Branding Burberry: Britishness, Heritage, Labour and Consumption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luxury Brands Expansion in China

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv Luxury brand’s expansion in China - Opportunities and possible strategies Bachelor thesis in International Business Spring 2011 Author: Dang, Xi-Er 890324-5085 Wan, Jessica 880226-4369 Tutor: Harald Dolles Acknowledgement This bachelor thesis has been written at the department International Business at the School of Business, Economics and Law at the University of Gothenburg. In the time frame of ten weeks, we have gained great knowledge about the luxury industry in general and luxury brands operating in China, in particular. Additionally, we have acquired a deeper understanding on how to conduct an academic research. We would like to thank our tutor Harald Dolles who has been of great help with assistance and guidance along the construction of our thesis. School of Business, Economics and Law, June 2011 ____________________________ ______________________________ Jessica Wan Xi-Er Dang 2 Abstract Since the economic reform of China in 1978, the country has been under a process of industrialization and modernization. The average household income has risen, where the proportion of middle-class households, earning more than RMB 3 500 per month, has increased. In addition, there is a great share of the „China elite‟, which consists of the upper middle-class and the very wealthy. Due to China‟s enormous market of 1.3 billion people and the growth of wealthier households, the country has become the largest market for luxury. Many luxury brands are established in the market today, some with a greater presence, others more limited. -

The Rights of War and Peace Book I

the rights of war and peace book i natural law and enlightenment classics Knud Haakonssen General Editor Hugo Grotius uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu ii ii ii iinatural law and iienlightenment classics ii ii ii ii ii iiThe Rights of ii iiWar and Peace ii iibook i ii ii iiHugo Grotius ii ii ii iiEdited and with an Introduction by iiRichard Tuck ii iiFrom the edition by Jean Barbeyrac ii ii iiMajor Legal and Political Works of Hugo Grotius ii ii ii ii ii ii iiliberty fund ii iiIndianapolis ii uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu This book is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as the design motif for our endpapers is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 b.c. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash. ᭧ 2005 Liberty Fund, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 c 54321 09 08 07 06 05 p 54321 Frontispiece: Portrait of Hugo de Groot by Michiel van Mierevelt, 1608; oil on panel; collection of Historical Museum Rotterdam, on loan from the Van der Mandele Stichting. Reproduced by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grotius, Hugo, 1583–1645. [De jure belli ac pacis libri tres. English] The rights of war and peace/Hugo Grotius; edited and with an introduction by Richard Tuck. p. cm.—(Natural law and enlightenment classics) “Major legal and political works of Hugo Grotius”—T.p., v. -

Parker Review

Ethnic Diversity Enriching Business Leadership An update report from The Parker Review Sir John Parker The Parker Review Committee 5 February 2020 Principal Sponsor Members of the Steering Committee Chair: Sir John Parker GBE, FREng Co-Chair: David Tyler Contents Members: Dr Doyin Atewologun Sanjay Bhandari Helen Mahy CBE Foreword by Sir John Parker 2 Sir Kenneth Olisa OBE Foreword by the Secretary of State 6 Trevor Phillips OBE Message from EY 8 Tom Shropshire Vision and Mission Statement 10 Yvonne Thompson CBE Professor Susan Vinnicombe CBE Current Profile of FTSE 350 Boards 14 Matthew Percival FRC/Cranfield Research on Ethnic Diversity Reporting 36 Arun Batra OBE Parker Review Recommendations 58 Bilal Raja Kirstie Wright Company Success Stories 62 Closing Word from Sir Jon Thompson 65 Observers Biographies 66 Sanu de Lima, Itiola Durojaiye, Katie Leinweber Appendix — The Directors’ Resource Toolkit 72 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy Thanks to our contributors during the year and to this report Oliver Cover Alex Diggins Neil Golborne Orla Pettigrew Sonam Patel Zaheer Ahmad MBE Rachel Sadka Simon Feeke Key advisors and contributors to this report: Simon Manterfield Dr Manjari Prashar Dr Fatima Tresh Latika Shah ® At the heart of our success lies the performance 2. Recognising the changes and growing talent of our many great companies, many of them listed pool of ethnically diverse candidates in our in the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250. There is no doubt home and overseas markets which will influence that one reason we have been able to punch recruitment patterns for years to come above our weight as a medium-sized country is the talent and inventiveness of our business leaders Whilst we have made great strides in bringing and our skilled people. -

Rurality, Class, Aspiration and the Emergence of the New Squirearchy

Rurality, Class, Aspiration and the Emergence of the New Squirearchy Jesse Heley Submission for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Geography & Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University 25th May 2008 For Ted, Sefton and the Wye Valley Contents 1 The coming of the New Squirearchy 1 1.1. The rebirth of rural Britain and the emergence of a New Squirearchy 2 1.2. Beyond the gravelled driveway 9 1.3. At play; beyond play? 15 1.4. From squirearchy to New Squirearchy; a reflection of changing class politics 25 1.5. Research goals 33 2 Class, identity and gentryfication 37 2.1. The New Squirearchy and the new middle class 37 2.2. A third way; through cultural capital to performing identity 43 2.3. Embodied rural geographies 48 2.4. Everyday performances and rural competencies 61 2.5. Tracking rural identity and accounting for experience 66 3 As I rode out … 75 3.1. Ethnography and rural geography 75 3.2. Eamesworth and the irony of a New Squirearchy 80 3.3. The coming of the commuter 84 3.4. On being a local lad 88 3.5. Gathering and interpreting evidence 91 3.6. The mechanics of data collection 94 3.7. The ethics of squire chasing 97 4 Out of the Alehouse 105 4.1. The pub, the squirearchy and the rural idyll 105 4.2. The Six Tuns 107 4.3. Office politics 110 4.4. Pass the port; the role of alcohol 113 4.5. Masculinity 115 4.6. New Squires; or archetypal middle class pub dwellers 119 4.7. -

Apple Strategy Teardown

Apple Strategy Teardown The maverick of personal computing is looking for its next big thing in spaces like healthcare, AR, and autonomous cars, all while keeping its lead in consumer hardware. With an uphill battle in AI, slowing growth in smartphones, and its fingers in so many pies, can Apple reinvent itself for a third time? In many ways, Apple remains a company made in the image of Steve Jobs: iconoclastic and fiercely product focused. But today, Apple is at a crossroads. Under CEO Tim Cook, Apple’s ability to seize on emerging technology raises many new questions. Primarily, what’s next for Apple? Looking for the next wave, Apple is clearly expanding into augmented reality and wearables with the Apple Watch AirPods wireless headphones. Though delayed, Apple’s HomePod speaker system is poised to expand Siri’s footprint into the home and serve as a competitor to Amazon’s blockbuster Echo device and accompanying virtual assistant Alexa. But the next “big one” — a success and growth driver on the scale of the iPhone — has not yet been determined. Will it be augmented reality, healthcare, wearables? Or something else entirely? Apple is famously secretive, and a cloud of hearsay and gossip surrounds the company’s every move. Apple is believed to be working on augmented reality headsets, connected car software, transformative healthcare devices and apps, as well as smart home tech, and new machine learning applications. We dug through Apple’s trove of patents, acquisitions, earnings calls, recent product releases, and organizational structure for concrete hints at how the company will approach its next self-reinvention. -

FTSE Factsheet

FTSE COMPANY REPORT Share price analysis relative to sector and index performance Data as at: 27 March 2020 Brand Architekts Group BAR Personal Goods — GBP 1.2 at close 27 March 2020 Absolute Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Sector Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Index PERFORMANCE 21-Apr-2015 1D WTD MTD YTD Absolute - - - - Rel.Sector - - - - Rel.Market - - - - VALUATION Data unavailable Trailing PE 8.1 EV/EBITDA 7.5 PB 1.1 PCF 3.8 Div Yield 3.9 Price/Sales 1.5 Net Debt/Equity 0.1 Div Payout 31.4 ROE 13.5 DESCRIPTION Data unavailable The principal activities of the is a market leader in the development, formulation, and supply of personal care and beauty products. See final page and http://www.londonstockexchange.com/prices-and-markets/stocks/services-stock/ftse-note.htm for further details. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Please see the final page for important legal disclosures. 1 of 4 FTSE COMPANY REPORT: Brand Architekts Group 27 March 2020 Valuation Metrics Price to Earnings (PE) EV to EBITDA Price to Book (PB) 28-Feb-2020 28-Feb-2020 28-Feb-2020 80 25 6 70 5 20 60 4 50 15 +1SD +1SD +1SD 40 3 10 Avg 30 Avg Avg 2 20 5 -1SD 1 -1SD 10 -1SD 0 0 0 Mar-2015 Mar-2016 Mar-2017 Mar-2018 Mar-2019 Mar-2015 Mar-2016 Mar-2017 Mar-2018 Mar-2019 Mar-2015 Mar-2016 Mar-2017 Mar-2018 Mar-2019 PZ Cussons 29.7 Watches of Switzerland Group 14.6 Watches of Switzerland Group 10.3 Burberry Group 20.0 Unilever 11.2 Unilever 8.7 Personal Goods 19.5 Personal Goods 11.1 Personal Goods 7.9 Unilever 19.1 Burberry Group 10.7 Burberry Group 4.7 Brand -

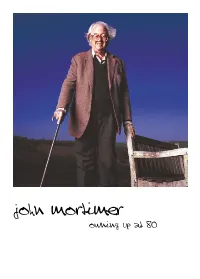

Imagine... John Mortimer

john mortimer owning up at 80 john mortimer owning up at 80 In the year he celebrates his 80th birthday, John Mortimer, the barrister turned author who became a household name with the creation of his popular drama Rumpole of the Bailey, is about to publish his latest book, Where There’s a Will. Imagine captures him pondering on life and offering advice to his children, grandchildren and in his own words “anyone who’ll listen”. John Mortimer’s wit and love of life shines through in this reflection on his life and career.The film eavesdrops on his 80th birthday celebrations, visits his childhood home – where he still lives today – and goes to his old law chambers.There are interviews with the people who know him best, including Richard Eyre, Jeremy Paxman, Kathy Lette, Leslie Phillips and Geoffrey Robertson QC. Imagine looks at the extraordinary influence Mortimer has had on the legal system in the UK.As a civil rights campaigner and defender par excellence in some of the most high-profile, inflammatory trials ever in the UK – such as the Oz trial and the Gay News case – he brought about fundamental changes at the heart of British law. His experience in the courts informs all of Mortimer’s writing, from plays, novels and articles to the infamous Rumpole of the Bailey, whose central character became a compelling mouthpiece for Mortimer’s liberal political views. Imagine looks at the great man of law, political campaigner, wit, gentleman, actor, ladies’ man and champagne socialist who captured the hearts of the British public.. -

Cafang a Palinak: ‘David’ Begins and Ends with Pangpar Phunkhat

316 Dd D, d /di:/ n (pl D’s, d’s /di:z/) 1 Mirang (English) daffodil /{dFfEdI/ n tawba nei aire pian ih parmi cafang a palinak: ‘David’ begins and ends with pangpar phunkhat. a ‘D’/D. 2 D (music) C major scale ih a panihnak. daft /dA:ft; US dFft/ adj (-er, -est) (infml) a aa-mi, 3 D cathiam hmat (a niam bik lam). fiim lo: Don’t’ be so daft! He’s gone a bit daft D abbr (US politics) Democrat; Democratic. Cf R (in the head), ie He has become slightly insane. 3. daftness n [U]. D (also d) symb Roman nambat 500. Cf D-DAY. dagger /{dFGER/ n 1 kaphnih hriam thunkawng D d abbr 1 (in former British currency) a hlaan ih naam. 2 canamtu ih hmanmi hminsinnak (†). British tangka penny; pennies or pence (Latin 3 (idm) at daggers drawn (with sb) rem lo, raal denarius; denarii): a 2d stamp 6d each. Cf P aw: She’s at daggers drawn with her colleagues. 2. 2 thi: Emily Jane Clifton d 1865. Cf B. He and his partner are at daggers drawn. look -d -ED. daggers at sb thinheng zetin mi zoh: He looked DA abbr 1 deposit account. 2 (US) District daggers at me when I told him to work harder. Cf Attorney. CLOAK-AND-DAGGER (CLOAK). dab1 /dFb/ v (-bb-) 1 [Tn] diim te’n nam: She dago /{deIGEU/ n (pl ~s) (? sl offensive) nautatnak dabbed her eyes (with a tissue). 2 [Ipr] ~ at sth ih hmanmi qong, ramdang mi – hmai dum nawn tuam fek (hmaa): She dabbed at the cut with pawl (Italian, Spaniard, lole, Portuguese.) cotton wool. -

1 Asdatown: the Intersections of Classed Places and Identities. Dr. B

Asdatown: The intersections of classed places and identities. Dr. B. Gidley and Dr. Alison Rooke Dept of Sociology Goldsmiths Introduction This chapter will explore the intersections between classed places and identities, focusing on the UK and examining the ways in which the figures of the ‘chav’ and the ‘pikey’ have been represented in British popular culture and in official policy discourses. We will argue that these representations conflate the racialized identity of the Gypsy Traveller with white working class identities and draw on the presence or proximity of Irish or Gypsy Travellers to the white ‘underclass’ in order to metonymically racialize the white working class as a whole. The politics of space, we will argue, is central to this process. Existing sociological and cultural geography literature hints at the active role of the spatial imaginary in classing people (Charleworth 2000, Robson 2000, Haylett 2000, Hewitt 2005, Skeggs 2005). We will argue that particular spaces and places – housing estates, and places described as ‘chav towns’ – are used discursively as a way of fixing people in racialized class positions. In British culture, there is a long history of reading poverty and class spatially. Indeed, the roots of British empirical sociology can be found in a middle class preoccupation with the poor working class others who could be located in districts of the city. While the persistence of poverty is explained in policy discourse in terms of ‘cycles’ and ‘cultures’ of poverty entrenched in a regressive or ‘backwards’ working 1 class, we will argue that what is regressive – and tainted by its Victorian imperialist history – is the persistent classing gaze which fixes working class people in place. -

The Aesthetics of Mainstream Androgyny

The Aesthetics of Mainstream Androgyny: A Feminist Analysis of a Fashion Trend Rosa Crepax Goldsmiths, University of London Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Sociology May 2016 1 I confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Rosa Crepax Acknowledgements I would like to thank Bev Skeggs for making me fall in love with sociology as an undergraduate student, for supervising my MA dissertation and encouraging me to pursue a PhD. For her illuminating guidance over the years, her infectious enthusiasm and the constant inspiration. Beckie Coleman for her ongoing intellectual and moral support, all the suggestions, advice and the many invaluable insights. Nirmal Puwar, my upgrade examiner, for the helpful feedback. All the women who participated in my fieldwork for their time, patience and interest. Francesca Mazzucchi for joining me during my fieldwork and helping me shape my methodology. Silvia Pezzati for always providing me with sunshine. Laura Martinelli for always being there when I needed, and Martina Galli, Laura Satta and Miriam Barbato for their friendship, despite the distance. My family, and, in particular, my mum for the support and the unpaid editorial services. And finally, Goldsmiths and everyone I met there for creating an engaging and stimulating environment. Thank you. Abstract Since 2010, androgyny has entered the mainstream to become one of the most widespread trends in Western fashion. Contemporary androgynous fashion is generally regarded as giving a new positive visibility to alternative identities, and signalling their wider acceptance. But what is its significance for our understanding of gender relations and living configurations of gender and sexuality? And how does it affect ordinary people's relationship with style in everyday life? Combining feminist theory and an aesthetics that contrasts Kantian notions of beauty to bridge matters of ideology and affect, my research investigates the sociological implications of this phenomenon. -

Meditative Story Transcript – Angela Ahrendts Click Here to Listen to The

Meditative Story Transcript – Angela Ahrendts Click here to listen to the full Meditative Story episode with Angela Ahrendts. ANGELA AHRENDTS: I stand mesmerized seeing this eagle soar and dive, soar and dive. At this moment it’s the strangest thing, an inner peace takes over me with each breath. I feel this sudden clarity, this deep confidence. An idea quickly builds inside of me: I am not a tree; I am not supposed to stay permanently fixed and rooted where I am. My three babies will fly the nest. They’ll be gone. The eagle is my sign in my storm. I am supposed to fly. ROAHN GUNATILLAKE: Angela Ahrendts is best known in the business world where as CEO of Burberry she turned the company around, and then stepped out of the number one position to help Apple reinvent its famous retail store environment. But the Meditative Story she shares today couldn’t be further from the high-flying worlds of fashion and technology – it’s about finding sanctuaries that we can turn to for clarity when new direction and new possibilities show up in our lives. In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat and Thrive Global, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide. The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world. AHRENDTS: With a blanket tucked beneath my arm, I head out into the backyard, basking in the warm afternoon light. -

Schedule of Responses to the Mcguinness Institute's OIA 2021/07

Schedule of responses to the McGuinness Institute’s OIA 2021/07: Update, Nation Dates, GDS Index, and OIA 2020/07 as at 6 April 2021 2. Department of Conservation 3. Department of Corrections 4. Department of Internal Affairs 5. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 6. Education Review Office 7. Government Communications Security Bureau 8. Inland Revenue Department 9. Land Information New Zealand 10. Oranga Tamariki – Ministry for Children 11. Ministry for Culture and Heritage 12. Ministry for Pacific Peoples 13. Ministry for Primary Industries 14. Ministry for the Environment 16. Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment 17. Ministry of Defence 18. Ministry of Education 19. Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade 20. Ministry of Health 21. Ministry of Housing and Urban Development 22. Ministry of Justice 23. Ministry of Māori Development 24. Ministry of Social Development 25. Ministry of Transport 26. New Zealand Customs Service 27. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service 28. Public service Commission 30. Statistics New Zealand 32. The Treasury 2. Department of Conservation 20210216 Our OIA 2021/07 OIAD-572 16 February 2021 Wendy McGuinness McGuinness Institute Te Hononga Waka By email: [email protected] Tēnā koe Wendy Thank you for your Official Information Act request (your reference 2021/07) to the Department of Conservation, received on 18 January 2021. Your questions and our responses are listed below: 1. Please list all GDSs that were archived in 2019/2020, being those that were in operation as at 31 December 2018 (see list attached) but are no longer in operation as at 31 December 2020? Please state the date (e.g., month and year) and the reason the strategy was archived.