Mock AAVE on Social Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sonic Necessity-Exarchos

Sonic Necessity and Compositional Invention in #BluesHop: Composing the Blues for Sample-Based Hip Hop Abstract Rap, the musical element of Hip-Hop culture, has depended upon the recorded past to shape its birth, present and, potentially, its future. Founded upon a sample-based methodology, the style’s perceived authenticity and sonic impact are largely attributed to the use of phonographic records, and the unique conditions offered by composition within a sampling context. Yet, while the dependence on pre-existing recordings challenges traditional notions of authorship, it also results in unavoidable legal and financial implications for sampling composers who, increasingly, seek alternative ways to infuse the sample-based method with authentic content. But what are the challenges inherent in attempting to compose new material—inspired by traditional forms—while adhering to Rap’s unique sonic rationale, aesthetics and methodology? How does composing within a stylistic frame rooted in the past (i.e. the Blues) differ under the pursuit of contemporary sonics and methodological preferences (i.e. Hip-Hop’s sample-based process)? And what are the dynamics of this inter-stylistic synthesis? The article argues that in pursuing specific, stylistically determined sonic objectives, sample-based production facilitates an interactive typology of unique conditions for the composition, appropriation, and divergence of traditional musical forms, incubating era-defying genres that leverage the dynamics of this interaction. The musicological inquiry utilizes (auto)ethnography reflecting on professional creative practice, in order to investigate compositional problematics specific to the applied Blues-Hop context, theorize on the nature of inter- stylistic composition, and consider the effects of electronic mediation on genre transformation and stylistic morphing. -

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: a Content Analysis

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Manriquez, Candace Lynn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:10:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624121 THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN IN RAP VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Candace L. Manriquez ____________________________ Copyright © Candace L. Manriquez 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Running head: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman: A Content Analysis prepared by Candace Manriquez has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Lil Wayne Tha Block Is Hot Mp3, Flac, Wma

Lil Wayne Tha Block Is Hot mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Tha Block Is Hot Country: US Released: 1999 Style: Thug Rap MP3 version RAR size: 1683 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1190 mb WMA version RAR size: 1317 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 138 Other Formats: MPC VOX AA DTS WAV RA MP4 Tracklist Hide Credits Intro 1 1:47 Featuring – Big Tymers 2 Tha Block Is Hot 4:12 Loud Pipes 3 5:14 Featuring – B.G., Big Tymers, Juvenile 4 Whatcha Wanna Do 3:50 Kisha 5 4:17 Featuring – The Hot Boys* High Beamin' 6 4:09 Featuring – B.G. 7 Lights Off 4:06 8 F*** Tha World 4:46 Remember Me 9 3:53 Featuring – B.G. Respect Us 10 5:01 Featuring – Juvenile Drop It Like It's Hot 11 5:23 Featuring – B.G., Mannie Fresh Young Playa 12 3:47 Featuring – Big Tymers Enemy Turf 13 4:19 Featuring – Juvenile Not Like Me 14 4:03 Featuring – Big TymersFeaturing [Uncredited] – Papa Reu Come On 15 3:35 Featuring – B.G. 16 Up To Me 4:31 You Want War 17 3:25 Featuring – Turk Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Cash Money Records, Inc. Copyright (c) – Cash Money Records, Inc. Published By – Money Mack Music Manufactured By – Universal Records Inc. Marketed By – Universal Records Inc. Distributed By – Universal Music & Video Distribution, Inc. Made By – PMDC, USA Recorded At – Cash Money Studios Mixed At – Cash Money Studios Mastered At – The Hit Factory Credits A&R [A&R Assistant] – Elaine Lee A&R [A&R Direction] – Dino Delvaille Artwork [Uncredited] – Pen & Pixel Graphics Bass [Lead] – ''Rick The Man''* Coordinator [Production Coordinator] – Sugar -

The United Eras of Hip-Hop (1984-2008)

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer The United Eras of Hip-Hop tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas Examining the perception of hip-hop over the last quarter century dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx 5/1/2009 cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqLawrence Murray wertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw The United Eras of Hip-Hop ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are so many people I need to acknowledge. Dr. Kelton Edmonds was my advisor for this project and I appreciate him helping me to study hip- hop. Dr. Susan Jasko was my advisor at California University of Pennsylvania since 2005 and encouraged me to stay in the Honors Program. Dr. Drew McGukin had the initiative to bring me to the Honors Program in the first place. I wanted to acknowledge everybody in the Honors Department (Dr. Ed Chute, Dr. Erin Mountz, Mrs. Kim Orslene, and Dr. Don Lawson). Doing a Red Hot Chili Peppers project in 2008 for Mr. Max Gonano was also very important. I would be remiss if I left out the encouragement of my family and my friends, who kept assuring me things would work out when I was never certain. Hip-Hop: 2009 Page 1 The United Eras of Hip-Hop TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

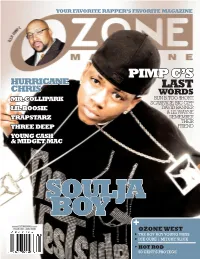

PIMP C’S HURRICANE LAST CHRIS WORDS MR

OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE PIMP C’S HURRICANE LAST CHRIS WORDS MR. COLLIPARK BUN B, TOO $HORT, SCARFACE, BIG GIPP LIL BOOSIE DAVID BANNER & LIL WAYNE REMEMBER TRILL N*GGAS DON’T DIE DON’T N*GGAS TRILL TRAPSTARZ THEIR THREE DEEP FRIEND YOUNG CASH & MIDGET MAC SOULJA BOY +OZONE WEST THE BOY BOY YOUNG MESS JANUARY 2008 ICE CUBE | MITCHY SLICK HOT ROD 50 CENT’S PROTEGE OZONE MAG // YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE PIMP C’S LAST WORDS SOULJA BUN B BOY TOO $HORT CRANKIN’ IT SCARFACE ALL THE WAY BIG GIPP TO THE BANK WITH DAVID BANNER MR. COLLIPARK LIL WAYNE FONSWORTH LIL BOOSIE’S BENTLEY JEWELRY CORY MO 8BALL & FASCINATION MORE TRAPSTARZ SHARE THEIR THREE DEEP FAVORITE MEMORIES OF THE YOUNG CASH SOUTH’S & MIDGET MAC FINEST HURRICANE CHRIS +OZONE WEST THE BOY BOY YOUNG MESS ICE CUBE | MITCHY SLICK HOT ROD 50 CENT’S PROTEGE 8 // OZONE WEST 2 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 8 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 0 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden features ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson 54-59 YEAR END AWARDS PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul 76-79 REMEMBERING PIMP C MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad Sr. 22-23 RAPPERS’ NEW YEARS RESOLUTIONS LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. 74 DIRTY THIRTY: PIMP C’S GREATEST HITS SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Adero Dawson ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Bogan, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, Cierra Middlebrooks, Destine Cajuste, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, K.G. -

Chris Taylor Rice University Hip Hop Parody As Veiled Critique

Chris Taylor Rice University Hip Hop Parody as Veiled Critique 1 Introduction Inherently intertextual, parodies involve the use of semiotic practices indexically associated with the subject of parody, in some cases a particular person or socially- recognizable personae.1 Parodists employ these indexically-linked semiotic practices in an exaggerated fashion, to ridicule indirectly the parodied subject. In the domain of hip hop cultural production, artists marginalized by institutionally-sanctioned systems of distribution use parody to interrogate the naturalness or desirability of prevailing norms which tie semiotic practices to characterological qualities. These parodies involve recognizing norms shared in dissonance, norms regarding authenticity and indigeneity, essentializing discourses which render adherents to opposing norms deviant. Though in this sense discursive formations such as authenticity constrain social action, it is through recognizing and interrogating the normativity of such discourses that social actors – in the case examined here a small population of MCs from Houston, Texas – exercise some measure of agency (Butler 2004, Carter 2007), portraying those who police dominant norms negatively, as less skillful, materialistic, and disingenuously sociopathic. Hip hop parodists achieve this social end by leveling a veiled critique at popular artists. To succeed in their critique, these MCs exploit prior texts (i.e. songs) by transposing strategies popular artists use in styling their personae. For example, in order to communicate a sense of rootedness in a particular neighborhood,2 hip hop artists often employ what I term metastylistic discourse, that is, speech about style. By referring to contextually-bound stylistic practices such as “getting smoked out” and “jammin Screw”3 in the ’hood with their friends, artists establish a connection to place indexically, evoking subterranean, characterological qualities associated with lived experiences of their neighborhoods. -

No Bitin' Allowed a Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All Of

20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 Texas Intellectual Property Law Journal Fall, 2011 Article NO BITIN’ ALLOWED: A HIP-HOP COPYING PARADIGM FOR ALL OF US Horace E. Anderson, Jr.a1 Copyright (c) 2011 Intellectual Property Law Section of the State Bar of Texas; Horace E. Anderson, Jr. I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act’s Regulation of Copying 119 II. Impact of Technology 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm 131 A. Structure 131 1. Biting 131 2. Beat Jacking 133 3. Ghosting 135 4. Quoting 136 5. Sampling 139 B. The Trademark Connection 140 C. The Authors’ Rights Connection 142 D. The New Style - What the Future of Copyright Could Look Like 143 V. Conclusion 143 VI. Appendix A 145 VII. Appendix B 157 VIII. Appendix C 163 *116 Introduction I’m not a biter, I’m a writer for myself and others. I say a B.I.G. verse, I’m only biggin’ up my brother1 It is long past time to reform the Copyright Act. The law of copyright in the United States is at one of its periodic inflection points. In the past, major technological change and major shifts in the way copyrightable works were used have rightly led to major changes in the law. The invention of the printing press prompted the first codification of copyright. The popularity of the player piano contributed to a reevaluation of how musical works should be protected.2 The dawn of the computer age led to an explicit expansion of copyrightable subject matter to include computer programs.3 These are but a few examples of past inflection points; the current one demands a similar level of change. -

Fly - Swag Surfin Free Mp3 Download Swag Surfing Mp3

fly - swag surfin free mp3 download Swag Surfing Mp3. We have collected a lot of useful information about Swag Surfing Mp3 . The links below you will find everything there is to know about Swag Surfing Mp3 on the Internet. Also on our site you will find a lot of other information about kitesurfing, wakeboarding, SUP and the like. Swag Surfin' (Explicit) - YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kf5QZ-WUGKo Jul 29, 2018 · Provided to YouTube by Universal Music Group Swag Surfin' (Explicit) · F.L.Y. (Fast Life Yungstaz) Jamboree ℗ 2009 The Island Def Jam Music Group Released on: 2009-01-01 Producer: Kevin "KE on . Author: FLYISDALIMIT. FLY – Swag Surfin Free Mp3 Download & Listen Online MP3GOO. https://imp3goo.co/download/fly-swag-surfin/ Free Download FLY – Swag Surfin Mp3. We have 20 mp3 files ready to listen and download. To start the download you need to click on the [Download] button. We recommend the first song named FLY - Swag Surfin HQ.mp3 with a quality of 320 kbps. F.L.Y. - Swag Surfin' [Prod. By K.E. On The Track] mp3 . https://www.livemixtapes.com/download/mp3/202862/fly_swag_surfin_prod_by_ke_on_the_track.html F.L.Y. Swag Surfin' [Prod. By K.E. On The Track] free mp3 download and stream. Swag Surfin - Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swag_Surfin "Swag Surfin" is the debut single by American hip hop group Fast Life Yungstaz. It is featured on their debut album Jamboree and is produced by K.E. on the Track.. It is the unofficial anthem of the WNBA's Washington Mystics and was played at the game in which the team won its first championship.Genre: Trap, pop rap. -

Pimp C Greatest Hits Zip 15

1 / 5 Pimp C Greatest Hits Zip 15 CD Albums with the greatest sales gains this week. •Recording Industry Assn. Of America (RIM) certification for net shipment of 500,000 album units (Gold). ... State, Zip E-mail Please note: Orders are payable in U.S. funds drawn on a U.S. ... 50 44 15 B.G. • CASH MONEY 860909/UNIVERSAL (11.98/17.98) CHECKMATE 5 .... Aug 7, 2007 — [Intro: Pimp C (screwed)] Know what I'm ... I keep a whole zip (Whole zip), a whole clip (A whole clip) In case these ... Swinging big-bodies. Swishers and ... This is UGK, get it? Bun and ... Trill Niggaz Don't Die. 14. How Long Can It Last. 15. Still Ridin' Dirty. 16. ... Underground Kingz [Tracklist + Album Art].. DOWNLOAD ALBUM: UGK - Ridin' Dirty Zip & Mp3 | HIPHOPDE. Xay The DJ - Best Of UGK-2020 : Free Download, Borrow, and ... Bun B & Talib Kweli playing .... Aug 13, 2020 — Z r0 z ro greatest hits chopped n screwed hosted by dj killa tex ... by Z-Ro on Napster Download full album Z-Ro - Sadism (2018) . pimp c .. Autoblog brings you car news; expert reviews of cars, trucks, crossovers and SUVs; and pictures and video. Research and compare vehicles, find local dealers, .... Preview the embedded widget. First off, the tracks I picked were some of my favorite tracks from UGK. P!nk – Raise Your Glass. Pimp C Greatest Hits Zip 15 -- .... Jun 4, 2019 — The second track off James Blake's feature-heavy Assume Form hits you ... the biggest pop star on the planet, and they're beautifully devastating.