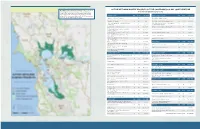

Active Wetland Habitat Projects of the San

ACTIVE WETLAND HABITAT PROJECTS OF THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY JOINT VENTURE The SFBJV tracks and facilitates habitat protection, restoration, and enhancement projects throughout the nine Bay Area Projects listed Alphabetically by County counties. This map shows where a variety of active wetland habitat projects with identified funding needs are currently ALAMEDA COUNTY MAP ACRES FUND. NEED MARIN COUNTY (continued) MAP ACRES FUND. NEED underway. For a more comprehensive list of all the projects we track, visit: www.sfbayjv.org/projects.php Alameda Creek Fisheries Restoration 1 NA $12,000,000 McInnis Marsh Habitat Restoration 33 180 $17,500,000 Alameda Point Restoration 2 660 TBD Novato Deer Island Tidal Wetlands Restoration 34 194 $7,000,000 Coyote Hills Regional Park - Restoration and Public Prey enhancement for sea ducks - a novel approach 3 306 $12,000,000 35 3.8 $300,000 Access Project to subtidal habitat restoration Hayward Shoreline Habitat Restoration 4 324 $5,000,000 Redwood Creek Restoration at Muir Beach, Phase 5 36 46 $8,200,000 Hoffman Marsh Restoration Project - McLaughlin 5 40 $2,500,000 Spinnaker Marsh Restoration 37 17 $3,000,000 Eastshore State Park Intertidal Habitat Improvement Project - McLaughlin 6 4 $1,000,000 Tennessee Valley Wetlands Restoration 38 5 $600,000 Eastshore State Park Martin Luther King Jr. Regional Shoreline - Water 7 200 $3,000,000 Tiscornia Marsh Restoration 39 16 $1,500,000 Quality Project Oakland Gateway Shoreline - Restoration and 8 200 $12,000,000 Tomales Dunes Wetlands 40 2 $0 Public Access Project Off-shore Bird Habitat Project - McLaughlin 9 1 $1,500,000 NAPA COUNTY MAP ACRES FUND. -

Pt. Isabel-Stege Area

Tales of the Bay Shore -- Pt. Isabel-Stege area Geology: The “bones” of the shoreline from Albany to Richmond are a sliver of ancient, alien sea floor, caught on the edge of North America as it overrode the Pacific. Fleming Point (site of today’s racetrack), Albany Hill, Pt. Isabel, Brooks Island, scattered hillocks inland, the hills at Pt Richmond, and the hills across the San Pablo Strait (spanned by the Richmond Bridge) all are part of this Novato Terrane. Erosion and uplift eventually left their hard rock as hilltops in a valley. Still later – only about 5000 years ago -- rising seas from the melting glaciers of our last Ice Age flooded the valley, forming today’s San Francisco Bay. The “alien” hilltops became islands, peninsulas linked to shore by marsh, or isolated dome-like “turtlebacks.” Left: Portion of 1911 map of SF Bay showing many Native American sites near Pt. Isabel and Stege. Right: 1853 U.S. Coastal Survey map showing N. end of Albany Hill, Cerrito Creek, Pt. Isabel, and marshes/ to North. Native Americans: Native Americans would have watched the slow rise of today’s Bay. When Europeans reached North America, the East Bay was the home of Huchiun Ohlone peoples. Living in groups generally of fewer than 100 people, they moved seasonally amid rich and varied resources, gathering, hunting, fishing, and encouraging useful plants with pruning and burning. They made reed boats, baskets, nets, traps, mortars, and a wide variety of implements and decorations. Along the shellfish-rich shoreline they gradually built up substantial hills of debris – shell mounds -- that kept them above floods and served as multipurpose homesites, burial sites, refuse dumps, and more. -

Climate Change Adaptation Study APPENDIX

City of Richmond Climate Change Adaptation Study APPENDIX City of Richmond Climate Action Plan Appendix F: Climate Change Adaptation Study Acknowledgements The City of Richmond has been an active participant in the Contra Costa County Adapting to Rising Tides Project, led by the Bay Conservation Development Commission (BCDC) in partnership with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the State Coastal Conservancy, the San Francisco Estuary Partnership, the San Francisco Estuary Institute, Alameda County Flood Control and Water Conservation District and the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, and consulting firm AECOM. Environmental Science Associates (ESA) completed this Adaptation Study in coordination with BCDC, relying in part on reports and maps developed for the Adapting to Rising Tides project to assess the City of Richmond’s vulnerabilities with respect to sea level rise and coastal flooding. City of Richmond Climate Action Plan F-i Appendix F: Climate Change Adaptation Study This page intentionally left blank F-ii City of Richmond Climate Action Plan Appendix F: Climate Change Adaptation Study Table of Contents Acknowledgements i 1. Executive Summary 1 1.1 Coastal Flooding 2 1.2 Water Supply 2 1.3 Critical Transportation Assets 3 1.4 Vulnerable Populations 3 1.5 Summary 3 2. Study Methodology 4 2.1 Scope and Organize 4 2.2 Assess 4 2.3 Define 4 2.4 Plan 5 2.5 Implement and Monitor 5 3. Setting 6 3.1 Statewide Climate Change Projections 6 3.2 Bay Area Region Climate Change Projections 7 3.3 Community Assets 8 3.4 Relevant Local Planning Initiatives 9 3.5 Relevant State and Regional Planning Initiatives 10 4. -

Community Participation and Creek Restoration in the East Bay of San Francisco

Louise A. Mozingo Community Participation and Creek Restoration and Recreation, had been inspired by an article of Bay Area Community Participation and historian Grey Brechin on the possibilities of daylighting creeks Creek Restoration in the East in Sonoma County north of San Francisco (Schemmerling, 2003). Doug Wolfe, a landscape architect for the City of Bay of San Francisco Berkeley, proposed that a short culverted stretch of Strawberry Creek crossing a new neighborhood park in Berkeley then culverted, be opened or “daylit.” As a first step in proposing Louise A. Mozingo the unprecedented idea, Wolfe named the new open space Strawberry Creek Park. As he later reported, this “lead to the ABSTRACT question ‘Where is this creek?’ My answer was that it was ‘Twenty feet down and waiting’” (Wolfe, 1994, 2). Controversial The creeks of the upper East Bay of San Francisco in the extreme, Wolfe found political support from Carol have been the location of two decades of precedent Schemmerling, and David Brower, founder of Friends of the setting creek restoration activities. This discussion will Earth, and a city council member. With vocal citizen support review the essential role of both citizen activism and at public meetings the radical concept prevailed. The notion NGOs in the advent of a restoration approach to creek that a reopened creek could be an asset rather than a hazard management. Beginning with small pilot projects to proved to be a lasting inspiration (Schemmerling; Wolfe, 2-3). “daylight” a culverted creek and spray paint signs on street drain inlets, participation in the restoration of the Also in Berkeley, a small but telling community education act East Bay creeks has evolved into a complex layering took place on city streets.