Housing Activism Initiatives and Land-Use Conflicts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Halele Carol, Bucharest Observatory Case

8. Halele Carol (Bucharest, Romania) This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 776766 Space for Logos H2020 PROJECT Grant Agreement No 776766 Organizing, Promoting and Enabling Heritage Re- Project Full Title use through Inclusion, Technology, Access, Governance and Empowerment Project Acronym OpenHeritage Grant Agreement No. 776766 Coordinator Metropolitan Research Institute (MRI) Project duration June 2018 – May 2021 (48 months) Project website www.openheritage.eu Work Package No. 2 Deliverable D2.2 Individual report on the Observatory Cases Delivery Date 30.11.2019 Author(s) Alina, Tomescu (Eurodite) Joep, de Roo; Meta, van Drunen; Cristiana, Stoian; Contributor(s) (Eurodite); Constantin, Goagea (Zeppelin); Reviewer(s) (if applicable) Public (PU) X Dissemination level: Confidential, only for members of the consortium (CO) This document has been prepared in the framework of the European project OpenHeritage – Organizing, Promoting and Enabling Heritage Re-use through Inclusion, Technology, Access, Governance and Empowerment. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 776766. The sole responsibility for the content of this document lies with the authors. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the European Union. Neither the EASME nor the European Commission is responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. Deliverable -

1 UNIVERSITY of ARTS in BELGRADE Interdisciplinary

UNIVERSITY OF ARTS IN BELGRADE Interdisciplinary postgraduate studies Cultural management and cultural policy Master thesis Reinventing the City: Outlook on Bucharest's Cultural Policy By: Bianca Floarea Supervisor: Milena Dragićević-Šešić, PhD Belgrade, October 2007 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………… ..………. 3 Abstract……………. …………………………..………………….…………………………..……... 4 Introduction.…………………………………….………………………………………………...…... 5 Methodological Approach. Research Design and Data Analysis….………………………..…….. 7 I. The Evolution of Urban Cultural Policies in Europe..……………………….…............................. 9 I.1. Cultural Policies and the City…………………………………………….…… 9 I.2. Historical Trajectory of Urban Cultural Policies……………………………… 11 II. The Cultural Policy of Bucharest. Analysis and Diagnosis of the City Government’s Approach to Culture……………………………………………………………………………………………... 26 II.1. The City: History, Demographics, Economical Indicators, Architecture and the Arts... 26 II.1.1. History……………………………………………………………………… 27 II.1.2. Demographics………………………………………………………….…… 29 II.1.3. Economical Indicators……………………………………………………… 30 II.1.4. Architecture………………………………………………………………… 30 II.1.5. The Arts Scene…………………………………..…………………………. 32 II. 2. The Local Government: History, Functioning and Structure. Overview of the Cultural Administration………………………………………………………………. 34 II.2.1. The Local Government: History, Functioning And Structure…….……..… 34 II.2.2. Overview of the Cultural Administration…………………..……………… 37 II.3 The Official Approach to Culture -

A Delegation from the Congress Observed the Local and Regional Elections in Romania on the 6 June 2004

THE CONGRESS OF LOCAL AND REGIONAL AUTHORITIES Council of Europe F – 67075 Strasbourg Cedex Tel : +33 (0)3 88 41 20 00 Fax : +33 (0)3 88 41 27 51/ 37 47 http://www.coe.int/cplre THE BUREAU OF THE CONGRESS CG/BUR (11) 25 Strasbourg, 16 July 2004 REPORT ON THE OBSERVATION OF LOCAL AND REGIONAL ELECTIONS IN ROMANIA (6 June 2004) President of the Delegation : Günther Krug (Germany, R, SOC) __________ Document adopted by the Bureau of the Congress on 12 July 2004 2 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3 1. View of the Delegation ............................................................................................................... 4 2. Background................................................................................................................................. 4 3. Invitation ..................................................................................................................................... 4 4. Delegation ................................................................................................................................... 5 5. Background Information for the Delegation ........................................................................... 5 a. A Report on Local Democracy in Romania ................................................................................. 5 b. An Information Report on Local and Regional Democracy in Romania in 2002 ...................... -

Diana Culescu

Curriculum vitae Europass Informații personale Nume / Prenume CULESCU Diana-Lavinia Adresă Str. Maica Alexandra nr. 30, sector 1, 011243 - București Mobil (0040) 724 08 35 09 E-mail [email protected] Website www.dianaculescu.ro Facebook https://www.facebook.com/dianaculescu.ro/ Naționalitate română Data nașterii 26 iulie 1976 Sex feminin Experiența profesională Perioada 2019-prezent Funcția sau postul ocupat Reglementator - Expert analiză și sistematizare legislație (Titlul IV - peisaj cultural) Activități și responsabilități principale Realizarea unei analize transversale a legislației cu incidență în domeniul peisajului cultural, consultarea autorităților și instituțiilor cu incidență în domeniu, organizarea de dezbateri profesionale, redactarea de rapoarte de analiză, implicare în procesul de sistematizare a legislației, de profil, participarea la elaborarea Codului Patrimoniului Cultural Numele și adresa angajatorului Ministerul Culturii și Identității Naționale Unitatea de Management a Proiectului, Bulevardul Unirii nr. 22, sector 3, București Perioada 2019-prezent Funcția sau postul ocupat Cadru didactic asociat Activități și responsabilități principale coordonarea atelierelor de proiectare și planificare peisageră pentru III Numele și adresa angajatorului Universitatea de Științe Agronomice și Medicină Veterinară București Specializarea PEISAGISTICĂ a Facultății de Horticultură B-dul Mărăști nr. 59, sector 1, 011464 - București Tipul activității sau sectorul de activitate Arhitectură Peisageră Perioada 2010-prezent Funcția -

The General Election in 20Th of May 1990 in the County of Constanța

RSP • No. 57 • 2018: 25-40 R S P ORIGINAL PAPER The General Election in 20th of May 1990 in the County of Constanța Marian Zidaru* Abstract: The first free election in Romania, after the coup d’état in 1989 represented a crucial moment in the Romanian history. The results of these first post communist free elections can not be analyses and explain without the presentation of the socio-economic and historical contextual which is specific both the forty five years of the communist dictatorship, and the five months of Post-Communism. The paper “The general election in 20th of May 1990 in the county of Constanta” which is my proposal for this conference contains a presentation in a chronological succession of the main events during the coup d’état in 22nd December 1989, and after the coup d’état till the election of may 20th 1990. I also included some juridical and political analysis and consideration about the election law system. On the basis of the documents from the personal archive of the honorable judge Dan Iulian Drăgan, a member of County Election Bureau, and his oral testimony, I succeded to have a clear image of the development of the 20th may 1990 election in the county of Constanta. Regarding the speculation of election fiddle, during the election, I can state that according to documents, there were some attempts, but the final result was not very much influenced. I also try to answer to the question why the electorate gave a massive vote to the National Salvation Front? Keywords: free election; County Election Bureau; Constanța; Romania * “Andrei Saguna” University Constanţa, Department of Social Science; Email: [email protected] 25 Marian ZIDARU The first free election in Romania, after the coup d’état in 1989 represented a crucial moment in the Romanian history. -

Roma As Alien Music and Identity of the Roma in Romania

Roma as Alien Music and Identity of the Roma in Romania A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Roderick Charles Lawford DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated, and the thesis has not been edited by a third party beyond what is permitted by Cardiff University’s Policy on the Use of Third Party Editors by Research Degree Students. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… ii To Sue Lawford and In Memory of Marion Ethel Lawford (1924-1977) and Charles Alfred Lawford (1925-2010) iii Table of Contents List of Figures vi List of Plates vii List of Tables ix Conventions x Acknowledgements xii Abstract xiii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 - Theory and Method -

Component 1. Elaboration of Bucharest's Iuds, Capital

ROMANIA Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program (P169577) COMPONENT 1. ELABORATION OF BUCHAREST’S IUDS, CAPITAL INVESTMENT PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT Output 3. Urban context and identification of key local issues and needs, and visions and objectives of IUDS and Identification of a long list of projects. Chapter 3. Spatial and Functional Profile March 2021 DISCLAIMER This report is a product of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/the World Bank. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. This report does not necessarily represent the position of the European Union or the Romanian Government. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable laws. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with the complete information to either: (i) the Municipality of Bucharest (Bd. Regina Elisabeta 47, Bucharest, Romania); or (ii) the World Bank Group Romania (Str. Vasile Lascăr 31, et. 6, Sector 2, Bucharest, Romania). This report was delivered in March 2021 under the Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program, concluded between the Municipality of Bucharest and the -

Efectele Parteneriatului Public-Privat În Serviciile Publice De Alimentare Cu Apă Şi De Canalizare Din Municipiul București (Perioada 2008-2012)

Ioan RADU, PhD Cleopatra ŞENDROIU, PhD THE EFFECTS OF THE PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP IN THE PUBLIC WATER SUPPLY AND SEWERAGE SERVICES OF BUCHAREST (2008 – 2012) 2013 FOREWORD This Study is a continuation of the one developed by a team of professors – researchers1 from the Academy of Economic Studies which measured the effects of the Public – Private Partnership in light of the changing perceptions of consumers in Bucharest between 2000 and 2007. The condition of the water supply and sewerage services in Bucharest at the end of 2007 was revealed most faithfully by the conclusions drawn after having processed the responses obtained in a survey conducted on a representative sample of customers of Apa Nova Bucharest about their perceptions on various aspects of the services at the end of 2007 compared to their perceptions prior to the concession. The main conclusion was that most consumers perceived a major and steady increase in both the quality of the water and sewerage services and the relationships of the supplier of these services with all consumers. This research is a continuation of the previous one and the authors have attempted a totally different vision from the first work to identify and 1 I. Radu, V. Lefter, C. Şendroiu, M. Ursăcescu, M. Cioc – Efectele parteneriatului public- privat în serviciile publice de alimentare cu apă şi de canalizare. Experienţa municipiului Bucureşti. ASE Publishing House, Bucharest, 2008. further quantify the positive or negative developments in the performance of Apa Nova Bucharest between 2008 and 2012 on the following levels: The degree of achievement by Apa Nova Bucharest of the objectives of the Concession Agreement. -

The Theory and Practice of Urban and Spatial Planning in Romania

S A J _ 2010 _ 2 _ original scientific article approval date 16 06 2010 UDK BROJEVI: 711.2(498) ID BROJ: 179336460 THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF URBAN AND SPATIAL PLANNING IN ROMANIA A B S T R A C T Different theoreticians place urbanism among sciences, arts, activities, or regulations, also accounting for its final product. The methods of urbanism include strategic planning, urban compositions, participative, managerial, and communication urbanism. All these conceptual and methodological sides are found in the Romanian approach to urbanism, making it representative as a case study. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to analyze the theoretical and practical approaches to urban and spatial planning in Romania from a historical perspective. The conclusions of the analysis indicate that territorial planning in Romania has two levels – urbanism and spatial planning, both resulting into urban/spatial planning documents. The elaboration and approval of these documents is subject to numerous laws changing rapidly, controlled by local and central authorities, and involves a long and complicated bureaucratic process. The accession of Romania to the European Union determined changes of this process, as well as a set of changes in the education system preparing the future professionals. The relevance of the results could be extended to formerly communist countries joining the European Union. Alexandru-Ionuţ Petrişor 139 KEY WORDS Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism - Faculty of Urbanism URBANISM SPATIAL PLANNING TERRITORIAL DEVELOPMENT ROMANIA S A J _ 2010 _ 2 _ INTRODUCTION: DEFINING THE URBANISM According to the principles of classic logics, a definition must first place its object in an already established class, and then expose the features that differentiate it from the others members of the class. -

Autobuze.Pdf

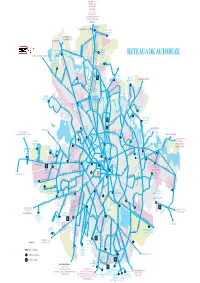

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 261 BANEASA RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE 204 205 304 Sisesti 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 112 205 261 COMPLEX 131 261301 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti COMERCIAL CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucu Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 COLOSSEUM 203 335 361 605 780 783 Bd.R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 112 Aerogarii R402 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 restii Noi DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 331 R436 CFR 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 112 135 243 Str. Jiului Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Sos. Chitilei 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Poligrafiei 231 243 Str. Peris 780 783 331 PIATA Str.Oi 243 382 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 243 382 R447PRESEI R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 243 131 203 205 261 304 135 343 105 203 231 tuz CARTIER 261 304 330 361 605 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 Bd. Marasti GIULESTI-SARBI 162 R441 R442 R443 r a lo c i s Bd. Expozitiei231 330 r o a dronache 162 163 105 780 R444 R446t e R409 243 343 Str. Sportului a r 105 i CLABUCET R447 o v l F 381 R448 A . -

Accessibility Study in Regard to Bucharest Underground Network

U.P.B. Sci. Bull., Series D, Vol. 73, Iss. 1, 2011 ISSN 1454-2358 ACCESSIBILITY STUDY IN REGARD TO BUCHAREST UNDERGROUND NETWORK Vasile DRAGU1, Cristina ŞTEFĂNICĂ2, Ştefan BURCIU3 Lucrarea îşi propune să identifice noi sensuri şi valenţe ale accesibilităţii pornind de la legătura dintre aceasta şi caracteristicile demografice ale zonelor servite de reţeaua de metrou. Prin studiul de caz realizat se caracterizează topologic reţeaua de metrou din Bucureşti şi se determină accesibilitatea nodurilor reţelei în vederea stabilirii măsurilor corespunzătoare de dezvoltare. În determinarea accesibilităţii au fost folosite exprimări originale care au condus la formularea de concluzii în ceea ce priveşte dezvoltarea reţelei, dar şi calitatea servirii locuitorilor de către metroul bucureştean. This paper tries to identify new meanings and aspects of accessibility starting from the correlations within and the demographical characteristics of the zones served by underground network. Through the case study herein, the underground network is topologically characterized and the nodes accessibility is determined for establishing the proper measures of development. The accessibility original approach led to conclusions regarding the network development and the quality of service offered to the inhabitants by the underground network. Key words: transport network, accessibility, topology 1. Introduction Connection of spatially separated points is the main purpose achieved by transportation assuring the possibility for individuals and communities to move and communicate, bringing coherence to certain zones development and to the relations among them [1]. Periodically, the city becomes scantier, validating the assumption that life has the property to extend, to invade and to assimilate new territories and environments. From local development centres, towns turned into high accessibility/attractiveness points – spatially connected through transport networks that catalyzed the continuous process of geographic spreading of activities [2,5]. -

EMERGENCY ORDINANCE No. 22 of February 4, 2020 on the General Agricultural Census in Romania Round 2020

EMERGENCY ORDINANCE no. 22 of February 4, 2020 on the general agricultural census in Romania round 2020 ISSUER: Government PUBLISHED IN: Official Gazette no. 105 of 12 February 2020 Effective date: February 12, 2020 Consolidated form valid on 24 August 2020 This consolidated form is valid starting with 22 August 2020, until 24 August 2020 ────────── *) CTCE note: Consolidated form of the EMERGENCY ORDINANCE no. 22 of February 4, 2020, published in the Official Gazette no. 105 of February 12, 2020, on August 22, 2020 is made by including the amendments and supplementations made by: LAW no. 177 of 18 August 2020. The contents of this act belong exclusively to S.C. Centrul Teritorial de Calcul Electronic S.A. Piatra-Neamţ and is not an official document, being intended to inform users. ────────── Having regard to Regulation (EU) 2018/1.091 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 July 2018 on integrated farm statistics and repealing Regulations (EC) No 1166/2008 and (EU) No 1337/2011, which provides in Article 5 that “Member States shall collect and provide the core structural data (‘core data’) related to the agricultural holdings referred to in Article 3(2) and (3), for the reference years 2020, 2023 and 2026, as listed in Annex III. The core data collection for the reference year 2020 shall be carried out as a census.”, Whereas the objective of the general agricultural census is to provide statistical data for the foundation and implementation of national and European agricultural policies, in accordance with the European Statistical System, necessary for the process of Romania's participation, as a Member State of the European Union, in the Common Agricultural Policy, data collection shall take place between 1 February 2021 and 30 April 2021 in all administrative-territorial units in Romania , for the following reference periods: agricultural year 2020, for variables regarding land and persons who worked in agriculture, calendar year 2020 for the management of manure, i.e.