Master's Degree Programme in Comparative International Relations Second Cycle (D.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

"Ayako" by Osamu Tezuka

www.smartymagazine.com "Ayako" by Osamu Tezuka by 28 Vignon Street #Comics Osamu Tezuka, nicknamed the " Dieu of manga ", remains one of the most important and innovative authors today with his some 700 works and his pioneering work in animation. We inaugurate this selection of authors from which we must read everything with this master who installed manga in Japanese culture, gave it its codes and explored all its genres (or almost). Whether through his unique drawing style, his talent as a narrator, his approach to the medium or his essays from animation ; Osamu Tezuka remains an essential keystone for anyone who wants to read and understand manga (in addition to enjoying reading his incredible masterpieces.) Among his greatest works are Phoenix: eleven volumes of a history spread over several centuries around the Phoenix, a divinity that accompanies humanity from its beginnings to a distant future in space. Each volume is independent (despite the common thread and the winks between the different stories) and could be a series in itself as Tezuka crystallizes the best of his talents in this work that has occupied him all his life. The Life of Buddha, tells the story of Prince Siddhartha's metamorphosis into Buddha, intertwined with a host of secondary stories that depict Asia in the 5th century BC and the ramifications of this new religion that will become so important. As for Phoenix, Tezuka plays on flash-back & flash-forward to offer us important points of view and variations on certain historical episodes. Humour is not absent from this work, which is thought-provoking without ever losing its reader. -

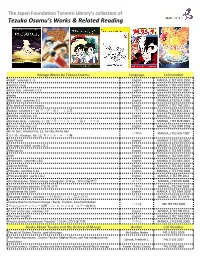

Tezuka Osamu Booklist

The Japan Foundation Toronto Library’s collection of Tezuka Osamu’s Works & Related Reading Manga Works by Tezuka Osamu Language Call number Adolf : volumes 1 - 5 English MANGA_E TEZ ADO 1995 Apollo's song English MANGA_E TEZ APO 2007 Astro boy : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ AST 2002 Ayako English MANGA_E TEZ AYA 2010 Black Jack : volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ BLA 2008 The book of human insects English MANGA_E TEZ THE 2011 Budda : volumes 1~14 ブッダ:第1-14巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUD 2011 Buddha : volumes 1-8 English MANGA_E TEZ BUD 2003 Burakku Jakku : volumes 1~22 ブラックジャック:第1-22巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUR 2004 Dororo : Volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ DOR 2008 Hi no tori : Hinotori No. 12, Girisha, Roma hen 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ HIN 1987 火の鳥 : Hinotori. No. 12, ギリシャ・ローマ編 Lost World English MANGA_E TEZ LOS 2003 Message to Adolf : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ MES 2012 Metropolis English MANGA_E TEZ MET 2003 MW English MANGA_E TEZ MW 2007 Nextworld : volumes 1 &2 English MANGA_E TEZ NEX 2003 Ode to Kirihito English MANGA_E TEZ ODE 2006 Phoenix : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ PHO 2003 Princess knight : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ PRI 2011 Shintakarajima : boken manga monogatari 新寳島 : 冒険漫画物語 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Shintakarajima tokuhon 新寶島 読本 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Swallowing the Earth English MANGA_E TEZ SWA 2009 Tetsuwan Atomu : volumes 1~17 鉄腕アトム:第 1-17 巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ TET 1979 Tezuka Osamu no Dizuni manga : Banbi, Pinokio : kara fukkokuban 日本語 REF TEZ TEZ 2005 手塚治虫のディズニー漫画 : バンビ, ピノキオ : カラー復刻版 Triton of the sea : volumes 1-2 English MANGA_E TEZ TRI 2013 The Twin Knights English MANGA_E TEZ TWI 2013 Tezuka Osamu kessakusen "kazoku"手塚治虫傑作選 家族 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ KAZ 2008 Books About Tezuka and the History of Manga Author Call Number The art of Osamu Tezuka : god of manga McCarthy, Helen 741.5 M32 2009 The Astro Boy essays : Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the manga/anime Schodt, Frederik L. -

Manga Shōnen

Manga Shnen: Kat Ken'ichi and the Manga Boys Ryan Holmberg Mechademia, Volume 8, 2013, pp. 173-193 (Article) Published by University of Minnesota Press DOI: 10.1353/mec.2013.0010 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mec/summary/v008/8.holmberg.html Access provided by University of East Anglia (12 Mar 2014 14:30 GMT) Twenty First Century Adventure, Twin Knight (Sequel to Princess Knight), Under the Air, Unico, The Vampires, Volcanic Eruption, The The Adventure of Rock, Adventure of Rubi, The Age of Adventure, The Age of Great Floods, Akebono-san, Alabaster, The Amazing 3, Ambassador Magma, Angel Gunfighter, Angel's Hill, Ant and the Giant, Apollo's Song, Apple with Watch Mechanism, Astro Boy, Ayako, Bagi, Boss of the Earth, Barbara, Benkei, Big X, Biiko-chan, Birdman Anthology, Black Jack, Bomba!, Boy Detective Zumbera, Brave Dan, Buddha, Burunga I, Captain Atom, Captain Ken, Captain Ozma, Chief Detective Kenichi, Cave-in, Crime and Punishment, The Curtain is Still Blue Tonight, DAmons, The Detective Rock Home, The Devil Garon, The Devil of the Earth, Diary of Ma-chan, Don Dracula, Dororo, Dotsuitare, Dove, Fly Up to Heaven, Dr. Mars, Dr. Thrill, Duke Goblin, Dust Eight, Elephant's Kindness, Elephant's Sneeze, Essay on Idleness of Animals, The Euphrates Tree, The Fairy of Storms, Faust, The Film Lives On, Fine Romance, Fire of Tutelary God, Fire Valley, Fisher, Flower & Barbarian, Flying Ben, Ford 32 years Type, The Fossil Island, The Fossil Man, The Fossil Man Strikes Back, Fountain of Crane, Four Card, Four Fencers of the Forest, Fuku-chan in 21st Century, Fusuke, FuturemanRYAN HOLMBERG Kaos, Gachaboi's Record of One Generation, Game, Garbage War, Gary bar pollution record, General Onimaru, Ghost, Ghost in jet base, Ghost Jungle, Ghost story at 1p.m., Gikko-chan and Makko-chan, Giletta, Go Out!, God Father's son, Gold City, Gold Scale, Golden Bat, The Golden Trunk, Good bye, Mali, Good bye, Mr. -

Manga List Sara

From top to bottom and left to right: -Photo 01: First shelf (some of my favorite collections): Manga: El Solar de los Sueños (A Patch of Dreams’s Spanish edition, Hideji Oda), Il Mondo di Coo (Coo no Sekai’s Italian edition, Hideji Oda), La Rosa de Versalles (The Rose of Versailles’s Spanish edition, Riyoko Ikeda), La Ventana de Orfeo (Orpheus no Mado’s Spanish edition, Riyoko Ikeda), Très Cher Frère (Oniisama e…’s French edition, Riyoko Ikeda), Koko (Kokkosan’s French edition, Fumiyo Kôno), Une longue route (Nagai Michi’s French edition, Fumiyo Kôno), Blue (“’s Spanish edition, Kiriko Nananan), Fruits Basket (“’s Spanish Edition, Natsuki Takaya), Fruits Basket #24: Le chat (Fruits Basket: Cat’s French edition, Natsuki Takaya), Uzumaki (“’s English edition, Junji Ito), Elegía Roja (Red Colored Elegy’s Spanish Edition, Seiichi Hayashi), Calling you (“’s Spanish edition, Otsuichi & Hiro Kiyohara), Ashita no Joe (“’s French edition, Asao Takamori & Tetsuya Chiba), Stargazing Dog (“’s English edition, Takashi Murakami), Flare: the art of Junko Mizuno (“’s “bilingual” English and Japanese edition, Junko Mizuno), Welcome to Nod·d·a·ringniche Island: Animal Encyclopedia (“’s Japanese edition, Prof. K·Sgyarma) and Fruits Basket Artbook (“’s Spanish edition, Natsuki Takaya). Postcards: two Marie Antoinettes copied by me from The Rose of Versailles, Twinkle Stars’ Spanish edition and an angel with the spiral shaped universe, from the curch of Chora, Istanbul, Turkey. Stuff: Bakugan’s ball, Alice in the Wonderland’s figurine, blue snail, Misty’s tazo, green snail, magneto with the same image than in the last postcard mentioned. -

Governs the Making of Photocopies Or Other Reproductions of Copyrighted Materials

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. University of Nevada, Reno Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Immigrants and Their Descendants in Argentine Audiovisual Popular Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Spanish and the Honors Program by Christopher A.A. Gomez May, 2014 UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA THE HONORS PROGRAM RENO We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CHRISTOPHER A.A. GOMEZ entitled Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Immigrants and Their Descendants in Argentine Audiovisual Popular Culture be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS, SPANISH ______________________________________________ Darrell B. Lockhart, Ph.D., Thesis Advisor ______________________________________________ Tamara Valentine, Ph.D., Director, Honors Program May, 2014 i Abstract For the past 40 years, immigration from China, Japan, and Korea has -

Download Ayako Free Ebook

AYAKO DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Osamu Tezuka | 704 pages | 14 Feb 2013 | Vertical Inc. | 9781935654780 | English | New York, United States Ayako tragic tale. Tezuka mercifully holds back his infamous urge to punctuate the most serious scenes with off-color comic relief, and thus this work is relentlessly Ayako by Tezukan standards; jokes are rare, gags are even rarer, and caricature is used perhaps once or twice. Oct 3 Word of the Day. She is just a hard character to Ayako ourselves into. But, just as Japan has been changing and growing over the decades since WWII, Ayako is now back in Ayako light and justice, in poetic form is coming. Ayako Edit What would you like to edit? I've liked some of Tezuka's Ayako work MetropolisAstro BoyKimba but was wary of reading Ayako post-war manga. Just like Ayako Plato's cave, Japan knew the world by its twisted shadows, Ayako only stumbled out into the light fully after WWII. View all 3 Ayako. Now the family's youngest Ayako Ayako will have Ayako bear the brunt of the family's sins. Little use of the star system of familiar characters cast in new rolls, slapstick panels and caricatures are to be found. Feb Ayako, Andrew Fairweather rated it it was amazing Shelves: asian-litcomics. It's shown that the Tenge family played a significant role in the mysterious Shimoyama renamed as the Shimokawa incident and the JNR accidents, which historically did happen. You pretty much get it all here…. A Ayako multi-layered, monumental Ayako. Feb 01, K. -

L8jwk [Download Free Ebook] Le Roi Léo, Tome 1 Online

l8jwk [Download free ebook] Le Roi Léo, tome 1 Online [l8jwk.ebook] Le Roi Léo, tome 1 Pdf Free Par Osamu Tezuka audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #909664 dans LivresPublié le: 1996-10-01Langue d'origine:FrançaisReliure: Broché170 pages | File size: 32.Mb Par Osamu Tezuka : Le Roi Léo, tome 1 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Le Roi Léo, tome 1: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Un ClassiquePar logonLe meilleur album de la série. Inventif, drôle et subtil, on ne se lasse pas de le relire même avec 15 ans de plus.0 internautes sur 1 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Un chef d'oeuvrePar Un clientUne merveille, un véritable chef d'oeuvre, alliant subtilement l'action ,l'émotion ,l'humour et le suspence. A découvrir de toute urgence... Présentation de l'éditeurDans un univers bucolique, les aventures animalières du petit Léo qui voit son père assassiné par son oncle et doit apprendre à devenir adulte pour assurer la succession du trône en tant que Roi de la jungle...Biographie de l'auteurFondateur du manga moderne, Osamu Tezuka révolutionne la bande dessinée après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, en inventant une grammaire graphique qui offre au manga des possibilités narratives aux confluents de la littérature et du cinéma. En 1946, New Treasure Island (Shin Takarajima, la Nouvelle Île au Trésor), d’après Stevenson, est le premier jalon d’une œuvre immense, sans équivalent dans la bande dessinée internationale. -

Vol. II Institutions

JAPANESE STUDIES IN THE UNITED STATES DIRECTORY OF JAPAN SPECIALISTS AND JAPANESE STUDIES INSTITUTIONS IN THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA Japanese Studies Series XXXX VOLUME II INSTITUTIONS 2013 2016 Update THE JAPAN FOUNDATION • Tokyo © 2016 The Japan Foundation 4-4-1 Yotsuya Shinjuku-ku Tokyo 160-0004 Japan All rights reserved. Written permission must be secured fronm the publisher and copyright holder to use or reproduce any part of this book. CONTENTS VOLUME I Preface The Japan Foundation ................................................................................... v Editor’s Introduction to the 2016 Update Patricia G Steinhoff .............................vii Editor’s Introduction Patricia G Steinhoff ............................................................... ix Japan Specialists in the United States and Canada ..................................................... 1 Doctoral Candidates in Japanese Studies ..................................................................791 Index of Names in Volume I ....................................................................................... 809 VOLUME II Academic Institutions with Japanese Studies Programs ............................................ 1 Other Academic Institutions with Japan Specialist Staff ....................................... 689 Non-Academic Institutions with Japanese Studies Programs .................................701 Other Non-Academic Institutions with Japan Specialist Staff ............................... 725 Index of Institutions in Volume II ............................................................................ -

Texto Completo

Japón: identidad, identidades Maria Antònia Martí Escayol LA RECEPCIÓN DE LA OBRA DE OSAMU TEZUKA EN ESPAÑA Maria Antònia Martí Escayol Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona RESUMEN En el artículo se presenta la edición de la obra de Osamu Tezuka en España desde la primera proyección en el año 1964 de un anime del autor, Arabian naito: Shindobaddo no bôken (1962). Así, se recorren seis décadas durante las cuales el espectador y el lector de manga y de anime en España ha crecido y madurado gracias al espacio crítico, teórico y editorial creado por la propia tradición del tebeo español. PALABRAS CLAVE: anime, Japón, manga, Osamu Tezuka. ABSTRACT The overall purpose of this study was to describe the production of Osamu Tezuka’s work in Spain since the first screening in 1964 of Arabian Naito: Shindobaddo no bôken (1962). We have been through six decades during which the readers and viewers of manga and anime in Spain have grown and matured through the critical, theorical and editorial space created by the Spanish comic tradition itself. KEYWORDS: anime, Japan, manga, Osamu Tezuka. LOS SESENTA. SIMBAD, ROCK Y LEO El primer contacto entre Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989) y el público español data de 1964. En este año, son 317.781 los espectadores que asisten a los cines donde se proyecta el primer anime estrenado en España con guión de Osamu Tezuka. Se trata de Simbad el marino (Arabian naito: Shindobaddo no bôken, 1962), dirigido por Taiji Yabushita, producido por Toei Animation y distribuido en España a través de Exclusivas Sánchez Ramade. El film se estrenó durante las fiestas de Navidad en veintitrés capitales simultáneamente, según datos del Ministerio de Cultura recauda un total de 40.112,01€, llega con la reputación de un primer premio conseguido en la sección de “Cine Infantil” del Festival de Venecia (1962) y es recibido con buenas 1 Japón: identidad, identidades Maria Antònia Martí Escayol críticas. -

The Interplay of Theatre and Digital Comics in Tezuka

Networking Knowledge 8(4) Digital Comics (July 2015) Performing ‘Readings’: The Interplay of Theatre And Digital Comics In Tezuka MATHIAS P. BREMGARTNER, University of Berne ABSTRACT The article investigates the intriguing interplay of digital comics and live-action elements in a detailed performance analysis of TeZukA (2011) by choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. This dance theatre production enacts the life story of Osamu Tezuka and some of his famous manga characters, interweaving performers and musicians with large-scale projections of the mangaka’s digitised comics. During the show, the dancers perform different ‘readings’ of the projected manga imagery: e.g. they swipe panels as if using portable touchscreen displays, move synchronously to animated speed lines, and create the illusion of being drawn into the stories depicted on the screen. The main argument is that TeZukA makes visible, demonstrates and reflects upon different ways of delivering, reading and interacting with digital comics. In order to verify this argument, the paper uses ideas developed in comics and theatre studies to draw more specifically on the use of digital comics in this particular performance. KEYWORDS Digital comics, manga, animation, theatre, Osamu Tezuka, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. 1 Networking Knowledge 8(4) Digital Comics (July 2015) Introduction: Theatre meets comics Over the last few years, comics have become an important cultural influence for theatre. A broad spectrum of productions draw on the plots, characters, forms of expression and aesthetics of comics. These range from commercial productions such as the arena show Batman Live and the Broadway Musical Spider-Man – Turn Off the Dark, to city and state theatre performances such as Prinz Eisenherz (Prince Valiant) and independent theatre productions such as Popeye’s Godda Blues.1 A particularly interesting performance in this context is the dance theatre production TeZukA (2011). -

Race and Identity in the Manga of Tezuka Osamu

DRAWING THE SELF: RACE AND IDENTITY IN THE MANGA OF TEZUKA OSAMU by Benjamin Evan Whaley B.A.H., Stanford University, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July 2012 © Benjamin Evan Whaley, 2012 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the construction and mutability of the Japanese race and ethnicity in the print comics of Dr. Tezuka Osamu (1928–1989), Japan’s “god of manga” and the creator of such beloved series as Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion. By investigating three of Tezuka’s mature, lesser-known works from the 1970s and 80s, I will illustrate how Tezuka’s narratives have been shaped by his consciousness of racial issues and his desire to investigate the changing nature of Japanese identity in the postwar era. First, the works are contextualized within the larger manga history of the 1960s and 70s, specifically the gekiga (lit. drama pictures) movement that heralded more mature and sophisticated stories and artwork. Chapter one analyzes Ode to Kirihito (1970–71, 2006 English), and introduces Julia Kristeva’s theory of abjection to show the ways in which Tezuka bestializes his ethnically Japanese protagonists and turns them into a distinct class of subaltern. Chapter two examines intersections between race and war narratives using Adolf (1983–85, 1995–96 English), Tezuka’s WWII epic about the Jewish Holocaust. The concept of hybridity is utilized and the case is made that Tezuka ultimately denies his racially mixed characters the benefits of their Japanese identity.