Historical Research Report on the Kingsland Point Lighthouse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NLM Newsletter Summer 2020

National Lighthouse Museum Summer 2020 newsletter CALLING ALL FIG LOVERS : JOIN US FOR OUR VIRTUAL FIG FEST 9/15/20 Photo Credits: NLM, Staten Island Real Estate google.com & SI Advance Photo Credits: NLM, nature.com, heywood.com National Lighthouse Museum “To preserve and educate on the maritime heritage of Lighthouses & Lightships for generations to come...” A Letter from Our Executive Director Dear National Lighthouse Museum Friends, Welcome to our Summer 2020 National Lighthouse Museum Newsletter! It is so hard to believe we are still enmeshed in this pandemic, struggling to survive against all odds. As New York enters Phase 4, Museums, along with other indoor facilities, remain in lock down mode. Ready to get the go ahead, under the “new norm rules”, we have also received many requests for our seasonal lighthouse boat tours, but unfortunately each one - most recently our famed Signature- Ambrose Channel Tour, scheduled for Lighthouse Weekend - August 9th., had to be cancelled. Notwithstanding, we are proud to announce that despite our Museum closure back in mid-March, we have accomplished some exciting on- line/ virtual public programs: Two Zoom lectures -“Lights, Camera, Action - tips on photographing a Lighthouse!” with special thanks to Todd Vorenkamp -“The Union Blockade during the American Civil War” - with a big thanks to our lecturer, Wade R.Goria, featured in a three-hour series, thanks to the generosity of cinematographer, Jon Roche, Oliver Anderson, 2nd Camera, and editor, Daniel Amigone Twelve” Lighthouse of the Week” virtual Tuesday presentations, with a special thanks to Kraig Anderson creator of lighthousefriends.com and coordinated by Jean Coombs. -

Fire Island Light Station

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES--COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Fire Island Light Station _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN Bay Shore 0.1. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New York 36 Suffolk HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT -XPUBLIC OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) ^.PRIVATE X.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL XPARK _XSTRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS iLYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) National Park Service, Morth Atlantic Region STREET & NUMBER 15 State Street CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Massachusetts COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Land Acquisition Division, National Park Service, North Atlantic CITY. TOWN STATE Boston, Massachusetts TITLE U.S. Coast Guard, 3d Dist., "Fire Island Station Annex" Civil Plot Plan 03-5523 DATE 18 June 1975, revised 8-7-80 .^FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS- Nationa-| park Service, North Atlantic Regional Office CITY, TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS . X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE_____ X.FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Fire Island Light Station is situated 5 miles east of the western end of Fire Island, a barrier island off the southern coast of Long Island. It consists of a lighthouse and an adjacent keeper's quarters sitting on a raised terrace. -

NELL NEWS July/August

NELL NEWS July/August Happy 4th NELL T-Shirts with a New Logo These shirts are available in S, M, L, XL and XXL They come in a variety of colours Merchandise chairs Ellen & Bob Granoth have limited stock but these shirts can be ordered in any size and the colour of your choice [email protected] June 2019 NELL Members: The following is updated information regarding our trip to Downeast Maine the weekend of September 20-22, 2019. Everyone is required to have a passport book or card if crossing to/from Campobello Island, or if you plan to visit any other area in Canada. Saturday, September 21, 2019 9:00 AM- NoonEastport Windjammers, 104 Water Street, Eastport, ME will take us on a Cruise out ofEastportto view Lubec Channel Lighthouse, Mulholland Lighthouse, West Quoddy Head Light, and Head Harbour Light Station (East Quoddy), along with four (4)lights in New Brunswick, CA (if the weather cooperates): Southwest Wolf Island Lighthouse, Pea Point Lighthouse, Green's Point (Letete Passage) Lighthouse, and Bliss Island Lighthouse. We’ll also see the Old Sow, the largest tidal whirlpool in the western hemisphere. The cruise will be approximately three (3) hours. As the boat has a maximum capacity of 49 passengers, it is essential that you confirm your attendance with Linda Sherlock as soon as possible to reserve your spot. 12:30 PM – 2:30 PMLunch and Business Meetingat the Robbinston Historical Society, 505 U. S Route 1, Robbinston, ME. Lighthouse aficionado and editor and publisher of Lighthouse Digest magazine, Timothy Harrison, will be our guest speaker.Lunch will be provided. -

Chesapeake Bay and Coastal Lighthouses/Lightships/ Lifesaving Station Information

Chesapeake Bay and Coastal Lighthouses/Lightships/ Lifesaving Station Information This information was provided by personnel from the various organizations listed below and may be subject to change. Look for a copy of this list on our website www.cheslights.org. Assateague Lighthouse Portsmouth Lightship Located in the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge Located at 435 Water Street at intersection of London & Water (NWR), Virginia. streets, Portsmouth, VA. Phone: Chincoteague NWR - (757) 336-6122 NOTE: Lightship scheduled to open on Memorial Day. Hours: The tower will be open for climbing from 9 am to 3 Phone: Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Museum - (757) 393-8591 pm on the following weekends: & Lightship (757) 393-8741. May 8 & 9, June 5 & 6, July 10 & 11, August 21 & 22, Contact: Mrs. Hanes September 4 & 5, and October 9 & 10. If ownership of the Hours: Open Tuesday to Saturday 10 am to 5 pm & lighthouse changes, the dates could be cancelled. Suggestion Sunday 1 pm to 5 pm. Open on Monday’s Memorial Day - Bring mosquito repellant. through Labor Day and holiday’s 10 am – 5 pm. Cost: $10 per vehicle to enter the Refuge - pass is good for Cost: $3.00 for museum and lightship seven days - OR- $15 for a yearlong vehicle pass. No charge Website: www.portsmouth.va.us/tourism/docs/tourism6.htm to climb the lighthouse. (look under HISTORIC SITES) NOTE: The original Fresnel lens from the Assateague Lighthouse is on display at the nearby Oyster and Maritime Old Coast Guard Station Museum Museum, located at 7125 Maddox Blvd, Chincoteague, VA. Located at 24th Street and Atlantic Avenue Phone: (757) 336-6117 Virginia Beach, VA. -

Mount Desert Rock Light

Lighthouse - Light Station History Mount Desert Rock Light State: Maine Town: Frenchboro Year Established: August 25, 1830 with a fixed white light Location: Twenty-five miles due south of Acadia National Park GPS (Global Positioning System) Latitude, Longitude: 43.968764, -68.127797 Height Above Sea Level: 17’ Present Lighthouse Built: 1847 – replaced the original wooden tower Architect: Alexander Parris Contractor: Joseph W. Coburn of Boston Height of Tower: 58’ Height of Focal Plane: 75’ Original Optic: 1858 - Third-order Fresnel lens Present Optic: VRB-25 Automated: 1977 Keeper’s House – 1893 Boathouse - 1895 Keeper History: Keeper 1872 – 1881: Amos B. Newman (1830-1916) Disposition: Home of College of the Atlantic’s Edward McC. Blair Marine Research Station. Mount Desert Rock is a remote, treeless island situated approximately 25 nautical miles south of Bar Harbor, Maine. "…Another important Maine coast light is on Mount Desert Rock. This is one of the principal guides to Mount Desert Island, and into Frenchman's and Blue Hill Bays on either side. This small, rocky islet which is but twenty feet high, lies seventeen and one half miles southward of Mount Desert Island, eleven and one half miles outside of the nearest island and twenty-two miles from the mainland. It is one of the most exposed lighhouse locations on our entire Atlantic coast. The sea breaks entirely over the rock in heavy gales, and at times the keepers and their families have had to retreat to the light tower to seek refuge from the fury of the storms. This light first shone in 1830. -

Lighthouse Scenic Tours

LIGHTHOUSE SCENIC TOURS Towering over 300 miles of picturesque Rock Island Pottawatomie Lighthouse Lighthouses shoreline, you will find historic Please contact businesses for current tour schedules and pick up/drop off locations. Bon Voyage! lighthouses standing testament to Door Washington Island County’s rich maritime heritage. In the Bay Shore Outfitters, 2457 S. Bay Shore Drive - Sister Bay 920.854.7598 19th and early 20th centuries, these Gills Rock Plum Island landmarks of yesteryear assisted sailors Ellison Bay Range Light Bay Shore Outfitters, 59 N. Madison Ave. - Sturgeon Bay 920.818.0431 Chambers Island Lighthouse Pilot Island in navigating the lake and bay waters Lighthouse of the Door Peninsula and surrounding Sister Bay Cave Point Paddle & Pedal, 6239 Hwy 57 - Jacksonport 920.868.1400 Rowleys Bay islands. Today, many are still operational Ephraim and welcome visitors with compelling Eagle Bluff Lighthouse Cana Island Lighthouse Door County Adventure Center, stories and breathtaking views. Relax and Fish Creek 4497 Ploor Rd. - Sturgeon Bay 920.746.9539 step back in time. Plan your Door County Baileys Harbor Egg Harbor Door County Adventure Rafting, 4150 Maple St. - Fish Creek 920.559.6106 lighthouse tour today. Old Baileys Harbor Light Baileys Harbor Range Light Door County Kayak Tours, 8442 Hwy 42 - Fish Creek 920.868.1400 Jacksonport Visitors can take advantage of additional Carlsville access to locations not typically open Sturgeon Bay Door County Maritime Museum, to the public during the Annual Door Sherwood Point 120 N. Madison Ave. - Sturgeon Bay 920.743.5958 County Lighthouse Festival, which will be Lighthouse held the weekends of June 11-13 & Oct Sturgeon Bay Canal Station Lighthouse Door County Tours, P.O. -

Foghorn-Quarter 2-2012

FogHorn WestportWestport----SouthSouth Beach Historical Society Newsletter 2nd Quarter 2012 The mission of the Grays Harbor Lighthouse named Pacific NW “BEST Westport South Beach LIGHTHOUSE” by KING 5’s Evening Magazine! Historical Society By Sue Shidaker is to preserve and Westport did itself proud when Evening Magazine announced the winners in the interpret the history of “Best Northwest Escapes” 2012 contest. Known for a variety of special features, the the South Beach, community was affirmed as “special” in several areas when the votes were counted. with an emphasis on Most notable to the Historical Society, voters statewide chose our very own Grays natural resources and Harbor Lighthouse as the “Best Lighthouse,” from among 25 nominated lighthouses along the Pacific Northwest coast and San Juan Islands. advocating for In addition to the lighthouse, Evening Magazine also awarded four other “bests” to preservation of our the community of Westport. Since fishing is at the heart of Westport’s activity and harbor local historic life, it was not surprising to have a local charter company, Westport Charters, voted “Best structures in our mari- Fishing Charter” in the contest. Likewise, surfers’ love of the Westport waves brought time community. another award being named “Best Surfing Destination.” A special feature of any trip to the coast, the Westport Winery was voted the 2012 winner of the Best Wine Tour award. The winery is noted for its tours, dining options, a gift shop, and good wines, as well as for its practice of supporting the community efforts by donating a portion of the proceeds of each variety of wine to a selected community or- ganization. -

Celebrating 30 Years

VOLUME XXX NUMBER FOUR, 2014 Celebrating 30 Years •History of the U.S. Lighthouse Society •History of Fog Signals The•History Keeper’s of Log—Fall the U.S. 2014 Lighthouse Service •History of the Life-Saving Service 1 THE KEEPER’S LOG CELEBRATING 30 YEARS VOL. XXX NO. FOUR History of the United States Lighthouse Society 2 November 2014 The Founder’s Story 8 The Official Publication of the Thirty Beacons of Light 12 United States Lighthouse Society, A Nonprofit Historical & AMERICAN LIGHTHOUSE Educational Organization The History of the Administration of the USLH Service 23 <www.USLHS.org> By Wayne Wheeler The Keeper’s Log(ISSN 0883-0061) is the membership journal of the U.S. CLOCKWORKS Lighthouse Society, a resource manage- The Keeper’s New Clothes 36 ment and information service for people By Wayne Wheeler who care deeply about the restoration and The History of Fog Signals 42 preservation of the country’s lighthouses By Wayne Wheeler and lightships. Finicky Fog Bells 52 By Jeremy D’Entremont Jeffrey S. Gales – Executive Director The Light from the Whale 54 BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS By Mike Vogel Wayne C. Wheeler President Henry Gonzalez Vice-President OUR SISTER SERVICE RADM Bill Merlin Treasurer Through Howling Gale and Raging Surf 61 Mike Vogel Secretary By Dennis L. Noble Brian Deans Member U.S. LIGHTHOUSE SOCIETY DEPARTMENTS Tim Blackwood Member Ralph Eshelman Member Notice to Keepers 68 Ken Smith Member Thomas A. Tag Member THE KEEPER’S LOG STAFF Head Keep’—Wayne C. Wheeler Editor—Jeffrey S. Gales Production Editor and Graphic Design—Marie Vincent Copy Editor—Dick Richardson Technical Advisor—Thomas Tag The Keeper’s Log (ISSN 0883-0061) is published quarterly for $40 per year by the U.S. -

Building a Successful Lighthouse Preservation Society

BUILDING A SUCCESSFUL LIGHTHOUSE PRESERVATION SOCIETY DeTour Reef Light Preservation Society (DRLPS) presented by Jeri Baron Feltner at Keep the Lights On! Strategies for Saving Michigan’s Lighthouses Lighthouse Preservation Workshop Sponsored by the State Historic Preservation Office & The Michigan Lighthouse Project at the Forum of the Michigan Library and Historical Center Lansing, Michigan November 6, 1998 Thank you Michael, it is a pleasure to be here today representing the DeTour Reef Light Preservation Society team at this first historic lighthouse workshop. Part of our team is here today - Carol Melvin our Finance Committee Chairperson, my husband Chuck Feltner our Chief Historian, and Dick Moehl our founder and one of our Directors. Other members are my brother Larry Baron, the video man, Marilyn Fischer, President of the Gulliver Historical Society, Sandy Planisek Director of the GLLM, John Wagner and John Andree. We come here today from the front lines of the creating and operating of a successful lighthouse preservation society. We learned a lot, and I would like to share with you today what we did to earn the honor of being the new caretaker of one of America’s unique resources -- the DeTour Reef Lighthouse. The AGENDA includes: 1) Historical Background 2) The Situation Today 3) DRLPS Purpose 4) Accomplishments 5) Goals 6) The Challenge for the Future 7) Closing Remarks 1) HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Let me give you a brief historical background. The original Lighthouse that is no longer in existence, was the DeTour Point Light established onshore in 1847 and rebuilt in 1861. This Light was replaced DeTour Reef Light Preservation Society - P. -

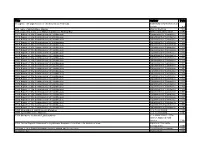

Lighthouse Bibliography.Pdf

Title Author Date 10 Lights: The Lighthouses of the Keweenaw Peninsula Keweenaw County Historical Society n.d. 100 Years of British Glass Making Chance Brothers 1924 137 Steps: The Story of St Mary's Lighthouse Whitley Bay North Tyneside Council 1999 1911 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1911 1912 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1912 1913 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1913 1914 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1914 1915 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1915 1916 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1916 1917 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1917 1918 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1918 1919 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1919 1920 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1920 1921 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1921 1922 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1922 1923 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1923 1924 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1924 1925 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1925 1926 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1926 1927 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1927 1928 Report of the Commissioner of -

INTRODUCTION to CHART PLOTS - Version 3

INTRODUCTION TO CHART PLOTS - Version 3 Operational Level 3M/2M 1600T 500T Ocean or Near Coastal The following pages contain references to various references to points of land, lights, buoys, etc. that are used by the National Maritime Center (NMC) in their chart plots solutions. Learning where these points can be found on the individually referenced chart will be of aid to you in solving the chart plot more quickly and efficiently. As you find each point a check off box is provided so you know when you have covered them all. Good luck on your chart plots. LAPWARE, LLC BIS - Introduction to Plot 3M/2M UNL The following references are based on chart 13205TR, 500T / 1600T Block Island Sound, and the supporting pubs. Lights or The following points, lights, buoys, etc. are listed in Points of Land ALPHABETICAL order. Bartlett Reef Light Block Island Grace Point Block Island North Light (Tower) Block Island Southeast Light Buoy "PI" Cerberus Shoal "9" Buoy Fisher's Island (East Harbor Cupola) and (East Point) Fishers Island Sound Gardiners Point Gardiners Point Ruins - 1 mile North of Gardiners Island Great Eastern Rock Great Salt Pond Green Hill Point Latimer Reef Light Little Gull Island Light Montauk Point Montauk Point Light and Lighthouse Mt. Prospect Antenna Mystic Harbor New London Harbor North Dumpling Island Light Point Judith Harbor of Refuge (Main Breakwater Center Light) Point Judith Light Providence, RI Race Rock Light Shagwong Pt. Stongington Outer Breakwater Light in line with Stonington Inner The Race Watch Hill Light and Buoy "WH" Watch Hill Point (and South Tip) Review the following: Watch Hill Point and Point Judith coastline Look up or determine the following: Reference Light List and/or Coast Pilots Block Island Sound Chart Plot Page 2 © Copyright 2009 - LAPWARE, LLC BIS - Introduction to Plot 3M/2M UNL The following references are based on chart 13205TR, 500T / 1600T Block Island Sound, and the supporting pubs. -

Ponce De Leon Inlet Lighthouse Preservation Association

1 Ponce de Leon Inlet Lighthouse Preservation Association Fiscal Year 2018-2019 Annual Report Dedicated to the continued preservation and dissemination of the maritime and social history of the historic Ponce de Leon Inlet Light Station since its inception in 1972, the Preservation Association works diligently to achieve its mission of preserving and disseminating the maritime and social history of the Ponce Inlet Lighthouse each fiscal year. The following report outlines the work completed during the fiscal period from October 1, 2018 through September 30, 2019. While this document provides the reader with a fairly comprehensive outline of scheduled and non-scheduled work completed by the maintenance, programs, curatorial, gift shop, and administrative departments, it should not be considered a complete overview of all work completed. Ordinary day to day tasks associated with general facility maintenance (including routine daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, and annual duties) is included in the maintenance department report beginning on page 11. Table of Contents Page 2: Gift Shop Report Page 11: Maintenance Department Report Page 17: Curatorial Department Report Page 24: Programs Department Report Page 31: Administrative Department Report 2 Gift Shop Report for FY 2018-2019 Gift Shop Operations Summary: The Association’s gift shop is responsible for generating and processing the majority of the association’s annual revenue including admission and merchandise sales, annual membership dues, and private donations. The gift shop employs 8-11 personnel at various times throughout the year. The gift shop’s staff roster consists of one full-time manager, one full-time assistant-manager, one full-time lead sales associate and up to 8 part-time sales associates.