The Performative Museum Designing a Total Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NLM Newsletter Summer 2020

National Lighthouse Museum Summer 2020 newsletter CALLING ALL FIG LOVERS : JOIN US FOR OUR VIRTUAL FIG FEST 9/15/20 Photo Credits: NLM, Staten Island Real Estate google.com & SI Advance Photo Credits: NLM, nature.com, heywood.com National Lighthouse Museum “To preserve and educate on the maritime heritage of Lighthouses & Lightships for generations to come...” A Letter from Our Executive Director Dear National Lighthouse Museum Friends, Welcome to our Summer 2020 National Lighthouse Museum Newsletter! It is so hard to believe we are still enmeshed in this pandemic, struggling to survive against all odds. As New York enters Phase 4, Museums, along with other indoor facilities, remain in lock down mode. Ready to get the go ahead, under the “new norm rules”, we have also received many requests for our seasonal lighthouse boat tours, but unfortunately each one - most recently our famed Signature- Ambrose Channel Tour, scheduled for Lighthouse Weekend - August 9th., had to be cancelled. Notwithstanding, we are proud to announce that despite our Museum closure back in mid-March, we have accomplished some exciting on- line/ virtual public programs: Two Zoom lectures -“Lights, Camera, Action - tips on photographing a Lighthouse!” with special thanks to Todd Vorenkamp -“The Union Blockade during the American Civil War” - with a big thanks to our lecturer, Wade R.Goria, featured in a three-hour series, thanks to the generosity of cinematographer, Jon Roche, Oliver Anderson, 2nd Camera, and editor, Daniel Amigone Twelve” Lighthouse of the Week” virtual Tuesday presentations, with a special thanks to Kraig Anderson creator of lighthousefriends.com and coordinated by Jean Coombs. -

Farsund & Listalandet

Live Camera CITY HARBOUR [Farsund2000] [GPS] [Photo-PostCard-NEW] [HELP] [About us] [NewsLetter] [Tell-A-Friend] [GuestHarbour ] [Weather] [PhotoGallery] [Members] [Forening / Lag] [©CopyRight] [Admin] - Chose County - Chose Counsil N -Chose AirPort.No Velkommen til VisitEurope.NO Akershus Agdenes Alta Airport Aust-Agder Alstahaug Andøya Her kan din bedrift profileres med både oppføringer og bannere til svært Buskerud Alta Bardufoss gunstige priser og betingelser. Portalen er tilknyttet den europeiske Finnmark Alvdal Båtsfjord hovedportalen VisitEurope.TV som representerer alle land i Europa. Vi inkluderer gode og viktige funksjonaliteter uten ekstra betaling. Bestill nå eller få mer informasjon ved å klikke på overskriften. Velkomm channel: - Turn ON Radio -------> Farsund & Listalandet 1200 EPostCards/Photo's Welcome to Farsund! The municipality of Farsund has ca. 9.200 inhabitants, mainly concentrated on three centres of population - Farsund town, Vanse and Vestbygda. It also includes the outlying districts of Lista, Herad and Spind. Shipping, fishing and agriculture have been the main industries in the area. Today Farsund is the largest agrcultural district in the county of Vest-Agder, having 26 km2 productive land, 88 km2 forest and 17 k m2 freshwater areas. Farsund was already recognized as a trading centre in 1795, and in 1995 celebrated its 200-years jubilee with town status. Vanse: was formerly the largest centre of population in the district. Today it has 2.500 inhabitants, and some of the council offices are still situated there. Vestbygda: is built round the only harbour of any size in a particularly exposed stretch of the coast. There was a considerable emigration to the United States from this region in former times. -

Download Exchange Guide Brochure

Welcome to UiA The University of Agder (UiA) is a young responsible leadership through faculties The School of Business Why choose UiA? and dynamic university situated on the dedicated to teaching and co-creation of and Law at UiA is > NO tuition fees southern tip of Norway. We are one of the knowledge. UiA seeks to be an open and accredited by the AACSB, one of only two most modern universities in Norway and inclusive university that is characterized accredited business schools in Norway. > Courses in English at all faculties offer high-quality study programmes with by a culture of cooperation, and aims an international focus. We prepare our to be on the cutting edge of innovation, > Guaranteed Accommodation students for a lifetime of learning and of education and research. > Buddy Programme offered by ESN Campuses Faculties Research and Collaboration > Modern Facilities UiA is located on two campuses that are UiA’s seven faculties/units are: UiA has extensive collaboration with a > Safe Environment within walking distance of the city centres, range of establishments and businesses. > Faculty of Humanities and Education yet only meters away from both beaches We have partners at regional, national, > Warm summers and snowy winters and forests for running, climbing, biking, > Faculty of Health and Sport Science and international levels from both > Norway is the happiest country in the world! hiking, swimming and other activities. > Faculty of Engineering and Science private and public sectors. The university UiA campuses are meeting places which participates in several types of research stimulate to dialogue and mutual cultural > Faculty of Social Science collaborations. -

NELL NEWS July/August

NELL NEWS July/August Happy 4th NELL T-Shirts with a New Logo These shirts are available in S, M, L, XL and XXL They come in a variety of colours Merchandise chairs Ellen & Bob Granoth have limited stock but these shirts can be ordered in any size and the colour of your choice [email protected] June 2019 NELL Members: The following is updated information regarding our trip to Downeast Maine the weekend of September 20-22, 2019. Everyone is required to have a passport book or card if crossing to/from Campobello Island, or if you plan to visit any other area in Canada. Saturday, September 21, 2019 9:00 AM- NoonEastport Windjammers, 104 Water Street, Eastport, ME will take us on a Cruise out ofEastportto view Lubec Channel Lighthouse, Mulholland Lighthouse, West Quoddy Head Light, and Head Harbour Light Station (East Quoddy), along with four (4)lights in New Brunswick, CA (if the weather cooperates): Southwest Wolf Island Lighthouse, Pea Point Lighthouse, Green's Point (Letete Passage) Lighthouse, and Bliss Island Lighthouse. We’ll also see the Old Sow, the largest tidal whirlpool in the western hemisphere. The cruise will be approximately three (3) hours. As the boat has a maximum capacity of 49 passengers, it is essential that you confirm your attendance with Linda Sherlock as soon as possible to reserve your spot. 12:30 PM – 2:30 PMLunch and Business Meetingat the Robbinston Historical Society, 505 U. S Route 1, Robbinston, ME. Lighthouse aficionado and editor and publisher of Lighthouse Digest magazine, Timothy Harrison, will be our guest speaker.Lunch will be provided. -

Chesapeake Bay and Coastal Lighthouses/Lightships/ Lifesaving Station Information

Chesapeake Bay and Coastal Lighthouses/Lightships/ Lifesaving Station Information This information was provided by personnel from the various organizations listed below and may be subject to change. Look for a copy of this list on our website www.cheslights.org. Assateague Lighthouse Portsmouth Lightship Located in the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge Located at 435 Water Street at intersection of London & Water (NWR), Virginia. streets, Portsmouth, VA. Phone: Chincoteague NWR - (757) 336-6122 NOTE: Lightship scheduled to open on Memorial Day. Hours: The tower will be open for climbing from 9 am to 3 Phone: Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Museum - (757) 393-8591 pm on the following weekends: & Lightship (757) 393-8741. May 8 & 9, June 5 & 6, July 10 & 11, August 21 & 22, Contact: Mrs. Hanes September 4 & 5, and October 9 & 10. If ownership of the Hours: Open Tuesday to Saturday 10 am to 5 pm & lighthouse changes, the dates could be cancelled. Suggestion Sunday 1 pm to 5 pm. Open on Monday’s Memorial Day - Bring mosquito repellant. through Labor Day and holiday’s 10 am – 5 pm. Cost: $10 per vehicle to enter the Refuge - pass is good for Cost: $3.00 for museum and lightship seven days - OR- $15 for a yearlong vehicle pass. No charge Website: www.portsmouth.va.us/tourism/docs/tourism6.htm to climb the lighthouse. (look under HISTORIC SITES) NOTE: The original Fresnel lens from the Assateague Lighthouse is on display at the nearby Oyster and Maritime Old Coast Guard Station Museum Museum, located at 7125 Maddox Blvd, Chincoteague, VA. Located at 24th Street and Atlantic Avenue Phone: (757) 336-6117 Virginia Beach, VA. -

Mount Desert Rock Light

Lighthouse - Light Station History Mount Desert Rock Light State: Maine Town: Frenchboro Year Established: August 25, 1830 with a fixed white light Location: Twenty-five miles due south of Acadia National Park GPS (Global Positioning System) Latitude, Longitude: 43.968764, -68.127797 Height Above Sea Level: 17’ Present Lighthouse Built: 1847 – replaced the original wooden tower Architect: Alexander Parris Contractor: Joseph W. Coburn of Boston Height of Tower: 58’ Height of Focal Plane: 75’ Original Optic: 1858 - Third-order Fresnel lens Present Optic: VRB-25 Automated: 1977 Keeper’s House – 1893 Boathouse - 1895 Keeper History: Keeper 1872 – 1881: Amos B. Newman (1830-1916) Disposition: Home of College of the Atlantic’s Edward McC. Blair Marine Research Station. Mount Desert Rock is a remote, treeless island situated approximately 25 nautical miles south of Bar Harbor, Maine. "…Another important Maine coast light is on Mount Desert Rock. This is one of the principal guides to Mount Desert Island, and into Frenchman's and Blue Hill Bays on either side. This small, rocky islet which is but twenty feet high, lies seventeen and one half miles southward of Mount Desert Island, eleven and one half miles outside of the nearest island and twenty-two miles from the mainland. It is one of the most exposed lighhouse locations on our entire Atlantic coast. The sea breaks entirely over the rock in heavy gales, and at times the keepers and their families have had to retreat to the light tower to seek refuge from the fury of the storms. This light first shone in 1830. -

Lighthouse Scenic Tours

LIGHTHOUSE SCENIC TOURS Towering over 300 miles of picturesque Rock Island Pottawatomie Lighthouse Lighthouses shoreline, you will find historic Please contact businesses for current tour schedules and pick up/drop off locations. Bon Voyage! lighthouses standing testament to Door Washington Island County’s rich maritime heritage. In the Bay Shore Outfitters, 2457 S. Bay Shore Drive - Sister Bay 920.854.7598 19th and early 20th centuries, these Gills Rock Plum Island landmarks of yesteryear assisted sailors Ellison Bay Range Light Bay Shore Outfitters, 59 N. Madison Ave. - Sturgeon Bay 920.818.0431 Chambers Island Lighthouse Pilot Island in navigating the lake and bay waters Lighthouse of the Door Peninsula and surrounding Sister Bay Cave Point Paddle & Pedal, 6239 Hwy 57 - Jacksonport 920.868.1400 Rowleys Bay islands. Today, many are still operational Ephraim and welcome visitors with compelling Eagle Bluff Lighthouse Cana Island Lighthouse Door County Adventure Center, stories and breathtaking views. Relax and Fish Creek 4497 Ploor Rd. - Sturgeon Bay 920.746.9539 step back in time. Plan your Door County Baileys Harbor Egg Harbor Door County Adventure Rafting, 4150 Maple St. - Fish Creek 920.559.6106 lighthouse tour today. Old Baileys Harbor Light Baileys Harbor Range Light Door County Kayak Tours, 8442 Hwy 42 - Fish Creek 920.868.1400 Jacksonport Visitors can take advantage of additional Carlsville access to locations not typically open Sturgeon Bay Door County Maritime Museum, to the public during the Annual Door Sherwood Point 120 N. Madison Ave. - Sturgeon Bay 920.743.5958 County Lighthouse Festival, which will be Lighthouse held the weekends of June 11-13 & Oct Sturgeon Bay Canal Station Lighthouse Door County Tours, P.O. -

Foghorn-Quarter 2-2012

FogHorn WestportWestport----SouthSouth Beach Historical Society Newsletter 2nd Quarter 2012 The mission of the Grays Harbor Lighthouse named Pacific NW “BEST Westport South Beach LIGHTHOUSE” by KING 5’s Evening Magazine! Historical Society By Sue Shidaker is to preserve and Westport did itself proud when Evening Magazine announced the winners in the interpret the history of “Best Northwest Escapes” 2012 contest. Known for a variety of special features, the the South Beach, community was affirmed as “special” in several areas when the votes were counted. with an emphasis on Most notable to the Historical Society, voters statewide chose our very own Grays natural resources and Harbor Lighthouse as the “Best Lighthouse,” from among 25 nominated lighthouses along the Pacific Northwest coast and San Juan Islands. advocating for In addition to the lighthouse, Evening Magazine also awarded four other “bests” to preservation of our the community of Westport. Since fishing is at the heart of Westport’s activity and harbor local historic life, it was not surprising to have a local charter company, Westport Charters, voted “Best structures in our mari- Fishing Charter” in the contest. Likewise, surfers’ love of the Westport waves brought time community. another award being named “Best Surfing Destination.” A special feature of any trip to the coast, the Westport Winery was voted the 2012 winner of the Best Wine Tour award. The winery is noted for its tours, dining options, a gift shop, and good wines, as well as for its practice of supporting the community efforts by donating a portion of the proceeds of each variety of wine to a selected community or- ganization. -

Celebrating 30 Years

VOLUME XXX NUMBER FOUR, 2014 Celebrating 30 Years •History of the U.S. Lighthouse Society •History of Fog Signals The•History Keeper’s of Log—Fall the U.S. 2014 Lighthouse Service •History of the Life-Saving Service 1 THE KEEPER’S LOG CELEBRATING 30 YEARS VOL. XXX NO. FOUR History of the United States Lighthouse Society 2 November 2014 The Founder’s Story 8 The Official Publication of the Thirty Beacons of Light 12 United States Lighthouse Society, A Nonprofit Historical & AMERICAN LIGHTHOUSE Educational Organization The History of the Administration of the USLH Service 23 <www.USLHS.org> By Wayne Wheeler The Keeper’s Log(ISSN 0883-0061) is the membership journal of the U.S. CLOCKWORKS Lighthouse Society, a resource manage- The Keeper’s New Clothes 36 ment and information service for people By Wayne Wheeler who care deeply about the restoration and The History of Fog Signals 42 preservation of the country’s lighthouses By Wayne Wheeler and lightships. Finicky Fog Bells 52 By Jeremy D’Entremont Jeffrey S. Gales – Executive Director The Light from the Whale 54 BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS By Mike Vogel Wayne C. Wheeler President Henry Gonzalez Vice-President OUR SISTER SERVICE RADM Bill Merlin Treasurer Through Howling Gale and Raging Surf 61 Mike Vogel Secretary By Dennis L. Noble Brian Deans Member U.S. LIGHTHOUSE SOCIETY DEPARTMENTS Tim Blackwood Member Ralph Eshelman Member Notice to Keepers 68 Ken Smith Member Thomas A. Tag Member THE KEEPER’S LOG STAFF Head Keep’—Wayne C. Wheeler Editor—Jeffrey S. Gales Production Editor and Graphic Design—Marie Vincent Copy Editor—Dick Richardson Technical Advisor—Thomas Tag The Keeper’s Log (ISSN 0883-0061) is published quarterly for $40 per year by the U.S. -

Port of Bergen

Cruise Norway The complete natural experience A presentation of Norwegian destinations and cruise ports Cruise Norway Manual 2007/2008 ANGEN R W NNA : GU OTO H Index P Index 2 Presentation of Cruise Norway 2-3 Cruise Cruise Destination Norway 4-5 Norwegian Cruise Ports 6 wonderful Norway Distances in nautical miles 7 The “Norway Cruise Manual” gives a survey of Norwegian harbours Oslo Cruise Port 8 providing excellent services to the cruise market. This presentation is edited in a geographical sequence: It starts in the North - and finishes Drammen 10 in the South. Kristiansand 12 The presentation of each port gives concise information about the most 3 Small City Cruise 14 important attractions, “day” and “halfday” excursions, and useful, practical information about harbour conditions. The amount of information is limited Stavanger 16 due to space. On request, more detailed information may be obtained from Eidfjord 18 Cruise Norway or from the individual ports. The “Norway Cruise Manual” is the only comprehensive overview of Ulvik 20 Norwegian harbours and the cooperating companies that have the Bergen 22 international cruise market as their field of activity. The individual port authorities / companies are responsible for the information which Vik 24 appears in this presentation. Flåm 26 An Early Warning System (EWS) for Norwegian ports was introduced in 2004 Florø 28 - go to: www.cruise-norway.no Olden/Nordfjord 30 T D Geirangerfjord 32 N Y BU Ålesund 34 NANC : Molde/Åndalsnes 36 OTO PH Kristiansund 38 Narvik 40 Møre and Romsdal Lofoten 42 Vesterålen 44 Y WA R NO Harstad 46 ation Tromsø 48 Presenting V INNO Alta 50 . -

Building a Successful Lighthouse Preservation Society

BUILDING A SUCCESSFUL LIGHTHOUSE PRESERVATION SOCIETY DeTour Reef Light Preservation Society (DRLPS) presented by Jeri Baron Feltner at Keep the Lights On! Strategies for Saving Michigan’s Lighthouses Lighthouse Preservation Workshop Sponsored by the State Historic Preservation Office & The Michigan Lighthouse Project at the Forum of the Michigan Library and Historical Center Lansing, Michigan November 6, 1998 Thank you Michael, it is a pleasure to be here today representing the DeTour Reef Light Preservation Society team at this first historic lighthouse workshop. Part of our team is here today - Carol Melvin our Finance Committee Chairperson, my husband Chuck Feltner our Chief Historian, and Dick Moehl our founder and one of our Directors. Other members are my brother Larry Baron, the video man, Marilyn Fischer, President of the Gulliver Historical Society, Sandy Planisek Director of the GLLM, John Wagner and John Andree. We come here today from the front lines of the creating and operating of a successful lighthouse preservation society. We learned a lot, and I would like to share with you today what we did to earn the honor of being the new caretaker of one of America’s unique resources -- the DeTour Reef Lighthouse. The AGENDA includes: 1) Historical Background 2) The Situation Today 3) DRLPS Purpose 4) Accomplishments 5) Goals 6) The Challenge for the Future 7) Closing Remarks 1) HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Let me give you a brief historical background. The original Lighthouse that is no longer in existence, was the DeTour Point Light established onshore in 1847 and rebuilt in 1861. This Light was replaced DeTour Reef Light Preservation Society - P. -

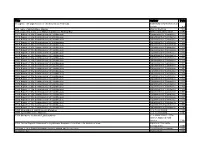

Lighthouse Bibliography.Pdf

Title Author Date 10 Lights: The Lighthouses of the Keweenaw Peninsula Keweenaw County Historical Society n.d. 100 Years of British Glass Making Chance Brothers 1924 137 Steps: The Story of St Mary's Lighthouse Whitley Bay North Tyneside Council 1999 1911 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1911 1912 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1912 1913 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1913 1914 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1914 1915 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1915 1916 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1916 1917 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1917 1918 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1918 1919 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1919 1920 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1920 1921 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1921 1922 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1922 1923 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1923 1924 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1924 1925 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1925 1926 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1926 1927 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1927 1928 Report of the Commissioner of