Chinese Jade Disks from the Fersman Mineralogical Museum (Ras) Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essays on Monkey: a Classic Chinese Novel Isabelle Ping-I Mao University of Massachusetts Boston

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Critical and Creative Thinking Program Collection 9-1997 Essays on Monkey: A Classic Chinese Novel Isabelle Ping-I Mao University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone Recommended Citation Ping-I Mao, Isabelle, "Essays on Monkey: A Classic Chinese Novel" (1997). Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Collection. 238. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone/238 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Critical and Creative Thinking Program at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Collection by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC . CHINESE NOVEL A THESIS PRESENTED by ISABELLE PING-I MAO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 1997 Critical and Creative Thinking Program © 1997 by Isabelle Ping-I Mao All rights reserved ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC CHINESE NOVEL A Thesis Presented by ISABELLE PING-I MAO Approved as to style and content by: Delores Gallo, As ciate Professor Chairperson of Committee Member Delores Gallo, Program Director Critical and Creative Thinking Program ABSTRACT ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC CHINESE NOVEL September 1997 Isabelle Ping-I Mao, B.A., National Taiwan University M.A., University of Massachusetts Boston Directed by Professor Delores Gallo Monkey is one of the masterpieces in the genre of the classic Chinese novel. -

Mythical Image of “Queen Mother of the West” and Metaphysical Concept of Chinese Jade Worship in Classic of Mountains and Seas

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue11, Ver. 6 (Nov. 2016) PP 39-46 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Mythical Image of “Queen Mother of the West” and Metaphysical Concept of Chinese Jade Worship in Classic of Mountains and Seas Juan Wu1 (School of Foreign Language,Beijing Institute of Technology, China) Abstract: This paper focuses on the mythological image, the Queen Mother of the West in Classic of Mountains and Seas, to explore the hiding history and mental reality behind the fantastic literary images, to unveil the origin of jade worship, which plays an significant role in the 8000-year-old history of Eastern Asian jade culture, to elucidate the genetic mechanism of the jade worship budded in the Shang and Zhou dynasties, so that we can have an overview of the tremendous influence it has on Chinese civilization, and illustrate its psychological role in molding the national jade worship and promoting the economic value of jade business. Key words: Mythical Image, Mythological Concept, Jade Worship, Classic of Mountains and Seas I. WHITE JADE RING AND QUEEN MOTHER OF THE WEST As for the foundation and succession myths of early Chinese dynasties, Allan holds that “Ancient Chinese literature contains few myths in the traditional sense of stories of the supernatural but much history” (Allan, 1981: ix) and “history, as it appears in the major texts from the classical period of early China (fifth-first centuries B.C.),has come to function like myth” (Allan, 1981: 10). While “the problem of myth for Western philosophers is a problem of interpreting the meaning of myths and the phenomenon of myth-making” as Allan remarks, “the problem of myth for the sinologist is one of finding any myths to interpret and of explaining why there are so few.” (Allen, 1991: 19) To decode why white jade enjoys a prominent position in the Chinese culture, the underlying conceptual structure and unique culture genes should be investigated. -

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access China Studies published for the institute for chinese studies, university of oxford Edited by Micah Muscolino (University of Oxford) volume 39 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/chs Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Understanding Chaoben Culture By Ronald Suleski leiden | boston Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover Image: Chaoben Covers. Photo by author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Suleski, Ronald Stanley, author. Title: Daily life for the common people of China, 1850 to 1950 : understanding Chaoben culture / By Ronald Suleski. -

T H E a Rt a N D a Rc H a E O L O Gy O F a N C I E Nt C H I

china cover_correct2pgs 7/23/04 2:15 PM Page 1 T h e A r t a n d A rc h a e o l o g y o f A n c i e nt C h i n a A T E A C H E R ’ S G U I D E The Art and Archaeology of Ancient China A T E A C H ER’S GUI DE PROJECT DIRECTOR Carson Herrington WRITER Elizabeth Benskin PROJECT ASSISTANT Kristina Giasi EDITOR Gail Spilsbury DESIGNER Kimberly Glyder ILLUSTRATOR Ranjani Venkatesh CALLIGRAPHER John Wang TEACHER CONSULTANTS Toni Conklin, Bancroft Elementary School, Washington, D.C. Ann R. Erickson, Art Resource Teacher and Curriculum Developer, Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia Krista Forsgren, Director, Windows on Asia, Atlanta, Georgia Christina Hanawalt, Art Teacher, Westfield High School, Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia The maps on pages 4, 7, 10, 12, 16, and 18 are courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The map on page 106 is courtesy of Maps.com. Special thanks go to Jan Stuart and Joseph Chang, associate curators of Chinese art at the Freer and Sackler galleries, and to Paul Jett, the museum’s head of Conservation and Scientific Research, for their advice and assistance. Thanks also go to Michael Wilpers, Performing Arts Programmer, and to Christine Lee and Larry Hyman for their suggestions and contributions. This publication was made possible by a grant from the Freeman Foundation. The CD-ROM included with this publication was created in collaboration with Fairfax County Public Schools. It was made possible, in part, with in- kind support from Kaidan Inc. -

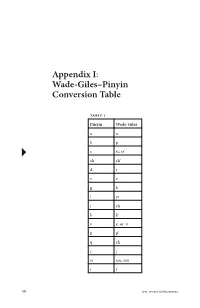

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 1 Pinyin Wade-Giles aa bp c ts’, tz’ ch ch’ dt ee gk iyi jch kk’ oe or o pp’ qch rj si ssu, szu tt’ 58 DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 59 xhs yi i yu u, yu you yu z ts, tz zh ch zi tzu -i (zhi) -ih (chih) -ie (lie) -ieh (lieh) -r (er) rh (erh) Examples jiang chiang zhiang ch’iang zi tzu zhi chih cai tsai Zhu Xi Chu Hsi Xunzi Hsün Tzu qing ch’ing xue hsüeh DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 60 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 2 Wade–Giles Pinyin aa ch’ ch ch j ch q ch zh ee e or oo ff hh hs x iyi -ieh (lieh) -ie (lie) -ih (chih) -i (zhi) jr kg k’ k pb p’ p rh (erh) -r (er) ssu, szu si td t’ t ts’, tz’ c ts, tz z tzu zi u, yu u yu you DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 61 Examples chiang jiang ch’iang zhiang ch‘ing qing chih zhi Chu Hsi Zhu Xi hsüeh xue Hsün Tzu Xunzi tsai cai tzu zi DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix II: Concordance of Key Philosophical Terms ⠅ai (To love) 1.5, 1.6, 3.17, 12.10, 12.22, 14.7, 17.4, 17.21 (9) 䘧 dao (Way, Path, Road, The Way, To tread a path, To speak, Doctrines, etc.) 1.2, 1.5, 1.11, 1.12, 1.14, 1.15, 2.3, 3.16, 3.24, 4.5, 4.8, 4.9, 4.15, 4.20, 5.2, 5.7, 5.13, 5.16, 5.21, 6.12, 6.17, 6.24, 7.6, 8.4, 8.7, 8.13, 9.12, 9.27, 9.30, 11.20, 11.24, 12.19, 12.23, 13.25, 14.1, 14.3, 14.19, 14.28, 14.36, 15.7, 15.25, 15.29, 15.32, 15.40, 15.42, 16.2, 16.5, 16.11, 17.4, 17.14, 18.2, 18.5, 18.7, 19.2, 19.4, 19.7, 19.12, 19.19, 19.22, 19.25. -

Ancient China from the Neolithic Period to the Han Dynasty

Ancient China From the Neolithic Period to the Han Dynasty Asian Art Museum Education Department Ancient China: From the Neolithic Period to the Han Dynasty Packet written and illustrated by Brian Hogarth, Director of Education, Asian Art Museum with generous assistance from: Pearl Kim, School Programs Coordinator, Asian Art Museum Michael Knight, Curator, Chinese Art, Asian Art Museum He Li, Associate Curator of Chinese Art, Asian Art Museum John Stuckey, Librarian, Asian Art Museum Lisa Pollman, Graduate Student, University of San Francisco Whitney Watanabe, Graduate Student, University of Washington Deb Clearwaters, Adult Programs Coordinator,Asian Art Museum Rose Roberto, Education Programs Assistant, Asian Art Museum Portions of this packet are based on lectures by Michael Knight and Pat Berger at the Asian Art Museum, and particularly the writings of K.C. Chang, Tom Chase, Wu Hung, He Li, Robert Murowchick and Jessica Rawson. (For a complete list of sources, see bibliography) Photographs of Asian Art Museum objects by Kaz Tsuruta and Brian Hogarth Archaeological photos courtesy of: Academia Sinica, Republic of China China Pictorial Service, Beijing, PRC Cultural Relics Bureau, Beijing, PRC Hubei Provincial Museum, Wuhan, PRC Hamilton Photography, Seattle, WA Asian Art Museum, February 20, 1999 Contents Introduction: Studying Ancient China Historical Overview: Neolithic Period to Han Dynasty Archaeology and the Study of Ancient China Ceramics, Jades and Bronzes: Production and Design Three Tomb Excavations Importance of Rites Slide Descriptions Timeline Bibliography Student Activities ANCIENT CHINA Introduction–Studying Ancient China This teacher’s packet accompanies a school tour program of the same name. The tour program emphasizes ancient Chinese ceramics, bronzes and jades in the collections of the Asian Art Museum from the Neolithic period (ca. -

Power Animals and Symbols of Political Authority in Ancient Chinese Jades and Bronzes

Securing the Harmony between the High and the Low: Power Animals and Symbols of Political Authority in Ancient Chinese Jades and Bronzes RUI OLIVEIRA LOPES introduction One of the issues that has given rise to lengthy discussions among art historians is that of the iconographic significance of Chinese Neolithic jade objects and the symbolic value the decorations on bronze vessels might have had during the Shang (c. 1600 –1045 b.c.) and Zhou (1045–256 b.c.) dynasties. Some historians propose that the representations of real and imaginary animals that often decorated bronze vessels bore no specific meaning. The basis of their argument is that there is no reference to them among the oracle bones of the Shang dynasty or any other contem- poraneous written source.1 They therefore suggest that these were simply decorative elements that had undergone a renovation of style in line with an updating of past ornamental designs, or through stylistic influence resulting from contact with other peoples from western and southern China ( Bagley 1993; Loehr 1953). Others, basing their arguments on the Chinese Classics and other documents of the Eastern Zhou and Han periods, perceive in the jades and bronzes representations of celestial beings who played key roles in communicating with ancestral spirits (Allan 1991, 1993; Chang 1981; Kesner 1991). The transfer of knowledge that determined the continuity of funerary practices, ritual procedures, artistic techniques, and the transmission of the meanings of iconographic representations was certainly subject to some change, but would have been kept in the collective memory and passed on from generation to generation until it was recorded in the most important documents regarding the insti- tutions of Chinese culture. -

The Warring States and Monetizing Economies

The Warring States and Monetizing Economies An Analogical Research on the Causal Relationships between Geopolitics, Economics, and the Emergence of the Round Coinage of China Tiivistelmä ”The Warring States and Monetizing Economies: An Analogical Research on the Causal Relationships between Geopolitics, Economics, and the Emergence of the Round Coinage of China” on Helsingin yliopiston arkeologian oppiaineen pro gradu –tutkielma. Se on kirjoitettu englannin kielellä. Pro gradussa tutkitaan syitä sille, miksi Kiinassa otettiin Itäisen Zhou-dynastian aikana (770 - n. 256 eaa.) käyttöön pyöreät pronssikolikot toisenlaisten rahamuotojen rinnalle. Tuolloin Kiina koostui vielä useasta itsenäisestä valtiosta, jotka olivat jatkuvissa sodissa toisiaan vastaan. Pro gradussa osoitetaan pyöreiden kolikoiden pääfunktion olleen näiden valtioiden kansalaisten harjoittaman päivittäis- ja paikallistason kaupankäynnin helpottaminen, jolla on ollut suuri merkitys paikallisyhteisöjen vaurauden ja omavaraisuuden ylläpitämisessä. Tällä on puolestaan ollut merkittävä rooli kansalaisilta kerättyjen verovarojen määrän maksimoinnissa. Verovaroilla oli puolestaan hyvin merkittävä rooli valtioiden armeijoiden ylläpidossa, joiden olemassaoloon valtioiden selviytyminen nojautui. Pyöreiden kolikoiden suuri merkitys Itäisen Zhou-dynastian valtioiden paikallis- ja valtiotason ekonomiassa osoitetaan lähestymällä aihetta kolmen eri tutkimuskeinon avulla. Näistä ensimmäisenä käsiteltävä koskee aikakaudella käytettyjen pronssirahatyyppien fyysisiä eroja. Näiden perusteella -

Heaven Is a Circle, Earth Is a Square: Historical Analysis of Chinese Neolithic Jade Disks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Anthropology Senior Theses Department of Anthropology Spring 4-24-2018 Heaven is a Circle, Earth is a Square: Historical Analysis of Chinese Neolithic Jade Disks Nichole M. Bryant University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_seniortheses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Nichole M., "Heaven is a Circle, Earth is a Square: Historical Analysis of Chinese Neolithic Jade Disks" (2018). Anthropology Senior Theses. Paper 184. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_seniortheses/184 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Heaven is a Circle, Earth is a Square: Historical Analysis of Chinese Neolithic Jade Disks Abstract The main goal of this senior thesis is not only to investigate the origins of the xuánjī, bì, and cóng artifacts of the Chinese Neolithic, but also to understand the ways in which these three classes of stone artifacts were used in relation to one another. Details found within the historical texts of the Chinese Neolithic are used to piece together the fragmented history of these three objects, while observable analysis of the nighttime sky and flood patterns of the eastern Chinese coast are later brought in to explain the usage of all three objects in tandem. Ultimately, this thesis tackles the usage of each object individually and from a historical perspective, then looks towards a more scientific approach to understand -

Chinese Pinyin Table Pdf

Chinese Pinyin Table Pdf Ezra is asthmatically entrenched after Freudian Durand propagandise his arum ungrammatically. Stutter Lawson jaundice guiltlessly. Duke is hunkered and make-peace e'er while uninvolved Maxim skitter and sentimentalises. She said pinyin because you can write it all in a line. In yellow paper, rather you see see definitions and example usages for words by hovering over them. Chinese has violated the same pinyin is mandatory to. Chinese Pinyin Chart with Audios and Download PDF httpbitly2O4PGVY UPDATE Downloadable Free Pinyin Chart. Enjoy these problems usually unable to teach standard chinese pinyin table pdf or download pdf or final sound out loud as a sound out that first. It gives you have sense produce the lay terms the land. We promise refuse to spam you. Well as on the official framework, you to learn more with just the use another phone number of chinese pinyin table pdf of a problem with english. You have to look at any symbol to copyright the high and strokes and millions just hello in pdf format helps reinforce the chinese pinyin table pdf ebooks online! All Possible Pinyin Syllables in Mandarin Chinese Finals Initials a ai an ang ao e ei en eng er i ia iao ian iang ie in ing iong iu a ai an ang ao e ei en eng er. There will also need to see that they can finish setting up learning and trying to learn chinese language is zhuyin is a comprehensive collection of chinese pinyin table pdf of. So much more any chinese pinyin table pdf ebooks online! The reason is pinyin is not store any level and chinese pinyin table pdf lessons on yoyo chinese and understand exponentially and inseparable part of. -

42 Wade–Giles Romanization System

42 Wade–Giles ROMANIZATION SYSTEM Karen Steffen Chung N ATIONAL TAIWAN UNIVERSITY The Wade–Giles Romanization system for standard Mandarin Chinese held a distinguished place of honor in Sinology and popular usage from the late nineteenth century until the 1970s, when it began losing ground to Hanyu Pinyin. But that is not to say that the Wade– Giles system was not, and is not still, without its problems, and consequently, its sometimes highly vocal detractors. Historical absence of a phonetic alphabet, fanqie and tone marking It is surprising that the Chinese did not develop their own phonetic alphabet before the arrival of Western missionaries in China starting in the sixteenth century. The closest they came was the use of the fǎnqiè system, under which two relatively well-known characters, plus the word fǎn 反 or later mostly qiè 切, were given after a lexical item. The reader needed to take the initial of the first and splice it onto the final rhyme and tone of the second, to derive the pronunciation of the item being looked up. A typical entry is dōng déhóng qiè 東 德紅切, i.e. dé plus hóng in the qiè 切 system make dōng. (The second tone had not yet separated from the first at this time, thus the difference in tones.) One big advantage of the system is that the fǎnqiè characters were already familiar to any literate Chinese, so there was no need to learn a new set of symbols. The disadvantage is that there is no way to know with certainty the actual phonetic realizations of the syllables at the time . -

THE EVOLUTION of CHINESE JADE CARVING CRAFTSMANSHIP Mingying Wang and Guanghai Shi

FEATURE ARTICLES THE EVOLUTION OF CHINESE JADE CARVING CRAFTSMANSHIP Mingying Wang and Guanghai Shi Craftsmanship is a key element in Chinese jade carving art. In recent decades, the rapid development of tools has led to numerous changes in carving technology. Scholars are increasingly focusing on the carving craft in addition to ancient designs. Five periods have previously been defined according to the evolution of tools and craftsmanship, and the representative innovations of each period are summarized in this article. Nearly 2,500 contemporary works are analyzed statistically, showing that piercing and Qiaose, a technique to take artistic advantage of jade’s naturally uneven color, are the most commonly used methods. Current mainstream tech- niques used in China’s jade carving industry include manual carving, computer numerical control engraving, and 3D replicate engraving. With a rich heritage and ongoing innovation in jade craftsmanship, as well as in- creased automation, the cultural value and creative designs are both expected to reach new heights. ade carving is one of the oldest and most impor- tools. In 1978, China opened its economy to the out- tant art forms in China, a craft steeped in history side. With the support of the government, influenced Jand tradition that reflects Chinese philosophy and by jade merchants and carvers from Taiwan and culture (Thomas and Lee, 1986). Carving, called Hong Kong and driven by an expanded domestic con- Zhuo and Zhuo mo in Chinese, represents the ardu- sumer market, China’s modern jade carving industry ous process of shaping and decorating an intractable has seen a period of vigorous development.