Mellon-Hawai'i Doctoral and Postdoctoral Fellows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conversing with Pelehonuamea: a Workshop Combining 1,000+ Years of Traditional Hawaiian Knowledge with 200 Years of Scientific Thought on Kīlauea Volcanism

Conversing with Pelehonuamea: A Workshop Combining 1,000+ Years of Traditional Hawaiian Knowledge with 200 Years of Scientific Thought on Kīlauea Volcanism Open-File Report 2017–1043 Version 1.1, June 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Conversing with Pelehonuamea: A Workshop Combining 1,000+ Years of Traditional Hawaiian Knowledge with 200 Years of Scientific Thought on Kīlauea Volcanism Compiled and Edited by James P. Kauahikaua and Janet L. Babb Open-File Report 2017–1043 Version 1.1, June 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William H. Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 First release: 2017 Revised: June 2017 (ver. 1.1) For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod/. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Kauahikaua, J.P., and Babb, J.L., comps. and eds., Conversing with Pelehonuamea—A workshop combining 1,000+ years of traditional Hawaiian knowledge with 200 years of scientific thought on Kīlauea volcanism (ver. -

The Arabian Nights in Nineteenth-Century Hawaiian Newspapers

TRANSLATION IN THE CULTURE WAR FOR HAWAII The Arabian Nights in Nineteenth-Century Hawaiian Newspapers ALYSSA HUGHES THIS ARTICLE DISCUSSES THE MOTIVATIONS BEHIND THE TRANSLATIONS OF THE ARABIAN NIGHTS IN TWO COMPETING N I N ET E E N T H-C E N T U R Y H A W A I I A N - LA N G U AG E NEWSPAPERS: KA HOKU PAKIPIKA AND KA NUPEPA KUOKOA. TRANSLATIONS OF THE ARABIAN NIGHTS SERVE AS AN EPICENTER OF CULTURAL CONFLICT IN THE WAR FOR SOCIETAL AND POLITICAL DOMINANCE OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS ON THE EVE OF THEIR ANNEXATION TO THE UNITED STATES. FURTHERMORE, THE ROLE OF TRANSLA- TION ITSELF IN THE FORMATION OF CULTURAL IDENTITIES IS DISCUSSED, FOCUSING ON THE ROLE OF THE TRANSLATIONS OF THE ARABIAN NIGHTS IN THE WAR FOR CULTURAL HEGEMONY IN N I N ET E E N T H - C E N T U R Y HAWAII. INTRODUCTION: SHAHRAZAD'S TALE various translations of the Arabic tales in Hawaiian-lan- ARRIVES IN THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS guage publications are more than simply another example of The Arabian Nights' dual nature—the tales' ability to On April 24, 1862, the Hawaiian-language newspaper Ka exist in oral, printed and illustrated forms in societies so Hoku Pakipika published the story of Samesala Naeha, far-removed from that of their inception.111 In the case of "Moolelo no Samesala Naeha! O ka Moolelo keia o ka Mea The Arabian Nights in Hawaii, the tales act as a reflection of nana i haku i na Kaao Arabia" ("The Arabian Tale of colonial Hawaii mediated through language.lv Samesala Naeha"), a translation of the frame tale of The Arabian Nights. -

Joyce Pualani Warren

DOI 10.17953/aicrj.43.2.warren Reading Bodies, Writing Blackness: Anti-/Blackness and Nineteenth- Century Kanaka Maoli Literary Nationalism Joyce Pualani Warren June 5, 1850, journal entry written by fifteen-year-old Hawaiian Prince Alexander A Liholiho, the future King Kamehameha IV, details his experience of anti-Black discrimination on a train in Washington, DC. The conductor “told [him] to get out of the carriage rather unceremoniously,” because of his skin color, “saying that [he] was in the wrong carriage.”1 For Alexander Liholiho, a law school student as well as the future monarch, this diplomatic tour of the United States and Europe was an opportunity to interact with foreign heads of state. Although the conductor deferred to the prince after someone whispered into the official’s ear at a critical moment in the argument, Alexander Liholiho surmised in his entry, “he had taken me for somebodys servant [sic], just because I had a darker skin than he had. Confounded fool.”2 During a soiree at the White House only days earlier President Zachary Taylor and Vice President Millard Fillmore had treated him as an equal; now a train conductor cruelly abused him as a “servant” in need of correction. Perhaps ironically, the young prince had found the president’s “plain citizens dress” [sic] lacking in comparison to his own “belted & cocked” attire, yet none of the outward markers of his royalty registered with the conductor.3 Instead, the conductor misreads Alexander Liholiho’s body based on his racist assumption that a Black body, or a body approximating one, could occupy no other narrative than the one inscribed Joyce Pualani Warren is an assistant professor in the Department of English at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. -

(Letters from California, the Foreign Land) Kānaka Hawai'i Agency A

He Mau Palapala Mai Kalipōnia Mai, Ka ʻĀina Malihini (Letters from California, the Foreign Land) Kānaka Hawai’i Agency and Identity in the Eastern Pacific (1820-1900) By April L. Farnham A thesis submitted to Sonoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Committee Members: Dr. Michelle Jolly, Chair Dr. Margaret Purser Dr. Robert Chase Date: December 13, 2019 i Copyright 2019 By April L. Farnham ii Authorization for Reproduction of Master’s Thesis Permission to reproduce this thesis in its entirety must be obtained from me. Date: December 13, 2019 April L. Farnham Signature iii He Mau Palapala Mai Kalipōnia Mai, Ka ʻĀina Malihini (Letters from California, the Foreign Land) Kānaka Hawai’i Agency and Identity in the Eastern Pacific (1820-1900) Thesis by April L. Farnham ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to explore the ways in which working-class Kānaka Hawai’i (Hawaiian) immigrants in the nineteenth century repurposed and repackaged precontact Hawai’i strategies of accommodation and resistance in their migration towards North America and particularly within California. The arrival of European naturalists, American missionaries, and foreign merchants in the Hawaiian Islands is frequently attributed for triggering this diaspora. However, little has been written about why Hawaiian immigrants themselves chose to migrate eastward across the Pacific or their reasons for permanent settlement in California. Like the ali’i on the Islands, Hawaiian commoners in the diaspora exercised agency in their accommodation and resistance to Pacific imperialism and colonialism as well. Blending labor history, religious history, and anthropology, this thesis adopts an interdisciplinary and ethnohistorical approach that utilizes Hawaiian-language newspapers, American missionary letters, and oral histories from California’s indigenous peoples. -

Pepeluali 2018 | Buke 35, Helu 2

Pepeluali 2018 | Buke 35, Helu 2 ‘O Faith Kaihopo¯lanihiwahiwa Hi‘ilei‘ilikeaopumehana De Ramos kekahi moho lanakila ma ‘Aha Aloha ‘O¯lelo 2018. - Ki‘i: Bryson Ho/‘O¯iwi TV THE LIVING WATER OF OHA www.oha.org/kwo $REAMINGOF THEFUTURE Hāloalaunuiakea Early Learning Center is a place where keiki love to go to school. It‘s also a safe place where staff feel good about helping their students to learn and prepare for a bright future. The center is run by Native Hawaiian U‘ilani Corr-Yorkman. U‘ilani wasn‘t always a business owner. She actually taught at DOE for 8 years. A Mālama Loan from OHA helped make her dream of owning her own preschool a reality. The low-interest loan allowed U‘ilani to buy fencing for the property, playground equipment, furniture, books…everything needed to open the doors of her business. U‘ilani and her staff serve the community in ‘Ele‘ele, Kaua‘i, and have become so popular that they have a waiting list. OHA is proud to support Native Hawaiian entrepreneurs in the pursuit of their business dreams. OHA‘s staff provide Native Hawaiian borrowers with personalized support and provide technical assistance to encourage the growth of Native Hawaiian businesses. Experience the OHA Loans difference. Call (808) 594-1924 or visit www.oha.org/ loans to learn how a loan from OHA can help grow your business. -A LAMALOAN CANMAKEYOURDREAMSCOMETRUE (808) 594-1924 www.oha.org/loans follow us: /oha_hawaii | /oha_hawaii | fan us: /officeofhawaiianaffairs | watch us: /OHAHawaii pepeluali 2018 3 ‘o¯lElo A kA lunA ho‘okElE MessAge frOM tHe CeO ‘o¯ lelo haWai‘i empoWers our la¯ hui Aloha mai ka¯kou, tongue to thrive, it should be used in as many spaces as possible, including while seeking justice in a Maui courtroom. -

Indigenous Protocol and Artificial Intelligence Workshops Position Paper 1 Indigenous Protocol and Artificial Intelligence Position Paper

Position Paper Indigenous Protocol and Artifi cial Intelligence Indigenous Protocol and Artifi cial Intelligence Woring Grou 30 January 2020 Honolulu, Hawaiʻi indigenousai.net inoindigenousai.net Indigenous Protocol and Artificial Intelligence Workshops Position Paper 1 Indigenous Protocol and Artificial Intelligence Position Paper Cite this Document Lewis, Jason Edward, ed. 2020. Indigenous Protocol and Artificial Intelligence Position Paper. Honolulu, Hawaiʻi: The Initiative for Indigenous Futures and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR). DOI: 10.11573/spectrum.library.concordia.ca.00986506 Download at https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/986506 Report Authors Indigenous Protocol and Artificial Intelligence Working Group. Copyright © 2020 Individual texts are copyright of their respective authors. Unsigned texts are copyright of the Indigenous Protocol and Artificial Intelligence Working Group. CONTENTS 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................3 Guidelines for 2 Indigenous-centred AI Design v.1 ..............................................20 3 Contexts 3.1. Workshop Description ............................................................................................25 3.2. AI: A New (R)evolution or the New Colonizer for Indigenous Peoples ............34 Dr. Hēmi Whaanga 3.3. The IP AI Workshops as Future Imaginary .........................................................39 Jason Edward Lewis 4 Vignettes 4.1. Gwiizens, the Old Lady and the Octopus -

The Dispossession of Native Hawaiians' Identity, and Their Struggle for Sovereignty

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CSUSB ScholarWorks California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2017 Hawaiian History: The Dispossession of Native Hawaiians' Identity, and Their Struggle for Sovereignty Megan Medeiros CSUSB, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Law Commons, Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Medeiros, Megan, "Hawaiian History: The Dispossession of Native Hawaiians' Identity, and Their Struggle for Sovereignty" (2017). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 557. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/557 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HAWAIIAN HISTORY: THE DISPOSSESSION OF NATIVE HAWAIIANS’ IDENTITY, AND THEIR STRUGGLE FOR SOVEREIGNTY ______________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino _______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences and Globalization ______________________ by Megan Theresa Ualaniha’aha’a Medeiros -

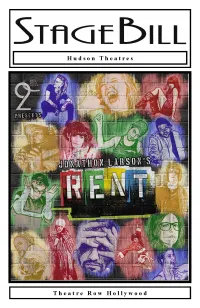

RENT Program

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Remember the first time you were inspired by a performance? The first time that your eyes opened just a little bit wider to try to capture and record everything you were seeing? Maybe it was your first Broadway show, or the first film that really grabbed you. Maybe it was as simple as a third-grade performance. It’s hard to forget that initial sense of wonder and sudden realization that the world might just contain magic . This is the sort of experience the 2Cents Theatre Group is trying to create. Classic performances are hard to define, but easy to spot. Our Goal is to pay homage and respect to the classics, while simultaneously adding our own unique 2 Cents to create a free-standing performance piece that will bemuse, inform, and inspire. 2¢ Theatre Group is in residence at the Hudson Theatre, at 6539 Santa Monica Boulevard. You can catch various talented members of the 2 Cent Crew in our Monthly Cabaret at the Hudson Theatre Café . the second Sunday of each Month. also from 2Cents AT THE HUDSON… TICKETS ON SALE NOW! May 30 - June 30 EACH WEEK FEATURING LIVE PRE-SHOW MUSIC BY: Thurs 5/30 - Stage 11 Sun 6/2 - Anderson William Thurs 6/6 - 30 North SuN 6/9 - Kelli Debbs Thurs 6/13 - TBD Sun 6/16 - Lee Wahlert Thurs 6/20 - TBD Sun 6/23 - TBD Thurs 6/27 - Fire Chief Charlie Sun 6/30 - Chris Duquee Cody Lyman Kristen Boulé & 2Cents Theatre Board of Directors with Michael Abramson at the Hudson Theatres present Book, Music & Lyrics by Jonathan Larson Dedrick Bonner Kate Bowman Amber Bracken Ariel Jean Brooker Brian -

Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6t1nb227 No online items Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: Finding Aid Processed by Brooke M. Black. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2002 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: mssEMR 1-1323 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers Dates (inclusive): 1766-1944 Bulk dates: 1860-1915 Collection Number: mssEMR 1-1323 Creator: Emerson, Nathaniel Bright, 1839-1915. Extent: 1,887 items. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of Hawaiian physician and author Nathaniel Bright Emerson (1839-1915), including a a wide range of material such as research material for his major publications about Hawaiian myths, songs, and history, manuscripts, diaries, notebooks, correspondence, and family papers. The subjects covered in this collection are: Emerson family history; the American Civil War and army hospitals; Hawaiian ethnology and culture; the Hawaiian revolutions of 1893 and 1895; Hawaiian politics; Hawaiian history; Polynesian history; Hawaiian mele; the Hawaiian hula; leprosy and the leper colony on Molokai; and Hawaiian mythology and folklore. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

Notable Hawaiians of the 20Th Century

Notable Hawaiians of the 20th Century Notable Hawaiians • Notable Hawaiians Hawaiians • Notable Hawaiians • Notable Hawaiians When the second issue of ‘Öiwi: A Native newspaper and magazine articles, television Hawaiian Journal was being conceptualized news reports, and an occasional book profile in 1999, it was difficult to ignore the highlighted a few Hawaiians now and then, number of “best of” lists which were being no one had taken account at any length of announced on almost a daily basis. It seemed Hawaiians who were admired by and who as if we couldn’t get enough—What were inspired other Hawaiians. the most important books of the millennium? The one hundred most significant events? We began discussing this idea amongst The best and worst dressed movie stars? ourselves: Whom did we consider noteworthy While sometimes humorous, thought- and important? Whom were we inspired by provoking, and/or controversial, the in our personal, spiritual, and professional categories were also nearly endless. Yet all lives? These conversations were enthusiastic the hoopla was difficult to ignore. After all, and spirited. Yet something was missing. there was one question not being addressed What was it? Oh yes—the voice of the in the general media at both the local and people. We decided that instead of imposing national levels: Who were the most notable our own ideas of who was inspirational and Hawaiians of the 20th century? After all the noteworthy, we would ask the Hawaiian attention given over the years to issues of community: “Who do you, the -

The Kohala Center Leaflet

TKC Leaflet: July/August 2008 Newsletter July/August 2008 Front Page Native Hawaiian Scholars Awarded Mellon Fellowships Photo: Noelani Arista hiking the Palehua Trail in the Makakilo area of O'ahu. "Our halau (hula troupe) goes hiking at least once a month to learn about the different plants, places, and wind and rain names," she says. "From this point on the trail, I could see all of Nanakuli Valley where I live." Five leading Hawaiian scholars have been selected as the first cohort of Mellon-Hawai'i Doctoral and Postdoctoral Fellows. Three postdoctoral fellowships of $50,000 each and two doctoral fellowships of $40,000 each were awarded for the 2008-09 academic year. Fellows were evaluated on the basis of their leadership potential and their demonstrated commitment to the advancement of scholarship on Hawaiian cultural and natural environments, or Hawaiian history, politics, and society. The fellows were selected by a distinguished panel of senior scholars and kupuna (elders) comprised of Robert Lindsey Jr., Kohala Center Board of Directors; Dr. Shawn Kana'iaupuni, Kamehameha Schools; Dr. Dennis Gonsalves, Pacific Basin Agricultural Research Center; Dr. Pualani Kanahele, Edith Kanaka'ole Foundation; and Dr. James Kauahikaua, U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. "The Kamehemeha Schools is delighted to join with The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and The Kohala Center to support the work of gifted Hawaiian scholars. We expect nothing less from them than to assume top leadership posts in their fields, shaping the world and our island home with knowledge from both. Competing for such scholarships takes excellence in knowledge, experience, and character – these scholars have met these standards and will, upon completion, share their insights with the world." - Dee Jay Mailer, CEO of the Kamehameha Schools The following individuals were awarded doctoral fellowships: Noelani Arista, Ph.D. -

He Kalailaina I Ka L1mu Ma Ka La'au Lapa'au: He Ninauele Me Hulu Kupuna Henry Allen Auwae

HE KALAILAINA I KA L1MU MA KA LA'AU LAPA'AU: HE NINAUELE ME HULU KUPUNA HENRY ALLEN AUWAE AN ANALYSIS OF L1MU USED IN HAWAIIAN MEDICINE: AN INTERVIEW WITH ESTEEMED ELDER HENRY ALLEN AUWAE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN BOTANY AUGUST 2004 By Kaleleonalani Napoleon Thesis Committee: Will McClatchey, Chairperson Isabella Abbott Nanette Judd Copyright 2004 By Kaleleonalani Napoleon iii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS IV LIST OF TABLES Vll NA MAHALO IX HAWAIIAN LANGUAGE xl PREFACE xIII INTRODUCTION 1 Ka Wa 'Akahi 1 Oli, Mele, Mo'olelo, and Mo'okn'auhau 3 Limu and The Kumulipo 4 Creation Accounts 7 The Christianization of Hawai'i 10 Hawaiian Spirituality 11 Akua and 'Aumakua 13 Hawaiian Values 15 The Kapu System 16 The Evolution of Food and Medicine 17 Na Kahuna 18 Hawaiian Healing 20 Na La'au 22 La'au Lapa'au 23 Prayer, Ceremony, Medicine, and Limu 23 Na Kahuna La'au Lapa'au 26 The Effects of Foreign Contact 27 Survival of na Kahuna 30 Preserving Ethnobotanical Knowledge 32 Algae, Limu and Seaweeds 36 Limu in the Literature 37 Medicinal Uses of Limu in the Literature 39 Literature Review 44 Shared Cultural Knowledge 45 Papa Auwae Biography 47 Hawaiian Health Care 48 Research Purpose 50 HYPOTHESES AND METHODOLOGy 52 Hypotheses 52 Ethnobotanical Research Methodology 52 Specimen Collections 52 Specimen Identification 53 Voucher Specimens 53 Ethnobotanical Data 54 iv The Interview 54 Informant Selection 55 Establishing