Abomasal Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ruminant Digestion a Closer Look

Ruminant Digestion A Closer Look Goal: To Understand the basics of Ruminant Digestive Systems Objectives: To identify basic structures Associated with Ruminant Digestive Systems. To Understand Prehension, Mastication and Rumination To Understand the Process of Digestion and Absorption Section 1 Overview of Digestive Tract and Anatomy – Review Questions 1. Which of the following terms refers to the part of a structure closest to the belly? a. Anterior b. Posterior c. Ventral d. Dorsal 2. Which of the following structures is considered to be the true stomach in ruminants? a. Rumen b. Reticulum c. Omasum d. Abomasum 1 3. What man-made physical object is placed into the side of live cattle so scientists can access the rumen to study the contents during digestion? a. Appendix b. Rectum c. Cannula d. Laparoscope 4. Which of the following animals are considered ruminants? a. Cattle b. Sheep c. Deer d. All of the above 5. What component is considered the first “stomach” of the ruminant? a. Rumen b. Reticulum c. Omasum d. Abomasum Section 2. Prehension, Salivation and Rumination 1. Which of the following is not present in ruminants? a. Upper incisors b. Lower incisors c. Dental pad d. Premolars 2. How many liters of saliva can a steer produce in a day? a. 10 liters b. 25 liters c. 50 liters d. 100 liters 2 3. Which of the following is not abundantly present in saliva? a. Water b. Minerals c. Digestive enzymes d. All of the above 4. Ruminants chew food: a. Using molars and premolars b. On one side of the jaw and then the other c. -

Development of an Experimental Approach to Measure Vitamin B12 Production and Absorption in Sheep

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lincoln University Research Archive DEVELOPMENT OF AN EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH TO MEASURE VITAMIN B12 PRODUCTION AND ABSORPTION IN SHEEP A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Lincoln University NEW ZEALAND by M. R. Ludemann Lincoln University NEW ZEALAND 2009 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Development of an experimental approach to measure vitamin B12 production and absorption in sheep Abstract Clinical diagnosis of vitamin B12/cobalt (Co) deficiency is difficult due to the unspecific nature of the clinical symptoms. The apparent increase in vitamin B12 deficiency in New Zealand in the late 1990’s made it clear that health providers were very reliant on plasma reference ranges to diagnose deficiency. However, the lack of quantitative data of what these reference ranges represent in terms of supply of vitamin B12, has prevented a better understanding of the metabolism of vitamin B12 within sheep. This thesis describes the development of an experimental approach to measure vitamin B12 production and absorption in sheep. The model was then used to investigate whether the type of carbohydrate source affects vitamin B12 production and/or absorption. In the first trial (Chapter 4), an adaptation of the repletion technique of Suttle (1974) for copper was used. Previously vitamin B12 depleted sheep were maintained on a diet of 400 g DM meadow hay and 250 g DM crushed barley and which provided a daily intake of 0.03 mg Co. -

Ruminant Animal? Many Different Species of Ruminant Animals Are Found Around the World

What is a Ruminant Animal? Many different species of ruminant animals are found around the world. Ruminants include cattle, sheep, goats, buffalo, deer, elk, giraffes and camels. These animals all have a digestive system that is uniquely different from our own. Instead of one compartment to the stomach they have four. Of the four compartments the rumen is the largest section and the main digestive centre. The rumen is filled with billions of tiny microorganisms that are able to break down grass and other coarse vegetation that animals with one stomach (including humans, chickens and pigs) cannot digest. Ruminant animals do not completely chew the grass or vegetation they eat. The partially chewed grass goes into the large rumen where it is stored and broken down into balls of “cud”. When the animal has eaten its fill it will rest and “chew its cud”. The cud is then swallowed once again where it will pass into the next three compartments—the reticulum, the omasum and the true stomach, the abomasum. Dairy calves have a four-part stomach when they are born. However, they function primarily as a monogastric (simple-stomached) animal during the first part of their lives. At birth the first three compartments of a calf’s stomach—rumen, reticulum, and omasum—are inactive and undeveloped. As the calf grows and begins to eat a variety of feeds, its stomach compartments also begin to grow and change. The abomasum constitutes nearly 60 percent of the young calf’s stomach, decreasing to about 8 percent in the mature cow. The rumen comprises about 25 percent of the young calf’s stomach, increasing to 80 percent in the mature cow. -

Chronic Wasting Due to Liver and Rumen Flukes in Sheep

animals Review Chronic Wasting Due to Liver and Rumen Flukes in Sheep Alexandra Kahl 1,*, Georg von Samson-Himmelstjerna 1, Jürgen Krücken 1 and Martin Ganter 2 1 Institute for Parasitology and Tropical Veterinary Medicine, Freie Universität Berlin, Robert-von-Ostertag-Str. 7-13, 14163 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] (G.v.S.-H.); [email protected] (J.K.) 2 Clinic for Swine and Small Ruminants, Forensic Medicine and Ambulatory Service, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Foundation, Bischofsholer Damm 15, 30173 Hannover, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Chronic wasting in sheep is often related to parasitic infections, especially to infections with several species of trematodes. Trematodes, or “flukes”, are endoparasites, which infect different organs of their hosts (often sheep, goats and cattle, but other grazing animals as well as carnivores and birds are also at risk of infection). The body of an adult fluke has two suckers for adhesion to the host’s internal organ surface and for feeding purposes. Flukes cause harm to the animals by subsisting on host body tissues or fluids such as blood, and by initiating mechanical damage that leads to impaired vital organ functions. The development of these parasites is dependent on the occurrence of intermediate hosts during the life cycle of the fluke species. These intermediate hosts are often invertebrate species such as various snails and ants. This manuscript provides an insight into the distribution, morphology, life cycle, pathology and clinical symptoms caused by infections of liver and rumen flukes in sheep. -

Nutrition Digestive Systems

4-H Animal Science Lesson Plan Nutrition Level 2, 3 www.uidaho.edu/extension/4h Digestive Systems Sarah D. Baker, Extension Educator Goal (learning objective) Pre-lesson preparation Youth will learn about the differences, parts and Purchase supplies (bread, soda, orange juice, functions between ruminant and monogastric diges- Ziploc baggies) tive systems. Make copies of Handouts 1, 2, and 3 for group Supplies Prepare bread slices Copies of Handout 1 “Ruminant vs Monogastric Make arrangements to do the meeting in a lo- Digestive System” make enough copies for group cation that has internet connection, tables, and Copies of Handout 2 “Ruminant Digestive System chairs – Parts and Functions” make enough copies for Read/review lesson group Watch video Copies of Handout 3 “Monogastric Digestive Sys- Test computer/internet connection and video be- tem – Parts and Functions” make enough copies fore meeting https://youtu.be/JSlZjgpF_7g for group Computer (may need speakers depending on facil- Lesson directions and outline ity and group size) Share the following information with the youth: Internet connection to view YouTube video The definition of digestion is the process of break- Slices of bread cut into 4 squares (each member ing down food by mechanical and enzymatic action in will need one square of bread) the stomach and intestines into substances that can be used by the body. The digestive system performs five Sandwich size Ziploc baggies (one bag for each major functions: member) 1. Food intake One, three-ounce cup for holding liquid (one cup for each member) 2. Storage 1 Liter of bottle of soda 3. -

Notes on Ruminant Ecology and Evolution and Rumination

Notes on Ruminant Ecology and Evolution and Rumination Although the nature of ruminant evolution is still disputed, current theory based on genetic analysis suggests that the abomasum is evolutionarily the oldest compartment, the rumen evolved some time after the abomasums, and the omasum is the evolutionarily youngest stomach compartment. In addition According to the Journal of Dairy Science, volume 93, issue 4, the first ruminants evolved about 50 million years ago and were small (<5kg) forest dwelling omnivores. In contrast, the first marsupials and their digestive systems split from egg laying mammals about 120 million years ago. Today there are almost 200 living ruminant species in 6 families. Wild ruminants number about 75 million, range from about 2 to more than 800 kg, and generally prefer at least some browse in their diets. Nine species have been domesticated in the last 10,000 years. Their current combined population numbers 3.6 billion. In contrast to wild ruminants, domestic species naturally prefer at least some grass in their diets, and are of large body weight (BW; roughly from 35 to 800 kg), and excepting reindeer, belong to one family (Bovidae). This portion of The Grazing Academy will compare some of today’s common digestive systems and the look more closely at ruminant digestion in our domesticated species. Ruminants take their name from the important digestive process called rumination that allows for rapid ingestion of feed and completion of chewing at a later time. There are four steps to the rumination process: regurgitation, remastication, resalivation, and reswallowing. In cattle, rumination occupies up to 8 hours of the day, with one rumination cycle requiring about one minute. -

Digestion of Feeds in the Milk-Fed Calf

3 Digestion of feeds in the milk-fed calf This chapter describes the various processes of digestion in the milk-fed calf. The main points in this chapter • The adult animal requires a fully functioning rumen to digest the fibrous feeds. The rumen is undeveloped in newborn calves, which depend on abomasal digestion until weaned off milk. • Milk bypasses the rumen via the oesophageal groove where it forms a clot and is digested in the abomasum. • Rumen development depends on the intake of solid feeds, which stimulate the rumen wall to absorb feed nutrients. • Rumination, or ‘chewing the cud’, is a good sign of rumen development in milk-fed calves. • The inclusion of roughage in the diet allows for earlier weaning. However, calves must consume high energy/protein concentrates for growth as well as rumen development. If all calves could be reared by their natural mothers, there would be little need for this book. Most beef cows do a good job of rearing their own offspring, provided due care is paid to their feeding and health. The first essential of good husbandry in rearing calves is to keep them alive and fit enough to perform well later on (Moran 2002). To do this, farmers need to understand the development of the calf’s digestive tract and the basic concepts of how calves digest their food. This is illustrated in Figure 3.1. 3.1 The calf digestive tract An adult ruminant needs four functional stomachs to give it the ability to use the wide range of fibrous feeds available. The reticulum and the rumen harbour millions of microbes, which ferment and digest plant material. -

Bloat in Young Calves and Other Pre-Ruminant Livestock

Bloat In Young Calves and Other Pre-ruminant Livestock Rob Costello Dairy Technical Specialist Animals can bloat due to a variety of contributing Rumen Development – Changes in Digestive factors. However, the common thread through all Function and Structure bloat cases is production of gas by organisms in the digestive tract. Feed equipment, feed temperature, The pre-ruminant stomach is made up of the same feed ingredients, amount fed, feeding frequency, four structures or compartments as the adult water availability, weather, stress etc., may be ruminant stomach. At birth, the abomasum is the involved, but they do not cause bloat by themselves. dominant structure while the rumen is basically non Organisms, and not necessarily the pathogenic ones, functional. As the calf consumes various feeds and produce the gas that causes bloat. Keeping these water, its rumen gradually develops and increases in relationships in perspective can be a big help when it size and digestive function. Bloat can affect either comes to figuring out how various components fit the abomasum or the rumen. Since the nature of together to create a specific bloat situation. abomasal bloat is quite different from that of ruminal bloat, it is important to have some understanding of Susceptibility of individual animals to bloat is what’s happening inside the calf’s stomach as the variable and genetics may play a part in some cases. calf grows from a pre-ruminant into a ruminant Bloat can be a chronic problem on some farms and animal. never occur on others. Heifer growers that raise calves for more than one client or from more than Figure 1 shows changes in the calf’s stomach from one farm location may notice that calves from one birth to about 8 weeks of age, by which time many farm regularly have bloat problems while calves dairy calves have been weaned. -

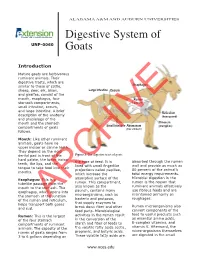

Digestive System of Goats 3 References

ALABAMA A&M AND AUBURN UNIVERSITIES Digestive System of UNP-0060 Goats Introduction Mature goats are herbivorous ruminant animals. Their digestive tracts, which are similar to those of cattle, Esophagus sheep, deer, elk, bison, Large Intestine Cecum and giraffes, consist of the mouth, esophagus, four Rumen stomach compartments, (paunch) small intestine, cecum, and large intestine. A brief Reticulum description of the anatomy (honeycomb) and physiology of the mouth and the stomach Omasum Small Intestine Abomasum (manyplies) compartments of goats (true stomach) follows. Mouth: Like other ruminant animals, goats have no upper incisor or canine teeth. They depend on the rigid dental pad in front of the Figure 1. The digestive tract of goats. hard palate, the lower incisor the type of feed. It is absorbed through the rumen teeth, the lips, and the lined with small fingerlike wall and provide as much as tongue to take food into their projections called papillae, 80 percent of the animal’s mouths. which increase the total energy requirements. Microbial digestion in the Esophagus: This is a absorptive surface of the rumen is the reason that tubelike passage from the rumen. This compartment, ruminant animals effectively mouth to the stomach. The also known as the use fibrous feeds and are esophagus, which opens into paunch, contains many maintained primarily on the stomach at the junction microorganisms, such as roughages. of the rumen and reticulum, bacteria and protozoa, helps transport bothARCHIVE gases that supply enzymes to Rumen microorganisms also and cud. break down fiber and other feed parts. Microbiological convert components of the feed to useful products such Rumen: This is the largest activities in the rumen result as essential amino acids, of the four stomach in the conversion of the B-complex vitamins, and compartments of ruminant starch and fiber of feeds to vitamin K. -

Collectins and Galectins in the Abomasum of Goats Susceptible and Resistant T to Gastrointestinal Nematode Infection ⁎ Bárbara M.P.S

Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports 12 (2018) 99–105 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vprsr Original article Collectins and galectins in the abomasum of goats susceptible and resistant T to gastrointestinal nematode infection ⁎ Bárbara M.P.S. Souzaa, , Sabrina M. Lamberta, Sandra M. Nishia, Gustavo F. Saldañab, Geraldo G.S. Oliveirac, Luis S. Vieirad, Claudio R. Madrugaa, Maria Angela O. Almeidaa a Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Biology, School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, Federal University of Bahia, Salvador, BA, Brazil b Institute for Research on Genetic Engineering and Molecular Biology (INGEBI-CONICET), Laboratory of Molecular Biology of Chagas Disease, Buenos Aires, Argentina c Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Immunology, Research Center of Gonçalo Muniz, Fiocruz, BA, Brazil d National Research Center of Goats and Sheep, Embrapa, Sobral, CE, Brazil ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Originally described in cattle, conglutinin belongs to the collectin family and is involved in innate immune Innate immunity defense. It is thought that conglutinin provides the first line of defense by maintaining a symbiotic relationship Lectins with the microbes in the rumen while inhibiting inflammatory reactions caused by antibodies leaking into the Helminth bloodstream. Due to the lack of information on the similar lectins and sequence detection in goats, we char- Ruminants acterized the goat conglutinin gene using RACE and evaluated the differences in its gene expression profile, as PCR well as in the gene expression profiles for surfactant protein A, galectins 14 and 11, interleukin 4 and interferon- gamma in goats. -

Diagnosis and Management of Abomasal Disorders in Cattle

Mansoura University Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Dept. of Surgery, Anesthesiology &Radiology Diagnosis and Management of Abomasal Disorders in Cattle Thesis presented By El-sayed Ahmed Awad El-shafaey (B.V.Sc.,2002, Mansoura University) Under supervision of Prof. Dr. Dr. Adel El-Tabey Ibrahim Zaghloul Gamal Ibrahim Abd El-Fatah Karrouf Professor and Head of Surgery, Anesthesiology Associate Prof.of Surgery, Anesthesiology & & Radiology Dept., Fac. Vet. Med., Mansoura Radiology Fac. Vet. Med., Mansoura University University Prof. Dr. Taha Abdel-Monaem Fouda Professor of Internal Medicine Fac. Vet. Med., Mansoura University Submitted to Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Mansoura University For the Degree of Master of Vet. Med. Sciences (Veterinary Surgery) (2007) Acknowledgment Acknowledgment First of all I am greatly indebted in my work and success to our merciful "Allah" who gave me the ability to terminate this work. Great appreciation profound gratitude and deepest thanks are offered to Prof. Dr. Adel E.I. Zaghloul, Prof. and head of Surgery Dept. Fac. Vet. Med., Mansoura University for his kind supervision, valuable advice, encouragement, keen suggestion during the course of this study and revision all the details that enabled me to finish this work. Grateful thanks, deep-seated sincere appreciation are also extended to Dr. Gamal I. A. Karrouf, Associate. Prof. of surgery . Fac. Vet. Med., Mansoura University for his help, co-operation and supervision, continuous guidance, unlimited help, valuable advice, encouragement, keen suggestion during the course of this study and revision all the details that enabled me to finish this work. Great appreciation profound gratitude and thanks offered to Prof. Dr. Taha A. -

Digestive System and Nutrient Needs of Meat Goats

AS-628-W AGEXTENSIONRICULTURE Casey Cromer, Animal Sciences Digestive System and student Mike Neary, Nutrient Needs of Meat Goats Extension Small Meat goats are ruminants and get the four stomach compartments that make this Ruminant Specialist nutrients they need through a wide variety possible are the reticulum, rumen, omasum, of feedstuffs. Because of this, producers must and abomasum (Figure 1). thoroughly understand digestive physiology and nutrition before they can develop an When a goat eats, the feed or forage first efficient and economical nutrition program enters the reticulum. Here honeycomb papil- for meat goats. Growth rate, reproductive lae (projections in a honeycomb pattern that performance, animal well-being, and line the rumen) help separate particles based economic efficiency of a goat operation all on size. Large feed particles are sent back into depend on the herd nutrition plan. This the rumen for further digestion, and small publication describes the digestive system particles are sent to the third digestive com- and nutrient requirements of meat goats and partment. Large particles can also be regurgi- the relationships between nutrition, animal tated and re-chewed to make them smaller so productivity, and producer profitability. that they are easier to digest. Small Ruminant Digestion The most well-known gastro-intestinal com- partment of the ruminant is the rumen. The Purdue Animal Sciences A ruminant has a four-compartment stom- rumen is a large fermentation vat where fatty www.ag.purdue.edu/ANSC ach. Unlike monogastric (simple stomach) acids, carbohydrates, proteins, and other nu- animals, ruminants can digest a multitude trients are broken down. Microbes within the of feeds, particularly those high in fiber.