Diseases Associated with Genomic Imprinting Jon F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigation of the Underlying Hub Genes and Molexular Pathogensis in Gastric Cancer by Integrated Bioinformatic Analyses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Investigation of the underlying hub genes and molexular pathogensis in gastric cancer by integrated bioinformatic analyses Basavaraj Vastrad1, Chanabasayya Vastrad*2 1. Department of Biochemistry, Basaveshwar College of Pharmacy, Gadag, Karnataka 582103, India. 2. Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001, Karanataka, India. * Chanabasayya Vastrad [email protected] Ph: +919480073398 Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001 , Karanataka, India bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract The high mortality rate of gastric cancer (GC) is in part due to the absence of initial disclosure of its biomarkers. The recognition of important genes associated in GC is therefore recommended to advance clinical prognosis, diagnosis and and treatment outcomes. The current investigation used the microarray dataset GSE113255 RNA seq data from the Gene Expression Omnibus database to diagnose differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Pathway and gene ontology enrichment analyses were performed, and a proteinprotein interaction network, modules, target genes - miRNA regulatory network and target genes - TF regulatory network were constructed and analyzed. Finally, validation of hub genes was performed. The 1008 DEGs identified consisted of 505 up regulated genes and 503 down regulated genes. -

Immune Proteins and Glutamatergic Dysfunction in Autism Lisa M

SHARED NEUROBIOLOGY OF AUTISM AND RELATED DISORDERS University of Southern California Los Angeles, California Young Investigator Program POSTER SESSION A Posters 1-8 Andrus Gerontology Center Monday June 11, 2007 1 Immune Proteins and Glutamatergic Dysfunction in Autism Lisa M. Boulanger Division of Biological Sciences, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA 92093 Autism is a complex neurological syndrome that is thought to result from a combination of environmental and genetic factors that impact brain development and function. One consistent finding in autism that may affect both brain development and function is an imbalance in glutamatergic neurotransmission (Lam et al., 2006). Genetic studies have found a significant link between autism and genes encoding certain isoforms of ionotropic glutamate receptors (GluRs) (e.g., NMDA, AMPA and kainate receptors; Jamain et al., 2002; Ramanathan et al., 2004; Barnby et al., 2005), and modifications in the levels of specific AMPA receptor subunits have been observed in the cerebellum of patients with autism (Purcell et al., 2001). Alterations in GluRs have also been reported in related disorders, including Rett syndrome (Blue et al., 1999) and tuberous sclerosis (White et al., 2001). However, the molecular and cellular causes of these changes remain elusive. In parallel, many studies have identified a link between autism and abnormalities in immune genes and/or immune function (Cohly and Panja, 2005). One emerging hypothesis is that infection or other immune challenge, in a genetically predisposed individual, may contribute to the pathogenesis of autism. In support of this hypothesis, maternal infection is a risk factor for autism in humans, and mouse models of maternal immune challenge support a role for the immune response – specifically upregulation of cytokines--in the origins of autism (Patterson, 2002; Shi et al., 2003; Molloy et al., 2006). -

Identification of Genomic Biomarkers for Improving Risk Stratification of Low

Identification of Genomic Biomarkers for Improving Risk Stratification of Low- and Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer Patients By Walead Ebrahimizadeh Faculty of Medicine, Division of Experimental Surgery McGill University, Montreal August 2019 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Ph.D. © Walead Ebrahimizadeh 2019 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................... I List of Tables .............................................................................................................................................. IV List of Figures .............................................................................................................................................. V ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................................ VI RÉSUMÉ .................................................................................................................................................. VII ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................................................... VIII CONTRIBUTION TO ORIGINAL KNOWLEDGE.................................................................................. IX CONTRIBUTION OF AUTHORS .......................................................................................................... -

WO 2015/048577 A2 April 2015 (02.04.2015) W P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2015/048577 A2 April 2015 (02.04.2015) W P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 48/00 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/US20 14/057905 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 26 September 2014 (26.09.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (25) Filing Language: English PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, (26) Publication Language: English SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: 61/883,925 27 September 2013 (27.09.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 61/898,043 31 October 2013 (3 1. 10.2013) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, (71) Applicant: EDITAS MEDICINE, INC. -

Epigenetic Regulation of Processes Related to High Level of Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 in Obese Subjects

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Epigenetic Regulation of Processes Related to High Level of Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 in Obese Subjects Teresa Płatek 1,*, Anna Polus 1, Joanna Góralska 1, Urszula Ra´zny 1 , Agnieszka Dziewo ´nska 1, Agnieszka Micek 2 , Aldona Dembi ´nska-Kie´c 1, Bogdan Solnica 1 and Małgorzata Malczewska-Malec 1 1 Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Jagiellonian University Medical College, 15a Kopernika Street, 31-501 Krakow, Poland; [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (J.G.); [email protected] (U.R.); [email protected] (A.D.); [email protected] (A.D.-K.); [email protected] (B.S.); [email protected] (M.M.-M.) 2 Department of Nursing Management and Epidemiology Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Jagiellonian University Medical College, 25 Kopernika Street, 31-501 Krakow, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-12-424-87-87 Abstract: We hypothesised that epigenetics may play an important role in mediating fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) resistance in obesity. We aimed to evaluate DNA methylation changes and miRNA pattern in obese subjects associated with high serum FGF21 levels. The study included 136 participants with BMI 27–45 kg/m2. Fasting FGF21, glucose, insulin, GIP, lipids, adipokines, miokines and cytokines were measured and compared in high serum FGF21 (n = 68) group to low Citation: Płatek, T.; Polus, A.; FGF21 (n = 68) group. Human DNA Methylation Microarrays were analysed in leukocytes from Góralska, J.; Ra´zny, U.; each group (n = 16). -

Translational Profiling Reveals the Transcriptome of Leptin Receptor Neurons and Its Regulation by Leptin

TRANSLATIONAL PROFILING REVEALS THE TRANSCRIPTOME OF LEPTIN RECEPTOR NEURONS AND ITS REGULATION BY LEPTIN by Margaret B. Allison A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Molecular and Integrative Physiology) In the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Martin G. Myers Jr., Chair Associate Professor Carol F. Elias Professor Malcolm J. Low Professor Suzanne Moenter Professor Audrey Seasholtz Before you leave these portals To meet less fortunate mortals There's just one final message I would give to you: You all have learned reliance On the sacred teachings of science So I hope, through life, you never will decline In spite of philistine defiance To do what all good scientists do: Experiment! -- Cole Porter There is no cure for curiosity. -- unknown © Margaret Brewster Allison 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a research university to raise a graduate student. There are many people who have supported me over the past six years at Michigan, and it is hard to imagine pursuing my PhD without them. First and foremost among all the people I need to thank is my mentor, Martin. Nothing I might say here would ever suffice to cover the depth and breadth of my gratitude to him. Without his patience, his insight, and his at times insufferably positive outlook, I don’t know where I would be today. Martin supported my intellectual curiosity, honed my scientific inquiry, and allowed me to do some really fun research in his lab. It was a privilege and a pleasure to work for him and with him. -

Original Article Unclassified Renal Cell Carcinoma: a Clinicopathological, Comparative Genomic Hybridization, and Whole-Genome Exon Sequencing Study

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7(7):3865-3875 www.ijcep.com /ISSN:1936-2625/IJCEP0000596 Original Article Unclassified renal cell carcinoma: a clinicopathological, comparative genomic hybridization, and whole-genome exon sequencing study Zhen-Yan Hu1*, Li-Juan Pang1*, Yan Qi1,2, Xue-Ling Kang1, Jian-Ming Hu1,2, Lianghai Wang1, Kun-Peng Liu1, Yuan Ren1, Mei Cui1, Li-Li Song1, Hong-An Li1, Hong Zou1,2, Feng Li1 1Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Shihezi University, Key Laboratory of Xinjiang Endemic and Ethnic Diseases, Ministry of Education of China, Xinjiang 832002, China; 2Tongji Hospital Cancer Center, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China. *Equal contributors. Received April 22, 2014; Accepted June 2, 2014; Epub June 15, 2014; Published July 1, 2014 Abstract: Unclassified renal cell carcinoma (URCC) is a rare variant of RCC, accounting for only 3-5% of all cases. Studies on the molecular genetics of URCC are limited, and hence, we report on 2 cases of URCC analyzed us- ing comparative genome hybridization (CGH) and the genome-wide human exon GeneChip technique to identify the genomic alterations of URCC. Both URCC patients (mean age, 72 years) presented at an advanced stage and died within 30 months post-surgery. Histologically, the URCCs were composed of undifferentiated, multinucleated, giant cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. Immunostaining revealed that both URCC cases had strong p53 protein expression and partial expression of cluster of differentiation-10 and cytokeratin. The CGH profiles showed chro- mosomal imbalances in both URCC cases: gains were observed in chromosomes 1p11-12, 1q12-13, 2q20-23, 3q22-23, 8p12, and 16q11-15, whereas losses were detected on chromosomes 1q22-23, 3p12-22, 5p30-ter, 6p, 11q, 16q18-22, 17p12-14, and 20p. -

Autocrine IFN Signaling Inducing Profibrotic Fibroblast Responses By

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 23, 2021 Inducing is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology , 11 of which you can access for free at: 2013; 191:2956-2966; Prepublished online 16 from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication August 2013; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300376 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/191/6/2956 A Synthetic TLR3 Ligand Mitigates Profibrotic Fibroblast Responses by Autocrine IFN Signaling Feng Fang, Kohtaro Ooka, Xiaoyong Sun, Ruchi Shah, Swati Bhattacharyya, Jun Wei and John Varga J Immunol cites 49 articles Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://jimmunol.org/subscription Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2013/08/20/jimmunol.130037 6.DC1 This article http://www.jimmunol.org/content/191/6/2956.full#ref-list-1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* Why • • • Material References Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2013 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 23, 2021. The Journal of Immunology A Synthetic TLR3 Ligand Mitigates Profibrotic Fibroblast Responses by Inducing Autocrine IFN Signaling Feng Fang,* Kohtaro Ooka,* Xiaoyong Sun,† Ruchi Shah,* Swati Bhattacharyya,* Jun Wei,* and John Varga* Activation of TLR3 by exogenous microbial ligands or endogenous injury-associated ligands leads to production of type I IFN. -

Supplemental Figures 04 12 2017

Jung et al. 1 SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES 2 3 Supplemental Figure 1. Clinical relevance of natural product methyltransferases (NPMTs) in brain disorders. (A) 4 Table summarizing characteristics of 11 NPMTs using data derived from the TCGA GBM and Rembrandt datasets for 5 relative expression levels and survival. In addition, published studies of the 11 NPMTs are summarized. (B) The 1 Jung et al. 6 expression levels of 10 NPMTs in glioblastoma versus non‐tumor brain are displayed in a heatmap, ranked by 7 significance and expression levels. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. 8 2 Jung et al. 9 10 Supplemental Figure 2. Anatomical distribution of methyltransferase and metabolic signatures within 11 glioblastomas. The Ivy GAP dataset was downloaded and interrogated by histological structure for NNMT, NAMPT, 12 DNMT mRNA expression and selected gene expression signatures. The results are displayed on a heatmap. The 13 sample size of each histological region as indicated on the figure. 14 3 Jung et al. 15 16 Supplemental Figure 3. Altered expression of nicotinamide and nicotinate metabolism‐related enzymes in 17 glioblastoma. (A) Heatmap (fold change of expression) of whole 25 enzymes in the KEGG nicotinate and 18 nicotinamide metabolism gene set were analyzed in indicated glioblastoma expression datasets with Oncomine. 4 Jung et al. 19 Color bar intensity indicates percentile of fold change in glioblastoma relative to normal brain. (B) Nicotinamide and 20 nicotinate and methionine salvage pathways are displayed with the relative expression levels in glioblastoma 21 specimens in the TCGA GBM dataset indicated. 22 5 Jung et al. 23 24 Supplementary Figure 4. -

1101 Master Table for Website

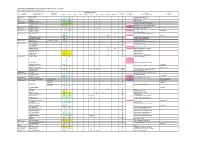

Imprinted transcriptional units in human and mouse - Jan 2011 Please advise regarding errors and omissions Location Transcriptional unit Functional Imprinting status Expressed ICR Protein RNAb Human (Mouse) Human (Mouse) component Human Mouse Primate Rat Rabbit Cow Pig Sheep Marsupial Monotreme allele methylation Name or description Description 1p36 (4 E2) TP73 (Trp73) I NR M Tumour related protein 1p32 EPS15 mono NR EGFR pathway substrate 15 1p31 DIRAS3 PD NO I P Ras homolog 2p12 (6 C3) LRRTM1 (Lrrtm1) I NR P leucine rich repeat transmembrane 2p15 (11 A3) COMMD1 (Commd1) NI I NI M Copper metabolism gene Murr1 (Zrsr1) NO I P M U2 small nuclear RNP auxiliary factor 4q22.1 (6 C1) NAP1L5 (Nap1l5) I I I P M Nucleosome assembly protein 6p11 (1 B) PRIM2 (Prim2) I NR PD M Primase, polypeptide 2 6q24 (10 A1) HYMAI (Hymai) I PD P M misc RNA PLAGL1 (Plagl1) I I I P Zinc finger protein 6q25 (17 A1) IGF2R (Igf2r) PI I I I I I I NI M Insulin-like growth factor receptor 2 (Air) NO I NO P M Igf2r AS SLC22A2 (Slc22a2) PI I M Organic cation transporter SLC22A3 (Slc22a3) PD I M Organic cation transporter 7p12 (11 A1) DDC (Ddc) Exon1a transcript NR I P Dopa decarboxylase GRB10 (Grb10) I I I M(P)c M Growth factor receptor-bound protein 7q21.3 (6 A1) CALCR (Calcr) I I M Calcitonin receptor TFPI2 (Tfpi2) I I M SGCE (Sgce) I I I NI P Sarcoglycan, epsilon PEG10 (Peg10) I I I I I NO P M Retroviral gag pol homologue PPP1R9A (Ppp1r9a) I I NI M Protein phosphatase inhibitor PON3 (Pon3) NI I M Paraoxonase 3 PON2 (Pon2) NI I M Paraoxonase 2 ASB4 (Asb4) NI I NI(PD) -

Autocrine IFN Signaling Inducing Profibrotic Fibroblast Responses by a Synthetic TLR3 Ligand Mitigates

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Inducing is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology published online 16 August 2013 from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication http://www.jimmunol.org/content/early/2013/08/16/jimmun ol.1300376 A Synthetic TLR3 Ligand Mitigates Profibrotic Fibroblast Responses by Autocrine IFN Signaling Feng Fang, Kohtaro Ooka, Xiaoyong Sun, Ruchi Shah, Swati Bhattacharyya, Jun Wei and John Varga J Immunol Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by http://jimmunol.org/subscription Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2013/08/20/jimmunol.130037 6.DC1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* Why • • • Material Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2013 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 28, 2021. Published August 16, 2013, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1300376 The Journal of Immunology A Synthetic TLR3 Ligand Mitigates Profibrotic Fibroblast Responses by Inducing Autocrine IFN Signaling Feng Fang,* Kohtaro Ooka,* Xiaoyong Sun,† Ruchi Shah,* Swati Bhattacharyya,* Jun Wei,* and John Varga* Activation of TLR3 by exogenous microbial ligands or endogenous injury-associated ligands leads to production of type I IFN. -

Rapid Isolation of Glomeruli Coupled with Gene Expression Profiling Identifies Downstream Targets in Pod1 Knockout Mice

Rapid Isolation of Glomeruli Coupled with Gene Expression Profiling Identifies Downstream Targets in Pod1 Knockout Mice Shiying Cui,* Chengjin Li,* Masatsugu Ema,† Jordan Weinstein,‡ and Susan E. Quaggin*‡ *The Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; †Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Division of Developmental Technology, Laboratory Animal Resource Center, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan; and ‡Division of Nephrology, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Mouse mutations have provided tremendous insights into the molecular basis of renal and glomerular development. However, genes often play important roles during multiple stages of nephrogenesis, making it difficult to determine the role of a gene in a specific cell lineage such as the podocyte. Conditional gene targeting and chimeric analysis are two possible approaches to dissect the function of genes in specific cell populations. However, these are labor-intensive and costly and require the generation, validation, and analysis of additional transgenic lines. For overcoming these shortcomings and, specifically, for studying the role of gene function in developing glomeruli, a technique to isolate and purify glomeruli from murine embryos was developed. Combined with gene expression profiling, this method was used to identify differentially expressed genes in glomeruli from Pod1 knockout (KO) mice that die in the perinatal period with multiple renal defects. Glomeruli from early developing stages (late S-shape/early capillary loop) onward can be isolated successfully from wild-type and KO kidneys at 18.5 d postcoitus, and RNA can readily be obtained and used for genome-wide microarray analysis. With this approach, 3986 genes that are differently expressed between glomeruli from Pod1 KO and wild-type mice were identified, including a four-fold reduction of ␣ 8 integrin mRNA in glomeruli from Pod1 KO mice that was confirmed by immunostaining.