Bush Chatter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 15 No.2 September 2012 Edition No

The Speedway Researcher Promoting Research into the History of Speedway and Dirt Track Racing Volume 15 No.2 September 2012 Edition No. 58 Lee Richardson The tragic loss of Lee Richardson has had massive coverage in other publications. We would just like to add our sincere condolences to Lee’s wife and children and to his family and friends. Editors Speedway in Australia 1926 In 1926 Lionel Wills visited Australia and his thoughts on speedway in Australia was published in The Motor Cycle on November 25th of that year. We now reproduce that article. “Motor racing,” an Australian daily paper remarked recently, “has definitely become one of the major sports of Sydney.” In Australia, in other words, a motor race meeting often draws as big a crowd as does a football match, and the time is obviously approaching when it will rival horse racing, the Australians’ favourite pastime. Now even with the increasing popularity of the T.T. races, the same cannot be said of England, and it may therefore interest home readers to hear how it is done on the other side of the world. In cinder-track racing Australia has discovered a type of event which is as thrilling as the “T.T.,” and even more spectacular than sand-racing; in addition, it requires a not very great outlay of capital, and the track is easily accessible from the big city. Ten minutes on a tram, fact brings Sydney to the Speedway Royal, which is simply, a broad unbanked cinder track constructed round a football oval. Australian football is played on an oval field, and the track round it is about one-third of a mile, with huge stands all round, having accommodation for thousands of people. -

Fim Speedway European Championship (1952-75) Uem/ Fim-E Speedway European Championship (2001- )

FIM/ UEM/ FIM-E SPEEDWAY EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP FIM SPEEDWAY EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP (1952-75) UEM/ FIM-E SPEEDWAY EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP (2001- ) Year Posn Rider Nationality Bike Points 1952 1. Rune Sörmander (1st) Sweden JAP 2. Olly Nygren Sweden JAP 3. Stig Pramberg Sweden 1953 1. Leif ‘Basse’ Hveem Norway 2. Olly Nygren Sweden JAP 3. Dan Forsberg Sweden 1954 1. Ove Fundin (1st) Sweden JAP 2. Rune Sörmander Sweden JAP 3. Sune Karlsson Sweden 1955 1. Henry Andersen Norway JAP 2. Olly Nygren Sweden JAP 3. Kjell Carlsson Sweden 1956 1. Ove Fundin (2nd) Sweden JAP 2. Per-Olof Söderman Sweden 3. Olle Andersson II Sweden 1957 1. Rune Sörmander (2nd) Sweden JAP 2. Per-Olof Söderman Sweden 3. Josef Hofmeister West Germany JAP 1958 1. Ove Fundin (3rd) Sweden JAP 2. Josef Hofmeister West Germany JAP 3. Rune Sörmander Sweden JAP 1959 1. Ove Fundin (4th) Sweden JAP 2. Josef Hofmeister West Germany JAP 3. Mieczysław Polukard Poland ESO 1960 1. Marian Kaiser Poland ESO 2. Ove Fundin Sweden JAP 3. Stefan Kwoczała Poland ESO 1961 1. Ove Fundin (5th) Sweden JAP 2. Björn Knutsson Sweden JAP 3. Igor Plechanov USSR ESO 1 FIM/ UEM/ FIM-E SPEEDWAY EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP 1962 1. Björn Knutsson (1st) Sweden JAP 2. Ove Fundin Sweden JAP 3. Göte Nordin Sweden JAP 1963 1. Björn Knutsson (2nd) Sweden JAP 2. Ove Fundin Sweden 3. Per-Olof Söderman Sweden 1964 1. Zbigniew Podlecki Poland ESO 2. Björn Knutsson Sweden JAP 3. Boris Samorodov USSR ESO 1965 1. Ove Fundin (6th) Sweden JAP 2. Björn Knutsson Sweden JAP 3. -

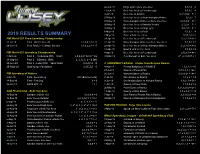

2019 Results Summary

24-Jun-19 Kings Lynn v Belle Vue Aces 0,0,F,0 = 0 13-Jun-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Peterborough 0,0,3,1 = 4 3-Jun-19 Belle Vue vs Ipswich 0,2*,3,0,2 = 7+1 27-May-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Wolverhampton Wolves 3,0,3,1= 7 27-May-19 Wolverhampton Wolves vs Belle Vue Aces 2,2,3,0,2*= 9+1 20-May-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Swindon Robins 2*,2,2,1 = 7+1 16-May-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Kings Lynn 3,2*,3,0 = 8+1 6-May-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Poole 3,R,0,1 = 4 2019 RESULTS SUMMARY 2-May-19 Poole v Belle Vue Aces 1,0,R,1,0 = 2 FIM World U21 Team Speedway Championship 29-Apr-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Peterborough 0,1,2*,0 = 3+1 12-Jul-19 Final - Manchester, UK 2,2,0,4,1,3 = 12 22-Apr-19 Wolverhampton Wolves vs Belle Vue Aces 0,3,0,0 = 3 29-Jun-19 Semi Final 2 - Vetlanda, Sweden 3,1,6,2,2,3 = 17 22-Apr-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Wolverhampton Wolves 2*,2*,0,0 = 4+2 18-Apr-19 Ipswich vs Belle Vue Aces 0,0,0,0 = 4 FIM World U21 Speedway Championship 4-Apr-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Peterborough 2,R,2*,0 = 4+1 4-Oct-19 Final 3 – Pardubice (4th – Final) 1,3,3,3,2=12+3 = 15 31-Mar-19 Peterborough vs Belle Vue Aces 2 *, 2,3,0,0=7 + 1 14-Sep-19 Final 2 – Güstrow (9th) 1, 1, X, 3, 1 = 6 (W) 22-Jun-19 Final 1 - Lubin (4th – Semi Final) 3,0,3,F,2 = 8 2. -

Leicester Lions Season 1978

Leicester Lions Season 1978 Compiled by Dave Allan First published March 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This file was only made possible thanks to the invaluable contributions of the following: Steve Wilkes & Gary Done (Ellesmere Port & 1978 Speedway Mails) Stuart Staite-Aris & associates (Coventry) Mike Hunter (Edinburgh) Brian Collins (Internationals) Mark Aspinell (Rye House) Gary Weldon (Boston) Steve Ashley (Boston & Leicester) John (Hull) Colin Jewes & Phil Johnson (Cradley Heath) Arnie Gibbons (Reading) Mark Fellows (Wolverhampton) Matt Jackson (Sheffield) Neil Fife (Newcastle) David Housely (Various) Keith Corns (Various) The knowledgable members of the British Speedway Forum and the Easy, Tiger! Forum RACECARDS The following symbols are in use throughout this file: R/R Rider replacement N Rider replaced by reserve TS Rider replaced by tactical substitute R Rider did not finish for reason other than fall or exclusion EF Rider suffered engine failure and failed to finish F Rider fell and did not remount FX Rider fell and was excluded from race or rerun FN Rider fell and was unable to take his place in rerun E Rider excluded for starting offence (including tape touching & breaking, delaying start, etc.) M Rider excluded under two minute rule X Rider excluded for any other reason not E or M. Reason for exclusion noted where known. NS Rider failed to start but was not excluded or replaced NTR New track record ETR Equals track record Reruns are not assumed, they are only recorded where reported. (guest) Rider is making a ‘full and proper’ guest -

2008 Manual of Motorcycle Sport

-/4/2#9#,).'Motorcycling Australia !5342!,)! 2008 Manual of Motorcycle Sport Published annually since 1928 Motorcycling Australia is by Motorcycling Australia the Australian affiliate of ABN 83 057 830 083 the Fèdèration Internationale 147 Montague Street de Motocyclisme. South Melbourne 3205 Victoria Australia Tel: 03 9684 0500 Fax: 03 9684 0555 email: [email protected] website: www.ma.org .au This publication is available electronically from: www.ma.org.au www.fim.ch ISSN 1833-2609 2008. All material in this book is the copyright of Motorcycling Australia Ltd (MA) and may not be reproduced without prior written permission from the Chief Executive Officer. enjoy the ride INTRODUCTION TO THE 2008 EDITION Welcome to the 2008 Manual of Motorcycle Sport, a manual designed to assist you in your riding throughout the upcoming calendar year. While the information in the 2008 MoMS is correct at the time of printing, things can – and often do change. For this reason, we urge you to keep an eye on our website (www.ma.org.au) and on our fortnightly e-Newsletters for information about any changes that may occur. We will soon have a designated area of the website especially for the manual, and this area will house any amendments that are related to the printed version. You will also be able to download an on-line version of the manual from this area as well. It is fair to say that 2007 was a truly successful year for motorcycling in Australia – both on the bike and behind the scenes. A feat such as Casey Stoner’s in becoming the next of our home-grown World Champions certainly cannot be overlooked, and we will get into the racing performance feats shortly. -

Lewi Kerr Exclusive the Bike!

LEE KILBY IS JOINING the Eastbourne Lee was also excited to start work Robins’ fans: “Swindon is my club and HG AEROSPACE EAGLES SPEEDWAY MAGAZINE HG Aerospace Eagles management with Eastbourne’s all-British team who, that is where my heart is. I want them team on a season-long loan from he said, connected well with to come back in 2022, of course I do, Swindon. supporters. but for this year I am going to be 100 He will take responsibility for “You sense that from the moment per cent Eastbourne. commercial and community activities you step into Arlington and from a “I am looking to bring some new as well as having oversight of match commercial and promoting initiatives to the club and doing day arrangements. perspective that’s all you can ask for. everything I can to help the progress Eastbourne Speedway director Ian “It builds so many bridges. Once you and have a good year.” Jordan said Lee would be a great can hook a kid and it’s someone they Ian Jordan commented: “I think it's addition to the team during the year can look up to, the kid is hooked. You always important to clarify as clearly as Swindon cannot run while their retain that youngster and he or she possible any questions before they are No. 4 stadium is rebuilt. brings mum and dad with them,” Lee asked in any communication and, Lee is the son of Bob Kilby who was a said. therefore, it's very important for us to legend for the Swindon Robins and “Eastbourne already have a base and tell everyone not only how delighted scored more than 4,000 points for the there are great opportunities to bring we are by this appointment, but to Wiltshire club. -

Justin Sedgmen

Dream Team : Justin Sedgmen My name is Justin Sedgmen. I race junior speedway in Australia. I am a good friend of Leigh Adams. My brother Ryan is Australian u/16 champion. Jason Crump Jason Lyons Jason Crump The two times world champion. He's at number one because of his want to win. Jason if he is last will never stop trying until he gets to that number 1 spot. I was talking to his gran pa in Australia, he said Jason will always keep wining because he has got a gift. When Jason gets on to a speedway bike, he changes. He goes from Jasson Crump to world Champion. The only thing that will stop Jason Crump from wining will be his bikes. Jason Lyons Mr Mildura. That's what they call Jason Lyons when he rides around Olympic Park. If there was a world Final around Mildura he would make the final for sure. He has got un-real talent. Phil Crump Sir Phil Crump, what a freak! Jason Crump is what he is because of this man. The 4 times Australian champion. My Dad told me he is the only person to ride around Mildura with the handle bars over the fence. Tony Rickardsson was not the first person to ride the fence. It got a bit tight so Crumpy said I'll just go on the fence. Mark Lemon This guy is more than a freak. you never know with Lemo, he can go out and beat Leigh Adams and Jason Crump, or he could do really bad. -

2018 Manual of Motorcycle Sport

Motorcycling Australia MOTORCYCLING AUSTRALIA 2018 Manual of Motorcycle Sport Published annually since 1928 Motorcycling Australia is by Motorcycling Australia the Australian affiliate of ABN 83 057 830 083 the Fèdèration Internationale PO Box 134 de Motocyclisme. South Melbourne 3205 Victoria Australia Tel: 03 9684 0500 Fax: 03 9684 0555 email: [email protected] website: www.ma.org.au This publication is available electronically from: www.fim.ch www.ma.org.au ISSN 1833-2609 2018. All material in this book is the copyright of Motorcycling Australia Ltd (MA) and may not be reproduced without prior written permission from the CEO INTRODUCTION 2018 MANUAL OF MOTORCYCLE SPORT INTRODUCTION TO THE 2018 EDITION Welcome to Motorcycling Australia’s 2018 Manual of Motorcycle Sport (MoMS), a publication designed to assist you in your riding or officiating throughout the upcoming calendar year. The Manual of Motorcycle Sport The MoMS is the motorcycle racing ‘Bible’ and the development and provision of the rules and information within this resource is one of the key functions of Motorcycling Australia (MA). While the information is correct at the time of printing, things can and do change throughout the year. For this reason we urge you to keep an eye on the MA website, where bulletins and updated versions are posted as necessary (www.ma.org.au). The PDF version of the manual is optimised for use on all your devices for access to the MoMS anywhere, anytime. You have the option to utilise the manual offline, with content available chapter by chapter to download, save and print as required. -

September 2011 3.5Mb

Free Copy In This Edition: Page Page Charles La Trobe 2 Improving Your Memory 20 Photography 4 The Mobile Phone 21 Point Nepean 6 Victoria’s Gold Rush 22 Melbourne Zoo 8 André Rieu 24 Avalon Raceway 10 Coffee Time! 26 Smurfs 12 Where Is That? 28 Knowing the Road Rules 14 Geelong Word Search 29 Fort Queenscliff 16 Minotaur 30 Novac Djokovic 18 150 Years Ago 31 Sidney Austin 19 Then… & Now 32 Charles Joseph La Trobe was born on March 20, 1801 in London. After receiving his education at schools in London, La Trobe started teaching at Fairfield Boys Boarding School in Manchester. At age 23 he then travelled to Neuchâtel, Switzerland and became tutor to the family of Count Albert de Pourtalès for the next 2 years. He then became a noted mountaineer—a pioneer member of the Alpine Club. In 1832 La Trobe accompanied Count de Pourtales during a tour of America, including sailing down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. He published four books based on his travels around America. Returning to Europe, La Trobe stayed at the country house of Frederic Auguste de Montmollin, a Swiss councilor of state, and there became engaged to one of the Montmollin‟s daughters, Sophie. They were married in the British Legation at Berne on September 16, 1835. Upon completing an assignment in the West Indies for the British Govern- ment, La Trobe was sent to the Port Phillip District as Superintendant, even though he had had little managerial and administrative experience. He arrived in Melbourne on September 30, 1839 with his wife and daughter, two servants and a pre-fabricated house. -

Tommy Jansson Tribute

A Tribute To Tommy Jansson His Race Heat Details For Great Britain Compiled By Wimbledon Speedway Supporter Robert Browne From Official Match Programmes and Speedway Magazines 1970 Young England Vs Young Sweden Division Two Test Series Tour Thursday 23 July (Division Two International - 1st Test Match) (Teeside) Young England 68 Richard May 16, John Louis 15, Dave Jessup 13, Roger Mills 10, Tom Leadbitter 7, Geoff Mahoney 7, Alan Knapkin (res) did not ride, Chris Bailey (res) did not ride Young Sweden 38 Kall Haage 12, Tommy Johansson 11, Tommy Jansson 10, Kurt Nyqvist 2, Goeran Jansson 2, Sixten Karlberg 1, Lennart Michanek 0, Roland Karlsson (res) 0 Heat 2 Louis, Maloney, Nyqvist, T.Jansson 71.0 Heat 11 T.Jansson, Louis, Maloney, Nyqvist 71.0 Heat 5 Mills, Jessup, Nyqvist, T.Jansson 71.6 Heat 14 Jessup, T.Jansson, Mills, Nyqvist 70.4 Heat 8 May, T.Jansson, Leadbitter, Nyqvist 70.8 Heat 16 T.Jansson, May, Leadbitter, Nyqvist 71.4 Friday 24 July (Division Two International - 2nd Test Match) (Workington) Young England 75 Tom Leadbitter 18, Richard May 16, Eric Broadbelt 15, John Louis 10, Dave Jessup 8, Geoff Mahoney 4, Reg Wilson 4 Young Sweden 32 Tommy Johansson 11, Roland Karlsson 6, Kall Haage 5, Goran Jansson 5, Kurt Nyqvist 4, Sixten Karlberg 1, Tommy Jansson 0 Heat 3 (rerun) Leadbitter, Maloney, Nyqvist, T.Jansson (f, exc) 77.0 Tommy Jansson, suffered suspected leg and back injuries, and was taken to hospital. He also he took no further part in the series, due to these injuries. Series Score Young England 4, Young Sweden 0 (1 match -

Scooter News - 2016 Race Calendar

SCOOTER NEWS - 2016 RACE CALENDAR This is a guide only - always check with the organisers before heading out! Date VIC MX/Off Road Club Events State/National Events Other Fun Stuff 1 17/10/2016 SCOOTER NEWS - 2016 RACE CALENDAR This is a guide only - always check with the organisers before heading out! Date VIC MX/Off Road Club Events State/National Events Other Fun Stuff 2 17/10/2016 SCOOTER NEWS - 2016 RACE CALENDAR This is a guide only - always check with the organisers before heading out! Date VIC MX/Off Road Club Events State/National Events Other Fun Stuff OCTOBER OCTOBER OCTOBER 1. 2016 MotoGP Phillip Island, 20- 23 Oct 2. 2016 FIM Speedway Grand Prix 1. Diamond Valley MCC, Club MX Final, Ethihad Stadium Melbourne, includes Pre80 and Pre90 VMX and 22-23 Oct Trail Bike class, Broadford, 23rd Oct 3. Quad Riders of Victoria, Enduro 22-23 2. North West MCC, Working Bee, 23rd Rnd 4, Broadford, 22nd Oct Oct 4. Women's Off-Road Training Day, OCT 3. Alexandra MCC, Dean Watson Stony Creek (Peter Boyle's place), Annual Memorial MX Cup, 23rd SAT 22nd Oct October 5. Black Dog Ride "Milk Run", 4. Rosebud MCC, Club MX, 23rd Oct Bendigo, 23-29th Oct 6. Enduro Trials Cross training course, Macedon Ranges, Trials Experience, 22nd Oct 3 17/10/2016 SCOOTER NEWS - 2016 RACE CALENDAR This is a guide only - always check with the organisers before heading out! Date VIC MX/Off Road Club Events State/National Events Other Fun Stuff 1. VERi Vinduro Castella, 30th Oct 2. -

2016 Manual of Motorcycle Sport

Motorcycling Australia MOTORCYCLING AUSTRALIA 2016 Manual of Motorcycle Sport Published annually since 1928 Motorcycling Australia is by Motorcycling Australia the Australian affiliate of ABN 83 057 830 083 the Fèdèration Internationale PO Box 134 de Motocyclisme. South Melbourne 3205 Victoria Australia Tel: 03 9684 0500 Fax: 03 9684 0555 email: [email protected] website: www.ma.org.au This publication is available electronically from: www.fim.ch www.moms.org.au ISSN 1833-2609 2016. All material in this book is the copyright of Motorcycling Australia Ltd (MA) and may not be reproduced without prior written permission from the CEO INTRODUCTION 2016 MANUAL OF MOTORCYCLE SPORT INTRODUCTION TO THE 2016 EDITION Welcome to Motorcycling Australia’s 2016 Manual of Motorcycle Sport (MoMS), a publication designed to assist you in your riding or officiating throughout the upcoming calendar year. The Manual of Motorcycle Sport The MoMS is the motorcycle racing ‘Bible’ and the development and provision of the rules and information within this resource is one of the key functions of Motorcycling Australia. While the information is correct at the time of printing, things can change. For this reason we urge you to keep an eye on both our website (www.ma.org.au) and our dedicated Manual of Motorcycle Sport site; www.moms.org.au Our fully responsive moms.org.au website is optimised for use on all your devices for access to the MoMS anywhere, anytime. You also have the option to utilise the manual offline, with content available chapter by chapter as a PDF to download, save and print as required.