Essington Hall Training Track

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Borough of Haringey

London Borough of Haringey Contaminated Land Strategy RH Environmental August 2004 LB Haringey Contaminated Land Strategy August 2004 RH Environmental Cwmbychan Rhydlewis Llandysul Ceredigion SA44 5SB T: 01559 363836 E: [email protected] The LB Haringey Contaminated Land Strategy was revised and rewritten between November 2003 and August 2004 by RH Environmental, Environmental Health Consultants. Copyright: London Borough of Haringey 2004 2 LB Haringey Contaminated Land Strategy August 2004 Contents Contents Executive Summary Terms of Reference Management System Structure Contaminated Land Strategy and Management System Manual The Haringey Environment Management System Procedures Appendices 3 LB Haringey Contaminated Land Strategy August 2004 1.0 Executive Summary This Contaminated Land Strategy has been prepared for the Environmental Control Services of the London Borough of Haringey, in accordance with the Environmental Protection Act 1990, (as amended by the Environment Act 1995). Under this legislation the Council is obliged to adopt and implement a contaminated land strategy. The Council is under a statutory duty to secure the remediation of contaminated land where significant harm is being, or could be caused to the environment, human health or to structures. The strategy relates to land contaminated by past activities only. The Council is the primary authority for the implementation of the strategy. It will consult with and take advice from other agencies, for example the Environment Agency, English Nature, English Heritage and the Greater London Authority. The strategy outlines the Councils’ approach to dealing with contaminated land within the borough. Procedures have been developed to identify responsibilities within the Council and to ensure the Council deals with land which is contaminated, in a consistent and diligent manner. -

Boxing, Governance and Western Law

An Outlaw Practice: Boxing, Governance and Western Law Ian J*M. Warren A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Human Movement, Performance and Recreation Victoria University 2005 FTS THESIS 344.099 WAR 30001008090740 Warren, Ian J. M An outlaw practice : boxing, governance and western law Abstract This investigation examines the uses of Western law to regulate and at times outlaw the sport of boxing. Drawing on a primary sample of two hundred and one reported judicial decisions canvassing the breadth of recognised legal categories, and an allied range fight lore supporting, opposing or critically reviewing the sport's development since the beginning of the nineteenth century, discernible evolutionary trends in Western law, language and modern sport are identified. Emphasis is placed on prominent intersections between public and private legal rules, their enforcement, paternalism and various evolutionary developments in fight culture in recorded English, New Zealand, United States, Australian and Canadian sources. Fower, governance and regulation are explored alongside pertinent ethical, literary and medical debates spanning two hundred years of Western boxing history. & Acknowledgements and Declaration This has been a very solitary endeavour. Thanks are extended to: The School of HMFR and the PGRU @ VU for complete support throughout; Tanuny Gurvits for her sharing final submission angst: best of sporting luck; Feter Mewett, Bob Petersen, Dr Danielle Tyson & Dr Steve Tudor; -

Volume 15 No.2 September 2012 Edition No

The Speedway Researcher Promoting Research into the History of Speedway and Dirt Track Racing Volume 15 No.2 September 2012 Edition No. 58 Lee Richardson The tragic loss of Lee Richardson has had massive coverage in other publications. We would just like to add our sincere condolences to Lee’s wife and children and to his family and friends. Editors Speedway in Australia 1926 In 1926 Lionel Wills visited Australia and his thoughts on speedway in Australia was published in The Motor Cycle on November 25th of that year. We now reproduce that article. “Motor racing,” an Australian daily paper remarked recently, “has definitely become one of the major sports of Sydney.” In Australia, in other words, a motor race meeting often draws as big a crowd as does a football match, and the time is obviously approaching when it will rival horse racing, the Australians’ favourite pastime. Now even with the increasing popularity of the T.T. races, the same cannot be said of England, and it may therefore interest home readers to hear how it is done on the other side of the world. In cinder-track racing Australia has discovered a type of event which is as thrilling as the “T.T.,” and even more spectacular than sand-racing; in addition, it requires a not very great outlay of capital, and the track is easily accessible from the big city. Ten minutes on a tram, fact brings Sydney to the Speedway Royal, which is simply, a broad unbanked cinder track constructed round a football oval. Australian football is played on an oval field, and the track round it is about one-third of a mile, with huge stands all round, having accommodation for thousands of people. -

Belle Vue 1948

Belle Vue 1948 Compiled by Jim Henry and Barry Stephenson Update 31.5.2014 Updated 6.8.2020 Saturday 27th March 1948 Belle Vue Stadium, Manchester Manchester Cup Jack Parker E 3 3 3 9 Dent Oliver 1 0 2 E 3 Bill Pitcher F 2 3 5 Brian Wilson 3 2 F 1 6 Bob Fletcher F 0 Ralph Horne 2 1 1 1 5 Jim Boyd 2 2 2 E 6 Wally Lloyd 1 E 2 2 5 Louis Lawson F 1 1 3 5 Walter Hull 3 1 1 0 5 Bert Lacey E 0 0 1 1 Jack Tennant 1 0 0 1 2 Tommy Price 3 3 3 3 12 Bill Gilbert 3 2 2 1 8 George Wilks 2 3 3 3 11 Split Waterman F 0 E 2 2 Roy Craighead 2 3 2 2 9 Ht1 T.Price, Wilks, Oliver, Parker (ef) 77.0 Ht2 Wilson, Boyd, Pitcher (f), Lawson (f) 79.8 Ht3 Hull, Horne, Fletcher (f), Lacey (ef) 75.6 Ht4 Gilbert, Craighead, Lloyd, Waterman (f) 78.0 Ht5 Wilks, Boyd, Hull, Waterman 77.8 Ht6 Parker, Pitcher, Tennant, Lloyd (ef) 78.8 Ht7 Price, Gilbert, Lawson, Lacey 77.2 Ht8 Craighead, Wilson, Horne, Oliver 79.2 Ht9 Wilks, Gilbert, Horne, Tennant 78.0 Ht10 Parker, Boyd, Gilbert, Lacey 79.8 Ht11 Wilks, Craighead, Lawson, Tennant 79.8 Ht12 Lawson, Oliver, Hull, Waterman (ef) 81.0 Ht13 Price, Lloyd, Tennant, Wilson (f) 80.4 Ht14 Parker, Craighead, Wilson, Hull 77.8 Ht15 Price, Waterman, Horne, Boyd (ef) 79.4 Ht16 Pitcher, Lloyd, Lacey, Oliver (ef) 80.4 Final Parker, Wilks, Price, Craighead 80.0 Novice Race Alec Edwards, Jack Gordon, Ken Sharples, George Smith (ret) 88.2 Stadium Scratch Races Ht1 Lawson, Gilbert, Lloyd, Pitcher 80.0 Ht2 Lacey, Tennant, Horne (nf), Boyd (nf) 84.2 Monday 29th March 1948 Belle Vue Stadium, Manchester Easter Tournament (Afternoon) Jack Parker 3 -

Fim Speedway European Championship (1952-75) Uem/ Fim-E Speedway European Championship (2001- )

FIM/ UEM/ FIM-E SPEEDWAY EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP FIM SPEEDWAY EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP (1952-75) UEM/ FIM-E SPEEDWAY EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP (2001- ) Year Posn Rider Nationality Bike Points 1952 1. Rune Sörmander (1st) Sweden JAP 2. Olly Nygren Sweden JAP 3. Stig Pramberg Sweden 1953 1. Leif ‘Basse’ Hveem Norway 2. Olly Nygren Sweden JAP 3. Dan Forsberg Sweden 1954 1. Ove Fundin (1st) Sweden JAP 2. Rune Sörmander Sweden JAP 3. Sune Karlsson Sweden 1955 1. Henry Andersen Norway JAP 2. Olly Nygren Sweden JAP 3. Kjell Carlsson Sweden 1956 1. Ove Fundin (2nd) Sweden JAP 2. Per-Olof Söderman Sweden 3. Olle Andersson II Sweden 1957 1. Rune Sörmander (2nd) Sweden JAP 2. Per-Olof Söderman Sweden 3. Josef Hofmeister West Germany JAP 1958 1. Ove Fundin (3rd) Sweden JAP 2. Josef Hofmeister West Germany JAP 3. Rune Sörmander Sweden JAP 1959 1. Ove Fundin (4th) Sweden JAP 2. Josef Hofmeister West Germany JAP 3. Mieczysław Polukard Poland ESO 1960 1. Marian Kaiser Poland ESO 2. Ove Fundin Sweden JAP 3. Stefan Kwoczała Poland ESO 1961 1. Ove Fundin (5th) Sweden JAP 2. Björn Knutsson Sweden JAP 3. Igor Plechanov USSR ESO 1 FIM/ UEM/ FIM-E SPEEDWAY EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP 1962 1. Björn Knutsson (1st) Sweden JAP 2. Ove Fundin Sweden JAP 3. Göte Nordin Sweden JAP 1963 1. Björn Knutsson (2nd) Sweden JAP 2. Ove Fundin Sweden 3. Per-Olof Söderman Sweden 1964 1. Zbigniew Podlecki Poland ESO 2. Björn Knutsson Sweden JAP 3. Boris Samorodov USSR ESO 1965 1. Ove Fundin (6th) Sweden JAP 2. Björn Knutsson Sweden JAP 3. -

Julius Totalisator

ENGINEERS AUSTRALIA ENGINEERING HERITAGE QUEENSLAND NOMINATION ENGINEERING HERITAGE AUSTRALIA HERITAGE RECOGNITION PROGRAM JULIUS TOTALISATOR SEPTEMBER 2014 1 FRONT COVER PHOTOGRAPH CAPTION The world’s first operational computer preassembled at the Sydney Factory in 1913, prior to its installation at Ellerslie, Auckland, New Zealand. Photographer unknown. Collection – Powerhouse Museum, Sydney “….although it looked like a giant tangle of piano wires, pulleys and cast iron boxes and many racing officials predicted that it would not work, it was a great success.” Brian Conlon – Totalisator History – Automatic Totalisator Ltd – later ATL Submitted by: Engineering Heritage Queensland Panel Prepared for E.H.Q. by Panel Member Paul D. Coghlan With major information supplied by: Brian Conlon (Retired – Ex Chief Engineer of the PDP11 computer totes that superseded this and other Julius totes in Brisbane 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Page 3 Basic Data Page 4 Introduction/History Page 5 & 6 Assessment of Significance Historic Phase/Historic Association Page 7 Creative and Technical Achievement/Research Potential Page 8 Social Relevance/Rarity Representatives/Integrity/Intactness Page 9 Statement of Significance Page 10 Photo Description – 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Page 10 Photos 1, 2, 3 Page 11 Photos 4, 5 Page 12 Photos 6, 7 Page 13 Appendices/Acknowledgement Page 14 Proposed Interpretation Panel Pages 15 -16 Appendix I “The Rutherford Journal” Pages 17-29 Appendix 11 “Totalisators – First Automatic Totalisator” Pages 30- 47 Appendix III “A description of the Julius Totalisator in the Pages 48-55 Eagle Farm Museum” Appendix IV “Brief description Eagle Farm Julius Tote” Pages 56-76 Appendix V “Automatic Totalisators Ltd. -

Map Illustration ©Jane Smith Community Gardens | Laundries Harringay Stadium Photo: from ©English Heritage

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 12 11 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 44 43 39 40 41 42 45 46 47 50 51 48 49 52 53 1. Turnpike Lane station 29. Laurels Healthy Living Centre 2. Lord Ted Willis, author, No. 55 30. St Ann’s Police Station 1871 childhood home 31. St Ann’s Model Cottages built 1858 3. WW1 War Memorial 32. ‘Ghost’ railway bridge from defunct 4. Myristis local treasure since 1960s Palace Gates Railway 5. 1879 School Board Offices 33. Sheik Nazim Mosque was built 6. Spot the dragon on the roof St Mary’s Priory 1871. Iron crosses 7. Forsters Cottages 1860 Almshouses in graveyard behind 8. Tottenham Bus Garage, 1913 34. Rose Cottages, 1825. Now Reid’s 9. Bernie Grant Centre, was Pianos was a builder specialising in Tottenham Baths cold stores 10. St Eloy’s Well giving spring water 35. Shops where the baker’s doubled for over 400 years up as the post office 11. High Cross started off as a 36. Sid the Snail appeared during the wooden cross Queen’s Silver Jubilee 1977 12. Tottenham Town Hall built 1905 37. Woodbury Tavern 1881 13. Austro-Bavarian Lager Beer 38. Triangle Childrens’ Centre Brewery & Ice Factory, 1882 39. TeeToTum Club – working mens’ 14. 247a - Georgian House Sports Club in C19 15. J E Green’s Builders Merchants 40. St Ignatius Church family business for 80 years 41. -

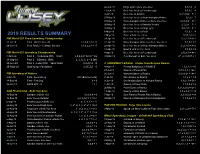

2019 Results Summary

24-Jun-19 Kings Lynn v Belle Vue Aces 0,0,F,0 = 0 13-Jun-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Peterborough 0,0,3,1 = 4 3-Jun-19 Belle Vue vs Ipswich 0,2*,3,0,2 = 7+1 27-May-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Wolverhampton Wolves 3,0,3,1= 7 27-May-19 Wolverhampton Wolves vs Belle Vue Aces 2,2,3,0,2*= 9+1 20-May-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Swindon Robins 2*,2,2,1 = 7+1 16-May-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Kings Lynn 3,2*,3,0 = 8+1 6-May-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Poole 3,R,0,1 = 4 2019 RESULTS SUMMARY 2-May-19 Poole v Belle Vue Aces 1,0,R,1,0 = 2 FIM World U21 Team Speedway Championship 29-Apr-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Peterborough 0,1,2*,0 = 3+1 12-Jul-19 Final - Manchester, UK 2,2,0,4,1,3 = 12 22-Apr-19 Wolverhampton Wolves vs Belle Vue Aces 0,3,0,0 = 3 29-Jun-19 Semi Final 2 - Vetlanda, Sweden 3,1,6,2,2,3 = 17 22-Apr-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Wolverhampton Wolves 2*,2*,0,0 = 4+2 18-Apr-19 Ipswich vs Belle Vue Aces 0,0,0,0 = 4 FIM World U21 Speedway Championship 4-Apr-19 Belle Vue Aces vs Peterborough 2,R,2*,0 = 4+1 4-Oct-19 Final 3 – Pardubice (4th – Final) 1,3,3,3,2=12+3 = 15 31-Mar-19 Peterborough vs Belle Vue Aces 2 *, 2,3,0,0=7 + 1 14-Sep-19 Final 2 – Güstrow (9th) 1, 1, X, 3, 1 = 6 (W) 22-Jun-19 Final 1 - Lubin (4th – Semi Final) 3,0,3,F,2 = 8 2. -

Leicester Lions Season 1978

Leicester Lions Season 1978 Compiled by Dave Allan First published March 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This file was only made possible thanks to the invaluable contributions of the following: Steve Wilkes & Gary Done (Ellesmere Port & 1978 Speedway Mails) Stuart Staite-Aris & associates (Coventry) Mike Hunter (Edinburgh) Brian Collins (Internationals) Mark Aspinell (Rye House) Gary Weldon (Boston) Steve Ashley (Boston & Leicester) John (Hull) Colin Jewes & Phil Johnson (Cradley Heath) Arnie Gibbons (Reading) Mark Fellows (Wolverhampton) Matt Jackson (Sheffield) Neil Fife (Newcastle) David Housely (Various) Keith Corns (Various) The knowledgable members of the British Speedway Forum and the Easy, Tiger! Forum RACECARDS The following symbols are in use throughout this file: R/R Rider replacement N Rider replaced by reserve TS Rider replaced by tactical substitute R Rider did not finish for reason other than fall or exclusion EF Rider suffered engine failure and failed to finish F Rider fell and did not remount FX Rider fell and was excluded from race or rerun FN Rider fell and was unable to take his place in rerun E Rider excluded for starting offence (including tape touching & breaking, delaying start, etc.) M Rider excluded under two minute rule X Rider excluded for any other reason not E or M. Reason for exclusion noted where known. NS Rider failed to start but was not excluded or replaced NTR New track record ETR Equals track record Reruns are not assumed, they are only recorded where reported. (guest) Rider is making a ‘full and proper’ guest -

2008 Manual of Motorcycle Sport

-/4/2#9#,).'Motorcycling Australia !5342!,)! 2008 Manual of Motorcycle Sport Published annually since 1928 Motorcycling Australia is by Motorcycling Australia the Australian affiliate of ABN 83 057 830 083 the Fèdèration Internationale 147 Montague Street de Motocyclisme. South Melbourne 3205 Victoria Australia Tel: 03 9684 0500 Fax: 03 9684 0555 email: [email protected] website: www.ma.org .au This publication is available electronically from: www.ma.org.au www.fim.ch ISSN 1833-2609 2008. All material in this book is the copyright of Motorcycling Australia Ltd (MA) and may not be reproduced without prior written permission from the Chief Executive Officer. enjoy the ride INTRODUCTION TO THE 2008 EDITION Welcome to the 2008 Manual of Motorcycle Sport, a manual designed to assist you in your riding throughout the upcoming calendar year. While the information in the 2008 MoMS is correct at the time of printing, things can – and often do change. For this reason, we urge you to keep an eye on our website (www.ma.org.au) and on our fortnightly e-Newsletters for information about any changes that may occur. We will soon have a designated area of the website especially for the manual, and this area will house any amendments that are related to the printed version. You will also be able to download an on-line version of the manual from this area as well. It is fair to say that 2007 was a truly successful year for motorcycling in Australia – both on the bike and behind the scenes. A feat such as Casey Stoner’s in becoming the next of our home-grown World Champions certainly cannot be overlooked, and we will get into the racing performance feats shortly. -

Lewi Kerr Exclusive the Bike!

LEE KILBY IS JOINING the Eastbourne Lee was also excited to start work Robins’ fans: “Swindon is my club and HG AEROSPACE EAGLES SPEEDWAY MAGAZINE HG Aerospace Eagles management with Eastbourne’s all-British team who, that is where my heart is. I want them team on a season-long loan from he said, connected well with to come back in 2022, of course I do, Swindon. supporters. but for this year I am going to be 100 He will take responsibility for “You sense that from the moment per cent Eastbourne. commercial and community activities you step into Arlington and from a “I am looking to bring some new as well as having oversight of match commercial and promoting initiatives to the club and doing day arrangements. perspective that’s all you can ask for. everything I can to help the progress Eastbourne Speedway director Ian “It builds so many bridges. Once you and have a good year.” Jordan said Lee would be a great can hook a kid and it’s someone they Ian Jordan commented: “I think it's addition to the team during the year can look up to, the kid is hooked. You always important to clarify as clearly as Swindon cannot run while their retain that youngster and he or she possible any questions before they are No. 4 stadium is rebuilt. brings mum and dad with them,” Lee asked in any communication and, Lee is the son of Bob Kilby who was a said. therefore, it's very important for us to legend for the Swindon Robins and “Eastbourne already have a base and tell everyone not only how delighted scored more than 4,000 points for the there are great opportunities to bring we are by this appointment, but to Wiltshire club. -

Justin Sedgmen

Dream Team : Justin Sedgmen My name is Justin Sedgmen. I race junior speedway in Australia. I am a good friend of Leigh Adams. My brother Ryan is Australian u/16 champion. Jason Crump Jason Lyons Jason Crump The two times world champion. He's at number one because of his want to win. Jason if he is last will never stop trying until he gets to that number 1 spot. I was talking to his gran pa in Australia, he said Jason will always keep wining because he has got a gift. When Jason gets on to a speedway bike, he changes. He goes from Jasson Crump to world Champion. The only thing that will stop Jason Crump from wining will be his bikes. Jason Lyons Mr Mildura. That's what they call Jason Lyons when he rides around Olympic Park. If there was a world Final around Mildura he would make the final for sure. He has got un-real talent. Phil Crump Sir Phil Crump, what a freak! Jason Crump is what he is because of this man. The 4 times Australian champion. My Dad told me he is the only person to ride around Mildura with the handle bars over the fence. Tony Rickardsson was not the first person to ride the fence. It got a bit tight so Crumpy said I'll just go on the fence. Mark Lemon This guy is more than a freak. you never know with Lemo, he can go out and beat Leigh Adams and Jason Crump, or he could do really bad.