The Discovery of Neptune

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 2 License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy Author: George Biddell Airy Release Date: January 9, 2004 [EBook #10655] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR GEORGE AIRY *** Produced by Joseph Myers and PG Distributed Proofreaders AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, ASTRONOMER ROYAL FROM 1836 TO 1881. EDITED BY WILFRID AIRY, B.A., M.Inst.C.E. 1896 PREFACE. The life of Airy was essentially that of a hard-working, business man, and differed from that of other hard-working people only in the quality and variety of his work. It was not an exciting life, but it was full of interest, and his work brought him into close relations with many scientific men, and with many men high in the State. -

Kew Observatory and the Evolution of Victorian Science, 1840–1910

introduction Kew Observatory, Victorian Science, and the “Observatory Sciences” One more recent instance of the operations of this Society in this respect I may mention, in addition to those I have slightly enumerated. I mean the important accession to the means of this Society of a fixed position, a place for deposit, regula- tion, and comparison of instruments, and for many more purposes than I could name, perhaps even more than are yet contemplated, in the Observatory at Kew. Address by Lord Francis Egerton to British Association for the Advancement of Science, June 1842 When in 1842 Lord Egerton, president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS), announced the association’s acquisition of Kew Observatory (figure I.1), he heralded the inaugura- tion of what would become one of the major institutions of nineteenth- century British—indeed international—science. Originally built as a pri- vate observatory for King George III and long in a moribund state, after 1842 the Kew building would, as Egerton predicted, become a multi- functional observatory, put to more purposes than were even imagined in 1842. It became distinguished in several sciences: geomagnetism, me- teorology, solar astronomy, and standardization—the latter term being used in this book to refer to testing scientific instruments and develop- ing prototypes of instruments to be used elsewhere, as well as establish- ing and refining constants and standards of measurement. Many of the major figures in the physical sciences of the nineteenth century were in some way involved with Kew Observatory. For the first twenty months of the twentieth century, Kew was the site of the National Physical Labora- 3 © 2018 University of Pittsburgh Press. -

The Mystery and Majesty

The mystery and majesty Nearly 40 years after THE SPACE AGE BLASTED off when the Soviet Union launched the Voyager 2 visited Uranus world’s first artificial satellite in 1957. Since then, humanity has explored our cosmic and Neptune, scientists are backyard with vigor — and yet two planets have fallen to the planetary probe wayside. eager for new expeditions. In the 63 years since Sputnik, humanity has only visited Neptune and Uranus once BY JOEL DAVIS — when Voyager 2 flew past Uranus in January 1986 and Neptune in August 1989 40 ASTRONOMY • DECEMBER 2020 of the ICE GIANTS — and even that wasn’t entirely pre- interstellar mission, more than a dozen pro- In 1781, Uranus became the first planet planned. The unmitigated success of posals have been offered for return missions ever discovered using a telescope. Nearly 200 years later, Voyager 2 Voyager 1 and 2 on their original mission to one or both ice giants. So far, none have became the first spacecraft to visit to explore Jupiter and Saturn earned the made it past the proposal stage due to lack Uranus and Neptune, in 1986 and 1989 respectively. NASA/JPL twin spacecrafts further missions in our of substantial scientific interest. Effectively, solar system and beyond, with Neptune and the planetary research community has been Uranus acting as the last stops on a Grand giving the ice giants the cold shoulder. Tour of the outer solar system. But recently, exoplanet data began In the 31 years since Voyager 2 left the revealing the abundance of icy exoplanets Neptune system in 1989 and began its in our galaxy “and new questions about WWW.ASTRONOMY.COM 41 With a rotation axis tilted more than 90 degrees compared to its orbital plane, Neptune likewise has a highly tilted rotation axis and tilted magnetic axis. -

The Charles Knight-Joseph Hooker Correspondence

A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 David J. Galloway Hon. Research Associate Landcare Research, and Te Papa Tongarewa [email protected] Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J December 2013 Published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand Inc, 2013 Information on the Society and its publications is given at www.gsnz.org.nz © Copyright David J. Galloway, 2013 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J ISBN 978-1-877480-36-2 ISSN 2230-4495 (Online) ISSN 2230-4487 (Print) This document is available as a PDF file that can be downloaded from the Geoscience Society website at: http://www.gsnz.org.nz/information/misc-series-i-49.html Bibliographic Reference Galloway D.J. 2013: A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J. 88 pages. A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 Contents Introduction 3 Charles Knight correspondence at Kew 5 Acknowledgements 6 Summaries of the letters 7 Transcriptions of the letters from Charles Knight 15 Footnotes 70 References 77 Figure 1: Dr Charles Knight FLS, FRCS 2 Figure 2: Group photograph including Charles Knight 2 Figure 3: Page of letter from Knight to Hooker 14 Table 1: Comparative chronology of Charles Knight, W.J. Hooker and J.D. Hooker 86 1 Figure 1: Dr Charles Knight FLS, FRCS Alexander Turnbull Library,Wellington, New Zealand ¼-015414 Figure 2: Group taken in Walter Mantell‟s garden about 1865 showing Charles Knight (left), John Buchanan and James Hector (right) and Walter Mantell and his young son, Walter Godfrey Mantell (seated on grass). -

Astbury (Arthur Kenelm)

ASTBURY (ARTHUR KENELM). The black fens. 8 0 Cambridge, 1958. .91(4259) Ast. ASTBURY (JOHN). Diss. ... inaug. de morbis cutaneis. 8 0 Edin. , 1781. Att. 77.7.7/16. --- Another copy. Att. 77.7.8/16. ASTBURY (NORMAN FREDERICK). Introduction to electrical applied physics. 80 Lond. , 1956. Engin. Lib. ASTBURY (WILLIAM THOMAS). Fundamentals of fibre structure. With an introd. by Sir W. Bragg. 80 Lond.. 1933. C. M. L. --- Textile fibres under the X-rays. 80 Birmingham pr., n. d. 5397:. 6335 Ast. [ASTELL (MARY). ] An essay in defence of the female sex. In which are inserted the characters of a pedant, a squire, a beau, a vertuoso, a poetaster, a city-critick, &c. In a letter to a lady. Written by a lady. 2nd ed. 120 Lond. , 1696. GGE . a—.4. E-B. 39e Asf ADDITIONS 1 AST B URY (RAYMOND) . --- ed. Libraries and the book trade; papers delivered at a symposium held at Liverpool School of Librarian- ship, May 1967 ... Lond. , 1968. .6555:.02 Ast. --- ed. The writer in the market place. See WRITER (The) in the market place. ASTELL (MARY) continued]. --- A fair way with the Dissenters and their patrons. Not writ by M. L ----- y, or any other furious Jacobite . but by a very moderate person and dutiful subject to the Queen [i.e. M.A.]. Lond., 1704. *A.7.15 4- --- An impartial enquiry into the causes of rebellion and civil war in this kingdom in an examination of Dr. Kennett's sermon, Jan. 31, 1703/4, and indication of the royal martyr. LAnon.1 Lond., 1704. -

The Comparative Exploration of the Ice Giant Planets with Twin Spacecraft

The Comparative Exploration of the Ice Giant Planets with Twin Spacecraft The Comparative Exploration of the Ice Giant Planets with Twin Spacecraft: Unveiling the History of our Solar System Diego Turrini1*, Romolo Politi1, Roberto Peron1, Davide Grassi1, Christina Plainaki1, Mauro Barbieri2, David M. Lucchesi1, Gianfranco Magni1, Francesca Altieri1, Valeria Cottini3, Nicolas Gorius4, Patrick Gaulme5,6, François-Xavier Schmider7, Alberto Adriani1, Giuseppe Piccioni1 1 Institute for Space Astrophysics and Planetology INAF-IAPS, Italy. 2 Center of Studies and Activities for Space CISAS, University of Padova, Italy. 3 University of Maryland, USA. 4 Catholic University of America, USA 5 Department of Astronomy, New Mexico State University, P.O. Box 30001, MSC 4500, Las Cruces, NM 88003-8001, USA 6 Apache Point Observatory, 2001 Apache Point Road, P.O. Box 59, Sunspot, NM 88349, USA 7 Laboratoire Lagrange, Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur, France Abstract In the course of the selection of the scientific themes for the second and third L-class missions of the Cosmic Vision 2015-2025 program of the European Space Agency, the exploration of the ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune was defined “a timely milestone, fully appropriate for an L class mission”. Among the proposed scientific themes, we presented the scientific case of exploring both planets and their satellites in the framework of a single L-class mission and proposed a mission scenario that could allow to achieve this result. In this work we present an updated and more complete discussion of the scientific rationale and of the mission concept for a comparative exploration of the ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune and of their satellite systems with twin spacecraft. -

Sir George Biddell Airy (1801 – 1892)

Sir George Biddell Airy (1801 – 1892) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Biddell_Airy Sir George Biddell Airy PRS KCB was an English mathematician and astronomer, Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881. His many achievements include work on planetary orbits, measuring the mean density of the Earth, a method of solution of two-dimensional problems in solid mechanics and, in his role as Astronomer Royal, establishing Greenwich as the location of the prime meridian. His reputation has been tarnished by allegations that, through his inaction, Britain lost the opportunity of priority in the discovery of Neptune. Biography: Airy was born at Alnwick, one of a long line of Airys who traced their descent back to a family of the same name residing at Kentmere, in Westmorland, in the 14th century. The branch to which he belonged, having suffered in the English Civil War, moved to Lincolnshire and became farmers. Airy was educated first at elementary schools in Hereford, and afterwards at Colchester Royal Grammar School. An introverted child, Airy gained popularity with his schoolmates through his great skill in the construction of peashooters. From the age of 13, Airy stayed frequently with his uncle, Arthur Biddell at Playford, Suffolk. Biddell introduced Airy to his friend Thomas Clarkson, the slave trade abolitionist who lived at Playford Hall. Clarkson had an MA in mathematics from Cambridge, and examined Airy in classics and then subsequently arranged for him to be examined by a Fellow from Trinity College, Cambridge on his knowledge of mathematics. As a result he entered Trinity in 1819, as a sizar, meaning that he paid a reduced fee but essentially worked as a servant to make good the fee reduction. -

Neptune: from Grand Discovery to a World Revealed Essays on the 200Th Anniversary of the Birth of John Couch Adams

springer.com Physics : Astronomy, Observations and Techniques Sheehan, W., Bell, T.E., Kennett, C., Smith, R. (Eds.) Neptune: From Grand Discovery to a World Revealed Essays on the 200th Anniversary of the Birth of John Couch Adams A major reassessment of the discovery of Neptune from a pan-European perspective Written by a distinguished team of extensively published researchers Provides new analysis and theoretical insights into the original discovery of Neptune Springer The 1846 discovery of Neptune is one of the most remarkable stories in the history of science and astronomy. John Couch Adams and U.J. Le Verrier both investigated anomalies in the 1st ed. 2021, XXXI, 403 p. 1st motion of Uranus and independently predicted the existence and location of this new planet. 130 illus., 71 illus. in color. edition However, interpretations of the events surrounding this discovery have long been mired in controversy. Who first predicted the new planet? Was the discovery just a lucky fluke? The ensuing storm engaged astronomers across Europe and the United States. Written by an Printed book international group of authors, this pathbreaking volume explores in unprecedented depth the Hardcover contentious history of Neptune’s discovery, drawing on newly discovered documents and re- examining the historical record. In so doing, we gain new understanding of the actions of key Printed book individuals and sharper insights into the pressures acting on them. The discovery of Neptune Hardcover was a captivating mathematical moment and was widely regarded at the time as the greatest ISBN 978-3-030-54217-7 triumph of Newton’s theory of universal gravitation. -

John Couch Adams: Mathematical Astronomer, College Friend Of

John Couch Adams: mathematical astronomer, rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org college friend of George Gabriel Stokes and promotor Research of women in astronomy Davor Krajnovic´1 Article submitted to journal 1Leibniz-Institut für Astrophysik Potsdam (AIP), An der Sternwarte 16, D-14482 Potsdam, Germany Subject Areas: xxxxx, xxxxx, xxxx John Couch Adams predicted the location of Neptune in the sky, calculated the expectation of the change in Keywords: the mean motion of the Moon due to the Earth’s pull, xxxx, xxxx, xxxx and determined the origin and the orbit of the Leonids meteor shower which had puzzled astronomers for almost a thousand years. With his achievements Author for correspondence: Adams can be compared with his good friend George Davor Krajnovic´ Stokes. Not only were they born in the same year, e-mail: [email protected] but were also both senior wranglers, received the Smith’s Prizes and Copley medals, lived, thought and researched at Pembroke College, and shared an appreciation of Newton. On the other hand, Adams’ prediction of Neptune’s location had absolutely no influence on its discovery in Berlin. His lunar theory did not offer a physical explanation for the Moon’s motion. The origin of the Leonids was explained by others before him. Adams refused a knighthood and an appointment as Astronomer Royal. He was reluctant and slow to publish, but loved to derive the values of logarithms to 263 decimal places. The maths and calculations at which he so excelled mark one of the high points of celestial mechanics, but are rarely taught nowadays in undergraduate courses. -

Back Matter (PDF)

[ 387 ] INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS, S e r ie s A, V ol. 194. A. Alloys of gold and aluminium (Heycock and Neville), 201. B. Bakerian Lecture (Tilden), 233. C. Chappuis (P.). See Habkeb and Chappuis. Children, association of defects in (Yule), 257. Cole (E. S.). See W obthinoton and Cole. Combinatorial analysis (MacMahon), 361. Conductivity of dilute solutions (W hetham), 321. E. Earthquake motion, propagation to great distances (Oldham), 135. G. Gold-aluminium alloys—melting-point curve (Heycock and Neville), 201. Gbindley (John H.). An Experimental Investigation of the Tliermo-dynamical Properties of Superheated Steam.—On the Cooling of Saturated Steam by Free Expansion, 1. H. Habkeb (J. A.) and Chapptjis (P.). A Comparison of Platinum and Gas Thermometers, including a Determination of the Boiling-point of Sulphur on the Nitrogen Scale, 37. Heycock (C. T.) and Neville (F. H.). Gold-aluminium alloys, 201. VOL. CXCIV.---- A 261. 3 D 2 388 INDEX. T. Impact with a liquid surface (W orthington and Cole), 175. Ionization of solutions at freezing point (W hetham), 321. L. Latin square problem (MacMahon), 361. M. MacMahon (P. A.). Combinatorial Analysis.—The Foundations of a New Theory, 361. Metals, specific heats of—relation to atomic weights (Tilden), 233. N. N eville (F. H.). See H eycock and N eville. O. Oldham (R. D.) On the Propagation of Earthquake Motion to Great Distances, 135. P. Perry (John). Appendix to Prof. Tilden’s Bakerian Lecture—Thermo-dynamics of a Solid, 250. R. Resistance coils—standardization o f; manganin as material for (Harker and Chappuis), 37. S. -

A European Perspective on Uranus Mission Architectures

A European perspective on Uranus mission architectures Chris Arridge1,2 1. Mullard Space Science Laboratory, UCL, UK. 2. The Centre for Planetary Sciences at UCL/Birkbeck, UK. Twitter: @chrisarridge Ice Giants Workshop – JHU Applied Physics Laboratory, MD, USA – 30 July 2014 2/32 Overview of the Cosmic Vision • Originated with Horizon and Horizon+ programmes. – Missions born from that programme include Mars Express, Venus Express, ROSETTA, HERSCHEL, Huygens, HST. • Cosmic Vision driven by scientific themes: 1. What are the conditions for planetary formation and the emergence of life? 2. How does the Solar System work? 3. What are the physical fundamental laws of the Universe? 4. How did the Universe originate and what is it made of? • Part of ESA’s mandatory programme – contributions from member states weighted by GDP, • Operate according to a set of guidelines that broadly-speaking demand a programmatic balance (between scientific domains) and due return. 3/32 Overview of the Cosmic Vision • Originated with Horizon and Horizon+ programmes. – Missions born from that programme include Mars Express, Venus Express, ROSETTA, HERSCHEL, Huygens, HST. • Cosmic Vision driven by scientific themes: 1. What are the conditions for planetary formation and the emergence of life? 2. How does the Solar System work? 3. What are the physical fundamental laws of the Universe? 4. How did the Universe originate and what is it made of? • Part of ESA’s mandatory programme – contributions from member states weighted by GDP, • Operate according to a set of guidelines that broadly-speaking demand a programmatic balance (between scientific domains) and due return. 4/32 Mission classes • Medium “M”-class: 500 M€ - example Solar Orbiter. -

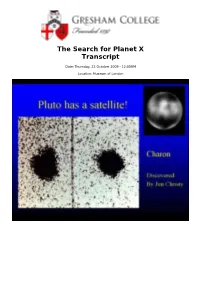

The Search for Planet X Transcript

The Search for Planet X Transcript Date: Thursday, 22 October 2009 - 12:00AM Location: Museum of London The Search for Planet X Professor Ian Morison The Hunt for Planet X This is a story that spanned over 200 years: from the discovery that Uranus was not following its predicted orbit and was thus presumably being perturbed by another, as yet undiscovered planet, Neptune, followed by the search for what Percival Lowell called "Planet X" that would lie beyond Neptune (where X means unknown), and finally the search for a tenth planet beyond Pluto (where X means ten as well). As we shall see, the search for a tenth planet effectively ended in August 2006 when Pluto was demoted from its status as a planet and the number of planets in the solar system was reduced to eight. Uranus Uranus was the first planet to have been discovered in modern times and though, at magnitude ~5.5, it is just visible to the unaided eye without a telescope it would have been impossible to show that it was a planet rather than a star, save for its slow motion across the heavens. Even when telescopes had come into use, their relatively poor optics meant that it was charted as a star many times before it was recognised as a planet by William Herschel in 1781. William Herschel had come to England from Hanover in Germany where his father, Isaac, was an oboist in the band of the Hanoverian Foot Guards. As well as giving his third child, Freidrich Wilhelm Herschel, a thorough grounding in music he gave him an interest in the heavens.