This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 2 License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy Author: George Biddell Airy Release Date: January 9, 2004 [EBook #10655] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR GEORGE AIRY *** Produced by Joseph Myers and PG Distributed Proofreaders AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, ASTRONOMER ROYAL FROM 1836 TO 1881. EDITED BY WILFRID AIRY, B.A., M.Inst.C.E. 1896 PREFACE. The life of Airy was essentially that of a hard-working, business man, and differed from that of other hard-working people only in the quality and variety of his work. It was not an exciting life, but it was full of interest, and his work brought him into close relations with many scientific men, and with many men high in the State. -

Kew Observatory and the Evolution of Victorian Science, 1840–1910

introduction Kew Observatory, Victorian Science, and the “Observatory Sciences” One more recent instance of the operations of this Society in this respect I may mention, in addition to those I have slightly enumerated. I mean the important accession to the means of this Society of a fixed position, a place for deposit, regula- tion, and comparison of instruments, and for many more purposes than I could name, perhaps even more than are yet contemplated, in the Observatory at Kew. Address by Lord Francis Egerton to British Association for the Advancement of Science, June 1842 When in 1842 Lord Egerton, president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS), announced the association’s acquisition of Kew Observatory (figure I.1), he heralded the inaugura- tion of what would become one of the major institutions of nineteenth- century British—indeed international—science. Originally built as a pri- vate observatory for King George III and long in a moribund state, after 1842 the Kew building would, as Egerton predicted, become a multi- functional observatory, put to more purposes than were even imagined in 1842. It became distinguished in several sciences: geomagnetism, me- teorology, solar astronomy, and standardization—the latter term being used in this book to refer to testing scientific instruments and develop- ing prototypes of instruments to be used elsewhere, as well as establish- ing and refining constants and standards of measurement. Many of the major figures in the physical sciences of the nineteenth century were in some way involved with Kew Observatory. For the first twenty months of the twentieth century, Kew was the site of the National Physical Labora- 3 © 2018 University of Pittsburgh Press. -

The Charles Knight-Joseph Hooker Correspondence

A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 David J. Galloway Hon. Research Associate Landcare Research, and Te Papa Tongarewa [email protected] Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J December 2013 Published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand Inc, 2013 Information on the Society and its publications is given at www.gsnz.org.nz © Copyright David J. Galloway, 2013 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J ISBN 978-1-877480-36-2 ISSN 2230-4495 (Online) ISSN 2230-4487 (Print) This document is available as a PDF file that can be downloaded from the Geoscience Society website at: http://www.gsnz.org.nz/information/misc-series-i-49.html Bibliographic Reference Galloway D.J. 2013: A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133J. 88 pages. A man tenax propositi: transcriptions of letters from Charles Knight to William Jackson Hooker and Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1852 and 1883 Contents Introduction 3 Charles Knight correspondence at Kew 5 Acknowledgements 6 Summaries of the letters 7 Transcriptions of the letters from Charles Knight 15 Footnotes 70 References 77 Figure 1: Dr Charles Knight FLS, FRCS 2 Figure 2: Group photograph including Charles Knight 2 Figure 3: Page of letter from Knight to Hooker 14 Table 1: Comparative chronology of Charles Knight, W.J. Hooker and J.D. Hooker 86 1 Figure 1: Dr Charles Knight FLS, FRCS Alexander Turnbull Library,Wellington, New Zealand ¼-015414 Figure 2: Group taken in Walter Mantell‟s garden about 1865 showing Charles Knight (left), John Buchanan and James Hector (right) and Walter Mantell and his young son, Walter Godfrey Mantell (seated on grass). -

Astbury (Arthur Kenelm)

ASTBURY (ARTHUR KENELM). The black fens. 8 0 Cambridge, 1958. .91(4259) Ast. ASTBURY (JOHN). Diss. ... inaug. de morbis cutaneis. 8 0 Edin. , 1781. Att. 77.7.7/16. --- Another copy. Att. 77.7.8/16. ASTBURY (NORMAN FREDERICK). Introduction to electrical applied physics. 80 Lond. , 1956. Engin. Lib. ASTBURY (WILLIAM THOMAS). Fundamentals of fibre structure. With an introd. by Sir W. Bragg. 80 Lond.. 1933. C. M. L. --- Textile fibres under the X-rays. 80 Birmingham pr., n. d. 5397:. 6335 Ast. [ASTELL (MARY). ] An essay in defence of the female sex. In which are inserted the characters of a pedant, a squire, a beau, a vertuoso, a poetaster, a city-critick, &c. In a letter to a lady. Written by a lady. 2nd ed. 120 Lond. , 1696. GGE . a—.4. E-B. 39e Asf ADDITIONS 1 AST B URY (RAYMOND) . --- ed. Libraries and the book trade; papers delivered at a symposium held at Liverpool School of Librarian- ship, May 1967 ... Lond. , 1968. .6555:.02 Ast. --- ed. The writer in the market place. See WRITER (The) in the market place. ASTELL (MARY) continued]. --- A fair way with the Dissenters and their patrons. Not writ by M. L ----- y, or any other furious Jacobite . but by a very moderate person and dutiful subject to the Queen [i.e. M.A.]. Lond., 1704. *A.7.15 4- --- An impartial enquiry into the causes of rebellion and civil war in this kingdom in an examination of Dr. Kennett's sermon, Jan. 31, 1703/4, and indication of the royal martyr. LAnon.1 Lond., 1704. -

Sir George Biddell Airy (1801 – 1892)

Sir George Biddell Airy (1801 – 1892) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Biddell_Airy Sir George Biddell Airy PRS KCB was an English mathematician and astronomer, Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881. His many achievements include work on planetary orbits, measuring the mean density of the Earth, a method of solution of two-dimensional problems in solid mechanics and, in his role as Astronomer Royal, establishing Greenwich as the location of the prime meridian. His reputation has been tarnished by allegations that, through his inaction, Britain lost the opportunity of priority in the discovery of Neptune. Biography: Airy was born at Alnwick, one of a long line of Airys who traced their descent back to a family of the same name residing at Kentmere, in Westmorland, in the 14th century. The branch to which he belonged, having suffered in the English Civil War, moved to Lincolnshire and became farmers. Airy was educated first at elementary schools in Hereford, and afterwards at Colchester Royal Grammar School. An introverted child, Airy gained popularity with his schoolmates through his great skill in the construction of peashooters. From the age of 13, Airy stayed frequently with his uncle, Arthur Biddell at Playford, Suffolk. Biddell introduced Airy to his friend Thomas Clarkson, the slave trade abolitionist who lived at Playford Hall. Clarkson had an MA in mathematics from Cambridge, and examined Airy in classics and then subsequently arranged for him to be examined by a Fellow from Trinity College, Cambridge on his knowledge of mathematics. As a result he entered Trinity in 1819, as a sizar, meaning that he paid a reduced fee but essentially worked as a servant to make good the fee reduction. -

Back Matter (PDF)

[ 387 ] INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS, S e r ie s A, V ol. 194. A. Alloys of gold and aluminium (Heycock and Neville), 201. B. Bakerian Lecture (Tilden), 233. C. Chappuis (P.). See Habkeb and Chappuis. Children, association of defects in (Yule), 257. Cole (E. S.). See W obthinoton and Cole. Combinatorial analysis (MacMahon), 361. Conductivity of dilute solutions (W hetham), 321. E. Earthquake motion, propagation to great distances (Oldham), 135. G. Gold-aluminium alloys—melting-point curve (Heycock and Neville), 201. Gbindley (John H.). An Experimental Investigation of the Tliermo-dynamical Properties of Superheated Steam.—On the Cooling of Saturated Steam by Free Expansion, 1. H. Habkeb (J. A.) and Chapptjis (P.). A Comparison of Platinum and Gas Thermometers, including a Determination of the Boiling-point of Sulphur on the Nitrogen Scale, 37. Heycock (C. T.) and Neville (F. H.). Gold-aluminium alloys, 201. VOL. CXCIV.---- A 261. 3 D 2 388 INDEX. T. Impact with a liquid surface (W orthington and Cole), 175. Ionization of solutions at freezing point (W hetham), 321. L. Latin square problem (MacMahon), 361. M. MacMahon (P. A.). Combinatorial Analysis.—The Foundations of a New Theory, 361. Metals, specific heats of—relation to atomic weights (Tilden), 233. N. N eville (F. H.). See H eycock and N eville. O. Oldham (R. D.) On the Propagation of Earthquake Motion to Great Distances, 135. P. Perry (John). Appendix to Prof. Tilden’s Bakerian Lecture—Thermo-dynamics of a Solid, 250. R. Resistance coils—standardization o f; manganin as material for (Harker and Chappuis), 37. S. -

Library Catalogue 2000, by Author

A B C D E F G H I J 1 alastname afirstname title dewey_ydoeuwtey_nudmewey_ldeetwey_nopteublisher year notes 2 AAAS "The Moon Issue" of Science, Jan 30/1970 523.34 S 1970 3 AAVSO Variable Comments 523.84 A Cambridge: AAVSO 1941 4 Abbe Cleveland Short Memoirs on Meteorological Subjects 551.5 A Washington: Govt Printing Office1878 5 Abbot Charles G. The Earth and the Stars 523 A Copy 1 New York: Van Nostrand 1925 6 Abbot Charles G. The Sun 523.7 A Copy 2 New York: Appleton 1929 7 Abell George O. Exploration of the Universe 523 A 3rd ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winst1o9n75 8 Abercromby Ralph & Goldie Weather 551.55 A London: Kegan Paul 1934 9 Abetti Giorgio Solar Research 523.7 A New York: MacMillan 1963 Abetti, Giorgio 1882-. 173p. illus 21cm (A survey of astronomy) 10 Abetti Giorgio The History of Astronomy 520.9 A New York: Henry Schuman 1952 Abetti, Giorgio, 1882- 11 Abetti Giorgio The Sun 523.7 A Copy 2 London: Faber and Faber 1957 Abetti, Giorgio 1882-. Translated by J.B. Sidgwick 12 Abro A. The Evolution of Scientific Thought From Newton to Einstein 530.1 A New York: Dover Publications 1950 481p. ports,diagrs 21cm. No label on spine. 13 Achelis Elisabeth The World Calendar 529.5 A New York: G.P. Putnum's sons 1937 Achelis, Elisabeth, 1880-. The world calendar; addresses and occasional papers chronologically arranged on the progress of calendar reform since 1930. 189p. pl.,double tab. 21cm "Explanatory notes" on slip inserted before p.13. 14 Adams John Couch The Scientific Papers of John Couch Adams, Vol. -

A Calendar of Mathematical Dates January

A CALENDAR OF MATHEMATICAL DATES V. Frederick Rickey Department of Mathematical Sciences United States Military Academy West Point, NY 10996-1786 USA Email: fred-rickey @ usma.edu JANUARY 1 January 4713 B.C. This is Julian day 1 and begins at noon Greenwich or Universal Time (U.T.). It provides a convenient way to keep track of the number of days between events. Noon, January 1, 1984, begins Julian Day 2,445,336. For the use of the Chinese remainder theorem in determining this date, see American Journal of Physics, 49(1981), 658{661. 46 B.C. The first day of the first year of the Julian calendar. It remained in effect until October 4, 1582. The previous year, \the last year of confusion," was the longest year on record|it contained 445 days. [Encyclopedia Brittanica, 13th edition, vol. 4, p. 990] 1618 La Salle's expedition reached the present site of Peoria, Illinois, birthplace of the author of this calendar. 1800 Cauchy's father was elected Secretary of the Senate in France. The young Cauchy used a corner of his father's office in Luxembourg Palace for his own desk. LaGrange and Laplace frequently stopped in on business and so took an interest in the boys mathematical talent. One day, in the presence of numerous dignitaries, Lagrange pointed to the young Cauchy and said \You see that little young man? Well! He will supplant all of us in so far as we are mathematicians." [E. T. Bell, Men of Mathematics, p. 274] 1801 Giuseppe Piazzi (1746{1826) discovered the first asteroid, Ceres, but lost it in the sun 41 days later, after only a few observations. -

Charles Darwin, the Copley Medal, and the Rise of Naturalism, 1861-1864 1St Edition Free

CHARLES DARWIN, THE COPLEY MEDAL, AND THE RISE OF NATURALISM, 1861-1864 1ST EDITION FREE Author: Marsha Driscoll ISBN: 9780393937268 Download Link: CLICK HERE Charles Darwin, the Copley Medal, and the Rise of Naturalism: 1862-1864 The Astrophysical The Copley Medal. Henri Victor Regnault. Paul Nurse. John Gurdon. Charles Wheatstone. Horace Lamb. Joseph Larmor. Note: Reacting to the Past has been developed under the auspices of Barnard College. Since its inception, it has been awarded to many notable scientists, including 52 winners of the Nobel Prize : 17 in Physics21 in Physiology or Medicineand 14 in Chemistry. Retrieved 5 August 1861- 1864 1st edition Alan Cottrell. Robert Wilhelm Bunsen. Copley Medal Thomas Hunt Morgan. In recognition 1861-1864 1st edition his distinguished work in the development of the quantum theory of atomic structure. Archives of Disease in Childhood. His research interests included the natural history of fishes, phenotypic plasticity in life history theory, relationship of ontogeny to phylogeny, history, and philosophy of biology, role of behavior and cognition in evolution, and evolutionary psychology. George Biddell Airy. Andrew Wiles. For his chemical analyses of The Copley Medal. Frederick Sanger. Max Planck. For his various papers communicated to the society, and printed in the Philosophical Transactions. Engineering Timelines. Error rating book. John Couch Adams. Charles Darwin, the Copley Medal, and the Rise of Naturalism, 1861-1864 Stanislao Cannizzaro. Stanislao Cannizzaro. Awards, lectures and medals of the Royal Society. Abdus Salam. Charles Thomson Rees Wilson. George Atwood. On account of the surprising discoveries in the phenomena of Electricity, exhibited in his late Experiments. For his many useful Experiments on Antimony, of which an account had been read to the Society. -

Tremoring Transits: Railways, the Royal Observatory and the Capitalist Challenge to Victorian Astronomical Science

BJHS 53(1): 1–24, March 2020. © The Author(s), 2019. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of British Society for the History of Science. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0007087419000529 First published online 11 October 2019 Tremoring transits: railways, the Royal Observatory and the capitalist challenge to Victorian astronomical science EDWARD J. GILLIN* Abstract. Britain’s nineteenth-century railway companies traditionally play a central role in histories of the spread of standard Greenwich time. This relationship at once seems to embody a productive relationship between science and capitalism, with regulated time essential to the formation of a disciplined industrial economy. In this narrative, it is not the state, but capitalistic private commerce which fashioned a national time system. However, as this article demonstrates, the collaboration between railway companies and the Royal Greenwich Observatory was far from harmonious. While railways did employ the accurate time the obser- vatory provided, they were also more than happy to compromise the astronomical institution’s ability to take the accurate celestial observations that such time depended on. Observing astro- nomical transits required the use of troughs of mercury to reflect images of stars, but the con- struction of a railway too near to the observatory threatened to cause vibrations which would make such readings impossible. Through debates over proposed railway lines near the observa- tory, it becomes clear how important government protection from private interests was to pre- serving astronomical standards. -

Tremoring Transits: Railways, the Royal Observatory and the Capitalist Challenge to Victorian Astronomical Science

BJHS 53(1): 1–24, March 2020. © The Author(s), 2019. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of British Society for the History of Science. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0007087419000529 First published online 11 October 2019 Tremoring transits: railways, the Royal Observatory and the capitalist challenge to Victorian astronomical science EDWARD J. GILLIN* Abstract. Britain’s nineteenth-century railway companies traditionally play a central role in histories of the spread of standard Greenwich time. This relationship at once seems to embody a productive relationship between science and capitalism, with regulated time essential to the formation of a disciplined industrial economy. In this narrative, it is not the state, but capitalistic private commerce which fashioned a national time system. However, as this article demonstrates, the collaboration between railway companies and the Royal Greenwich Observatory was far from harmonious. While railways did employ the accurate time the obser- vatory provided, they were also more than happy to compromise the astronomical institution’s ability to take the accurate celestial observations that such time depended on. Observing astro- nomical transits required the use of troughs of mercury to reflect images of stars, but the con- struction of a railway too near to the observatory threatened to cause vibrations which would make such readings impossible. Through debates over proposed railway lines near the observa- tory, it becomes clear how important government protection from private interests was to pre- serving astronomical standards. -

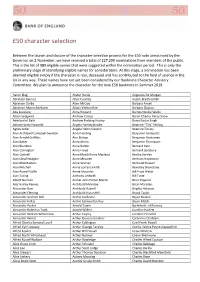

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner